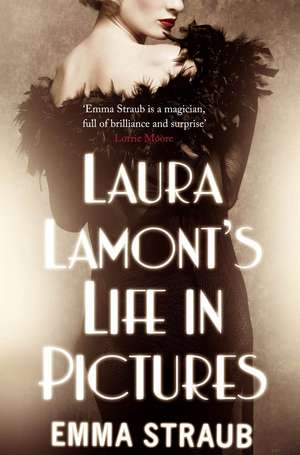

LAURA LAMONT'S LIFE IN PICTURES

Autor Emma Strauben Limba Engleză Paperback – 24 apr 2013

Preț: 36.44 lei

Preț vechi: 51.74 lei

-30% Nou

Puncte Express: 55

Preț estimativ în valută:

6.97€ • 7.25$ • 5.84£

6.97€ • 7.25$ • 5.84£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781447203209

ISBN-10: 1447203208

Pagini: 320

Dimensiuni: 128 x 195 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Ediția:Main Market Ed.

Editura: MacMillan

ISBN-10: 1447203208

Pagini: 320

Dimensiuni: 128 x 195 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Ediția:Main Market Ed.

Editura: MacMillan

Recenzii

"At once iconic and specific, Emma Straub's beautifully observed first novel explores the fraught trajectory of what has become a staple of the American dream: the hunger for stardom and fame. Laura Lamont’s Life in Pictures affords an intimate, epic view of how that dream ricochets through one American life." ߝ Jennifer Egan, author of A Visit from the Goon Squad

"Emma Straub is a magician, full of brilliance and surprise."— Lorrie Moore

"An exquisite debut novel that brings Depression-era Hollywood to life with startling immediacy. Laura Lamont is a memorable character, and Emma Straub illuminates her inner life with uncanny authority."— Tom Perrotta, author of The Leftovers and Little Children

“I absolutely loved this tale of one woman's incredible journey from small town girl to movie star. Straub brings Old Hollywood fully to life, in all its glamour, excess, ruthlessness, and beauty. I didn't want this marvelous novel to end.”— J. Courtney Sullivan, author of Commencement and Maine

“Fantastic…a stunningly intimate portrayal of one woman's life.”—Entertainment Weekly

“Straub’s brisk pacing and emotionally complex characters keep the story fresh…This bewitching novel is ultimately a celebration of those moments when we drop the act and play the hardest role of all: ourselves.”—O, The Oprah Magazine

“[A] timeless tale with true heartfelt warmth throughout…one of the most entertaining novels this fall.”—Matchbook Magazine

“delightful… mesmerizing.”—The Miami Herald

“at once a delicious depiction of Hollywood’s golden age and a sweet, fulfilling story about one woman’s journey through fame, love, and loss.”—Boston Globe

“Straub makes masterful use of the golden age of Hollywood to tap contemporary questions about the price of celebrity and a working mother’s struggle to balance all that matters.”—People

“Straub vividly recaptures the glamour and meticulously contrived mythology of the studio-system era.”—USA Today

“big-hearted…a witty examination of the psychic costs of reinvention in Hollywood’s golden age.”—The Washington Post

“[With] effortless prose and precise observations…Straub's novel explores themes of identity, career and motherhood through the filter of one woman's life experience…an entertaining narrative.”-San Francisco Chronicle

“Laura Lamont might be the most anticipated debut of the year. It's easy to understand the hullabaloo; Straub's style is clear and engaging, and her plot balances the glamour of the Hollywood Golden Age with trenchant thematic links to issues of contemporary working women. The result is a delightful, entertaining read with substance.”—Minneapolis Star Tribune

“Like the protagonist in her new novel, Laura Lamont’s Life in Pictures, Emma Straub is a rising star.”—TimeOut Chicago

“Will appeal to any girl who has left a small town behind to follow her dreams to the big city.”—Marie Claire

“Dramatic, human and historical: like a classic Hollywood movie…Straub knows when to linger and when to be brief, and her portrayal of Elsa/Laura’s relationships is exquisite…Peppered with stunningly crafted sentences and heart-twisting storytelling, the richness of this full life is portrayed with perceptive clarity.”—BUST Magazine

“Straub imbues her writing with surprising insights and wit… [her] writing reminds the reader how good literary fiction can precisely capture the human experience.”—Pop Matters

"Emma Straub is a magician, full of brilliance and surprise."— Lorrie Moore

"An exquisite debut novel that brings Depression-era Hollywood to life with startling immediacy. Laura Lamont is a memorable character, and Emma Straub illuminates her inner life with uncanny authority."— Tom Perrotta, author of The Leftovers and Little Children

“I absolutely loved this tale of one woman's incredible journey from small town girl to movie star. Straub brings Old Hollywood fully to life, in all its glamour, excess, ruthlessness, and beauty. I didn't want this marvelous novel to end.”— J. Courtney Sullivan, author of Commencement and Maine

“Fantastic…a stunningly intimate portrayal of one woman's life.”—Entertainment Weekly

“Straub’s brisk pacing and emotionally complex characters keep the story fresh…This bewitching novel is ultimately a celebration of those moments when we drop the act and play the hardest role of all: ourselves.”—O, The Oprah Magazine

“[A] timeless tale with true heartfelt warmth throughout…one of the most entertaining novels this fall.”—Matchbook Magazine

“delightful… mesmerizing.”—The Miami Herald

“at once a delicious depiction of Hollywood’s golden age and a sweet, fulfilling story about one woman’s journey through fame, love, and loss.”—Boston Globe

“Straub makes masterful use of the golden age of Hollywood to tap contemporary questions about the price of celebrity and a working mother’s struggle to balance all that matters.”—People

“Straub vividly recaptures the glamour and meticulously contrived mythology of the studio-system era.”—USA Today

“big-hearted…a witty examination of the psychic costs of reinvention in Hollywood’s golden age.”—The Washington Post

“[With] effortless prose and precise observations…Straub's novel explores themes of identity, career and motherhood through the filter of one woman's life experience…an entertaining narrative.”-San Francisco Chronicle

“Laura Lamont might be the most anticipated debut of the year. It's easy to understand the hullabaloo; Straub's style is clear and engaging, and her plot balances the glamour of the Hollywood Golden Age with trenchant thematic links to issues of contemporary working women. The result is a delightful, entertaining read with substance.”—Minneapolis Star Tribune

“Like the protagonist in her new novel, Laura Lamont’s Life in Pictures, Emma Straub is a rising star.”—TimeOut Chicago

“Will appeal to any girl who has left a small town behind to follow her dreams to the big city.”—Marie Claire

“Dramatic, human and historical: like a classic Hollywood movie…Straub knows when to linger and when to be brief, and her portrayal of Elsa/Laura’s relationships is exquisite…Peppered with stunningly crafted sentences and heart-twisting storytelling, the richness of this full life is portrayed with perceptive clarity.”—BUST Magazine

“Straub imbues her writing with surprising insights and wit… [her] writing reminds the reader how good literary fiction can precisely capture the human experience.”—Pop Matters

Notă biografică

Emma Straub is from New York City. She is the author of the short story collection Other People We Married. Her fiction and non-fiction have been published in Vogue, Tin House, The New York Times, andThe Paris Review Daily, and she is a staff writer for Rookie. Straub lives with her husband in Brooklyn, where she also works as a bookseller.

Extras

THE NURSEMAID

Fall 1941

The studio lawyers made everything easy: Within two years of her initial contract, Elsa was divorced and Laura had never been married. Gardner Brothers represented both Laura and Gordon, though it was easy to see whom the bosses favored. Who was Gordon but a sidekick, a bit player? Louis Gardner arranged to help Laura ?nd a bigger house, perfect for her and the two girls and one nanny. It was so easy to change a name: Clara and Florence became Emersons, as they should have been from the start. Elsa couldn’t believe she’d ever let herself or her daughters carry the name Pitts. The lawyers never charged Laura for their time: It was all in the contract. No one in the papers asked the questions Laura thought they might: If you’ve never been married, where did these two girls come from, the stork? Questions that did not follow the script were simply not allowed. The divorce had been Elsa’s idea, which was to say it had been Laura’s idea too. She found that there were certain activities (feeding the children, taking a shower) that she always did as Elsa, and others (going to dance class, speaking to Irving and Louis) that

she did as Laura, as though there were a switch in the middle of her back. The problem had been that neither Elsa nor Laura wanted to be married to Gordon, who wanted to be married only to Elsa. Before the girls were born, Gordon seemed happy enough for Elsa to be an actress, but not when she was the mother of his children.

Clara spent her days in the on-set school with all the other kids, though Florence was only a baby and stayed home with Harriet, the nanny, who was the ?rst black woman Laura had ever really known and charged as much per week as the lead actors at the Cherry County Playhouse. Harriet was exactly Laura’s age and had a kind, easy way with all three of the Emerson girls. The new house was on the other side of Los Feliz Boulevard, on a street that snaked up into the hills. Sycamore trees hung low over the sidewalks, and Laura loved to take long walks with Harriet and the girls, pointing out squirrels and even the occasional opossum. Grif?th Park wasn’t technically Laura’s backyard, but that was how she liked to think of it. She went to every concert she could at the Greek Theatre and at the Hollywood Bowl, which wasn’t often but often enough, and far more often than if she had stayed in Door County, Wisconsin. She sat outside, under the stars, with all of Los Angeles hushed and quiet behind her; Laura felt that she was once again sitting in the patch of grass outside the Cherry County Playhouse, and every note was sung just for her. One evening, a secretary found Laura on her way from the day care to dance class, and stopped her in her tracks. Irving Green had a box at the Hollywood Bowl, and wanted Laura to be his date for the evening. It was never clear how Irving came to possess all the pieces of information he did, just that he was very good at ?nding things out and holding them all inside his brain until he needed them. Laura said yes, which neither pleased nor surprised the secretary, and Harriet stayed home with the girls. Irving and his driver came to pick her up at six, before dusk, and they sat in near silence until they reached their destination, which gave Laura ample time to examine the inside of the automobile, which was the ?rst Rolls-Royce she’d ever seen up close. When they arrived at the Hollywood Bowl, ushers quickly showed them to their seats, which were inches from the stage, so close that Laura could have reached out and grabbed the ? rst violinist’s bow if she’d had the urge. A few minutes in, an usher hurried over to Irving’s side, whispered in his ear, and they ducked out again. Laura fussed nervously, sure that everyone in Los Angeles was staring straight at her, wondering why she’d been chosen as his date at all, and sure that he probably wasn’t coming back. When Irving returned a few minutes later, he said only, “Garbo,” as if that were all that was necessary, and it was.

“I’ve been meaning to ask you,” Laura said, in between movements. The seats around them were empty; the Bowl wasn’t always full, she knew from her time in the cheap seats several hundred feet from where they were sitting, but even so, Laura imagined that Irving was behind their seclusion, that he held unseen power here as on the lot. “Why ‘Brothers,’ when it’s only Louis? Isn’t that misleading?” She blushed at her wrong choice of words—she hadn’t meant misleading, which implied that Louis, their boss and Irving’s mentor, was hoodwinking the audiences. She’d meant secretive, or goofy, even, something that she hadn’t communicated. Laura was nervous whenever she was alone with Irving, whether it was in his of?ce or the few times she’d seen him walking purposefully around the lot. There were things everyone on the lot knew about Irving, things Laura had overheard: He’d been sick as a child, and there was something wrong still, a weakness in a ventricle (so said Edna, the costume assistant) or a lung (so said Peggy, a devoted gossip). Laura didn’t think she’d ever be bold enough to ?nd out the truth. Eating together was the worst: Irving hardly touched his food, swallowing tinier bites than Laura knew was possible and pronouncing himself stuffed. The desire for him to like her was so strong she could barely think. Laura thought of the ?rst time they’d met, and how silly she’d found all those actors pretending to examine their shoes when all they really wanted was his attention. Now she was just as guilty. He was a father ?gure to all of them, and most of the actors weren’t afraid to get scrappy with their siblings.

“Oh,” Irving said, “that. I told Louis I thought it sounded better.”

The orchestra began playing a selection from Così fan Tutte. Strings soared up into the sky, and Laura felt as if the entire park were ?lled with bubbles. She laughed and turned her head toward the sky, as if the stars would laugh back at her.

“That’s rich,” Laura said. “That’s rich.”

Irving reached over and put her hand in his, never turning his eyes away from the stage. His skin was soft and not nearly as cold as she imagined it would be, and even though Laura’s hand began to perspire, Irving didn’t pull away. Laura knew that from the cheap seats, the Hollywoodland sign was visible on the hills behind the dome of the Bowl, and she felt it there, ?ashing in the darkness like an electric eel. They sat quietly for the rest of the concert, ostensibly listening to the music, though Laura could hear nothing except the sound of her own heart beating wildly within her chest. Garbo may have been on the phone, but Laura was there, right there, sitting beside him, feeling the bones in Irving’s surprisingly strong grip.

The ?rst starring role Irving gave to Laura was in a ?lm with Ginger, Kissing Cousins—they played sisters, which made them both squeal with excitement. Laura was blond and Ginger was red, which meant that Ginger was the saucy one, and Laura was the innocent. The sisters were from Iowa and had moved to Los Angeles to be stars. It was a simple story, with lots of ?irting and costume changes. Laura’s favorite scene involved the girls dancing clumsily around a café, threatening to poke the other patrons’ eyes out with their parasols. She loved being in front of the camera, loved the weight of the thick crinolines under her dress, loved the elaborate hats made of straw and feathers. Acting in an honest-to-goodness motion picture was the ?rst thing Laura had done that made her think of Hildy without feeling like she’d been socked in the jaw—Hildy would have loved every inch of ?lm she’d shot, every dip and twirl, and that made Laura feel like she would have done it all for free. Of course she would have! Every actor and actress on the lot would have worked for free; that was the truth. Gardner Brothers didn’t know the depth of desire that was on its acres, not the half of it.

There were differences between acting onstage and on-screen; Laura felt the gulf at once. At the playhouse, choices were made on a nightly basis, always prompted by the feelings in the air, by the choices made by the actors around you. There were slight variations, almost imperceptible, sometimes caused by a tickle in your throat or a giant lightning bug zipping across the stage. On ?lm, choices were made over and over again, a dozen times in a row, from this angle and that, with close-ups and long shots and cranes overhead. The movements were smaller, the voice lower. Laura beamed too widely, sang too loudly. Everything had to be brought down, and done on an endless loop. She and Ginger skipped in circles for hours, it seemed, their hoop skirts knocking against each other like soft, quick-moving clouds hurrying across the sky.

Kissing Cousins was a modest hit, and though the critics called it “a lesser entry into the Johnny and Susie canon, though without the star power those two pint-sized powerhouses might have lent,” moviegoers responded to Laura’s sweetness on-screen. She got fan mail at the studio: whole bags of letters from teenage girls who wanted to know how she got her hair to do that, what color lipstick she liked best. One boy wrote and asked her to marry him. She kept that one; the rest she passed along to the secretaries at the studio, one of whom was now devoted just to her and Ginger, the new girls in town. Irving and Louis had her pose for photos—a white silk dress, gardenias in her hair—that could be signed and sent out to her fans. The dress was the most expensive thing Laura had ever felt against her skin, and she wore it for as long as possible before Edna asked for it back. Laura had fans: a small but growing number. Irving Green and all the imaginary Gardner Brothers brothers made sure of it.

On top of the dance classes (Guy, chastened by the girls’ newfound success, left them alone in the back of the class, and they did improve, slowly, at both the ronds de jambe and the poker faces necessary to survive the class period), Laura and Ginger were now required to shave their legs on a regular basis and to visit the beauty department for eyebrow and hair maintenance, which they were not to attempt on their own. Ginger had to use a depilatory cream on her faint mustache. Laura felt sheepish about all the primping, though she enjoyed the attention. She was most comfortable in a pair of pants and tennis shoes, walking through the dry Grif?th Park trails, with all the city laid out below her, still full of nothing but possibilities. It was the opposite of her parents’ land, at least at ?rst, where Laura knew every knot on every tree. There was still nature to discover in the world, an endless laundry list of sun-seeking plants and trees.

Ginger moved in a few houses down, and on the weekends the two women would often meet in the street, Clara running around their legs and Florence staggering back and forth between them. It was as though they were any two women in the world, generous with gossip and cups of tea. It wasn’t until some of the other neighborhood women began to gather on their front steps across the street to watch these interactions that Laura and Ginger moved their dates inside. It wasn’t a bother—who wouldn’t have noticed if two movie stars took a walk down the street together? Laura understood. This too was her job now, being Laura Lamont off the set as well as on. The children called her Mother or Mama, her parents and Josephine called her Elsa in their letters, Harriet called her Miss Emerson, and Ginger called her Laura, which was what she called herself. The trick seemed to be commitment: Elsa Emerson was a good Wisconsin girl. Laura Lamont was going to be a star.

Gordon stayed in their old house, a ?fteen-minute walk down Vermont Avenue. He saw the girls infrequently; at the beginning it had been once a week, but it was now no more than once a month, and never without supervision. Those were the lawyer’s rules. Laura would have been more generous, but the agreement was not up to her.

When he rang the bell, Clara ran into the kitchen and hid behind Harriet’s slender legs. “It’s okay,” Harriet said. “He does anything funny and I will knock him sideways.” She cupped Clara’s head with her palm.

“He won’t, though, will he?” Laura said. “I just don’t know.”

“Probably not,” Harriet said. “But if he does, sideways.” She nodded con?dently, as if only just truly agreeing with herself. “You should answer that, before he changes his mind.”

Laura picked up the baby and answered the door.

The rumors were everywhere at the studio. It was no crime to drink to excess; everybody did it, even Johnny, the boy wonder, who was so popular at the Santa Anita racetrack that he had his own viewing box. But nobody did it as often as Gordon. Sometimes Laura overheard other people talking about Gordon in the commissary, some young man dressed like a gondolier or an Indian chief, new faces who didn’t know she and Gordon had ever been married. The word was that he’d started doing other things too. There was a group of jazz musicians who had played a couple of parties on the lot. People said they’d seen Gordon with them out at night, places he shouldn’t have been. But then why were you there? Laura wanted to ask. How do you know so much, then? But she didn’t. Gordon Pitts was just another star in the Gardner Brothers galaxy now; why should Laura Lamont care about him? Sometimes she had to remind herself that the woman Gordon had married no longer existed. In some ways, she really had let Elsa Emerson stay on that bus—when her feet hit the California ground for the ?rst time, something inside had already shifted. Gordon wanted to be an actor, yes, of course he did, but not the way Laura did. He saw it as a fun job, a step up from working in the orange groves or at the grocery store. It was being far away from home that mattered most. There was nothing frivolous in Laura’s decision to leave Door County, no matter how quickly it had come about, even if she hadn’t quite been aware of it at the time. It was just something she had to do. Gordon could understand that about as well as he could understand how to engineer the Brooklyn Bridge. Some things were beyond his ken.

With Gordon at her door, though, it was harder to dismiss him. She saw the dark skin under Gordon’s eyes, black and pouchy. His shoulders rounded forward, as if the weight of the visit were already pulling him toward the ground. Laura stepped out of the way, inviting him in. Gordon shuf?ed past Florence and gave her toe a pinch. She howled, her tiny mouth a perfect circle of misery. Laura felt the sound deep inside her chest.

“Sorry,” Gordon said. His voice was low and scratchy, as though he’d been up all night talking.

Laura tapped a cigarette out of her pack and sat down in the living room, facing the still-whimpering Florence outward, toward her father. She gestured for Gordon to sit opposite her, and held her unlit cigarette over the baby’s head. It felt funny to have an ex-husband, a person out there in the universe who had shared her bed so many nights in a row and was now sleeping God knew where, and with God knew whom. Laura always assumed that she would be like her mother, and sleep alone only when her husband’s snoring got too loud. Instead, she was only twenty-two, and already groping around in the dark alone.

“Harriet?” Laura called into the air. She and Gordon sat in silence waiting for Harriet to come and take the baby away. Laura watched Gordon’s face as he stared at Florence. She’d just woken up from a nap and still had her sleepy, cloudy expression on.

“Is it true?” Gordon asked.

Harriet walked in and plucked Florence off Laura’s lap. She gave Laura a look that said, Just holler, and retreated toward the girls’ bedroom. Laura appreciated Harriet’s loyalty. So often it was just the two of them with the girls, a female family of four, and Harriet was protective of all of them in equal measure. Even though it had been only a few months, their time together had been so concentrated, so intimate, that Laura felt that Harriet knew her better than Gordon ever had. Laura waited until they were gone before responding, and even though she knew what he was referring to, Laura said, “Is what true?”

The living room wasn’t ?nished yet. There was a long, low sofa, and two high-backed chairs to sit on, and a coffee table, and a couple of lamps scattered around the room, like a half-built set, a facsimile of a lived-in space. There was an untouched chess set that the girls were always grabbing at, lamps that hadn’t been plugged in. Laura wondered whether her house would ever feel the way her parents’ house did, like no one else could have lived there and found everything. She wanted secret drawers and hidey-holes. Maybe when Clara was older, or when Florence was older—they were so close in age, like Josephine and Hildy. They would do everything together, the three of them, a package deal. She had a ?ickering thought about Irving, and whether he liked children. She hadn’t asked—why would she? It seemed presumptuous, when he had so much else to do.

“I mean about you and Irving Green.” Gordon could barely spit out the words.

Laura lit her cigarette, sure that the thought had registered on her face. Some thoughts burned too brightly to conceal. Laura tried to shift her attention to her cigarette, to the feel of the paper between her lips, and the bits of tobacco that landed on her tongue. “What about me and Mr. Green? He’s my boss, just like he’s your boss, Gordon.”

“He pays for this house, doesn’t he?” Gordon stood up and started walking the length of the room with his hands clasped tightly in front of him.

“He pays for your house too!” Laura tapped the end of her cigarette against the edge of the ashtray.

“But you’re sleeping with him.” Gordon stopped. He had his back to Laura and was looking out the wide window onto the street. The jacket Gordon was wearing had a small hole in one sleeve, and Laura couldn’t stop looking at it. All he had to do was ask—either her or the girls in wardrobe at the studio—and the hole would be gone in ?ve minutes. Had he not noticed? Or did he notice and not care? The ?rst time she’d gone in to meet with Irving, when her life with Gordon was still held together with pins, Gordon had stared at her getting ready, wearing a dress borrowed from Ginger, and then he’d told her she’d lost too much weight. Gordon had never wanted two actors in the same house, not really. He wanted a wife who sat on a kitchen chair and stared at the clock while he was gone. Sure, that was what most men counted on when they married, but Gordon had sworn up and down that he was different. No matter what whispered hopes they’d shared in the earliest weeks of their marriage, Gordon wanted to be married to another actor the way he wanted to be married to a gorilla—he just didn’t. It would never have worked; that was what Laura told herself. Their divorce wasn’t her fault, no more than Gordon’s drinking was.

Even so, Laura felt sorry for Gordon, staring at the hole in his sleeve. She perched her cigarette in the ashtray, its small smoke signal still reaching for the ceiling, and walked over to her husband. Her former husband. The lines were blurry—if they’d never been married, were they ever really divorced? There had been so many papers to sign, so many layers of con?dentiality promised. Laura couldn’t keep them straight. It wasn’t as though Gordon wanted custody of the girls—that was never a question. The girls belonged to Laura. She sometimes thought that she could have willed them into being all by herself, without a man’s help, if given enough time. And it wasn’t as though Gordon really loved her, either. They’d both imagined more for themselves, a real Hollywood-type romance, with ?owers and kisses underneath a lamppost. But he had believed her all those years ago, when they were sitting at her parents’ house, and she’d decided that he was the one. Gordon-from-Florida had bought every line. It wasn’t the loss of his own profound love that he was mourning, it was the loss of his belief in hers. Laura walked over to Gordon and put her arms around his waist, laying her body against his spine. He hadn’t known she was playing a part. Laura had always thought that, over time, the act would soften into the truth.

“I’m not,” Laura said. Louis Gardner had a wife, Maxine, and two plain-looking daughters, both of whom were enrolled in secondary school at Marlborough. Maxine always looked uncomfortable in furs and dresses with sequins on them, but Louis would drag her out anyway. People at the studio said horrible things, compared the three Gardner women to farm animals, though the girls were nice enough. Louis had been married for twenty-?ve years already, and Maxine predated any success. They’d worked at silent-?lm houses together in Pittsburgh. Laura couldn’t imagine Louis as a young man, without any of the trappings of power he surrounded himself with now. She imagined him like a paper doll, always the same, no matter the year, with little tabbed suits and ties to fold around his body. That was the kind of marriage she could have had with Gordon, if she’d been content to stay home. Irving Green had never been married—he wasn’t so much older than Laura, only in his early thirties, still a young man, despite all his success. He’d been too busy to get married, Laura thought. Plus, he’d never met the right girl.

“It’s okay,” Gordon said, without turning around. “I would too.”

Somewhere in the house, Florence wailed. Laura felt the nubby wool of Gordon’s jacket against her cheek. His body stiffened—the babies had not been his idea, as they hadn’t been hers. The girls had arrived, as children did, whether or not they were invited. Was that it? Maybe it wasn’t the drinking, or the fact that he and Laura had little in common except their shared desire to leave their hometowns and live big lives. Maybe it was that there were children, two tiny people who had not existed in the universe before. Laura felt sorry for Gordon; she could feel how badly he wanted to bolt, how unnatural it all felt to him. Some people couldn’t take care of a dog, let alone a child. Gordon seemed more and more like he was one of those people, doomed to always have empty cupboards and no plan beyond his evening’s entertainment.

Gordon shrugged out of Laura’s arms and walked himself to the front door. It was his last visit to the house, and more than ten years before either Clara or Florence saw their father in person again, and by then they needed to be reminded who he was.

Irving Green had an idea every thirty-?ve seconds. Laura liked to time him. Sometimes they were about her career, but sometimes they were just about the studio—he wanted to bring in elephants for a party, and offer rides. He wanted to hire a French chef for the commissary, to make crepes. Had she ever had a crepe? Irving told Laura that he’d take her to Paris for her twenty-?fth birthday. They hadn’t slept together yet; Laura hadn’t lied. But she would also be lying if she said she didn’t see it coming, cresting somewhere on the horizon. She’d heard things about his previous ?irtations, including Dolores Dee; there were so many pretty girls around, how could she expect to have been his ?rst temptation? And Laura wasn’t interested in being anyone’s ?ing. Before anything happened—before Paris, before sex—she would be a star, a real one, and there would be a ? rm under standing of exactly what was going on. Elsa hadn’t become Laura to become someone’s wife, and Irving had promised, though not in those exact words. What he’d actually said had more to do with what he wanted to do with Laura once she was his wife, and they were living in the same house. It made Laura blush even to think about it.

Irving had a part in mind, a movie about a nurse and a soldier. Nothing like the last movie. Ginger was a comedienne; that was what the studio had decided—let her stick with the funny stuff, the Susie and Johnny business. She did pratfalls and made goofy faces. Laura was something else—she was a real actress, Irving was sure. The movie was a drama about love torn asunder by war. No dance numbers, no parasols. He told Laura that she would have to dye her hair a good dark brown, the color of melting chocolate. As if she had a choice, Laura said yes, and started that night painting her eyebrows using a darker pencil.

He wanted to watch the hair girls do it. The hairdressers were used to Irving sitting in on important ?ttings with Cosmo and Edna, the costume designers, but it was unusual for a simple dye job, and made Laura even more nervous. Florence was so young—what if she didn’t recognize her? What if Clara hated it? When Laura told Ginger what they were planning to do, Ginger screwed up her face and shook her head. “Nope,” she said. “You’re a blonde, inside and out. This is just weird.” But Laura didn’t have a choice, and didn’t struggle when Irving led her to the chair by her elbow.

“Dark,” he said to the girls, who were already mixing a bowlful of nearly black goo. “Serious.”

“Scared.” Laura had never been anything but a blonde. Dark-haired people stood out in Door County like people who were missing a hand. Almost all of the natives were blond and fair, Norwegian or Swedish blood pumping strongly through their American veins. If she went back now, her mother and father would pause at the door, their hands still on the knob, unsure of whether or not to let her in. She locked eyes with Irving in the mirror. Bright, naked bulbs ringed his face like a halo, which seemed funny. Irving wasn’t an angel; he was a businessman, the ?rst she’d ever really known. Even though Irving was physically small and slight, with his famously bad heart ticking slowly inside him, Laura never thought of him that way—he had the con?dence of a lumberjack, or a lion tamer, or a black bear. Laura trusted him implicitly. If he wanted to dye her hair himself, she would have let him.

“This is going to be good for you,” Irving said. “You have to do it, Laura. I know it, trust me. This is going to be what sets you apart. Think about Susie—that’s a blonde, all surface, all air. You’re something different. You’re better.” He looked to the girls and nodded. “Do it.”

Laura shut her eyes tight and waited for them to start. The dye was thick and cold against her scalp, the way she imagined wet cement might feel. It didn’t take long, maybe an hour. One of the girls, a tiny blonde with rubber gloves up to her elbows, told Laura to open her eyes. First she held out her hand, and Irving took it, giving her ?ngers a quick squeeze.

“Look at yourself,” he said. “Laura Lamont, open your eyes.” His voice was gentle; he liked what he saw.

Laura blinked a few times, and focused on the stained towel in her lap, her free hand clutching at her dress. She looked up slowly, and by the time she made it to her own face in the mirror, she knew that Irving had been right. Her skin had always been pink; now it was alabaster. Her eyes had always been pale; now they were the ? rst things she saw, giant and blue.

“Wow,” she said, turning her head from side to side. “Look at me.” She covered her mouth with her hands, embarrassed at her own reaction.

Irving was already looking. He bent his knees to crouch beside her chair.

“Look at you,” Irving repeated. He kissed her on the forehead, and then on the mouth, and the girls pretended to be occupied in the back of the room. Irving’s lips were stronger than Laura anticipated, and pressed against her with the force of a man who had kissed many, many women before, and had no doubt in his own abilities. She closed her eyes and made him be the one to pull away. Once Irving straightened up and ran a hand over his hair, the hairdressers still tittering and chatting and washing things in the backroom sink, he helped Laura to her feet. Five-foot-seven when barefoot, Laura was taller than Irving by a few full inches, more in her high heels. Irving didn’t seem to mind, and so neither did she. In fact, Laura never thought about their difference in size ever again. It wasn’t every man who could make a woman forget that she was the larger in the pair, who could make a woman feel sexy when every part of her body was heavier, but Irving was that kind of man.

Laura pulled the hairdresser’s cape off her shoulders and set it down on the chair. She couldn’t take her eyes off herself in the mirror.

“So,” she said, shifting her gaze from her own re?ection to Irving’s. “Tell me about this part.”

The script was based on a novel written by a macho writer Laura had heard of, but never read, a writer her father loved. The Ballad of Bayonets was a period piece about the revolutionary war. Irving and Louis Gardner were betting on the audience’s desire to see an earlier war, one that was well resolved and in the past. Men around the studio were starting to enlist—several dolly grips and best boys, several actors, even some big names—Johnny made a big show of telling the press he would enlist if he could, but he had ?at feet and a bad ear. Some of the other studios were making war pictures too, and Laura kept her mouth shut around Irving, even though she worried it might all be in bad taste. Her contract was for twice what Gordon’s had been, and Irving assured her it was only the beginning.

Her character was a woman named Nellie Smith, and she fell in love with a wounded soldier she was nursing back to health after the loss of his right leg. Clara loved the idea of her mother as a nurse, and so Laura had two child-size versions of her nurse costume made for the girls. Clara wore hers to school every day, and Harriet reported that she rarely took it off when she came home, choosing instead to run tests on all the other children in the neighborhood.

Three days into the ?lm, the actor playing Laura’s love interest fell ill with appendicitis and had to be taken to the hospital. (“Isn’t that the point?” Ginger had joked. “That he’s supposed to be sick, and you’re supposed to take care of him?”) It was Irving’s idea to replace him with Gordon.

“Gordon Pitts?” Laura asked. “My Gordon?”

“He’s not your Gordon anymore,” Irving said, already holding the telephone in hand. His voice was hard, de?nite. There was no argument Laura could make that would sway him, she knew, but she tried anyway. She knew as well as Irving did that Gordon played broken better than anyone else on the lot.

“What about Johnny?” She knew it was a long shot. Johnny’d been out of Gardner Brothers’ favor as of late, thanks to a gambling problem he’d acquired while ?lming Las Vegas Is for Lovers, a romance about mistaken identity and shotgun weddings that culminated in a scene with Susie and Johnny racing from one chapel to the next, a herd of angry mobsters trailing behind them.

Irving held up a ?nger. Someone was on the other line. “Get me Gordon Pitts,” he said. “I don’t care what kind of hole you have to go down to ?nd him.” And that was that. Laura stood in the doorway as Irving called the director and wardrobe. Everything would need to be taken in.

“There,” he said when he was through. “That should make it more interesting.”

Gordon was late to the set every single morning. More than half the scenes were just the two of them, which meant that more often than not, Laura would arrive, get dressed, have her makeup done, and then sit in a canvas folding chair for an hour, watching grips carry things back and forth across the set. A ?ock of extras gathered nearby, all smoking in their knickers and bonnets. Peggy Bates had a real part, another nurse in the unit, and Laura was surprised at how calm she seemed after they called “Action,” how her nervous energy could be boxed up and put away. Nurses made Laura think about her sister Josephine, who had always hung around with nurses, and could have sewn together a wound without ? inching.

The ?rst day of shooting, when Gordon ?nally arrived a half hour late, he ambled over to the director, J. J. Rush, and began to apologize. J.J. wasn’t known for his patience, and Laura couldn’t help but watch as Gordon’s already stooped shoulders seemed to lower several more inches to the ground as J.J. laid into him. All the extras stomped on their cigarettes and scurried off to their proper places. When Gordon turned, his eyes swept over Laura and onto the rest of the set, only to backtrack—was it really her? When he realized he had already seen his former wife, Gordon stopped moving. Laura tried to sti?e a smile when Gordon clomped up to her.

“What did you do to yourself?” Gordon pointed at Laura’s head, in case she couldn’t tell what he was blabbering on about.

“Don’t you like it?” Laura put a hand under her hair, which the girls had curled into (she was fairly certain) historically inaccurate ringlets.

“You sure look different,” Gordon said. He narrowed his eyes, taking her in as if for the ? rst time.

The whites of Gordon’s eyes looked yellow. Laura had to resist the urge to back away. “Thank you,” Laura said, though she was sure he hadn’t meant it as a compliment.

The ?rst scene took place in Nellie’s farmhouse, somewhere in Virginia. Laura sat on the bed until there was a knock on the door. Gordon’s wounded soldier was on the other side, and she helped him in. They both still needed lines every so often, Gordon more often than Laura. The script girl moved so that she was closer to him. If necessary, J.J. said, they’d write all his dialogue out on cards. It had been done before. Laura wished that Gordon would pull it together: He was a good actor; she believed that. She never would have married a bad actor. When they had acted together in Door County, Gordon had had something better than average, a darker bloodline that ran much closer to the bone than most of the summertime boys. It wasn’t so different than it was for her, Laura imagined, watching Gordon murmur his lines to himself in between takes—there was a part of Gordon, buried deep inside his body, that he was trying to reach. The only real question Laura had was whether Gordon could stay close to the good part of himself, the actorly part, when this other, larger beast was trying to take over. Gordon coughed, and kept putting all his weight on the leg that was supposed to be shot and broken and infected. Everyone turned away and waited for him to ?nish.

“Sorry, J.J., I’m sorry,” he said, still hacking away. “There must be something caught in my throat.” When the script girl started rolling her eyes, Laura knew he was in trouble. Gordon coughed something up and spit it into his handkerchief.

The bonnet itched. The shoes were ?at and square, like something her mother would have worn. Laura was nervous that everything she thought showed on her face. The camera got so much closer than it ever had before. When it was her and Ginger in their matching dresses, the camera was never less than ten feet away, skimming over the surface of their youthful exuberance. Now the camera’s lens hovered over her like a lover, its open, round eye coming ever closer.

“Is Irving here?” They were in between shots, and Laura couldn’t breathe. There were too many layers of clothing, and Edna, the assistant costume designer, had wound too many ribbons around her neck, which began to feel as if it were being strangled. She started tugging at them, and wandered off the set, out of the three walls of the farmhouse, and onto the concrete ?oor of the soundstage. Several voices shouted at once, and the quick feet of grips and assistant cameramen ran off to ?nd him. Laura stared at the ground, unable to move. A strand of her hair had fallen out and clung to her sleeve. She picked it up by its end like a worm in the garden and tried to ?ing it off, but it wouldn’t go. “Can someone call Irving Green, please?” Edna hurried over, her legs moving as quickly as her narrow skirt suit would allow. There were pins sticking out of the hem of her skirt, and a little cushion strapped to the back of her hand. She knelt down next to Laura and loosened several items at once, her tiny, birdlike hands moving furiously. Laura moved onto her hands and knees, as though she were playing with Clara and Florence on her own rug at home and not surrounded by grown-up people who might think ill of her if she began to vomit. Her neck, it was her neck. She should have remembered to tell them she couldn’t have anything on it; she should have told them that her neck was off-limits, nonnegotiable, no matter what the costume designer said.

“Laura, what’s going on?” Irving arrived quickly, relieving Edna. He’d been in his of?ce bungalow, where he almost always slept and ate all of his meals. If nothing else, Irving Green was an easy man to ?nd. Despite his presence, which did calm Laura a bit, the room was too warm still, and her entire body felt damp and feverish. Laura held out her hand, and Irving helped her stand up. The extras all pretended to look away, but Laura knew how strong the impulse was to get Irving’s attention.

“I don’t think I can do it,” she said softly, so that only he could hear. “I couldn’t breathe.” Laura pulled at her collar, trying to free up her heart, which was booming against her jaw, and felt as if it were about to burst.

“Why, because of Gordon?” He sounded so disappointed, as if she had let him down personally. He had expected more. Irving adjusted his glasses, and then leaned down to pick up the bonnet that had been tied tightly under Laura’s chin, and the ribbons that had been so tight around her throat. “That’s too much, don’t you think?” Irving craned his neck, looking for Edna, who was still nearby. He wasn’t talking to Laura anymore. Edna came over with a pair of scissors and snipped a few more things off, opening up Laura’s costume so that her neck was free. Edna’s small eyes focused on parts of Laura that only the camera would see. Hair and makeup rushed over to ?uff Laura’s ringlets.

“No,” Laura said, although she wasn’t sure whether she was telling the truth. She looked at Gordon, who kept readjusting his hat. He did look sickly. The casting had been good; as usual, Irving was right. “I’ve never had to be serious before. In front of the camera, I mean.” In the theater, there were always people sitting right in front of you. Even with the few meager lights that her father had rigged in the barn, Laura could make out one person’s nose, or another person’s laugh. The audience had been right there with her, and she could react. What choice did she have now, to react to Gordon? Just looking at him made her sad. No, Laura thought, no. She could do it. When the nurse looked down at the soldier’s gangrenous leg, its oozing and bleeding mess, she would see her husband and her own broken heart. Gordon hadn’t broken it—no, Laura doubted that he would even know how. She had broken it herself when she’d climbed aboard that bus in Chicago, when she knew that she was hitching her wagon to Gordon’s only temporarily. When she watched her father hold his own elbows and not turn away until the bus was gone, maybe not even then. Her father probably waited in that depot for hours, wanting to be there if she changed her mind and decided to come back. That was what she would see when she looked at Gordon; she would be Elsa, saying good-bye to her former life, her happy childhood and her sad one, all at once. Laura thought of Hildy’s body and put her hands back to the collar of her dress, pulling it down and away from her face. She could heal Gordon’s leg with her bare hands if she had to.

At night, someone would drive Laura home. Gardner Brothers had a ?eet of cars, and Irving insisted. It was pleasant not to have to drive: Laura enjoyed waving good-bye to whoever was around and then folding herself into the backseat of a waiting car. Once inside, she could shut her eyes and lean her face against the leather headrest. She hadn’t been in such nice cars before, and after the ? rst few trips, Laura stopped telling the drivers where to go, because they had obviously already been informed. It was an odd feeling, that strangers knew who she was and where she lived, and that they cared, but Laura could get used to odd.

Harriet put the girls to bed and waited for Laura to have dinner, though Laura would never eat much. They sat together at the small kitchen table and whispered about the days, as if speaking in their regular voices would wake the girls up.

“Florence walked like a mermaid all afternoon,” Harriet said. “Every time she took a step, she said, ‘Squish, squish, squish.’” “Oh, no,” Laura said, her eyes widening with pride. “She’s an actress.”

“Some spice cake?” Harriet got up to clear their plates.

“I shouldn’t.”

Harriet brought over two plates with tiny slivers of cake. “Just a smidge. Hardly counts.” Laura nudged a bit of cake onto her fork and put the bite on her tongue, closing her lips around the fork. In every house Laura had ever lived in, the kitchen was always her favorite room, the place where conversations actually happened, rather than where they pretended to. It didn’t matter how tired she was, and how long her day would be tomorrow. It was nice to be at home. Across the table, Harriet ate her piece in two swallows. “Let me get you another,” Laura said. “They were awfully small pieces.”

Harriet leaned back and hooked her hands behind her head. “I won’t say no to that,” she said, and laughed.

The ?lming went on longer than expected, nearly three months. Gardner Brothers rented an abandoned lot in Echo Park for the battle sequences. Laura appeared in only the ?nal one, when she waded through the dead and dying men strewn about the ?eld in search of Gordon’s soldier. She found him dead, his healed leg having swiftly delivered him to the front lines of the war. When Laura collapsed over Gordon’s body, she smelled his sweat and his foul breath, and the tears that she shed were real. When the ?lm was released, the studio leaked photos of the ?nal scene, and Laura’s mascara-streaked face, to the “Facts of Hollywood Life” column in Photoplay magazine, which screamed that the two actors were in love. Only the people on the Gardner Brothers lot knew the truth, and they weren’t talking. It all seemed so silly, so backward: When Laura and Gordon really were married, no one had cared, but now that she wanted nothing to do with him, everyone wanted to take their photo and whisper behind their backs. When Irving asked Laura and Gordon to sit next to each other at the premiere, they did so. Gordon sucked gin out of his ?ask throughout the entire ?lm, clinking glasses with all the well-wishers. Laura couldn’t stand to be next to him, but when the spotlight found them, she let him kiss her on the cheek. His lips were dry and cracked, no matter what the makeup girls put on him. Whatever he was putting inside his body was stronger. The girls were at home with Harriet; Irving was in the balcony with Louis Gardner and his stout family. The Ballad of Bayonets showed on screens all over the country, in movie houses large and small, and Laura Lamont was a star, through and through. The newspaper photographers snapped her photo when she left the theater alone, her white stole dragging behind her like a child’s security blanket.

The announcement went out on the wires the morning after the opening: Gordon Pitts was so moved by his role that he had chosen to enlist in the United States Armed Forces, and he would be shipping off to basic training that afternoon. Louis Gardner was quoted as saying that he was proud of Gordon, as he was proud of all his employees who had chosen to serve their country. Such bravery! Such sel?essness! Hearts were stirred from Santa Monica to Pasadena. Laura went to Irving’s bungalow when she heard the news, thirdhand, from Ginger, who had shrugged.

“Did you know?” Laura asked, once one of Irving’s ?eet of secretaries had noiselessly shut the door. “Did you know he was going to do that?”

Irving took off his glasses and held them up toward the light. “In fact, I did.”

“Gosh,” Laura said, as she sank into the chair opposite his. She dropped her purse onto the ?oor. “I never took him for a soldier type. Or anything even close. I guess I didn’t know him very well at all. I’m sort of impressed.”

Irving sti?ed a laugh. “Oh, Laura.” He got up and walked around the desk, toward the window that overlooked the lot. “I told Gordon Pitts that if he didn’t get out of town, he would never work again. Not at Gardner Brothers, and not anywhere else.” He ?ngered the blinds, peeking out into the world that he controlled. The Gardner Brothers water tower stood spitting distance from his window, the studio emblem painted ten feet high. You could see the water tower from anywhere in the lot, even from the cemetery on the other side of the lot’s walls—you could see it from the studio next door. To see it out Irving’s window reminded Laura that she was not the one in charge, no matter what she did.

Laura cocked her head to the side. “You made him go? To war?”

“Oh, they’ll kick him around different training camps for months,” Irving said, turning to face her. “He’ll learn to shoot, to run. It’ll be good for him. Who knows if he’ll even see any real action. I’m not putting him to death, Laura, I’m not sending him to Hitler on a silver platter.”

She was still working it out in her head. Gordon was gone—he wouldn’t bother the girls, wouldn’t ring her doorbell, wouldn’t breathe his hot breath on her cheek. “You did that for me?” It was wrong of Irving, potentially lethal, and yet she was moved.

“You bet I did,” Irving said. “I’d do it again too. That guy was a prick.”

Laura laughed, but stopped herself quickly. “And Louis approved it? It’s okay?” She tried to imagine Gordon in uniform, a real uniform instead of a costume, but realized she didn’t know the difference. “Oh, God,” Laura said, shaking her head.

“It’s done, it’s done,” Irving said. “People will like Gordon more now. That’s what I told him, and it’s true.”

Laura moved across the room to Irving. She held out her hands, and he took them, rubbing his thumbs over her knuckles. “Would you ever do it? Sign up, I mean?”

“Oh, they wouldn’t take me. Too many childhood illnesses. Fluid in the wrong places. Hole in the heart. I’m like something out of a Victorian orphanage.” And just like that, Irving con?rmed everything she’d ever heard about him, as nonchalantly as if he were placing an order for dinner. Laura was glad he’d been a sick child: It meant that she could have him now, and keep him forever. He looked at her and smiled, as if amused at the expression on her face.

“And what about me?” Laura asked.

“What about you?” Irving sat on his desk and crossed his arms over his chest, amused.

“Shouldn’t I do something too? Sell some bonds? Visit some troops?”

Irving shook his head. “Leave that to the Dolores Dees of the world. All you need to do is spend a couple shifts at the Hollywood Canteen. We need you here, my dear.”

“Well, then,” Laura said, and folded herself against him, her lips against his neck, then his cheek, then his mouth. “If you say so.”

Fall 1941

The studio lawyers made everything easy: Within two years of her initial contract, Elsa was divorced and Laura had never been married. Gardner Brothers represented both Laura and Gordon, though it was easy to see whom the bosses favored. Who was Gordon but a sidekick, a bit player? Louis Gardner arranged to help Laura ?nd a bigger house, perfect for her and the two girls and one nanny. It was so easy to change a name: Clara and Florence became Emersons, as they should have been from the start. Elsa couldn’t believe she’d ever let herself or her daughters carry the name Pitts. The lawyers never charged Laura for their time: It was all in the contract. No one in the papers asked the questions Laura thought they might: If you’ve never been married, where did these two girls come from, the stork? Questions that did not follow the script were simply not allowed. The divorce had been Elsa’s idea, which was to say it had been Laura’s idea too. She found that there were certain activities (feeding the children, taking a shower) that she always did as Elsa, and others (going to dance class, speaking to Irving and Louis) that

she did as Laura, as though there were a switch in the middle of her back. The problem had been that neither Elsa nor Laura wanted to be married to Gordon, who wanted to be married only to Elsa. Before the girls were born, Gordon seemed happy enough for Elsa to be an actress, but not when she was the mother of his children.

Clara spent her days in the on-set school with all the other kids, though Florence was only a baby and stayed home with Harriet, the nanny, who was the ?rst black woman Laura had ever really known and charged as much per week as the lead actors at the Cherry County Playhouse. Harriet was exactly Laura’s age and had a kind, easy way with all three of the Emerson girls. The new house was on the other side of Los Feliz Boulevard, on a street that snaked up into the hills. Sycamore trees hung low over the sidewalks, and Laura loved to take long walks with Harriet and the girls, pointing out squirrels and even the occasional opossum. Grif?th Park wasn’t technically Laura’s backyard, but that was how she liked to think of it. She went to every concert she could at the Greek Theatre and at the Hollywood Bowl, which wasn’t often but often enough, and far more often than if she had stayed in Door County, Wisconsin. She sat outside, under the stars, with all of Los Angeles hushed and quiet behind her; Laura felt that she was once again sitting in the patch of grass outside the Cherry County Playhouse, and every note was sung just for her. One evening, a secretary found Laura on her way from the day care to dance class, and stopped her in her tracks. Irving Green had a box at the Hollywood Bowl, and wanted Laura to be his date for the evening. It was never clear how Irving came to possess all the pieces of information he did, just that he was very good at ?nding things out and holding them all inside his brain until he needed them. Laura said yes, which neither pleased nor surprised the secretary, and Harriet stayed home with the girls. Irving and his driver came to pick her up at six, before dusk, and they sat in near silence until they reached their destination, which gave Laura ample time to examine the inside of the automobile, which was the ?rst Rolls-Royce she’d ever seen up close. When they arrived at the Hollywood Bowl, ushers quickly showed them to their seats, which were inches from the stage, so close that Laura could have reached out and grabbed the ? rst violinist’s bow if she’d had the urge. A few minutes in, an usher hurried over to Irving’s side, whispered in his ear, and they ducked out again. Laura fussed nervously, sure that everyone in Los Angeles was staring straight at her, wondering why she’d been chosen as his date at all, and sure that he probably wasn’t coming back. When Irving returned a few minutes later, he said only, “Garbo,” as if that were all that was necessary, and it was.

“I’ve been meaning to ask you,” Laura said, in between movements. The seats around them were empty; the Bowl wasn’t always full, she knew from her time in the cheap seats several hundred feet from where they were sitting, but even so, Laura imagined that Irving was behind their seclusion, that he held unseen power here as on the lot. “Why ‘Brothers,’ when it’s only Louis? Isn’t that misleading?” She blushed at her wrong choice of words—she hadn’t meant misleading, which implied that Louis, their boss and Irving’s mentor, was hoodwinking the audiences. She’d meant secretive, or goofy, even, something that she hadn’t communicated. Laura was nervous whenever she was alone with Irving, whether it was in his of?ce or the few times she’d seen him walking purposefully around the lot. There were things everyone on the lot knew about Irving, things Laura had overheard: He’d been sick as a child, and there was something wrong still, a weakness in a ventricle (so said Edna, the costume assistant) or a lung (so said Peggy, a devoted gossip). Laura didn’t think she’d ever be bold enough to ?nd out the truth. Eating together was the worst: Irving hardly touched his food, swallowing tinier bites than Laura knew was possible and pronouncing himself stuffed. The desire for him to like her was so strong she could barely think. Laura thought of the ?rst time they’d met, and how silly she’d found all those actors pretending to examine their shoes when all they really wanted was his attention. Now she was just as guilty. He was a father ?gure to all of them, and most of the actors weren’t afraid to get scrappy with their siblings.

“Oh,” Irving said, “that. I told Louis I thought it sounded better.”

The orchestra began playing a selection from Così fan Tutte. Strings soared up into the sky, and Laura felt as if the entire park were ?lled with bubbles. She laughed and turned her head toward the sky, as if the stars would laugh back at her.

“That’s rich,” Laura said. “That’s rich.”

Irving reached over and put her hand in his, never turning his eyes away from the stage. His skin was soft and not nearly as cold as she imagined it would be, and even though Laura’s hand began to perspire, Irving didn’t pull away. Laura knew that from the cheap seats, the Hollywoodland sign was visible on the hills behind the dome of the Bowl, and she felt it there, ?ashing in the darkness like an electric eel. They sat quietly for the rest of the concert, ostensibly listening to the music, though Laura could hear nothing except the sound of her own heart beating wildly within her chest. Garbo may have been on the phone, but Laura was there, right there, sitting beside him, feeling the bones in Irving’s surprisingly strong grip.

The ?rst starring role Irving gave to Laura was in a ?lm with Ginger, Kissing Cousins—they played sisters, which made them both squeal with excitement. Laura was blond and Ginger was red, which meant that Ginger was the saucy one, and Laura was the innocent. The sisters were from Iowa and had moved to Los Angeles to be stars. It was a simple story, with lots of ?irting and costume changes. Laura’s favorite scene involved the girls dancing clumsily around a café, threatening to poke the other patrons’ eyes out with their parasols. She loved being in front of the camera, loved the weight of the thick crinolines under her dress, loved the elaborate hats made of straw and feathers. Acting in an honest-to-goodness motion picture was the ?rst thing Laura had done that made her think of Hildy without feeling like she’d been socked in the jaw—Hildy would have loved every inch of ?lm she’d shot, every dip and twirl, and that made Laura feel like she would have done it all for free. Of course she would have! Every actor and actress on the lot would have worked for free; that was the truth. Gardner Brothers didn’t know the depth of desire that was on its acres, not the half of it.

There were differences between acting onstage and on-screen; Laura felt the gulf at once. At the playhouse, choices were made on a nightly basis, always prompted by the feelings in the air, by the choices made by the actors around you. There were slight variations, almost imperceptible, sometimes caused by a tickle in your throat or a giant lightning bug zipping across the stage. On ?lm, choices were made over and over again, a dozen times in a row, from this angle and that, with close-ups and long shots and cranes overhead. The movements were smaller, the voice lower. Laura beamed too widely, sang too loudly. Everything had to be brought down, and done on an endless loop. She and Ginger skipped in circles for hours, it seemed, their hoop skirts knocking against each other like soft, quick-moving clouds hurrying across the sky.

Kissing Cousins was a modest hit, and though the critics called it “a lesser entry into the Johnny and Susie canon, though without the star power those two pint-sized powerhouses might have lent,” moviegoers responded to Laura’s sweetness on-screen. She got fan mail at the studio: whole bags of letters from teenage girls who wanted to know how she got her hair to do that, what color lipstick she liked best. One boy wrote and asked her to marry him. She kept that one; the rest she passed along to the secretaries at the studio, one of whom was now devoted just to her and Ginger, the new girls in town. Irving and Louis had her pose for photos—a white silk dress, gardenias in her hair—that could be signed and sent out to her fans. The dress was the most expensive thing Laura had ever felt against her skin, and she wore it for as long as possible before Edna asked for it back. Laura had fans: a small but growing number. Irving Green and all the imaginary Gardner Brothers brothers made sure of it.

On top of the dance classes (Guy, chastened by the girls’ newfound success, left them alone in the back of the class, and they did improve, slowly, at both the ronds de jambe and the poker faces necessary to survive the class period), Laura and Ginger were now required to shave their legs on a regular basis and to visit the beauty department for eyebrow and hair maintenance, which they were not to attempt on their own. Ginger had to use a depilatory cream on her faint mustache. Laura felt sheepish about all the primping, though she enjoyed the attention. She was most comfortable in a pair of pants and tennis shoes, walking through the dry Grif?th Park trails, with all the city laid out below her, still full of nothing but possibilities. It was the opposite of her parents’ land, at least at ?rst, where Laura knew every knot on every tree. There was still nature to discover in the world, an endless laundry list of sun-seeking plants and trees.

Ginger moved in a few houses down, and on the weekends the two women would often meet in the street, Clara running around their legs and Florence staggering back and forth between them. It was as though they were any two women in the world, generous with gossip and cups of tea. It wasn’t until some of the other neighborhood women began to gather on their front steps across the street to watch these interactions that Laura and Ginger moved their dates inside. It wasn’t a bother—who wouldn’t have noticed if two movie stars took a walk down the street together? Laura understood. This too was her job now, being Laura Lamont off the set as well as on. The children called her Mother or Mama, her parents and Josephine called her Elsa in their letters, Harriet called her Miss Emerson, and Ginger called her Laura, which was what she called herself. The trick seemed to be commitment: Elsa Emerson was a good Wisconsin girl. Laura Lamont was going to be a star.

Gordon stayed in their old house, a ?fteen-minute walk down Vermont Avenue. He saw the girls infrequently; at the beginning it had been once a week, but it was now no more than once a month, and never without supervision. Those were the lawyer’s rules. Laura would have been more generous, but the agreement was not up to her.

When he rang the bell, Clara ran into the kitchen and hid behind Harriet’s slender legs. “It’s okay,” Harriet said. “He does anything funny and I will knock him sideways.” She cupped Clara’s head with her palm.

“He won’t, though, will he?” Laura said. “I just don’t know.”

“Probably not,” Harriet said. “But if he does, sideways.” She nodded con?dently, as if only just truly agreeing with herself. “You should answer that, before he changes his mind.”

Laura picked up the baby and answered the door.

The rumors were everywhere at the studio. It was no crime to drink to excess; everybody did it, even Johnny, the boy wonder, who was so popular at the Santa Anita racetrack that he had his own viewing box. But nobody did it as often as Gordon. Sometimes Laura overheard other people talking about Gordon in the commissary, some young man dressed like a gondolier or an Indian chief, new faces who didn’t know she and Gordon had ever been married. The word was that he’d started doing other things too. There was a group of jazz musicians who had played a couple of parties on the lot. People said they’d seen Gordon with them out at night, places he shouldn’t have been. But then why were you there? Laura wanted to ask. How do you know so much, then? But she didn’t. Gordon Pitts was just another star in the Gardner Brothers galaxy now; why should Laura Lamont care about him? Sometimes she had to remind herself that the woman Gordon had married no longer existed. In some ways, she really had let Elsa Emerson stay on that bus—when her feet hit the California ground for the ?rst time, something inside had already shifted. Gordon wanted to be an actor, yes, of course he did, but not the way Laura did. He saw it as a fun job, a step up from working in the orange groves or at the grocery store. It was being far away from home that mattered most. There was nothing frivolous in Laura’s decision to leave Door County, no matter how quickly it had come about, even if she hadn’t quite been aware of it at the time. It was just something she had to do. Gordon could understand that about as well as he could understand how to engineer the Brooklyn Bridge. Some things were beyond his ken.

With Gordon at her door, though, it was harder to dismiss him. She saw the dark skin under Gordon’s eyes, black and pouchy. His shoulders rounded forward, as if the weight of the visit were already pulling him toward the ground. Laura stepped out of the way, inviting him in. Gordon shuf?ed past Florence and gave her toe a pinch. She howled, her tiny mouth a perfect circle of misery. Laura felt the sound deep inside her chest.

“Sorry,” Gordon said. His voice was low and scratchy, as though he’d been up all night talking.

Laura tapped a cigarette out of her pack and sat down in the living room, facing the still-whimpering Florence outward, toward her father. She gestured for Gordon to sit opposite her, and held her unlit cigarette over the baby’s head. It felt funny to have an ex-husband, a person out there in the universe who had shared her bed so many nights in a row and was now sleeping God knew where, and with God knew whom. Laura always assumed that she would be like her mother, and sleep alone only when her husband’s snoring got too loud. Instead, she was only twenty-two, and already groping around in the dark alone.

“Harriet?” Laura called into the air. She and Gordon sat in silence waiting for Harriet to come and take the baby away. Laura watched Gordon’s face as he stared at Florence. She’d just woken up from a nap and still had her sleepy, cloudy expression on.

“Is it true?” Gordon asked.

Harriet walked in and plucked Florence off Laura’s lap. She gave Laura a look that said, Just holler, and retreated toward the girls’ bedroom. Laura appreciated Harriet’s loyalty. So often it was just the two of them with the girls, a female family of four, and Harriet was protective of all of them in equal measure. Even though it had been only a few months, their time together had been so concentrated, so intimate, that Laura felt that Harriet knew her better than Gordon ever had. Laura waited until they were gone before responding, and even though she knew what he was referring to, Laura said, “Is what true?”

The living room wasn’t ?nished yet. There was a long, low sofa, and two high-backed chairs to sit on, and a coffee table, and a couple of lamps scattered around the room, like a half-built set, a facsimile of a lived-in space. There was an untouched chess set that the girls were always grabbing at, lamps that hadn’t been plugged in. Laura wondered whether her house would ever feel the way her parents’ house did, like no one else could have lived there and found everything. She wanted secret drawers and hidey-holes. Maybe when Clara was older, or when Florence was older—they were so close in age, like Josephine and Hildy. They would do everything together, the three of them, a package deal. She had a ?ickering thought about Irving, and whether he liked children. She hadn’t asked—why would she? It seemed presumptuous, when he had so much else to do.

“I mean about you and Irving Green.” Gordon could barely spit out the words.

Laura lit her cigarette, sure that the thought had registered on her face. Some thoughts burned too brightly to conceal. Laura tried to shift her attention to her cigarette, to the feel of the paper between her lips, and the bits of tobacco that landed on her tongue. “What about me and Mr. Green? He’s my boss, just like he’s your boss, Gordon.”

“He pays for this house, doesn’t he?” Gordon stood up and started walking the length of the room with his hands clasped tightly in front of him.

“He pays for your house too!” Laura tapped the end of her cigarette against the edge of the ashtray.

“But you’re sleeping with him.” Gordon stopped. He had his back to Laura and was looking out the wide window onto the street. The jacket Gordon was wearing had a small hole in one sleeve, and Laura couldn’t stop looking at it. All he had to do was ask—either her or the girls in wardrobe at the studio—and the hole would be gone in ?ve minutes. Had he not noticed? Or did he notice and not care? The ?rst time she’d gone in to meet with Irving, when her life with Gordon was still held together with pins, Gordon had stared at her getting ready, wearing a dress borrowed from Ginger, and then he’d told her she’d lost too much weight. Gordon had never wanted two actors in the same house, not really. He wanted a wife who sat on a kitchen chair and stared at the clock while he was gone. Sure, that was what most men counted on when they married, but Gordon had sworn up and down that he was different. No matter what whispered hopes they’d shared in the earliest weeks of their marriage, Gordon wanted to be married to another actor the way he wanted to be married to a gorilla—he just didn’t. It would never have worked; that was what Laura told herself. Their divorce wasn’t her fault, no more than Gordon’s drinking was.

Even so, Laura felt sorry for Gordon, staring at the hole in his sleeve. She perched her cigarette in the ashtray, its small smoke signal still reaching for the ceiling, and walked over to her husband. Her former husband. The lines were blurry—if they’d never been married, were they ever really divorced? There had been so many papers to sign, so many layers of con?dentiality promised. Laura couldn’t keep them straight. It wasn’t as though Gordon wanted custody of the girls—that was never a question. The girls belonged to Laura. She sometimes thought that she could have willed them into being all by herself, without a man’s help, if given enough time. And it wasn’t as though Gordon really loved her, either. They’d both imagined more for themselves, a real Hollywood-type romance, with ?owers and kisses underneath a lamppost. But he had believed her all those years ago, when they were sitting at her parents’ house, and she’d decided that he was the one. Gordon-from-Florida had bought every line. It wasn’t the loss of his own profound love that he was mourning, it was the loss of his belief in hers. Laura walked over to Gordon and put her arms around his waist, laying her body against his spine. He hadn’t known she was playing a part. Laura had always thought that, over time, the act would soften into the truth.

“I’m not,” Laura said. Louis Gardner had a wife, Maxine, and two plain-looking daughters, both of whom were enrolled in secondary school at Marlborough. Maxine always looked uncomfortable in furs and dresses with sequins on them, but Louis would drag her out anyway. People at the studio said horrible things, compared the three Gardner women to farm animals, though the girls were nice enough. Louis had been married for twenty-?ve years already, and Maxine predated any success. They’d worked at silent-?lm houses together in Pittsburgh. Laura couldn’t imagine Louis as a young man, without any of the trappings of power he surrounded himself with now. She imagined him like a paper doll, always the same, no matter the year, with little tabbed suits and ties to fold around his body. That was the kind of marriage she could have had with Gordon, if she’d been content to stay home. Irving Green had never been married—he wasn’t so much older than Laura, only in his early thirties, still a young man, despite all his success. He’d been too busy to get married, Laura thought. Plus, he’d never met the right girl.

“It’s okay,” Gordon said, without turning around. “I would too.”

Somewhere in the house, Florence wailed. Laura felt the nubby wool of Gordon’s jacket against her cheek. His body stiffened—the babies had not been his idea, as they hadn’t been hers. The girls had arrived, as children did, whether or not they were invited. Was that it? Maybe it wasn’t the drinking, or the fact that he and Laura had little in common except their shared desire to leave their hometowns and live big lives. Maybe it was that there were children, two tiny people who had not existed in the universe before. Laura felt sorry for Gordon; she could feel how badly he wanted to bolt, how unnatural it all felt to him. Some people couldn’t take care of a dog, let alone a child. Gordon seemed more and more like he was one of those people, doomed to always have empty cupboards and no plan beyond his evening’s entertainment.

Gordon shrugged out of Laura’s arms and walked himself to the front door. It was his last visit to the house, and more than ten years before either Clara or Florence saw their father in person again, and by then they needed to be reminded who he was.

Irving Green had an idea every thirty-?ve seconds. Laura liked to time him. Sometimes they were about her career, but sometimes they were just about the studio—he wanted to bring in elephants for a party, and offer rides. He wanted to hire a French chef for the commissary, to make crepes. Had she ever had a crepe? Irving told Laura that he’d take her to Paris for her twenty-?fth birthday. They hadn’t slept together yet; Laura hadn’t lied. But she would also be lying if she said she didn’t see it coming, cresting somewhere on the horizon. She’d heard things about his previous ?irtations, including Dolores Dee; there were so many pretty girls around, how could she expect to have been his ?rst temptation? And Laura wasn’t interested in being anyone’s ?ing. Before anything happened—before Paris, before sex—she would be a star, a real one, and there would be a ? rm under standing of exactly what was going on. Elsa hadn’t become Laura to become someone’s wife, and Irving had promised, though not in those exact words. What he’d actually said had more to do with what he wanted to do with Laura once she was his wife, and they were living in the same house. It made Laura blush even to think about it.