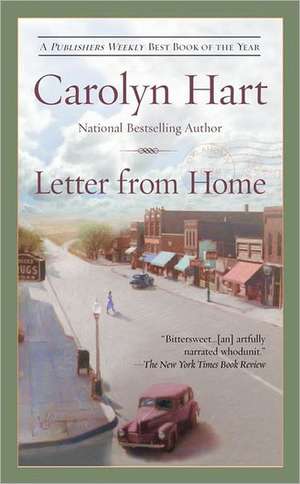

Letter from Home

Autor Carolyn Harten Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 sep 2004 – vârsta de la 18 ani

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

Oklahoma Book Award (2004)

World-renowned journalist G.G. Gilman does her best not to think of the past. But one day she gets a letter—sent from the small Oklahoma town where she grew up—that brings it all back. Memories of people she had once known and loved dearly—and of the sultry summer when her life changed forever.

Preț: 46.43 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 70

Preț estimativ în valută:

8.88€ • 9.30$ • 7.39£

8.88€ • 9.30$ • 7.39£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 10-24 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780425198827

ISBN-10: 0425198820

Pagini: 262

Dimensiuni: 106 x 176 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.13 kg

Editura: Berkley Prime Crime

ISBN-10: 0425198820

Pagini: 262

Dimensiuni: 106 x 176 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.13 kg

Editura: Berkley Prime Crime

Notă biografică

An accomplished master of mystery, Carolyn Hart is the New York Times bestselling author of more than fifty-five novels of mystery and suspense including the Bailey Ruth Ghost Novels and the Death on Demand Mysteries. Her books have won multiple Agatha, Anthony, and Macavity awards. She has also been honored with the Amelia Award for significant contributions to the traditional mystery from Malice Domestic and was named a Grand Master by the Mystery Writers of America. One of the founders of Sisters in Crime, Hart lives in Oklahoma City, where she enjoys mysteries, walking in the park, and cats. She and her husband, Phil, serve as staff--cat owners will understand--to brother and sister brown tabbies.

Extras

Chapter One THE RUSTED IRON gate sagged from the stone pillar. A winter-brown vine clung to the stones. Pale March sunlight filtered through the bare branches of sycamores and oaks, throwing thin black shadows as distinct as stylized brushwork in a Japanese painting. My cane poked through a mound of tawny leaves, some wizened and wrinkled as old faces, some damp and soggy, smelling of must and rot and decay. The rutted road looked much narrower than I remembered. When I'd last been in the cemetery, most of the headstones, even those dating back to Indian Territory days, had stood straight. Now many were tilted and some had tumbled to the ground, half hidden by leaves. Remnants of a late snow spangled shaded spots.

I walked slowly, stabbing my cane at the uneven ground. Nothing looked familiar. Our graves were surely this way.... Oh, of course. The weeping willow was gone. I'd always marked our family plot by a huge willow, its dangling fronds shiny green in summer, bare and brown in winter. A stump leaned crookedly near the plot.

I paused to rest for a moment. The sharp wind rustled the bare branches of the sycamores and oaks. I shivered, grateful for the warmth of my cashmere coat and leather gloves. I plunged my left hand into a pocket of my coat. My gloved fingers closed around the letter. The name on the return address had not been familiar, but I had recognized the postmark. My first thought when I received the square cream envelope had been as instinctive as breathing: Why, it's a letter from home. Second came a quiver of utter surprise. Home? I'd not been back to the little town in northeastern Oklahoma since I was a girl. Home ...

When I opened the envelope and lifted out three pages-cheap paper with violently colored roses twining down one side, the writing a dense, almost indecipherable scrawl-I almost threw the sheets away unread. The salutation stopped me: Dear Gretchen. No one had called me Gretchen for well over a half century. Gretchen ... Across a span of time, I remembered a girl, dark-haired, blue-eyed, slim and eager, who seemed quite separate and distinct from the old woman walking determinedly toward the graves.

I remembered that long-ago girl....

GRETCHEN CLUTCHED THE folded sheaf of yellow copy paper and a thick dark-leaded pencil, sharp enough for writing but the point too blunt to break. That was just how Mr. Dennis did it when he covered the city council. Her first day at the Gazette, he'd waggled a thick handful of copy paper. "This is all you need, Gretchen. Take some paper and a couple of pencils, listen hard, make notes you can read, write your story fast."

It still seemed strange to walk toward Victory Café and not hurry inside, welcoming the familiar smells of cinnamon rolls and coffee and bacon. Victory Café-she was almost used to the name now. It used to be Pfizer Café but after Pearl Harbor when people began to talk about Nazis and Krauts as well as the Japs, Grandmother hired Elwyn Haskins to paint a new name in bright red and blue against a white background: Victory Café There was a small American flag near the cash register and the mirror behind the counter held pictures of men in the service. Anyone could bring a photo and Grandmother would tape it up. Now people were beginning to believe in victory, especially since the invasion, though it seemed that the convoys rolling through on Highway 66 were longer than ever and the trains clacking past day and night pulled more and more flatcars carrying tanks and trucks and jeeps. Sometimes soldiers leaned from open windows and waved.

Gretchen stopped for the red light at Broadway and Main. She waited impatiently. The light was new and lots of people honked their horns at it when they had to stop. There'd been a big fight in city council about putting in a stoplight. Mayor Burkett got his way, insisting their town needed the light. After all, he'd pointed out, everything was different because of the war and they had plenty of traffic, people stopping off from Highway 66 and soldiers coming over the Missouri line from Camp Crowder and local folks streaming into town to buy whatever shopkeepers had to offer. There were lots of people in town every day, but most of them were old or middle-aged. The young men in uniform were never there for long, off for three-day passes and sometimes ten-day furloughs before their units were set to ship out. There wasn't much to buy, but people had money from war work. Lots of townspeople like Gretchen's mom had gone to Tulsa to work in the Douglas plant. Mom was making good money, more than they'd ever seen, thirty-five dollars a week. The Billup Shoe Store had closed. Mr. Billup couldn't get enough shoes. Most everybody had to depend upon friends or family to find shoes at Froug's or Brown-Dunkin in Tulsa and rationing only allowed two pairs a year anyway. Mr. Pinkley's gas station went out of business, but there was a motel-Sweet Dreams-on the edge of town, and some new little houses built from lumber salvaged from old barns and the abandoned Morris home. Mr. McCrory's gas station was going great guns despite rationing. He specialized in repairs and everybody needed to keep their old cars running for the duration.

When the light changed, Gretchen hurried across the street. She wanted to run, but she held herself to a fast walk. She, Gretchen Grace Gilman, was on her way to the courthouse, the big red sandstone building that looked like a castle with bays and turrets. When she was little, she'd made up a story in her mind about a princess held captive in a turret and a handsome swashbuckler like Errol Flynn leaping ledge to ledge, sword in hand, coming to the rescue of the fair maiden. That had been exciting but nothing to compare to the excitement she felt now. The courthouse was her beat and so was city hall on Cimarron Street. Of course, Mr. Dennis or Mr. Cooley covered the big stories, but there was plenty for Gretchen to write about. She'd been to both the courthouse and city hall first thing this morning, checked the sheriff's office for any overnight calls, asked the court clerk about lawsuits, dropped by the county records office to see about deeds registered, and scanned the police blotter at the police station. This was her last run to the courthouse and city hall for the day. She'd already turned in her stories for today's paper. Last deadline was one o'clock, but that was for late-breaking news, wire stories from the war front, especially the fighting in Normandy. Ever since D-Day, they'd had a map on page 1 showing the progress of the fighting. Most of her stories were turned in by ten. The press run was at two. She glanced across Main at the café. The windows needed a wash. Mrs. Perkins did a pretty good job. But she couldn't-or wouldn't-move as fast as Gretchen and she didn't help Grandmother the way Gretchen did when she worked there. That's how Gretchen had expected to spend the summer until the miracle happened: Mrs. Jacobs, the junior high English teacher, telling Mr. Dennis that Gretchen wanted to grow up and be a reporter and that she'd make a good hand while the Gazette was so short-staffed because of the war. Mrs. Jacobs told Gretchen to go ask for a job when Joe Bob Terrell was drafted. Gretchen had put on her favorite dress-a yellow-and-white-checked dirndl with starfish appliqués at the shoulder and near the hem and white ricrac as an accent at the neck, waist, and skirt-and pulled on short white gloves and a yellow straw hat. She didn't have any good summer shoes, but she'd taken her white sandals and polished them and hoped Mr. Dennis wouldn't notice that the straps were frayed. She'd never forget, never in a thousand million years, that May afternoon. School was almost out and Mrs. Jacobs got her excused from last hour. It was only May but it was hot, the temperature nudging toward ninety. Everybody said it was going to be a hot summer, the summer of 1944. But Gretchen didn't remember any summers when it hadn't been hot and dry and sometimes the wind blew dust through town, coating the buildings, turning the sky a smudgy orange. At the café, they'd wipe everything with a damp cloth, but it was hard to keep the dust out of the booths and off the tables and chairs and they'd come home to a house with a fine layer of dust on everything. It wasn't dusty that May afternoon. The sky glittered a sharp, bright, clear blue and she'd held tight to her hat as the Oklahoma wind gusted, bending the trees, skittering trash down the street. When she got to the Gazette office, she'd stared at the door and been so scared she'd almost turned and run away. Could she do it? She was editor of the Wolf Cry, the junior high newspaper. Mrs. Jacobs liked her stories, had given her bylines all this past year. One story, the one about Millard, Mrs. Jacobs sent in to the interscholastic contest. When Gretchen won first prize, she'd felt funny, happy, and sad at the same time. But Millard would have been proud for her. Mrs. Jacobs had told Gretchen to cut out all her stories and take them to show Mr. Dennis. Mrs. Jacobs called them "clips." Somehow, her hand sweaty, her stomach a hard tight knot, Gretchen opened the door and walked inside. To her left was a door marked ADVERTISING CIRCULATION. Straight ahead was a square room with a half dozen desks. A telephone shrilled. In one corner, the clacking Teletype spewed out paper in an endless stream. Mrs. Jacobs had brought their whole class to visit the Gazette last fall and she'd been most excited to show them the Teletype, the very latest news from United Press coming in over a leased wire. Only one desk was occupied. A stocky man, shiny bald except for a fringe of gray hair, typed so fast it sounded like a machine gun. Smoke wreathed upward from a pipe cradled in a ceramic ashtray shaped like the state of Oklahoma. A door in the far wall banged open. A smell of hot metal rolled toward her. An old man with long sideburns and a big white mustache stuck out his head, shouting to be heard over a clattery metallic noise. "That newsprint ain't here yet, Walt. You better check again." The door slammed, cutting off the metal ping of the Linotypes, making the newsroom seem quiet in comparison. Gretchen walked slowly toward the occupied desk. "Mr. Dennis."

He continued to hunch over the big old typewriter, eyes squinting in concentration, fingers flying.

"Mr. Dennis." His head jerked around. Deep lines grooved the editor's round face. His mouth turned down. Greenish blue eyes glittered beneath bristly brows. He glowered. "What do you want, girl?"

Gretchen wanted to run away. But he'd told Mrs. Jacobs he had to have somebody quick. Gretchen thrust out her hand with the folder holding her clips. Her hand shook. "Mrs. Jacobs said for me to bring my clips. I'm Gretchen Gilman."

He grabbed his pipe, took a deep puff. His thick eyebrows were tufted like an owl's. He snapped, "I told her I wanted a boy. She said nobody was good enough. So here you are." The emphasis on the pronoun was sour. "How old are you, girl?"

Gretchen stood as tall as her five feet three inches would stretch. "I'm almost fourteen." Well, she'd be fourteen in September. That was almost, wasn't it?

"Fourteen." He heaved a sigh. "God damn this war." He puffed on the pipe, pinned her with his glittering eyes. "Can you write, girl?"

"Yes." Her answer came out clear and definite, as definite as the crack of the exhaust when Dr. Jamison floorboarded his old car, as definite as the peal of the bells from the Catholic church on Sunday mornings, as definite as the big, black headlines yesterday about the Germans fleeing Monte Cassino.

The editor studied her a moment longer, reached out for her clips, riffled through them, stopped to read one. He took so long, Gretchen knew he was reading it twice. When he looked up, his dark impatient glance swept her up and down. "Don't believe in women in a newsroom. Except for soc." He pronounced it "sock," his voice a rasp, reflecting a newsman's disdain for the fluff of the society page. "But there's a war on." He tapped the sheet. She leaned forward and knew it was the story about Millard. "I guess you know that. Okay, girl. We'll give it a try." He handed back the clips. "You can start now. Take the plain yellow desk at the back. The metal desk belongs to Willie Hurst. Sports. He retired years ago, but he's back to help me out. Willie's off to San Antonio for his grandson's wedding. The desk that looks like a tornado hit it belongs to Ralph Cooley. He used to work for INS."

Gretchen's eyes widened. INS! She'd never known anybody who was a reporter for one of the wire services. Mrs. Jacobs had told her all about the three wire services, International News Service, Associated Press, and United Press. Nobody ever called them by those long names. They were INS, AP, and UP. To be a reporter for one of them was as magical to Gretchen as owning a flying carpet.

Mr. Dennis puffed out his cheeks in exasperation. "Used to." His tone was dry and a little sad. "But I got to use him. There's nobody else left. Joe Bob Terrell got called up. He left last week." The editor jerked his head. "The desk with the rose in a vase is Jewell Taylor's. Soc. Get on the phone, call the police station, ask if there's anything new on the blotter. You can come in every afternoon after school and we'll see how you do. If you work out, you'll be full time when school's out. Five bucks a week."

As Gretchen moved past, her heart thudding, the editor glanced at her hat. "School clothes will do from now on."

And here she was, a reporter for the Gazette, out on her beat. Gretchen took the courthouse steps two at a time. It seemed a long time ago that she'd first walked into the Gazette office. Now it was a familiar place. She still tensed whenever Mr. Dennis called her name, but he didn't glower at her anymore. Yesterday, when she wrote a story on Rose Drew's plans to go to San Diego to see her husband, a navy petty officer, before his ship left port, Gretchen almost hadn't turned it in. She'd laid the story next to her typewriter and poked in another sheet of copy paper and started the kind of story she knew Mr. Dennis expected:

Mrs. Wilford Drew will take the train to California next Tuesday in hopes of bidding her husband farewell before his ship leaves for the Pacific theater. Mrs. Drew has worked at Osgood Beauty Salon for eight years. She ...

Gretchen yanked out the sheet, threw it away. She picked up her first effort, pasted the three pages together, and placed them in the incoming copy tray on Mr. Dennis's desk. She went back to her desk and began typing up the list of civic club meetings, shoulders tensed, waiting for Mr. Dennis to clear his throat, the grumbling roar that usually preceded a spate of impatient instruction.

He cleared his throat. "Girl."

She sat still and tight.

Descriere

In this "Publishers Weekly" Best Book of the Year, set in the summer of 1944, journalist Gretchen Gilman gets a letter from her small Oklahoma hometown, which brings back memories of the people she had once known. But this summer, life there will change forever.

Premii

- Oklahoma Book Award Finalist, 2004