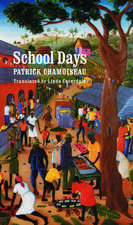

Leaving Tangier

Autor Tahar Ben Jelloun Traducere de Linda Coverdaleen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mar 2009 – vârsta de la 18 ani

From one of the world's great writers, a breakthrough novel about leaving home for a better life

In his new novel, award-winning, internationally bestselling author Tahar Ben Jelloun tells the story of a Moroccan brother and sister making new lives for themselves in Spain. Azel is a young man in Tangier who dreams of crossing the Strait of Gibraltar. When he meets Miguel, a wealthy Spaniard, he leaves behind his girlfriend, his sister, Kenza, and his mother, and moves with him to Barcelona, where Kenza eventually joins them. What they find there forms the heart of this novel of seduction and betrayal, deception and disillusionment, in which Azel and Kenza are reminded powerfully not only of where they've come from, but also of who they really are.

In his new novel, award-winning, internationally bestselling author Tahar Ben Jelloun tells the story of a Moroccan brother and sister making new lives for themselves in Spain. Azel is a young man in Tangier who dreams of crossing the Strait of Gibraltar. When he meets Miguel, a wealthy Spaniard, he leaves behind his girlfriend, his sister, Kenza, and his mother, and moves with him to Barcelona, where Kenza eventually joins them. What they find there forms the heart of this novel of seduction and betrayal, deception and disillusionment, in which Azel and Kenza are reminded powerfully not only of where they've come from, but also of who they really are.

Preț: 80.43 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 121

Preț estimativ în valută:

15.39€ • 16.01$ • 12.71£

15.39€ • 16.01$ • 12.71£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 24 martie-07 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780143114659

ISBN-10: 0143114654

Pagini: 275

Dimensiuni: 127 x 178 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: Penguin Books

ISBN-10: 0143114654

Pagini: 275

Dimensiuni: 127 x 178 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: Penguin Books

Recenzii

"A brave, unflinching look at the issues underlying economic migration from North Africa-and the hard choices people make between roots and wings."

-The Economist

"[A] penetrating tale."

-The New York Times Book Review

"Ben Jelloun is arguably Morocco's greatest living author, whose impressive body of work combines intellect and imagination in magical fusion. . . . Leaving Tangier is a wholly original feat of form and imagination. . . . There is unexpected humour jostling alongside the horror, in magical-realist passages illuminating the clash of traditional and modern."

-The Guardian

"Artful and compassionate, Leaving Tangier evokes a milieu of self-exile and great expectations."

-The Washington Post

"Just as John Updike reminded Americans of the guilt and vertigo they sort out between the sheets, Ben Jelloun has chronicled the shame and secrecy surrounding sex in a Morocco of creeping fundamentalism and diminishing opportunity. The explicitness of the sex in his work is powerful and often beautifully erotic; it's . . . where sex amplifies the degradations of postcolonial economic reality that Leaving Tangier lands like a hammer blow. . . . Leaving Tangier would read like a blunt political instrument . . . were Ben Jelloun not such a wonderfully specific writer. Many scenes of agonizing depravity convey the desperation of poverty. . . . From such bracing particulars, Ben Jelloun fashions political fiction of great urgency."

-John Freeman, Bookforum

"Tahar Ben Jelloun lifts the veil on an astounding world of a thousand and one nights."

-Le Point

"Of the thirty books Tahar Ben Jelloun has written, this is undoubtedly one of the most courageous."

-Le Monde des Livres

-The Economist

"[A] penetrating tale."

-The New York Times Book Review

"Ben Jelloun is arguably Morocco's greatest living author, whose impressive body of work combines intellect and imagination in magical fusion. . . . Leaving Tangier is a wholly original feat of form and imagination. . . . There is unexpected humour jostling alongside the horror, in magical-realist passages illuminating the clash of traditional and modern."

-The Guardian

"Artful and compassionate, Leaving Tangier evokes a milieu of self-exile and great expectations."

-The Washington Post

"Just as John Updike reminded Americans of the guilt and vertigo they sort out between the sheets, Ben Jelloun has chronicled the shame and secrecy surrounding sex in a Morocco of creeping fundamentalism and diminishing opportunity. The explicitness of the sex in his work is powerful and often beautifully erotic; it's . . . where sex amplifies the degradations of postcolonial economic reality that Leaving Tangier lands like a hammer blow. . . . Leaving Tangier would read like a blunt political instrument . . . were Ben Jelloun not such a wonderfully specific writer. Many scenes of agonizing depravity convey the desperation of poverty. . . . From such bracing particulars, Ben Jelloun fashions political fiction of great urgency."

-John Freeman, Bookforum

"Tahar Ben Jelloun lifts the veil on an astounding world of a thousand and one nights."

-Le Point

"Of the thirty books Tahar Ben Jelloun has written, this is undoubtedly one of the most courageous."

-Le Monde des Livres

Notă biografică

Tahar Ben Jelloun was born in 1944 in Fez, Morocco, and emigrated to France in 1961. A novelist, essayist, critic, and poet, he is a regular contributor to Le Monde, La Republica, El País, and Panorama. His novels include The Sacred Night (winner of the 1987 Prix Goncourt), Corruption, and The Last Friend. Ben Jelloun won the 1994 Prix Maghreb, and in 2004 he won the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award for This Blinding Absence of Light.

Extras

1

Toutia

In Tangier, in the winter, the Café Hafa becomes an observatory for dreams and their aftermath. Cats from the cemetery, the terraces, and the chief communal bread oven of the Marshan district gather round the café as if to watch the play unfolding there in silence, and fooling nobody. Long pipes of kif pass from table to table while glasses of mint tea grow cold, enticing bees that eventually tumble in, a matter of indifference to customers long since lost to the limbo of hashish and tinseled reverie. In the back of one room, two men meticulously prepare the key that opens the gates of departure, selecting leaves, then chopping them swiftly and efficiently. Neither man looks up. Leaning back against the wall, customers sit on mats and stare at the horizon as if seeking to read their fate. They look at the sea, at the clouds that blend into the mountains, and they wait for the twinkling lights of Spain to appear. They watch them without seeing them, and sometimes, even when the lights are lost in fog and bad weather, they see them anyway.

Everyone is silent. Everyone listens. Perhaps she will show up this evening. She’ll talk to them, sing them the song of the drowned man who became a sea star suspended over the straits. They have agreed never to speak her name: that would destroy her, and provoke a whole series of misfortunes as well. So the men watch one another and say nothing. Each one enters his dream and clenches his fists. Only the waiters and the tea master, who owns the café, remain outside the circle, preparing and serving their fare with discretion, coming and going from terrace to terrace without disturbing anyone’s dream. The customers know one another but do not converse. Most of them come from the same neighborhood and have just enough to pay for the tea and a few pipes of kif. Some have a slate on which they keep track of their debt. As if by agreement, they keep silent. Especially at this hour and at this delicate moment when their whole being is caught up in the distance, studying the slightest ripple of the waves or the sound of an old boat coming home to the harbor. Sometimes, hearing the echo of a cry for help, they look at one another without turning a hair.

Yes, she might appear, and reveal a few of her secrets. Conditions are favorable: a clear, almost white sky, reflected in a limpid sea transformed into a pool of light. Silence in the café; silence on all faces. Perhaps the precious moment has arrived . . . at last she will speak!

Occasionally the men do allude to her, especially when the sea has tossed up the bodies of a few drowned souls. She has acquired more riches, they say, and surely owes us a favor! They have nicknamed her Toutia, a word that means nothing, but to them she is a spider that can feast on human flesh yet will sometimes tell them, in the guise of a beneficent voice, that tonight is not the night, that they must put off their voyage for a while.

Like children, they believe in this story that comforts them and lulls them to sleep as they lean back against the rough wall. In the tall glasses of cold tea, the green mint has been tarnished black. The bees have all drowned at the bottom. The men no longer sip this tea now steeped into bitterness. With a spoon they fish the bees out one by one, laying them on the table and exclaiming, “Poor little drowned things, victims of their own greediness!”

As in an absurd and persistent dream, Azel sees his naked body among other naked bodies swollen by seawater, his face distorted by salt and longing, his skin burnt by the sun, split open across the chest as if there had been fighting before the boat went down. Azel sees his body more and more clearly, in a blue and white fishing boat heading ever so slowly to the center of the sea, for Azel has decided that this sea has a center and that this center is a green circle, a cemetery where the current catches hold of corpses, taking them to the bottom to place them on a bank of seaweed. He knows that there, in this specific circle, a fluid boundary exists, a kind of separation between the sea and the ocean, the calm, smooth waters of the Mediterranean and the fierce surge of the Atlantic. He holds his nose, because staring so hard at these images has filled his nostrils with the odor of death, a suffocating, clinging, nauseating stench. When he closes his eyes, death begins to dance around the table where he sits almost every day to watch the sunset and count the first lights scintillating across the way, on the coast of Spain. His friends join him, to play cards in silence. Even if some of them share his obsession of leaving the country someday, they know, having heard it one night in Toutia’s voice, that they must not lose themselves in images that foster sadness.

Azel says not a word about either his plan or his dream. People sense that he is unhappy, on edge, and they say he is bewitched by love for a married woman. They believe he has flings with foreign women and suspect that he wants their help to leave Morocco. He denies this, of course, preferring to laugh about it. But the idea of sailing away, of mounting a green-painted horse and crossing the sea of the straits, that idea of becoming a transparent shadow visible only by day, an image scudding at top speed across the waves—that idea never leaves him now. He keeps it to himself, doesn’t mention it to his sister, Kenza, still less to his mother, who worries because he is losing weight and smoking too much.

Even Azel has come to believe in the story of she who will appear and help them to cross, one by one, that distance separating them from life, the good life, or death.

Toutia

In Tangier, in the winter, the Café Hafa becomes an observatory for dreams and their aftermath. Cats from the cemetery, the terraces, and the chief communal bread oven of the Marshan district gather round the café as if to watch the play unfolding there in silence, and fooling nobody. Long pipes of kif pass from table to table while glasses of mint tea grow cold, enticing bees that eventually tumble in, a matter of indifference to customers long since lost to the limbo of hashish and tinseled reverie. In the back of one room, two men meticulously prepare the key that opens the gates of departure, selecting leaves, then chopping them swiftly and efficiently. Neither man looks up. Leaning back against the wall, customers sit on mats and stare at the horizon as if seeking to read their fate. They look at the sea, at the clouds that blend into the mountains, and they wait for the twinkling lights of Spain to appear. They watch them without seeing them, and sometimes, even when the lights are lost in fog and bad weather, they see them anyway.

Everyone is silent. Everyone listens. Perhaps she will show up this evening. She’ll talk to them, sing them the song of the drowned man who became a sea star suspended over the straits. They have agreed never to speak her name: that would destroy her, and provoke a whole series of misfortunes as well. So the men watch one another and say nothing. Each one enters his dream and clenches his fists. Only the waiters and the tea master, who owns the café, remain outside the circle, preparing and serving their fare with discretion, coming and going from terrace to terrace without disturbing anyone’s dream. The customers know one another but do not converse. Most of them come from the same neighborhood and have just enough to pay for the tea and a few pipes of kif. Some have a slate on which they keep track of their debt. As if by agreement, they keep silent. Especially at this hour and at this delicate moment when their whole being is caught up in the distance, studying the slightest ripple of the waves or the sound of an old boat coming home to the harbor. Sometimes, hearing the echo of a cry for help, they look at one another without turning a hair.

Yes, she might appear, and reveal a few of her secrets. Conditions are favorable: a clear, almost white sky, reflected in a limpid sea transformed into a pool of light. Silence in the café; silence on all faces. Perhaps the precious moment has arrived . . . at last she will speak!

Occasionally the men do allude to her, especially when the sea has tossed up the bodies of a few drowned souls. She has acquired more riches, they say, and surely owes us a favor! They have nicknamed her Toutia, a word that means nothing, but to them she is a spider that can feast on human flesh yet will sometimes tell them, in the guise of a beneficent voice, that tonight is not the night, that they must put off their voyage for a while.

Like children, they believe in this story that comforts them and lulls them to sleep as they lean back against the rough wall. In the tall glasses of cold tea, the green mint has been tarnished black. The bees have all drowned at the bottom. The men no longer sip this tea now steeped into bitterness. With a spoon they fish the bees out one by one, laying them on the table and exclaiming, “Poor little drowned things, victims of their own greediness!”

As in an absurd and persistent dream, Azel sees his naked body among other naked bodies swollen by seawater, his face distorted by salt and longing, his skin burnt by the sun, split open across the chest as if there had been fighting before the boat went down. Azel sees his body more and more clearly, in a blue and white fishing boat heading ever so slowly to the center of the sea, for Azel has decided that this sea has a center and that this center is a green circle, a cemetery where the current catches hold of corpses, taking them to the bottom to place them on a bank of seaweed. He knows that there, in this specific circle, a fluid boundary exists, a kind of separation between the sea and the ocean, the calm, smooth waters of the Mediterranean and the fierce surge of the Atlantic. He holds his nose, because staring so hard at these images has filled his nostrils with the odor of death, a suffocating, clinging, nauseating stench. When he closes his eyes, death begins to dance around the table where he sits almost every day to watch the sunset and count the first lights scintillating across the way, on the coast of Spain. His friends join him, to play cards in silence. Even if some of them share his obsession of leaving the country someday, they know, having heard it one night in Toutia’s voice, that they must not lose themselves in images that foster sadness.

Azel says not a word about either his plan or his dream. People sense that he is unhappy, on edge, and they say he is bewitched by love for a married woman. They believe he has flings with foreign women and suspect that he wants their help to leave Morocco. He denies this, of course, preferring to laugh about it. But the idea of sailing away, of mounting a green-painted horse and crossing the sea of the straits, that idea of becoming a transparent shadow visible only by day, an image scudding at top speed across the waves—that idea never leaves him now. He keeps it to himself, doesn’t mention it to his sister, Kenza, still less to his mother, who worries because he is losing weight and smoking too much.

Even Azel has come to believe in the story of she who will appear and help them to cross, one by one, that distance separating them from life, the good life, or death.