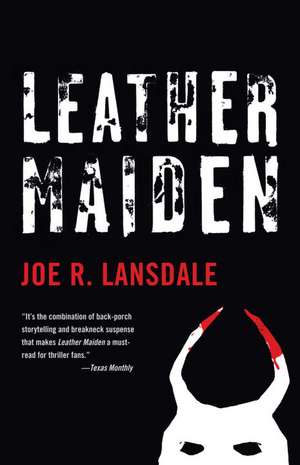

Leather Maiden

Autor Joe R. Lansdaleen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 iul 2009

After a harrowing stint in the Iraq war, Cason Statler returns home to the small East Texas town of Camp Rapture, where he drinks too much, stalks his ex-wife, and takes a job at the local paper, only to uncover notes on a cold case murder. With nothing left to live for and his own brother connected to the victim, he makes it his mission to solve the crime. Soon he is drawn into a murderous web of blackmail and deceit. To makematters worse, his deranged buddy Booger comes to town to lend a helping hand.

Preț: 96.74 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 145

Preț estimativ în valută:

18.51€ • 19.38$ • 15.32£

18.51€ • 19.38$ • 15.32£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 15-29 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780375719233

ISBN-10: 0375719237

Pagini: 304

Dimensiuni: 132 x 203 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Editura: Vintage Crime/Black Lizard

ISBN-10: 0375719237

Pagini: 304

Dimensiuni: 132 x 203 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Editura: Vintage Crime/Black Lizard

Notă biografică

Joe R. Lansdale has written more than a dozen novels in the suspense, horror, and Western genres. He has also edited several anthologies. He has received the British Fantasy Award, the American Mystery Award, and seven Bram Stoker Awards from the Horror Writers of America. He lives in East Texas with his wife, son, daughter, and German Shepherd.

Extras

When you grow up in a place, especially if your childhood is a good one, you fail to notice a lot of the nasty things that creep beneath the surface and wriggle about like hungry worms in rotten flesh. But they’re there. Sometimes you have to dig to discover them, or slant your head in just the right direction to see them. But they’re there all right, and the things that wriggle can include blackmail, mutilation and murder. And I can vouch firsthand that this is true.

But the day I arrived back in town there was no evidence of anything wriggling under the surface or anywhere else, unless you count my head, which seemed to be wriggling a lot. I was coming off a lowball drunk and felt as if someone had borrowed my skull to bowl a few frames.

As I drove through Camp Rapture, over the railroad tracks and past the dog food factory, I told myself I would never drink again. But I had told myself that before.

It was a bright day, the sunlight like a burst egg yolk running all over the sidewalk and through the yards, almost snuffing out the grass with its heated glory, and causing everything to be warm and appear fresh, even the houses on the poor side of town from which ancient coats of basic white peeled like stripping sunburn.

I tooled along with my eyes squinted to keep out some of the summer light, eased by Gabby’s veterinarian office and tried not to rubberneck too much, and passed on. I finally drove up to the Camp Rapture Report, got out and stood by my aging car and looked around and hoped maybe this time things were going to go better.

Night before, I had driven over from Houston after leaving Hootie Hoot, Oklahoma, and my crazy Iraq war buddy, Booger, but only got as far as a bar, and later a motel on the outskirts of town, where I drank myself into a stupor in front of the TV set, watching who knows what. For all I cared it could have been a program on tractor repair or how to give yourself a lobotomy.

Next morning, I awoke feeling like something had died in my mouth and something else had crawled up my ass. I showered and brushed the dead thing out of my mouth and decided to live with whatever was up my ass, and drove to my scheduled interview for a possible position on the Camp Rapture Report.

Standing there beside my car, sweating from the late summer heat like a great ape in an argyle sweater, I took in a big breath of hot air. I checked to make sure my zipper was up, then examined the bottoms of my shoes for dog crap, just in case. I went along the sidewalk, strolled past the bee-laden, flowered shrubbery, the smell of which made my stomach roil, and went inside.

The Report looked pretty old-fashioned. Like a place where male reporters ought to wear fedoras with press cards in the hatbands and the female reporters ought to chew gum and talk snappy dialogue through bright red lipstick.

At the front desk I was greeted by a cute blond lady. She smiled and showed me some braces. I think she was in her mid-twenties, possibly even a little older, closer to my age, but the braces and the hairdo, which was too short and not evenly cut, along with a scattering of freckles that decorated her flushed cheeks, made her look like a spunky 1950s schoolkid as seen under a huge magnifying glass.

“Mr. Statler,” she said. “How are you?”

“You remember me?”

“We went to school together.”

“We did?”

“Belinda Hickam. I was a year under you. You were in the journalism club and you wrote for the high school paper. I think you wrote about chess.”

“Actually I only wrote one article about chess.”

“I guess that was the one I read. You’ve been hired to do a column, right?”

“I haven’t been hired yet.”

“Well, I’m going to be optimistic about it. Mrs. Timpson is waiting to see you.”

“Which way?” I said.

She pointed at a foyer where I could see a heap of stacked boxes, advised me to start in that direction and she would buzz Mrs. Timpson that I was on my way back.

“Any advice?” I asked.

“Keep your hands and feet on the visitor’s side of the desk, don’t make any sudden moves, and try not to make direct eye contact.”

2

I weaved around some stacked boxes and a couple of chairs and into the dark end of a foyer where there was light coming from behind a frosted glass door that had the moniker MRS. MARGOT TIMPSON, EDITOR, stenciled on it in black letters.

I tapped gently on the door and a voice that was well practiced at yelling asked me to come in.

Mrs. Timpson was sitting behind her desk and she had pushed back from it in her office chair and was studying me carefully. She had hair too red on the sides and too pink in the thin spots. Her face was eroded with deep canals over which a cheap powder had been caked, like sand over the Sphinx. Her breasts rested comfortably in her lap; they seemed to have recently died and she just hadn’t taken time to dispose of them. I took her age to be somewhere between eighty and around the time of the discovery of fire.

“Sit down,” she said, and her dentures moved when she spoke, as if they might be looking for an escape route.

I took the only chair and looked as intelligent as you might when you’re trying to shake Jim Beam and way too many cold beer chasers.

“You look like you’ve been drinking,” she said.

“Last night. A party.”

“I’ve heard you have a drinking problem.”

“Where would you hear that?”

“From the owner of Fat Billy’s Saloon. He’s my husband. You know, the little shithole just outside of town?”

“I was drinking, but I’m not a drunk.”

“I thought you said it was a party.”

“A party of one. It’s not a habit. I just tied one on a bit. You own a bar, so you know how it is. Now and then, you just drink more than you should.”

“The husband owns the bar,” she said, capturing her teeth with her upper lip as they moved a little too far forward. “He and I are separated. Have been for twenty years. We just never got around to divorcing. We get along all right, long as we don’t live together, or see each other that often, or communicate in any way. But he called and told me about you. He knew you, of course, knew you were trying to get on here at the paper. He said you mentioned it quite a few times between drinks.”

“Guess I was a little nervous.”

“He said you used to play football, quarterback for the Bulldogs. I looked you up. You lost most of your games, didn’t you?”

“But I threw some good passes. I think I have a high school record.”

“No. It got beat two years ago by the Johnson boy. What’s his name? Shit. Can’t think of it. But he beat you. Colored fella.”

I thought to myself: Colored? I hadn’t heard that used in many a moon.

“You were in the service?”

“Signed up for Afghanistan after the towers went down. I was there, but I ended up in Iraq. I kind of felt snookered on that end of the deal.”

“You’re not messed up in the head from being over there, are you?”

“No,” I said, “but the whole thing left me feeling like a cheap date that had been given cab fare and a slap on the ass on the way out the door.”

Timpson twisted her lips, and lined me up with a watery eyeball. “That was humor, right?”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“Just checking.” She swiveled her chair and looked at me from another angle. “I hire you, you don’t have to sit behind a desk all the time, but I like to think you’re working. That your time is my time, and my time is my own. You know this job doesn’t pay much?”

“It’s a start. I can work my way up.”

“Hell, you’re almost at the ceiling now, boy. Thing is, you come from skyscraper material. You had that job in Houston, a Pulitzer nomination. What was it, something about some murder?”

“That’s right. It was luck I was nominated.”

“I was thinking it might have been. Still, you didn’t last in Houston.”

“I came back here for a while, then joined the military.”

“Could there have been a reason you suddenly dropped that job in Houston? What was the problem there?”

“My boss and I didn’t get along.”

“Because you drank?”

“No, ma’am.”

“You know I can call him and ask.”

“You call him, I don’t know he’ll have much to say about the drinking, but whatever he says I doubt any of it will be good, even after several years. He doesn’t like me.”

“You can be straight with me. Nothing you say will embarrass or shock me.”

“I was banging his wife. And his stepdaughter. The daughter, by the way was thirty, the mother forty-eight.”

“No teenagers in the mix?”

“No, ma’am.”

“And I assume your indiscretions do not include the family dog.”

“No, ma’am. I believe you have to draw a line somewhere.”

“You think you’re quite the player, don’t you, boy?”

“I did then.”

Mrs. Timpson pursed her lips. “Go on out there and have Beverly, that’s the receptionist—”

“We met,” I said. “And I believe it’s Belinda.”

“Have her show you your desk. Working for a newspaper is like riding a bicycle or having sex, I suppose. Once you’ve done it, you should be able to do it again. But you can fall off a goddamn bicycle and you can fail to pull out in time when you’re doing the deed. So experience isn’t everything. Use a little common sense.”

“I will.”

“I hope so. Won’t be much in the way of Pulitzer Prize material to write about here, though. Last thing we had in the paper, outside of world news, that was anywhere near exciting was a rabid raccoon down at the Wal-Mart garden center last week. He chased a stock boy around and they had to shoot him.”

“The stock boy or the raccoon?”

“There’s that sense of humor again.”

“Yes, ma’am. And I promise, I’m all done now.”

“Good. I’m putting you on a column. That’s the job you wanted, wasn’t it?”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“Maybe it was a skunk.”

“Beg your pardon?”

“The animal in Wal-Mart. Now that I think about it, it was a skunk, not a raccoon . . . Your column. It’s for the Sunday features. Most of the time you’ll be out of the office, but you got a desk. Still, you’ll report to me regularly. Get a taste today. Leave when you want to. Tomorrow morning, nine sharp, we’ll toss you into the fire.”

I got up and smiled and stuck out my hand to shake. She gave me a dismissive wave of the hand.

I started for the door.

“Varnell Johnson,” she said.

I turned. “Ma’am?”

“That was the colored boy’s name—one that broke your passing record. He could throw like a catapult and run like a goddamn deer.”

From the Hardcover edition.

But the day I arrived back in town there was no evidence of anything wriggling under the surface or anywhere else, unless you count my head, which seemed to be wriggling a lot. I was coming off a lowball drunk and felt as if someone had borrowed my skull to bowl a few frames.

As I drove through Camp Rapture, over the railroad tracks and past the dog food factory, I told myself I would never drink again. But I had told myself that before.

It was a bright day, the sunlight like a burst egg yolk running all over the sidewalk and through the yards, almost snuffing out the grass with its heated glory, and causing everything to be warm and appear fresh, even the houses on the poor side of town from which ancient coats of basic white peeled like stripping sunburn.

I tooled along with my eyes squinted to keep out some of the summer light, eased by Gabby’s veterinarian office and tried not to rubberneck too much, and passed on. I finally drove up to the Camp Rapture Report, got out and stood by my aging car and looked around and hoped maybe this time things were going to go better.

Night before, I had driven over from Houston after leaving Hootie Hoot, Oklahoma, and my crazy Iraq war buddy, Booger, but only got as far as a bar, and later a motel on the outskirts of town, where I drank myself into a stupor in front of the TV set, watching who knows what. For all I cared it could have been a program on tractor repair or how to give yourself a lobotomy.

Next morning, I awoke feeling like something had died in my mouth and something else had crawled up my ass. I showered and brushed the dead thing out of my mouth and decided to live with whatever was up my ass, and drove to my scheduled interview for a possible position on the Camp Rapture Report.

Standing there beside my car, sweating from the late summer heat like a great ape in an argyle sweater, I took in a big breath of hot air. I checked to make sure my zipper was up, then examined the bottoms of my shoes for dog crap, just in case. I went along the sidewalk, strolled past the bee-laden, flowered shrubbery, the smell of which made my stomach roil, and went inside.

The Report looked pretty old-fashioned. Like a place where male reporters ought to wear fedoras with press cards in the hatbands and the female reporters ought to chew gum and talk snappy dialogue through bright red lipstick.

At the front desk I was greeted by a cute blond lady. She smiled and showed me some braces. I think she was in her mid-twenties, possibly even a little older, closer to my age, but the braces and the hairdo, which was too short and not evenly cut, along with a scattering of freckles that decorated her flushed cheeks, made her look like a spunky 1950s schoolkid as seen under a huge magnifying glass.

“Mr. Statler,” she said. “How are you?”

“You remember me?”

“We went to school together.”

“We did?”

“Belinda Hickam. I was a year under you. You were in the journalism club and you wrote for the high school paper. I think you wrote about chess.”

“Actually I only wrote one article about chess.”

“I guess that was the one I read. You’ve been hired to do a column, right?”

“I haven’t been hired yet.”

“Well, I’m going to be optimistic about it. Mrs. Timpson is waiting to see you.”

“Which way?” I said.

She pointed at a foyer where I could see a heap of stacked boxes, advised me to start in that direction and she would buzz Mrs. Timpson that I was on my way back.

“Any advice?” I asked.

“Keep your hands and feet on the visitor’s side of the desk, don’t make any sudden moves, and try not to make direct eye contact.”

2

I weaved around some stacked boxes and a couple of chairs and into the dark end of a foyer where there was light coming from behind a frosted glass door that had the moniker MRS. MARGOT TIMPSON, EDITOR, stenciled on it in black letters.

I tapped gently on the door and a voice that was well practiced at yelling asked me to come in.

Mrs. Timpson was sitting behind her desk and she had pushed back from it in her office chair and was studying me carefully. She had hair too red on the sides and too pink in the thin spots. Her face was eroded with deep canals over which a cheap powder had been caked, like sand over the Sphinx. Her breasts rested comfortably in her lap; they seemed to have recently died and she just hadn’t taken time to dispose of them. I took her age to be somewhere between eighty and around the time of the discovery of fire.

“Sit down,” she said, and her dentures moved when she spoke, as if they might be looking for an escape route.

I took the only chair and looked as intelligent as you might when you’re trying to shake Jim Beam and way too many cold beer chasers.

“You look like you’ve been drinking,” she said.

“Last night. A party.”

“I’ve heard you have a drinking problem.”

“Where would you hear that?”

“From the owner of Fat Billy’s Saloon. He’s my husband. You know, the little shithole just outside of town?”

“I was drinking, but I’m not a drunk.”

“I thought you said it was a party.”

“A party of one. It’s not a habit. I just tied one on a bit. You own a bar, so you know how it is. Now and then, you just drink more than you should.”

“The husband owns the bar,” she said, capturing her teeth with her upper lip as they moved a little too far forward. “He and I are separated. Have been for twenty years. We just never got around to divorcing. We get along all right, long as we don’t live together, or see each other that often, or communicate in any way. But he called and told me about you. He knew you, of course, knew you were trying to get on here at the paper. He said you mentioned it quite a few times between drinks.”

“Guess I was a little nervous.”

“He said you used to play football, quarterback for the Bulldogs. I looked you up. You lost most of your games, didn’t you?”

“But I threw some good passes. I think I have a high school record.”

“No. It got beat two years ago by the Johnson boy. What’s his name? Shit. Can’t think of it. But he beat you. Colored fella.”

I thought to myself: Colored? I hadn’t heard that used in many a moon.

“You were in the service?”

“Signed up for Afghanistan after the towers went down. I was there, but I ended up in Iraq. I kind of felt snookered on that end of the deal.”

“You’re not messed up in the head from being over there, are you?”

“No,” I said, “but the whole thing left me feeling like a cheap date that had been given cab fare and a slap on the ass on the way out the door.”

Timpson twisted her lips, and lined me up with a watery eyeball. “That was humor, right?”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“Just checking.” She swiveled her chair and looked at me from another angle. “I hire you, you don’t have to sit behind a desk all the time, but I like to think you’re working. That your time is my time, and my time is my own. You know this job doesn’t pay much?”

“It’s a start. I can work my way up.”

“Hell, you’re almost at the ceiling now, boy. Thing is, you come from skyscraper material. You had that job in Houston, a Pulitzer nomination. What was it, something about some murder?”

“That’s right. It was luck I was nominated.”

“I was thinking it might have been. Still, you didn’t last in Houston.”

“I came back here for a while, then joined the military.”

“Could there have been a reason you suddenly dropped that job in Houston? What was the problem there?”

“My boss and I didn’t get along.”

“Because you drank?”

“No, ma’am.”

“You know I can call him and ask.”

“You call him, I don’t know he’ll have much to say about the drinking, but whatever he says I doubt any of it will be good, even after several years. He doesn’t like me.”

“You can be straight with me. Nothing you say will embarrass or shock me.”

“I was banging his wife. And his stepdaughter. The daughter, by the way was thirty, the mother forty-eight.”

“No teenagers in the mix?”

“No, ma’am.”

“And I assume your indiscretions do not include the family dog.”

“No, ma’am. I believe you have to draw a line somewhere.”

“You think you’re quite the player, don’t you, boy?”

“I did then.”

Mrs. Timpson pursed her lips. “Go on out there and have Beverly, that’s the receptionist—”

“We met,” I said. “And I believe it’s Belinda.”

“Have her show you your desk. Working for a newspaper is like riding a bicycle or having sex, I suppose. Once you’ve done it, you should be able to do it again. But you can fall off a goddamn bicycle and you can fail to pull out in time when you’re doing the deed. So experience isn’t everything. Use a little common sense.”

“I will.”

“I hope so. Won’t be much in the way of Pulitzer Prize material to write about here, though. Last thing we had in the paper, outside of world news, that was anywhere near exciting was a rabid raccoon down at the Wal-Mart garden center last week. He chased a stock boy around and they had to shoot him.”

“The stock boy or the raccoon?”

“There’s that sense of humor again.”

“Yes, ma’am. And I promise, I’m all done now.”

“Good. I’m putting you on a column. That’s the job you wanted, wasn’t it?”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“Maybe it was a skunk.”

“Beg your pardon?”

“The animal in Wal-Mart. Now that I think about it, it was a skunk, not a raccoon . . . Your column. It’s for the Sunday features. Most of the time you’ll be out of the office, but you got a desk. Still, you’ll report to me regularly. Get a taste today. Leave when you want to. Tomorrow morning, nine sharp, we’ll toss you into the fire.”

I got up and smiled and stuck out my hand to shake. She gave me a dismissive wave of the hand.

I started for the door.

“Varnell Johnson,” she said.

I turned. “Ma’am?”

“That was the colored boy’s name—one that broke your passing record. He could throw like a catapult and run like a goddamn deer.”

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

"There are scenes that stand your hair on end while you fall out of your chair laughing. . . . Be thankful [Lansdale] crafts such wild tall tales."—Chicago Sun-Times"A literary grandson of grizzled '40s writer Jim Thompson (The Grifters) or, say, film director David Lynch in full Blue Velvet mode, the Edgar Award-winning Lansdale writes as if he's just slit his wrists and wants to get the story out before he loses too much blood."—Houston Chronicle“Superb.... Reading Lansdale is like riding the best tilt-a-whirl you’ve ever been on.”—TheWashington Post"Mysteries usually begin with a drop of blood and end up with a barrel full. But Mr. Lansdale, who resides in Nacogdoches, tells this one Texas-style. . . . It's a puzzle, a game, a carnival act of murder and mayhem."—Dallas Morning News"Lansdale has created a landscape of broken dreams, skewed personalities and hope still clinging to the inside of the Pandora's box of problems they all share. . . . He has been called a folklorist, and Leather Maiden makes you want to sit on a porch listening to him spin a yarn that you know doesn't contain a true sentence."—Los Angeles Times"Hilariously alarming. . . . a bruising jolt from an immoral moralist."—Austin Chronicle "[T]he combination of back-porch storytelling and breakneck suspense . . . makes Leather Maiden a must-read for thriller fans."—Texas Monthly"Lansdale writes about the poor, emotionally traumatized, violent and stoically heroic better than almost anyone.”—The Marin Independent Journal"Joe Lansdale has won both domestic and international awards for his past mystery novels, but he's never written one quite like his new volume Leather Maiden. . . . Some of the conversations here are hilarious, even if the language is anything but politically correct. Cason Statler is working in Texas small towns and country communities, where folks don't mince words, and often aren't shy about expressing disdain and wallowing in stereotypes. These ingredients only add more punch and sparkle to a tremendous work that deftly blends farce and dry wit with adventure and crime solving."-—The (Nashville) City Paper"Black humor and bad taste abound in Lansdale's Edgar-winning body of work, and the cult author's newest literary thriller--about Casey Stanton, a hard-drinking, Pulitzer-winning journalist (and Gulf War vet) who returns to his rural Texas hometown after losing his job in spectacular fashion--is no exception. As he investigates a cold-case murder for the local paper and stalks his ex, Stanton emerges as an appealingly ripe hayseed Sam Spade."—Details "With its mysterious disappearances, abandoned houses, midnight trysts, and hidden culverts, Lansdale's latest is a contemporary Hardy Boys story on crank, read to best advantage late at night under the covers, with the aid of a flashlight."—Library Journal“If Mark Twain had written for the Grand Guignol he'd have come up with something like this. Like all Lansdale's books, Leather Maiden walks a delicate line between grotesquerie and moral outrage all the while managing to be funnier than anything I've read all year.”—Scott Phillips, author of Cottonwood“Not since Dexter's The Paperboy has a novel blown me to hell and back. A stunning game of blackmail, murder, manipulation propel Joe into a league that includes one . . . himself. This is the novel of the year, the essence of what mystery aspires to be. It is truly jaw dropping.”—Ken Bruen, author of Priest “Leather Maiden is gripping, ferocious, and very funny. If you have not yet sampled Joe Lansdale’s singular, twisted brand of genius, this is a good place to start.”—George Pelecanos, author of The Turnaround