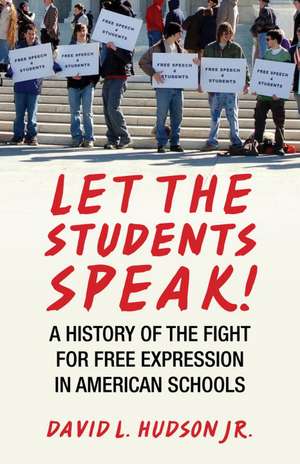

Let the Students Speak!: A History of the Fight for Free Expression in American Schools

Autor Jr. Hudson, David L.en Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 iul 2011

Let the Students Speak! details the rich history and growth of the First Amendment in public schools, from the early nineteenth-century's failed student free-expression claims to the development of protection for students by the U.S. Supreme Court. David Hudson brings this history vividly alive by drawing from interviews with key student litigants in famous cases, including John Tinker of Tinker v. Des Moines Independent School District and Joe Frederick of the "Bong Hits 4 Jesus" case, Morse v. Frederick. He goes on to discuss the raging free-speech controversies in public schools today, including dress codes and uniforms, cyberbullying, and the regulation of any violent-themed expression in a post-Columbine and Virginia Tech environment. This book should be required reading for students, teachers, and school administrators alike.

Preț: 141.79 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 213

Preț estimativ în valută:

27.14€ • 28.19$ • 22.54£

27.14€ • 28.19$ • 22.54£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 03-17 februarie 25

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780807044544

ISBN-10: 0807044547

Pagini: 195

Dimensiuni: 141 x 216 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.28 kg

Editura: Beacon Press (MA)

ISBN-10: 0807044547

Pagini: 195

Dimensiuni: 141 x 216 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.28 kg

Editura: Beacon Press (MA)

Notă biografică

David L. Hudson, Jr. is a First Amendment Scholar with the First Amendment Center at Vanderbilt University. He teaches at Vanderbilt Law School and Nashville School of Law. His articles have been published in the National Law Journal, ABA Journal, and Tennessee Bar Journal. He is a member of the First Amendment Lawyers Association and a graduate of Duke and Vanderbilt Law School.

Extras

Chapter 6

Bong Hits

After the 1988 Hazelwood decision, the U.S. Supreme Court did not take another pure student free expression case for nearly twenty years. This meant that a trio of First Amendment student speech cases governed American jurisprudence for almost two decades—Tinker, Fraser, and Hazelwood. Hazelwood applied to school-sponsored student speech. Thus, a student play, many student newspapers (that weren’t considered public forums), the school’s mascot, or the content of the school’s curriculum could be regulated by school officials if they had a legitimate educational, or pedagogical, reason.

Fraser applied to student speech that was considered vulgar, lewd, or plainly offensive. There was disagreement among the lower courts on at least two aspects of Fraser. First, lawyers, school officials, and eventually judges disagreed as to whether Fraser applied to speech outside the school context or whether it applied only to vulgar and lewd student speech that occurred on school grounds—like Matthew Fraser’s speech to the school assembly. The other question was over the reach of the “plainly offensive prong” of Fraser.

Some schools applied Fraser to any speech they didn’t like. In 1997, Nicholas Boroff, a student at Van Wert High School in Ohio, wore a T-shirt picturing the “shock rocker” Marilyn Manson to school. The T-shirt featured a picture of a three-headed Jesus with the words see no truth, hear no truth, speak no truth. The back of the shirt featured the word believe with the letters lie highlighted in red. School officials deemed Boroff’s shirt to be offensive and to promote values counterproductive to the educational environment; they suspended him. Boroff sued in federal court, asserting his First Amendment rights.

Boroff’s attorney, Chris Starkey, contended that school officials could not punish his client for this T-shirt unless they could show that the shirt was somehow disruptive of school activities. He also argued that the shirt was no more offensive than other T-shirts that school officials allowed. Other students had worn “Slayer” and “MegaDeth” T-shirts without incident. The reason for the censorship, according to Boroff, was what the principal had said to him: the shirt offended people on religious grounds by mocking Jesus.

Both a federal district court and a federal appeals court rejected Boroff’s lawsuit and ruled in favor of school officials. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit in Boroff v. Van Wert Board of Education (2000) determined that school officials could prohibit the T-shirt under the Fraser precedent because the T-shirt was plainly offensive and promoted disruptive and “demoralizing values.”

Other courts also applied a broad reading of Fraser and determined that public schools could ban the Confederate flag because it was a “plainly offensive” symbol. Whatever one thinks of Marilyn Manson or the Confederate flag, if school officials can prohibit any student expression they classify as offensive or conveying offensive ideas, then much student speech is at risk.

Tinker applied to most other student speech that was not school sponsored (Hazelwood) or vulgar or lewd (Fraser). There were differences and questions about Tinker too. In time, more school board attorneys interpreted Tinker narrowly as a case about viewpoint discrimination, in which school officials violated the First Amendment because they singled out a particular armband associated with a particular viewpoint. That is one reading of Tinker, but not the only reading. Others read Tinker more broadly as protecting a wide swath of student speech.

Even though there may have been questions of application about all three decisions, the legal landscape in student speech cases remained relatively stable—at least at the Supreme Court level— for many years. That changed dramatically with “Bong Hits 4 Jesus” and an interesting young man from Juneau, Alaska, named Joseph Frederick.

An Unusual Banner

In January 2002, an eighteen-year-old high school senior named Joseph Frederick conducted his ultimate “free speech experiment.” When he awoke that day, Frederick knew the Olympic Torch Relay for the upcoming Winter Games was scheduled to pass right across from his high school.

Frederick later said that heavy snowfall that day prevented him from pulling his car out of the driveway and making it to school. Whatever the truth of that statement, Frederick had resolved to proceed with an experiment he had been planning. He had become interested in First Amendment issues during that school year, particularly after he decided to refuse to stand and salute the American flag or to recite the Pledge of Allegiance because he had learned about West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette (1943). For his act of recalcitrance, a teacher sent Frederick to the assistant principal’s office.

Frederick knew that he had a First Amendment right to refuse to stand and recite the Pledge of Allegiance. Justice Robert H. Jackson proclaimed such a right in the famous 1943 flag-salute decision when he wrote: “If there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation, it is that no official high or petty shall prescribe what shall be orthodox in matters of politics, religion or other matters of public opinion.”

That didn’t stop school officials from lecturing Frederick about the values of patriotism and love of country. Frederick countered that he loved his country, particularly the Bill of Rights. He believed students should possess First Amendment rights. And he wanted to push the limits.

“I did test the authority of the school administration on numerous occasions,” Frederick said in 2009. “I think it’s mostly my nature; however I was encouraged even more from things I learned in my elective course American Law. In this course most of the semester was spent on a project where each student was assigned a landmark case and had to research it and present it to the class. Then, we would discuss the meaning of the ruling, and our teacher, Gary Lehnhart, would play devil’s advocate in classroom debates with us. I liked asking hypothetical questions a lot.”

Frederick was determined to test a hypothetical he had developed concerning students’ freedom of speech. So, on that snowy January day in 2002, he waited as the Olympic Torch Relay passed near where he was standing on Glacier Avenue, a public street across from his high school, a spot he had mapped out in advance. Television cameras were there to broadcast the relay, the precursor to one of the most high profile of sporting events.

Frederick, with help from fellow students, unveiled his “free speech experiment”—a fourteen-foot banner featuring a most unusual message spelled out in duct tape for the world to see: bong hits 4 jesus. Frederick said that he had seen the message on a snowboard sticker; a band from New Orleans had that stage name as well. “It was my idea alone to ‘do something’ during the torch relay,” Frederick recalled. “It’s hard to say exactly how we made our decision of what to do exactly. My girlfriend and I decided to make a sign of some sort and there were quite a few suggestions from different friends before I finally decided on ‘Bong Hits 4 Jesus.’ ” Whatever the origins of the phrase, Juneau-Douglas High School principal Deborah Morse was less than pleased. She marched across the street and ordered the students to drop the banner. Most quickly complied but Frederick refused. Morse grabbed the banner from Frederick, confiscated it, and ordered him to come to her office. His protestations that his actions were protected by the Bill of Rights and the Constitution fell on deaf ears.

Later that day, Frederick waited to see the principal outside her office. Within a few short hours it was clear that his experiment had produced an unfavorable result. An assistant principal told Frederick that the Bill of Rights did not apply in school—not a good portent for a student waiting to see the principal. Principal Morse then told Frederick that he had violated school policy and had earned himself a five-day suspension. She believed that “Bong Hits 4 Jesus” encouraged illegal drug use—a rampant problem in the public school system. According to Frederick, he responded by quoting the third president of the United States, Thomas Jefferson—“Speech limited is speech lost.”

According to Frederick, Morse did not appreciate the reference to Jeffersonian principles and increased Frederick’s suspension to ten days. For her part Morse disputed Frederick’s account of the Thomas Jefferson quote and the doubling of the suspension. She did acknowledge that Frederick invoked the First Amendment. Whatever the exact nature of the conversation, the scenario set the stage for a legal battle that culminated five years later in Morse v. Frederick, a U.S. Supreme Court decision better known as “Bong Hits 4 Jesus.”

Bong Hits

After the 1988 Hazelwood decision, the U.S. Supreme Court did not take another pure student free expression case for nearly twenty years. This meant that a trio of First Amendment student speech cases governed American jurisprudence for almost two decades—Tinker, Fraser, and Hazelwood. Hazelwood applied to school-sponsored student speech. Thus, a student play, many student newspapers (that weren’t considered public forums), the school’s mascot, or the content of the school’s curriculum could be regulated by school officials if they had a legitimate educational, or pedagogical, reason.

Fraser applied to student speech that was considered vulgar, lewd, or plainly offensive. There was disagreement among the lower courts on at least two aspects of Fraser. First, lawyers, school officials, and eventually judges disagreed as to whether Fraser applied to speech outside the school context or whether it applied only to vulgar and lewd student speech that occurred on school grounds—like Matthew Fraser’s speech to the school assembly. The other question was over the reach of the “plainly offensive prong” of Fraser.

Some schools applied Fraser to any speech they didn’t like. In 1997, Nicholas Boroff, a student at Van Wert High School in Ohio, wore a T-shirt picturing the “shock rocker” Marilyn Manson to school. The T-shirt featured a picture of a three-headed Jesus with the words see no truth, hear no truth, speak no truth. The back of the shirt featured the word believe with the letters lie highlighted in red. School officials deemed Boroff’s shirt to be offensive and to promote values counterproductive to the educational environment; they suspended him. Boroff sued in federal court, asserting his First Amendment rights.

Boroff’s attorney, Chris Starkey, contended that school officials could not punish his client for this T-shirt unless they could show that the shirt was somehow disruptive of school activities. He also argued that the shirt was no more offensive than other T-shirts that school officials allowed. Other students had worn “Slayer” and “MegaDeth” T-shirts without incident. The reason for the censorship, according to Boroff, was what the principal had said to him: the shirt offended people on religious grounds by mocking Jesus.

Both a federal district court and a federal appeals court rejected Boroff’s lawsuit and ruled in favor of school officials. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit in Boroff v. Van Wert Board of Education (2000) determined that school officials could prohibit the T-shirt under the Fraser precedent because the T-shirt was plainly offensive and promoted disruptive and “demoralizing values.”

Other courts also applied a broad reading of Fraser and determined that public schools could ban the Confederate flag because it was a “plainly offensive” symbol. Whatever one thinks of Marilyn Manson or the Confederate flag, if school officials can prohibit any student expression they classify as offensive or conveying offensive ideas, then much student speech is at risk.

Tinker applied to most other student speech that was not school sponsored (Hazelwood) or vulgar or lewd (Fraser). There were differences and questions about Tinker too. In time, more school board attorneys interpreted Tinker narrowly as a case about viewpoint discrimination, in which school officials violated the First Amendment because they singled out a particular armband associated with a particular viewpoint. That is one reading of Tinker, but not the only reading. Others read Tinker more broadly as protecting a wide swath of student speech.

Even though there may have been questions of application about all three decisions, the legal landscape in student speech cases remained relatively stable—at least at the Supreme Court level— for many years. That changed dramatically with “Bong Hits 4 Jesus” and an interesting young man from Juneau, Alaska, named Joseph Frederick.

An Unusual Banner

In January 2002, an eighteen-year-old high school senior named Joseph Frederick conducted his ultimate “free speech experiment.” When he awoke that day, Frederick knew the Olympic Torch Relay for the upcoming Winter Games was scheduled to pass right across from his high school.

Frederick later said that heavy snowfall that day prevented him from pulling his car out of the driveway and making it to school. Whatever the truth of that statement, Frederick had resolved to proceed with an experiment he had been planning. He had become interested in First Amendment issues during that school year, particularly after he decided to refuse to stand and salute the American flag or to recite the Pledge of Allegiance because he had learned about West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette (1943). For his act of recalcitrance, a teacher sent Frederick to the assistant principal’s office.

Frederick knew that he had a First Amendment right to refuse to stand and recite the Pledge of Allegiance. Justice Robert H. Jackson proclaimed such a right in the famous 1943 flag-salute decision when he wrote: “If there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation, it is that no official high or petty shall prescribe what shall be orthodox in matters of politics, religion or other matters of public opinion.”

That didn’t stop school officials from lecturing Frederick about the values of patriotism and love of country. Frederick countered that he loved his country, particularly the Bill of Rights. He believed students should possess First Amendment rights. And he wanted to push the limits.

“I did test the authority of the school administration on numerous occasions,” Frederick said in 2009. “I think it’s mostly my nature; however I was encouraged even more from things I learned in my elective course American Law. In this course most of the semester was spent on a project where each student was assigned a landmark case and had to research it and present it to the class. Then, we would discuss the meaning of the ruling, and our teacher, Gary Lehnhart, would play devil’s advocate in classroom debates with us. I liked asking hypothetical questions a lot.”

Frederick was determined to test a hypothetical he had developed concerning students’ freedom of speech. So, on that snowy January day in 2002, he waited as the Olympic Torch Relay passed near where he was standing on Glacier Avenue, a public street across from his high school, a spot he had mapped out in advance. Television cameras were there to broadcast the relay, the precursor to one of the most high profile of sporting events.

Frederick, with help from fellow students, unveiled his “free speech experiment”—a fourteen-foot banner featuring a most unusual message spelled out in duct tape for the world to see: bong hits 4 jesus. Frederick said that he had seen the message on a snowboard sticker; a band from New Orleans had that stage name as well. “It was my idea alone to ‘do something’ during the torch relay,” Frederick recalled. “It’s hard to say exactly how we made our decision of what to do exactly. My girlfriend and I decided to make a sign of some sort and there were quite a few suggestions from different friends before I finally decided on ‘Bong Hits 4 Jesus.’ ” Whatever the origins of the phrase, Juneau-Douglas High School principal Deborah Morse was less than pleased. She marched across the street and ordered the students to drop the banner. Most quickly complied but Frederick refused. Morse grabbed the banner from Frederick, confiscated it, and ordered him to come to her office. His protestations that his actions were protected by the Bill of Rights and the Constitution fell on deaf ears.

Later that day, Frederick waited to see the principal outside her office. Within a few short hours it was clear that his experiment had produced an unfavorable result. An assistant principal told Frederick that the Bill of Rights did not apply in school—not a good portent for a student waiting to see the principal. Principal Morse then told Frederick that he had violated school policy and had earned himself a five-day suspension. She believed that “Bong Hits 4 Jesus” encouraged illegal drug use—a rampant problem in the public school system. According to Frederick, he responded by quoting the third president of the United States, Thomas Jefferson—“Speech limited is speech lost.”

According to Frederick, Morse did not appreciate the reference to Jeffersonian principles and increased Frederick’s suspension to ten days. For her part Morse disputed Frederick’s account of the Thomas Jefferson quote and the doubling of the suspension. She did acknowledge that Frederick invoked the First Amendment. Whatever the exact nature of the conversation, the scenario set the stage for a legal battle that culminated five years later in Morse v. Frederick, a U.S. Supreme Court decision better known as “Bong Hits 4 Jesus.”

Recenzii

“The lack of respect for student rights by overzealous school administrators is clearly evident in Let the Students Speak. This book is a must-read for free speech enthusiasts, especially when it comes to our future generations.”—Independent Register

“This is an extraordinarily valuable book on the history of free speech in US schools.”—CHOICE

“An interesting and accessible read for upper high school and beyond, the book will appeal to educators, high school students, and parents.”—Library Journal

“Skillfully traces the threads of court opinion and student challenges that have shaped our understanding of students’ freedom to express themselves. Young readers with an interest in law will find Hudson’s book quite readable…"—VOYA (Voice of Youth Advocates)

"David Hudson's Let the Students Speak reflects a masterful blending of law and public policy as it focuses on key issues of free speech in the secondary school context. It should prove as useful and timely for First Amendment lawyers as for school administrators and the broader community, and of course for students and the groups in which they engage. Building on an impressive understanding of where the law has taken us in this field, Hudson wisely warns of the regrettable impact of government censorship upon far too many outspoken students and the messages they seek to convey."-Robert M. O'Neil, Director of the Thomas Jefferson Center for the Protection of Free Expression

“We too often forget that students are also citizens, with the full protection of the Bill of Rights. David Hudson’s authoritative history chronicles the key battles to protect students’ rights, detailing pivotal decisions and controversies in a succinct and compelling manner.”—Ken Paulson, President and CEO, First Amendment Center

“In Let the Students Speak!, David Hudson brings to life the riveting stories of Pearl Pugsley, Lillian and William Gobitis, Mary Beth and John Tinker and many other young people who challenged schools' efforts to punish their speech. Because it explains - in very accessible terms - the human and legal implications of these cases, this important and timely work is an extremely valuable read for anyone interested in the First Amendment, or in education matters generally.”—Helen Norton, Associate Professor, University of Colorado School of Law

“I have profitably read many of David Hudson’s books, and this is among the best. The book is an erudite but engaging study of key cases that involve student speech and speech-related conduct that will prove especially fascinating to high school and college students. The book would make a wonderful supplement to classes studying the First Amendment and an excellent resource for teachers and school administrators seeking to grasp the nuances of student speech.”—Dr. John R. Vile, Professor of Political Science and Dean, University Honors College at Middle Tennessee University, author of Essential Supreme Court Decisions

“Through his work as a scholar with the First Amendment Center, David L. Hudson, Jr. has intimately familiarized himself not only with leading U.S. Supreme Court cases, many of whose participants he has personally interviewed, relative to student speech, but also with some of their obscure state and lower federal court precedents, all of which he skillfully weaves into his narrative. Although clearly aware of the importance of student speech, Hudson also highlights the dangers of “true threats” and “substantial disruption” that such speech can sometimes pose. There is no better book on student speech.”—Dr. John R. Vile, Professor of Political Science and Dean, University Honors College at Middle Tennessee University, author of Essential Supreme Court Decisions

“This is an extraordinarily valuable book on the history of free speech in US schools.”—CHOICE

“An interesting and accessible read for upper high school and beyond, the book will appeal to educators, high school students, and parents.”—Library Journal

“Skillfully traces the threads of court opinion and student challenges that have shaped our understanding of students’ freedom to express themselves. Young readers with an interest in law will find Hudson’s book quite readable…"—VOYA (Voice of Youth Advocates)

"David Hudson's Let the Students Speak reflects a masterful blending of law and public policy as it focuses on key issues of free speech in the secondary school context. It should prove as useful and timely for First Amendment lawyers as for school administrators and the broader community, and of course for students and the groups in which they engage. Building on an impressive understanding of where the law has taken us in this field, Hudson wisely warns of the regrettable impact of government censorship upon far too many outspoken students and the messages they seek to convey."-Robert M. O'Neil, Director of the Thomas Jefferson Center for the Protection of Free Expression

“We too often forget that students are also citizens, with the full protection of the Bill of Rights. David Hudson’s authoritative history chronicles the key battles to protect students’ rights, detailing pivotal decisions and controversies in a succinct and compelling manner.”—Ken Paulson, President and CEO, First Amendment Center

“In Let the Students Speak!, David Hudson brings to life the riveting stories of Pearl Pugsley, Lillian and William Gobitis, Mary Beth and John Tinker and many other young people who challenged schools' efforts to punish their speech. Because it explains - in very accessible terms - the human and legal implications of these cases, this important and timely work is an extremely valuable read for anyone interested in the First Amendment, or in education matters generally.”—Helen Norton, Associate Professor, University of Colorado School of Law

“I have profitably read many of David Hudson’s books, and this is among the best. The book is an erudite but engaging study of key cases that involve student speech and speech-related conduct that will prove especially fascinating to high school and college students. The book would make a wonderful supplement to classes studying the First Amendment and an excellent resource for teachers and school administrators seeking to grasp the nuances of student speech.”—Dr. John R. Vile, Professor of Political Science and Dean, University Honors College at Middle Tennessee University, author of Essential Supreme Court Decisions

“Through his work as a scholar with the First Amendment Center, David L. Hudson, Jr. has intimately familiarized himself not only with leading U.S. Supreme Court cases, many of whose participants he has personally interviewed, relative to student speech, but also with some of their obscure state and lower federal court precedents, all of which he skillfully weaves into his narrative. Although clearly aware of the importance of student speech, Hudson also highlights the dangers of “true threats” and “substantial disruption” that such speech can sometimes pose. There is no better book on student speech.”—Dr. John R. Vile, Professor of Political Science and Dean, University Honors College at Middle Tennessee University, author of Essential Supreme Court Decisions

Cuprins

Editor’s Note (Christopher Finan)

Introduction

1 No Rights for Students

2 The “Fixed Star”

3 Buttons and Armbands

4 A New Era

5 Supreme Retractions

6 Bong Hits

7 Columbine

8 The Dress Debate

9 The New Frontier

Conclusion The Fragile Future

Acknowledgments

Notes

Index of Cases

Introduction

1 No Rights for Students

2 The “Fixed Star”

3 Buttons and Armbands

4 A New Era

5 Supreme Retractions

6 Bong Hits

7 Columbine

8 The Dress Debate

9 The New Frontier

Conclusion The Fragile Future

Acknowledgments

Notes

Index of Cases