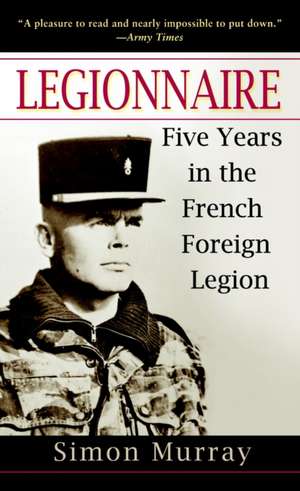

Legionnaire: Five Years in the French Foreign Legion

Autor Simon Murrayen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 apr 2006

–Army Times

“Embodies an experience that many have enjoyed in fantasy–few in reality.”

–The Washington Post

The French Foreign Legion–mysterious, romantic, deadly–is filled with men of dubious character, and hardly the place for a proper Englishman just nineteen years of age. Yet in 1960, Simon Murray traveled alone to Paris, Marseilles, and ultimately Algeria to fulfill the toughest contract of his life: a five-year stint in the Legion. Along the way, he kept a diary.

Legionnaire is a compelling, firsthand account of Murray’s experience with this legendary band of soldiers. This gripping journal offers stark evidence that the Legion’s reputation for pushing men to their breaking points and beyond is well deserved. In the fierce, sun-baked North African desert, strong men cracked under brutal officers, merciless training methods, and barbarous punishments. Yet Murray survived, even thrived. For he shared one trait with these hard men from all nations and backgrounds: a determination never to surrender.

“The drama, excitement, and color of a good guts-and-glory thriller.”

–Dr. Henry Kissinger

Preț: 51.10 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 77

Preț estimativ în valută:

9.78€ • 10.17$ • 8.07£

9.78€ • 10.17$ • 8.07£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780891418870

ISBN-10: 0891418873

Pagini: 348

Dimensiuni: 108 x 175 x 27 mm

Greutate: 0.19 kg

Editura: Presidio Press

ISBN-10: 0891418873

Pagini: 348

Dimensiuni: 108 x 175 x 27 mm

Greutate: 0.19 kg

Editura: Presidio Press

Extras

PART ONE

Incubation

22 February 1960 - Paris

I was awake long before the dawn, and by the time there was a grayness in the sky I had finally made up my mind to go. By eight o'clock I was in the Métro heading for the Old Fort at Vincennes--the recruitment center of the Foreign Legion. There were few people about, and those who were had grim Monday-morning faces, probably reflecting my own.

From Vincennes station I walked through the streets and eventually arrived at the massive gates of the Old Fort. On a plaque on the wall there was a simple notice:

bureau d'engagement - légion étrangére - ouvert jour et nuit.

I hammered on the huge doors, which swung open in response, and stepped into a cobbled courtyard to be confronted by the first legionnaire I had ever seen. He was dressed in khaki with a blue cummerbund around his waist and bright red epaulettes on his shoulders. He wore a white kepi on his head and had white gaiters, and I thought he looked quite impressive. I was less impressed with the archaic-looking rifle at his side. He slammed the great doors shut and beckoned me with his head to follow him.

I was ushered into a room on the door of which was inscribed bureau de semaine, which I assumed meant General Office or something similar. It was a primitive enough chamber with a bare plank floor and a wooden table and chair. One or two old and tired-looking photographs depicting legionnaires holding the regimental colors, men driving tanks through the desert, and others marching down the Champs-Élysées hung limply on the wall.

A sergeant sitting behind the table looked me up and down but said nothing. I broke the ice and said in English that I had come to join the Foreign Legion, and he gave me a look that was a mixture of wonder and sympathy. He spoke reasonable English with a German accent and asked me "Why?"

I said something conventional about adventure and so on, and he said I had come to the wrong place. He said five years in the Legion would be long and hard, that I should forget the romantic idea that the English have of the Legion, and that I would do well to go away and reconsider the whole thing. I said I had given it a lot of thought and had come a long way, and eventually he said "Okay" with a sigh and led me upstairs and into an assembly hall.

As I walked into the hall, I was confronted with about forty people sitting on benches around the walls. Eighty eyes immediately focused on me, and my own swiveled round the room in a flash. There was not one single face on which my eyes could come to rest and l could say "He is like me" or "We are the same in some way." I knew instantly that I had not the slightest thing in common with any one of them.

I took an empty place at the end of one of the benches and contemplated my feet, but I could feel them all staring at me. They were an incredible mixture, dark, gray, white, brown, beards, moustaches, bald, and shaggy, wearing an unlimited array of different garments, but they all looked tough and unkempt and totally different from me. I was wishing to hell that I had worn a pair of jeans and an old pullover instead of a three-piece suit with a double-breasted waistcoat, of all things.

A couple of them were snickering on the other side of the room, and l kept my eyes averted although I could feel myself getting hot. We sat for a long time until at last an officer arrived with a couple of men in white coats, and we were told to strip down to underpants.

One by one we were called forward and given a series of medical tests. This took two hours, and after it was over we were again left sitting on our benches. The medical tests had loosened a few tongues, and people were chatting away to each other in different languages, mostly German. I kept to myself at this point and was wondering whether I would be in time to catch the six o'clock flight from Orly back to London.

An hour passed, and the officer reappeared accompanied by the sergeant who had been in the Bureau de Semaine. He made an announcement in French, from which I gathered that they had need of only seven of us and the rest could go. They read out seven names and mine was one of them.

The seven of us were called forward and led out of the room, leaving behind the rest who were being herded up for departure back into the welcome arms of Paris. We were taken along a series of dark passages and up several flights of stone stairs to a supply room at the top of the old building, where we were handed battledress and trousers, a pair of boots, and a greatcoat. Then we were given some food in a dingy little room that had metal tables and stools.

Nobody spoke a word during the meal, and when it was over we were ushered into a small room and made to listen to a tape recording, repeated in several languages. In the room there was a single naked forty-watt bulb dangling from the ceiling on a long cord, and the atmosphere was sinister. With me were two Germans, a Spaniard, a Belgian, and two Dutchmen. Everybody was tense.

The tape played in English, and I was informed that I was about to sign a five-year contract and that when l had signed there could be no turning back. The voice that came over the loudspeaker was solemn and had all the gloom of a judge pronouncing sentence of death. I wanted to talk to it, I wanted to talk to anybody who was English, but it was a one-way dialogue and it was decision-making time. We listened in silence and nobody said anything, nobody started shouting to get out, nobody cracked or lost their nerve or gave way to rising panic. Then we filed through into an office one at a time and signed the contract. It comprised three enormous tomes of unintelligible French. Attempts to read it were discouraged and would have been pointless, anyway.

I feel as though I have signed a blank check over to a complete stranger. Night has fallen and we are in a dormitory. Metal beds with straw-filled mattresses and a blanket. A bugle sounds "lights out" in the night, faint and loud against the mood of the wind. It is the end of my first day and the beginning of a new adventure. I think that the sergeant was right; it will be a long road and a lonely one. I am in the heart of Paris but it feels like the mountains of the moon.

The Next Day

We were awakened early with a bouncy bugle shattering cozy sleep, and after a cold-water rinse and a mug of coffee we were put to peeling potatoes, sweeping floors, and other general chores, called corvée, around the fort. There is very little talk, primarily due to the language problem. The day passed quickly and tonight we are catching the train to Marseille. The journey begins.

24 February 1960

There was trouble on the train last night and I have already made an enemy. There were not enough seats and it was first come, first served. During the evening I left the compartment for a pee and returned to find that the Spaniard had pinched my seat. I didn't like this situation at all. I tried very slowly to get across to him that he was in my seat and reading my magazine, but he affected deafness. It was early days to be getting into fights, but it was even earlier to be running away from them, and I knew quite suddenly that I would have to make a stand.

In one move, before I had time to talk myself out of it, I grabbed him by the lapels, yanked him to his feet, and threw him the length of the carriage.

We were both quite surprised: he by being thrown so violently and me by throwing him. I am quite small and am not used to throwing people about!

However, his surprise quickly gave in to other emotions, and he came charging at me. Our greatcoats and the lack of space hampered active movement, and neither of us got the better of the other, but I think I gave a good account of myself. Eventually the others in the carriage got bored with it and we were dragged apart. Public opinion came down on my side and the Spaniard was shoved out of the compartment back into the corridor. He went out with wild eyes glaring at me, screaming Spanish oaths and what were obviously threats of vengeance. I shall have to watch him.

We arrived in Marseille in midmorning and were driven in trucks to a fort overlooking the port. The fort is called Saint Nicolas. There are some three hundred Legion recruits here, and they arrive in batches of about thirty a day from the various recruitment centers at Strasbourg, Lyon, and Paris. About half are shipped to Algeria every ten days or so.

The first move was to issue us with denims in exchange for our battledress uniforms. The denims are dirty and torn, without buttons, held together with bits of string. Obviously the other gear was just for the train journey and for the benefit of the general public so that they would not feel they were traveling with convicts, because that is now what we look like.

The central courtyard of the fort looks exactly like the kind of prison compound that one sees in movies; groups cluster together looking furtive, others sit on the ground leaning against the wall, somehow everybody is whispering--or is it that I can't understand what they are saying? The NCOs look tough and they probably are. Why the hell do they look like prison wardens?

The atmosphere inside the barracks is cold and gloomy. The sanitary conditions are unbelievable. In a room that looks like an empty horse stable on a winter's morning, there is a solitary tap protruding from the wall, under which there is a sort of trough. The tap runs icy water, there is no window and no light, and this is the washroom for a hundred men. The lavatories are holes in the ground with footstands each side. Looks like a bad place for backache. In the dormitories the bunks are three-high, with the width of a man's body between them both vertically and horizontally. It reminds me of a concentration camp I once visited in Belgium that had been preserved as a macabre reminder of the Holocaust. The food by contrast is good, if you can get it. The emphasis is on first come, first served, and it is a self-service operation with no limits.

It is the evening and I am lying on my bunk with people all around. I am totally unnoticed, which is comforting. Card games are in progress around the tables in the center of the room; the whole place is a complete fog of smoke, and the sound is a perpetual jangle of different tongues jabbering in a million languages, none of which I understand.

Outside it's raining and the wind is blowing hard. Earlier this evening l walked along the battlements of the fort, which overlooks the harbor. One can see the Count of Monte Cristo's Chateau d'If, and I think I know how he felt. Strange sensations and emotions hit me as I looked at the beckoning lights of Marseille's nightlife. The boats idling on their moorings waiting for the summer sun looked tempting.

It seems impossible to believe that I have been here for only one day. I feel much more a prisoner than a soldier. I really have cut the old lifeline this time: This is a long way from home and a long way from anything I have ever known. To think, if things had gone the way they nearly did and fate had played a different card, I would probably have gone into the British army, been commissioned like my brother Anthony in the Scots Greys, and now be in a very different situation. I don't feel lonely but I feel cut off, totally disconnected from my own people. That's a bit frightening somehow. I could go down the plughole tomorrow and there's not a single person here who would turn a hair.

It's going to be a long time before I see my friends again, or drink a pint, or go to the National, or play cricket. Didsbury Cricket Club will be in a terrible state next weekend without me. Anyway, I suppose I'll get used to it. They say one gets used to anything in time. What the sages do not say is how much time.

Ten Days Later

Several days have gone quickly by. Each one begins at six o'clock with an assembly on the fort battlements. We stand in the cold in our thin denims and respond with a yell of "ici" when our names are called, and then we are dispatched in small groups on corvée. I have been working at a sawmill for the last few days, during which it hasn't stopped raining--freezing hands fumbling with logs, soaking wet denims, blue with cold. Come on Africa!

11 March 1960

There are a lot of Germans here, with Spaniards and Italians not far behind in numbers. The Italians spend much of their time buying and selling odds and ends or exchanging foreign currencies; God knows why, there's little enough money around. They are born brokers but light on credibility. I have struck up a talking relationship with an English-speaking Dutchman called Hank. He's in bad shape, having run off and left his wife after a family row and he's now regretting it. He has asked to be released, but it is doubtful if they will let him go because it would open the floodgates to all the others who must have changed their minds by now.

There is also an Australian swagman here, and it is good to have somebody who speaks more or less the same language. His name is Treers and three years in the merchant navy as a deckhand and several doses of clap are his chief claim to fame and the core of his conversation.

A Canadian called Gagnon arrived a couple of days after Treers, and he also claims to have had a long and distinguished career in the Canadian navy, but as an officer! Treers doesn't believe it--I can see why--and they are on a collision course. Gagnon is oily and unpleasant material. He brought with him two suitcases full of kit and ingratiated himself by distributing it among the parasites. The brokers could hardly believe their eyes.

Incubation

22 February 1960 - Paris

I was awake long before the dawn, and by the time there was a grayness in the sky I had finally made up my mind to go. By eight o'clock I was in the Métro heading for the Old Fort at Vincennes--the recruitment center of the Foreign Legion. There were few people about, and those who were had grim Monday-morning faces, probably reflecting my own.

From Vincennes station I walked through the streets and eventually arrived at the massive gates of the Old Fort. On a plaque on the wall there was a simple notice:

bureau d'engagement - légion étrangére - ouvert jour et nuit.

I hammered on the huge doors, which swung open in response, and stepped into a cobbled courtyard to be confronted by the first legionnaire I had ever seen. He was dressed in khaki with a blue cummerbund around his waist and bright red epaulettes on his shoulders. He wore a white kepi on his head and had white gaiters, and I thought he looked quite impressive. I was less impressed with the archaic-looking rifle at his side. He slammed the great doors shut and beckoned me with his head to follow him.

I was ushered into a room on the door of which was inscribed bureau de semaine, which I assumed meant General Office or something similar. It was a primitive enough chamber with a bare plank floor and a wooden table and chair. One or two old and tired-looking photographs depicting legionnaires holding the regimental colors, men driving tanks through the desert, and others marching down the Champs-Élysées hung limply on the wall.

A sergeant sitting behind the table looked me up and down but said nothing. I broke the ice and said in English that I had come to join the Foreign Legion, and he gave me a look that was a mixture of wonder and sympathy. He spoke reasonable English with a German accent and asked me "Why?"

I said something conventional about adventure and so on, and he said I had come to the wrong place. He said five years in the Legion would be long and hard, that I should forget the romantic idea that the English have of the Legion, and that I would do well to go away and reconsider the whole thing. I said I had given it a lot of thought and had come a long way, and eventually he said "Okay" with a sigh and led me upstairs and into an assembly hall.

As I walked into the hall, I was confronted with about forty people sitting on benches around the walls. Eighty eyes immediately focused on me, and my own swiveled round the room in a flash. There was not one single face on which my eyes could come to rest and l could say "He is like me" or "We are the same in some way." I knew instantly that I had not the slightest thing in common with any one of them.

I took an empty place at the end of one of the benches and contemplated my feet, but I could feel them all staring at me. They were an incredible mixture, dark, gray, white, brown, beards, moustaches, bald, and shaggy, wearing an unlimited array of different garments, but they all looked tough and unkempt and totally different from me. I was wishing to hell that I had worn a pair of jeans and an old pullover instead of a three-piece suit with a double-breasted waistcoat, of all things.

A couple of them were snickering on the other side of the room, and l kept my eyes averted although I could feel myself getting hot. We sat for a long time until at last an officer arrived with a couple of men in white coats, and we were told to strip down to underpants.

One by one we were called forward and given a series of medical tests. This took two hours, and after it was over we were again left sitting on our benches. The medical tests had loosened a few tongues, and people were chatting away to each other in different languages, mostly German. I kept to myself at this point and was wondering whether I would be in time to catch the six o'clock flight from Orly back to London.

An hour passed, and the officer reappeared accompanied by the sergeant who had been in the Bureau de Semaine. He made an announcement in French, from which I gathered that they had need of only seven of us and the rest could go. They read out seven names and mine was one of them.

The seven of us were called forward and led out of the room, leaving behind the rest who were being herded up for departure back into the welcome arms of Paris. We were taken along a series of dark passages and up several flights of stone stairs to a supply room at the top of the old building, where we were handed battledress and trousers, a pair of boots, and a greatcoat. Then we were given some food in a dingy little room that had metal tables and stools.

Nobody spoke a word during the meal, and when it was over we were ushered into a small room and made to listen to a tape recording, repeated in several languages. In the room there was a single naked forty-watt bulb dangling from the ceiling on a long cord, and the atmosphere was sinister. With me were two Germans, a Spaniard, a Belgian, and two Dutchmen. Everybody was tense.

The tape played in English, and I was informed that I was about to sign a five-year contract and that when l had signed there could be no turning back. The voice that came over the loudspeaker was solemn and had all the gloom of a judge pronouncing sentence of death. I wanted to talk to it, I wanted to talk to anybody who was English, but it was a one-way dialogue and it was decision-making time. We listened in silence and nobody said anything, nobody started shouting to get out, nobody cracked or lost their nerve or gave way to rising panic. Then we filed through into an office one at a time and signed the contract. It comprised three enormous tomes of unintelligible French. Attempts to read it were discouraged and would have been pointless, anyway.

I feel as though I have signed a blank check over to a complete stranger. Night has fallen and we are in a dormitory. Metal beds with straw-filled mattresses and a blanket. A bugle sounds "lights out" in the night, faint and loud against the mood of the wind. It is the end of my first day and the beginning of a new adventure. I think that the sergeant was right; it will be a long road and a lonely one. I am in the heart of Paris but it feels like the mountains of the moon.

The Next Day

We were awakened early with a bouncy bugle shattering cozy sleep, and after a cold-water rinse and a mug of coffee we were put to peeling potatoes, sweeping floors, and other general chores, called corvée, around the fort. There is very little talk, primarily due to the language problem. The day passed quickly and tonight we are catching the train to Marseille. The journey begins.

24 February 1960

There was trouble on the train last night and I have already made an enemy. There were not enough seats and it was first come, first served. During the evening I left the compartment for a pee and returned to find that the Spaniard had pinched my seat. I didn't like this situation at all. I tried very slowly to get across to him that he was in my seat and reading my magazine, but he affected deafness. It was early days to be getting into fights, but it was even earlier to be running away from them, and I knew quite suddenly that I would have to make a stand.

In one move, before I had time to talk myself out of it, I grabbed him by the lapels, yanked him to his feet, and threw him the length of the carriage.

We were both quite surprised: he by being thrown so violently and me by throwing him. I am quite small and am not used to throwing people about!

However, his surprise quickly gave in to other emotions, and he came charging at me. Our greatcoats and the lack of space hampered active movement, and neither of us got the better of the other, but I think I gave a good account of myself. Eventually the others in the carriage got bored with it and we were dragged apart. Public opinion came down on my side and the Spaniard was shoved out of the compartment back into the corridor. He went out with wild eyes glaring at me, screaming Spanish oaths and what were obviously threats of vengeance. I shall have to watch him.

We arrived in Marseille in midmorning and were driven in trucks to a fort overlooking the port. The fort is called Saint Nicolas. There are some three hundred Legion recruits here, and they arrive in batches of about thirty a day from the various recruitment centers at Strasbourg, Lyon, and Paris. About half are shipped to Algeria every ten days or so.

The first move was to issue us with denims in exchange for our battledress uniforms. The denims are dirty and torn, without buttons, held together with bits of string. Obviously the other gear was just for the train journey and for the benefit of the general public so that they would not feel they were traveling with convicts, because that is now what we look like.

The central courtyard of the fort looks exactly like the kind of prison compound that one sees in movies; groups cluster together looking furtive, others sit on the ground leaning against the wall, somehow everybody is whispering--or is it that I can't understand what they are saying? The NCOs look tough and they probably are. Why the hell do they look like prison wardens?

The atmosphere inside the barracks is cold and gloomy. The sanitary conditions are unbelievable. In a room that looks like an empty horse stable on a winter's morning, there is a solitary tap protruding from the wall, under which there is a sort of trough. The tap runs icy water, there is no window and no light, and this is the washroom for a hundred men. The lavatories are holes in the ground with footstands each side. Looks like a bad place for backache. In the dormitories the bunks are three-high, with the width of a man's body between them both vertically and horizontally. It reminds me of a concentration camp I once visited in Belgium that had been preserved as a macabre reminder of the Holocaust. The food by contrast is good, if you can get it. The emphasis is on first come, first served, and it is a self-service operation with no limits.

It is the evening and I am lying on my bunk with people all around. I am totally unnoticed, which is comforting. Card games are in progress around the tables in the center of the room; the whole place is a complete fog of smoke, and the sound is a perpetual jangle of different tongues jabbering in a million languages, none of which I understand.

Outside it's raining and the wind is blowing hard. Earlier this evening l walked along the battlements of the fort, which overlooks the harbor. One can see the Count of Monte Cristo's Chateau d'If, and I think I know how he felt. Strange sensations and emotions hit me as I looked at the beckoning lights of Marseille's nightlife. The boats idling on their moorings waiting for the summer sun looked tempting.

It seems impossible to believe that I have been here for only one day. I feel much more a prisoner than a soldier. I really have cut the old lifeline this time: This is a long way from home and a long way from anything I have ever known. To think, if things had gone the way they nearly did and fate had played a different card, I would probably have gone into the British army, been commissioned like my brother Anthony in the Scots Greys, and now be in a very different situation. I don't feel lonely but I feel cut off, totally disconnected from my own people. That's a bit frightening somehow. I could go down the plughole tomorrow and there's not a single person here who would turn a hair.

It's going to be a long time before I see my friends again, or drink a pint, or go to the National, or play cricket. Didsbury Cricket Club will be in a terrible state next weekend without me. Anyway, I suppose I'll get used to it. They say one gets used to anything in time. What the sages do not say is how much time.

Ten Days Later

Several days have gone quickly by. Each one begins at six o'clock with an assembly on the fort battlements. We stand in the cold in our thin denims and respond with a yell of "ici" when our names are called, and then we are dispatched in small groups on corvée. I have been working at a sawmill for the last few days, during which it hasn't stopped raining--freezing hands fumbling with logs, soaking wet denims, blue with cold. Come on Africa!

11 March 1960

There are a lot of Germans here, with Spaniards and Italians not far behind in numbers. The Italians spend much of their time buying and selling odds and ends or exchanging foreign currencies; God knows why, there's little enough money around. They are born brokers but light on credibility. I have struck up a talking relationship with an English-speaking Dutchman called Hank. He's in bad shape, having run off and left his wife after a family row and he's now regretting it. He has asked to be released, but it is doubtful if they will let him go because it would open the floodgates to all the others who must have changed their minds by now.

There is also an Australian swagman here, and it is good to have somebody who speaks more or less the same language. His name is Treers and three years in the merchant navy as a deckhand and several doses of clap are his chief claim to fame and the core of his conversation.

A Canadian called Gagnon arrived a couple of days after Treers, and he also claims to have had a long and distinguished career in the Canadian navy, but as an officer! Treers doesn't believe it--I can see why--and they are on a collision course. Gagnon is oily and unpleasant material. He brought with him two suitcases full of kit and ingratiated himself by distributing it among the parasites. The brokers could hardly believe their eyes.

Descriere

At 19 years old in 1960, Simon Murray traveled from England to Paris, then to Algeria to begin a five-year stint in the French Foreign Legion. A compelling firsthand account, this gripping chronicle details Murray's experience with the legendary band of soldiers.

Notă biografică

Simon Murray began his working life at eighteen in the British Merchant Navy when he signed on a tramp steamer bound for South America in 1958. He worked in the ship's galley peeling potatoes and swabbing the deck of the gallery floor. Eight months later, he returned to England and became an engineering apprentice in a factory in Northern England. Close to death from boredom, he ran away to join the French Foreign Legion in Algeria, preferring to risk death in the sunshine rather than in the grime of Manchester. Now a highly successful businessman, Murray has directed some of the largest international companies, including Sheraton and Hilton hotels and the Deutsche Bank Group.