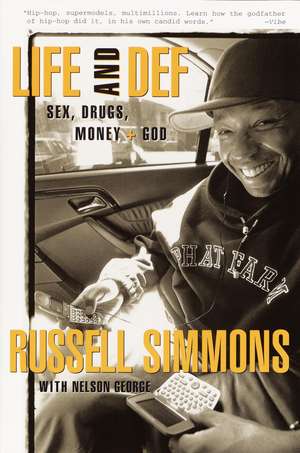

Life and Def: Sex, Drugs, Money, + God

Autor Russell Simmons Nelson Georgeen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 aug 2002

In his own brash, compelling voice, Simmons chronicles his numerous business successes and occasional failures. He tells the story of the founding of the legendary Def Jam Records, whose roster stretches from original rap icons like L.L. Cool J, Public Enemy, and the Beastie Boys to today’s top stars, including Jay-Z and DMX. He traces the launching of Def Comedy Jam, the long-running hit television series that introduced a new generation of black comedic stars to America, from Martin Lawrence and Bill Bellamy to Bernie Mac and Chris Rock. He spins hilarious tales of his adventures in Hollywood, where he’s produced hit movies like Eddie Murphy’s The Nutty Professor and worked with quirky geniuses like Abel Ferrara. He also tells the story of Phat Farm, the wildly successful pioneering urban clothing label whose origins lay in Russell’s longtime fascination with fashion (and fashion models).

Simmons’s story is also one of personal transformation, from the driven man who in the heady days of early success indulged himself with drugs, sex, and world-class decadence to the husband and father he is today, a man who has found meaning in activism, philanthropy, and spiritual practice while never losing his passion for the social, political, artistic, and commercial potential of hip-hop.

Through it all he relates telling anecdotes about the characters he’s dealt with: models and gangsters, street poets and gurus, and major players like Donald Trump, Sean Combs, Jon Peters, and Tupac Shakur. Full of advice, opinions, and behind-the-scenes scoop, Life and Def is the story of the quintessential hip-hop life.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 120.78 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 181

Preț estimativ în valută:

23.11€ • 24.04$ • 19.08£

23.11€ • 24.04$ • 19.08£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 24 martie-07 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780609807156

ISBN-10: 0609807153

Pagini: 288

Ilustrații: TWO 16-PP. B&W INSERTS

Dimensiuni: 155 x 231 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.43 kg

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

ISBN-10: 0609807153

Pagini: 288

Ilustrații: TWO 16-PP. B&W INSERTS

Dimensiuni: 155 x 231 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.43 kg

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

Notă biografică

RUSSELL SIMMONS is the founder or cofounder of numerous successful companies and philanthropic organizations, including Def Jam Records, Phat Farm clothing, the dRush advertising agency, and Rush Philanthropic.

NELSON GEORGE is a groundbreaking journalist, cultural critic, novelist, and filmmaker. Among his nine books are Show and Tell, the award-winning Death of Rhythm & Blues, and Hip Hop America,. He can be reached at www.nelsongeorge.com.

From the Hardcover edition.

NELSON GEORGE is a groundbreaking journalist, cultural critic, novelist, and filmmaker. Among his nine books are Show and Tell, the award-winning Death of Rhythm & Blues, and Hip Hop America,. He can be reached at www.nelsongeorge.com.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

1

Cold Gettin' Paid

There have always been two types of black businesses in this country. First, there are those like Johnson Publications or Essence Communications (or black hair care or cosmetics companies), which cater to black consumers and work that niche for all it's worth. Ebony and Essence, which are institutions in the black community, exist solely to target black consumers, draw revenue predominantly from the ad budgets of white corporations and portray a middle-class black version of American reality.

Then there's the Motown model. Berry Gordy labeled his company the "Sound of Young America." Gordy was a visionary who saw that black culture, as expressed through the music his company created, was just as viable and important culturally--and commercially--as anything in this country. Motown sold black pop music, written and performed by blacks, for consumption by all Americans regardless of their color.

My philosophy takes a little from both, yet differs fundamentally from them. Unlike Ebony or Essence, my audience is not limited by race. My core audience, my hip-hop audience, is black and white, Asian and Hispanic--anyone who totally identifies with and lives in the culture. Those are my peeps.

And unlike Motown, I don't believe in catering to the so-called mainstream by altering your look or slang or music. I see hip-hop culture as the new American mainstream. We don't change for you; you adapt to us. That's what has made Def Jam records, Def Comedy Jam and Phat Farm, to name a few of my ventures, commercially successful and influential. And that is the central philosophy that has driven my career.

WHAT IS HIP-HOP?

I guess I should start with my definition of hip-hop. To me, hip-hop is modern mainstream young urban American culture. I know there's a lot of ideas there, but hip-hop's impact is as broad as that description suggests. Like rock and roll, blues and jazz, hip-hop is primarily a musical form. But unlike those forms of black American music, hip-hop is more expansive in the ways it manifests itself, and as a result, its impact is wider. The ideas of hip-hop are spread not just through music, but in fashion, movies, television, advertising, dancing, slang and attitude.

The beauty of hip-hop, and a key to its longevity, is that within the culture there is a lot of flexibility. So Run-D.M.C. and A Tribe Called Quest and N.W.A and Mary J. Blige and Luther Campbell and the Beastie Boys can all wear different clothes, use different slang and have a different kind of cultural significance. Yet all are recognizable as being part of hip-hop. I believe hip-hop is an attitude, one that can be nonverbal as well as eloquent. It communicates aspiration and frustration, community and aggression, creativity and street reality, style and substance. It is not rigid, nor is it easy to sum up in one sentence or even one book. Simply put, when you are in a hip-hop environment, you know it; it has a feel that is tangible and cannot be mistaken for anything else.

Hip-hop culture is, all these years later, closer to its original aesthetics than jazz or blues or rock and roll are to their roots. For example, the originators of rock and roll were black men who wore fly suits, had their hair slick and didn't give a fuck. That describes all those artists in the '50s who laid down the foundation, men who were trying to fight their way out of southern racism and northern poverty. In their time they were regarded as outlaws. They got arrested. They got harassed. They were attacked.

Eventually mainstream America took over rock and roll and it changed. No longer rock and roll, it became rock. It became hallucinogenic. It became about rebellion for rebellion's sake. It was no longer about drinking and looking fly; it became about taking drugs and wearing dirty jeans. In the '60s and '70s, when this new rock emerged, the old music, and the old musicians, were tossed away. You couldn't tell this new audience that Chuck Berry and Led Zeppelin were the same thing. In one generation you were hot and then you were over.

Hip-hop, however, has been very consistent in its stance. A couple of years ago Erick Sermon, Redman and Keith Murray recorded the Sugarhill Gang's "Rapper's Delight," the first big rap hit from 1979, and did it exactly like the original. The concepts in that rap record from twenty-odd years ago are still valid. Hip-hop records are still about "I got a fly girl, I'm going to the motel in my new car." They still say, "I'm gonna get flak for being young and street. But I'm still gonna take a bite out of American culture. I'm gonna do it my way and I'm gonna buy everything in Bloomingdale's. I'm not into rebellion for the sake of rebelling. My rebellion has a goal-self-improvement, the ability to acquire all the things normally denied me or to change the way the world speaks, moves, dresses and thinks." So "Rapper's Delight," which basically borrowed rhymes from old-school pioneers, has the same aesthetic as you'd find on almost any Def Jam record today. Then it was gold chains. Now it's platinum Bentleys.

Which is why there are 40-year-old b-boys. I remember flying to a fight in Vegas and meeting the actor Ving Rhames and his wife. Turned out his brother was a competitor of mine in the old days who used to promote shows by DJ Hollywood and sell thousands of tickets. Ving and I talked about going to the Hotel Diplomat in Times Square, where we did big parties in the days before rap records. But we were also talking about the sound on a new Q-Tip record and how dope he was.

Ving and a lot of people like him are getting the same thing out of the culture they used to. The music isn't the same. Sometimes the language on the record is different. But it's the same take on American culture.

In the beginning we ran into a little bit of an obstacle when it came to communicating this urban black and Latino attitude to suburban America. Even after suburbanites began buying the music, they didn't really understand the aesthetic. Now, in the twenty-first century, it's come full circle. Suburbanites purchase hip-hop records in huge numbers, but they also have a deeper understanding of and appreciation for all aspects of the culture. As a result, hip-hop has influenced everything around them. Look at today's rock bands-Limp Bizkit, Kid Rock, Korn. They all have hip-hop running through their veins.

You know, rock stars used to be notorious for getting into brawls and getting drunk. In the '60s and '70s, when rock still had some guts, people like Mick Jagger and Jimmy Page represented youthful rebellion. They did drugs. They tore up hotel rooms. They made sexually suggestive records. They expressed sympathy for the devil. Now rap stars have taken it all to another level. They carry guns. They use guns. They go to jail. They express a connection to the people still in jail. They express solidarity with the people from their hood-no matter how dangerous it was or how much money they've made. They confront cops, politicians, other rappers and even themselves on record and off. They do all the things rock stars used to do and they do even more dangerous, outrageous things. Today a kid knows a rock star acts out because he's rebelling against his parents. A rap star, however, is doing it because he has a serious reason-discrimination, personal anger or ghetto conditions. And on top of all that, a rap star wants to make money and enjoy success, and is fearless in doing it. The result is the kind of attitude of authentic rebellion that rock was always supposed to have.

This stance has drawn criticism, but attacks on hip-hop have always been great for the culture. In fact, I personally want to thank Bob Dole, William Bennett and the rest of those right-wingers for reminding kids that hip-hop is theirs. When adults say, "Oh, fuck, don't listen to rap!" they just reinforce young people's commitment to it. Even some 40-year-olds who grew up on rap and who know that the messages in rap can be scary try to tell their kids, "Don't listen to it," which is like asking kids to buy it. People who grew up on rock now look at it and say, "Aw, it's okay," because it's not scary at all. Once that happens, kids don't want it and it becomes a museum piece.

On the other hand, black kids, and the core white, Asian and Latino kids into rap, don't listen to it just to piss off their parents. That kind of rebellion's irrelevant to them. They listen because it expresses what they're thinking about. Punk, new wave, alternative-most of it came and went. Today there's no Clash. There's no Nirvana. Right now rock can't fuck with rap-unless it adopts rap-because the culture is so raw and honest.

When rap came along in the late '70s, there was something synthetic about black pop music. The most popular black music of the time was R&B made simple for white people to dance to; they called it disco. Disco actually started within the gay dance community. They had a creative little thing happening, and then it crossed over to the mainstream. The record industry adopted it because it helped soften the edges of black music. But ultimately disco didn't address the issues rap has. Even though rap was born in the ghetto, it addresses issues a lot of kids across America (and the world) are dealing with-anger, alienation, hypocrisy, sex, drugs. All the basics.

Kids of all colors, all over the world, instinctively seek to change the world. They usually have this desire because they don't want to buy into the dominant values of the mainstream. Rappers want to change the world to suit their vision and to create a place for themselves in it. So kids can find a way into hip-hop by staying true to their instinct toward rebellion and change.

Hip-hop has, in fact, changed the world. It has taken something from the American ghetto and made it global. It has become the creative touchstone for edgy, progressive and aggressive youth culture around the world. That's why my business is bigger than it's ever been. And, I believe, we're far from through.

From the Hardcover edition.

Cold Gettin' Paid

There have always been two types of black businesses in this country. First, there are those like Johnson Publications or Essence Communications (or black hair care or cosmetics companies), which cater to black consumers and work that niche for all it's worth. Ebony and Essence, which are institutions in the black community, exist solely to target black consumers, draw revenue predominantly from the ad budgets of white corporations and portray a middle-class black version of American reality.

Then there's the Motown model. Berry Gordy labeled his company the "Sound of Young America." Gordy was a visionary who saw that black culture, as expressed through the music his company created, was just as viable and important culturally--and commercially--as anything in this country. Motown sold black pop music, written and performed by blacks, for consumption by all Americans regardless of their color.

My philosophy takes a little from both, yet differs fundamentally from them. Unlike Ebony or Essence, my audience is not limited by race. My core audience, my hip-hop audience, is black and white, Asian and Hispanic--anyone who totally identifies with and lives in the culture. Those are my peeps.

And unlike Motown, I don't believe in catering to the so-called mainstream by altering your look or slang or music. I see hip-hop culture as the new American mainstream. We don't change for you; you adapt to us. That's what has made Def Jam records, Def Comedy Jam and Phat Farm, to name a few of my ventures, commercially successful and influential. And that is the central philosophy that has driven my career.

WHAT IS HIP-HOP?

I guess I should start with my definition of hip-hop. To me, hip-hop is modern mainstream young urban American culture. I know there's a lot of ideas there, but hip-hop's impact is as broad as that description suggests. Like rock and roll, blues and jazz, hip-hop is primarily a musical form. But unlike those forms of black American music, hip-hop is more expansive in the ways it manifests itself, and as a result, its impact is wider. The ideas of hip-hop are spread not just through music, but in fashion, movies, television, advertising, dancing, slang and attitude.

The beauty of hip-hop, and a key to its longevity, is that within the culture there is a lot of flexibility. So Run-D.M.C. and A Tribe Called Quest and N.W.A and Mary J. Blige and Luther Campbell and the Beastie Boys can all wear different clothes, use different slang and have a different kind of cultural significance. Yet all are recognizable as being part of hip-hop. I believe hip-hop is an attitude, one that can be nonverbal as well as eloquent. It communicates aspiration and frustration, community and aggression, creativity and street reality, style and substance. It is not rigid, nor is it easy to sum up in one sentence or even one book. Simply put, when you are in a hip-hop environment, you know it; it has a feel that is tangible and cannot be mistaken for anything else.

Hip-hop culture is, all these years later, closer to its original aesthetics than jazz or blues or rock and roll are to their roots. For example, the originators of rock and roll were black men who wore fly suits, had their hair slick and didn't give a fuck. That describes all those artists in the '50s who laid down the foundation, men who were trying to fight their way out of southern racism and northern poverty. In their time they were regarded as outlaws. They got arrested. They got harassed. They were attacked.

Eventually mainstream America took over rock and roll and it changed. No longer rock and roll, it became rock. It became hallucinogenic. It became about rebellion for rebellion's sake. It was no longer about drinking and looking fly; it became about taking drugs and wearing dirty jeans. In the '60s and '70s, when this new rock emerged, the old music, and the old musicians, were tossed away. You couldn't tell this new audience that Chuck Berry and Led Zeppelin were the same thing. In one generation you were hot and then you were over.

Hip-hop, however, has been very consistent in its stance. A couple of years ago Erick Sermon, Redman and Keith Murray recorded the Sugarhill Gang's "Rapper's Delight," the first big rap hit from 1979, and did it exactly like the original. The concepts in that rap record from twenty-odd years ago are still valid. Hip-hop records are still about "I got a fly girl, I'm going to the motel in my new car." They still say, "I'm gonna get flak for being young and street. But I'm still gonna take a bite out of American culture. I'm gonna do it my way and I'm gonna buy everything in Bloomingdale's. I'm not into rebellion for the sake of rebelling. My rebellion has a goal-self-improvement, the ability to acquire all the things normally denied me or to change the way the world speaks, moves, dresses and thinks." So "Rapper's Delight," which basically borrowed rhymes from old-school pioneers, has the same aesthetic as you'd find on almost any Def Jam record today. Then it was gold chains. Now it's platinum Bentleys.

Which is why there are 40-year-old b-boys. I remember flying to a fight in Vegas and meeting the actor Ving Rhames and his wife. Turned out his brother was a competitor of mine in the old days who used to promote shows by DJ Hollywood and sell thousands of tickets. Ving and I talked about going to the Hotel Diplomat in Times Square, where we did big parties in the days before rap records. But we were also talking about the sound on a new Q-Tip record and how dope he was.

Ving and a lot of people like him are getting the same thing out of the culture they used to. The music isn't the same. Sometimes the language on the record is different. But it's the same take on American culture.

In the beginning we ran into a little bit of an obstacle when it came to communicating this urban black and Latino attitude to suburban America. Even after suburbanites began buying the music, they didn't really understand the aesthetic. Now, in the twenty-first century, it's come full circle. Suburbanites purchase hip-hop records in huge numbers, but they also have a deeper understanding of and appreciation for all aspects of the culture. As a result, hip-hop has influenced everything around them. Look at today's rock bands-Limp Bizkit, Kid Rock, Korn. They all have hip-hop running through their veins.

You know, rock stars used to be notorious for getting into brawls and getting drunk. In the '60s and '70s, when rock still had some guts, people like Mick Jagger and Jimmy Page represented youthful rebellion. They did drugs. They tore up hotel rooms. They made sexually suggestive records. They expressed sympathy for the devil. Now rap stars have taken it all to another level. They carry guns. They use guns. They go to jail. They express a connection to the people still in jail. They express solidarity with the people from their hood-no matter how dangerous it was or how much money they've made. They confront cops, politicians, other rappers and even themselves on record and off. They do all the things rock stars used to do and they do even more dangerous, outrageous things. Today a kid knows a rock star acts out because he's rebelling against his parents. A rap star, however, is doing it because he has a serious reason-discrimination, personal anger or ghetto conditions. And on top of all that, a rap star wants to make money and enjoy success, and is fearless in doing it. The result is the kind of attitude of authentic rebellion that rock was always supposed to have.

This stance has drawn criticism, but attacks on hip-hop have always been great for the culture. In fact, I personally want to thank Bob Dole, William Bennett and the rest of those right-wingers for reminding kids that hip-hop is theirs. When adults say, "Oh, fuck, don't listen to rap!" they just reinforce young people's commitment to it. Even some 40-year-olds who grew up on rap and who know that the messages in rap can be scary try to tell their kids, "Don't listen to it," which is like asking kids to buy it. People who grew up on rock now look at it and say, "Aw, it's okay," because it's not scary at all. Once that happens, kids don't want it and it becomes a museum piece.

On the other hand, black kids, and the core white, Asian and Latino kids into rap, don't listen to it just to piss off their parents. That kind of rebellion's irrelevant to them. They listen because it expresses what they're thinking about. Punk, new wave, alternative-most of it came and went. Today there's no Clash. There's no Nirvana. Right now rock can't fuck with rap-unless it adopts rap-because the culture is so raw and honest.

When rap came along in the late '70s, there was something synthetic about black pop music. The most popular black music of the time was R&B made simple for white people to dance to; they called it disco. Disco actually started within the gay dance community. They had a creative little thing happening, and then it crossed over to the mainstream. The record industry adopted it because it helped soften the edges of black music. But ultimately disco didn't address the issues rap has. Even though rap was born in the ghetto, it addresses issues a lot of kids across America (and the world) are dealing with-anger, alienation, hypocrisy, sex, drugs. All the basics.

Kids of all colors, all over the world, instinctively seek to change the world. They usually have this desire because they don't want to buy into the dominant values of the mainstream. Rappers want to change the world to suit their vision and to create a place for themselves in it. So kids can find a way into hip-hop by staying true to their instinct toward rebellion and change.

Hip-hop has, in fact, changed the world. It has taken something from the American ghetto and made it global. It has become the creative touchstone for edgy, progressive and aggressive youth culture around the world. That's why my business is bigger than it's ever been. And, I believe, we're far from through.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Simmons managed what most of us only dream about: igniting a revolution rather than witnessing one.” —Gotham

“An unbelievably fascinating and provocative account that I found hard to put down. Life and Def is Russell’s

Art of the Deal.” —Donald Trump

“Urban legend Russell Simmons nearly single-handedly made rap music and culture mainstream. An African-American Horatio Alger tale.” —New York Post

“An inspiring glimpse at the rap impresario’s road to redemption.” —Essence

“In Life and Def, hip-hop’s mega-mogul gives the raw, uncut story behind his rise to the top.” —Honey

“Simmons’s love for hip-hop in general, and rap in particular, can’t be mistaken. This book is insightful. . . . Anybody who cares about rap should read this.” —Black Issues Book Review

“Groundbreaking . . . a serious blueprint of how to create a multimillion-dollar empire.” —New York Amsterdam News

“An unbelievably fascinating and provocative account that I found hard to put down. Life and Def is Russell’s

Art of the Deal.” —Donald Trump

“Urban legend Russell Simmons nearly single-handedly made rap music and culture mainstream. An African-American Horatio Alger tale.” —New York Post

“An inspiring glimpse at the rap impresario’s road to redemption.” —Essence

“In Life and Def, hip-hop’s mega-mogul gives the raw, uncut story behind his rise to the top.” —Honey

“Simmons’s love for hip-hop in general, and rap in particular, can’t be mistaken. This book is insightful. . . . Anybody who cares about rap should read this.” —Black Issues Book Review

“Groundbreaking . . . a serious blueprint of how to create a multimillion-dollar empire.” —New York Amsterdam News