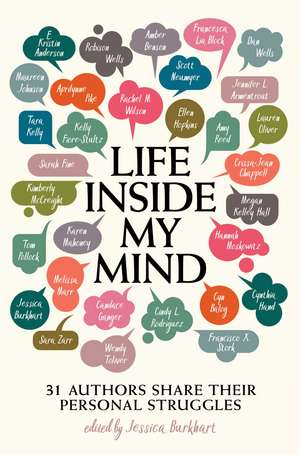

Life Inside My Mind: 31 Authors Share Their Personal Struggles

Editat de Jessica Burkhart Autor Maureen Johnson, Robison Wells, Lauren Oliver, Jennifer L. Armentrout, Amy Reed, Aprilynne Pike, Rachel M. Wilson, Dan Wells, Amber Benson, E. Kristin Anderson, Sarah Fine, Kelly Fiore-Stultz, Ellen Hopkins, Scott Neumyer, Crissa-Jean Chappell, Francesca Lia Block, Tara Kelly, Kimberly McCreight, Megan Kelley Hall, Hannah Moskowitz, Karen Mahoney, Tom Pollock, Cyn Balog, Melissa Marr, Wendy Toliver, Cindy L. Rodriguez, Candace Ganger, Sara Zarr, Cynthia Hand, Francisco X. Storken Limba Engleză Paperback – 17 apr 2019 – vârsta de la 14 ani

“[A] much-needed, enlightening book.” —School Library Journal (starred review)

Your favorite YA authors including Ellen Hopkins, Maureen Johnson, and more recount their own experiences with mental health in this raw, real, and powerful collection of essays that explores everything from ADD to PTSD.

Have you ever felt like you just couldn’t get out of bed? Not the occasional morning, but every day? Do you find yourself listening to a voice in your head that says “you’re not good enough,” “not good looking enough,” “not thin enough,” or “not smart enough”? Have you ever found yourself unable to do homework or pay attention in class unless everything is “just so” on your desk? Everyone has had days like that, but what if you have them every day?

You’re not alone. Millions of people are going through similar things. However issues around mental health still tend to be treated as something shrouded in shame or discussed in whispers. It’s easier to have a broken bone—something tangible that can be “fixed”—than to have a mental illness, and easier to have a discussion about sex than it is to have one about mental health.

Life Inside My Mind is an anthology of true-life events from writers of this generation, for this generation. These essays tackle everything from neurodiversity to addiction to OCD to PTSD and much more. The goals of this book range from providing a home to those who are feeling alone, awareness to those who are witnessing a friend or family member struggle, and to open the floodgates to conversation.

Preț: 43.62 lei

Preț vechi: 59.03 lei

-26% Nou

Puncte Express: 65

Preț estimativ în valută:

8.35€ • 8.71$ • 6.91£

8.35€ • 8.71$ • 6.91£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781481494656

ISBN-10: 1481494651

Pagini: 320

Ilustrații: f-c matte lam cvr w- spot UV

Dimensiuni: 140 x 210 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers

Colecția Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers

ISBN-10: 1481494651

Pagini: 320

Ilustrații: f-c matte lam cvr w- spot UV

Dimensiuni: 140 x 210 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers

Colecția Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers

Notă biografică

Jessica Ashley writes under the penname Jessica Burkhart. She is the author of the Unicorn Magic and Canterwood Crest series. Visit her online at JessicaBurkhart.com.

Other contributors include E.K. Anderson, J.L. Armentrout, Cyn Balog, Amber Benson, Francesca Lia Block, Crissa Chappell, Sarah Fine, Kelly Fiore, Candace Ganger, Meghan Kelley Hall, Cynthia Hand, Ellen Hopkins, Maureen Johnson, Tara Kelly, Karen Mahoney, Melissa Marr, Kim McCreight, Hannah Moskowitz, Scott Neumyer, Lauren Oliver, Aprilynne Pike, Tom Pollack, Amy Reed, Cindy Rodriquez, Francisco Stork, Wendy Toliver, Rob Wells, Dan Wells, Rachel Wilson, and Sara Zarr.

Other contributors include E.K. Anderson, J.L. Armentrout, Cyn Balog, Amber Benson, Francesca Lia Block, Crissa Chappell, Sarah Fine, Kelly Fiore, Candace Ganger, Meghan Kelley Hall, Cynthia Hand, Ellen Hopkins, Maureen Johnson, Tara Kelly, Karen Mahoney, Melissa Marr, Kim McCreight, Hannah Moskowitz, Scott Neumyer, Lauren Oliver, Aprilynne Pike, Tom Pollack, Amy Reed, Cindy Rodriquez, Francisco Stork, Wendy Toliver, Rob Wells, Dan Wells, Rachel Wilson, and Sara Zarr.

Extras

Life Inside My Mind

![]()

by Maureen Johnson

I have had anxiety. I suffered a serious bout of it a few years ago. It hit me like a bolt out of the blue and stuck with me for a while.

If you have anxiety, you may know that reading about anxiety usually makes more anxiety. When I had anxiety, I could not read about anxiety without getting anxiety, and yet I read about it pretty compulsively, looking for answers. I was looking for something that told me there was a light at the end of the tunnel. I am letting you know that this essay has that light. It has a sunrise. I know that matters. Trust me. Hold my hand as we go, if you want to go with me.

Anxiety bouts can end. They end all the time. Never give up hope that yours can and will end. I am not a mental health professional, and if you are suffering from severe anxiety, I strongly, strongly suggest seeing one. You may already be doing so. Also, what I write about here is what happened to me. We are all different, and your mileage may vary. Anxiety has a lot of causes and pathways. There is no one way to deal with it—which is good. There are a LOT of ways. Millions—billions?—of people deal with anxiety. Almost all of us deal with some form of mental infirmity at one point or another in our lives. You’re not only not alone—you’re in the majority.

I want you to know that people can have it and do lots of stuff and actually be happy. I want you to know that exists.

I want you to know it is not all bad. I swear I am not making this up. I want you to know the bout of anxiety that I thought would crush me may have been one of the very best things that ever happened to me. It can be useful.

Now I’ll just tell you my story, and if it is of use to you, that’s good.

So what happened was that things were going pretty well for me when the anxiety hit. Before then, I thought I knew what anxiety was. I thought it was that feeling I’d had before tests, or in certain situations. I thought it was just that nervous feeling. I soon learned that anxiety was a very weird beast.

It came on first as some strange sensations—pounding in the chest, things that felt like electrical shocks going down my arms. At the time, I was working a lot. I thought nothing of sitting at my desk until midnight or later, pounding away. My brain was going and going like a train, and then these shocks would come on. It really felt like I had been hit with a bolt of juice right out of a power outlet. Then came the panic attacks in the night, when I would wake up with my heart racing, feeling like I couldn’t breathe. They got more and more frequent. Then I was often up at five a.m., pacing around. And then one day I had one of those that didn’t shut off when I woke up. My body was racing. What was most disturbing was that suddenly I didn’t feel like I was in control of my thoughts. It was like I had always been in the driver’s seat of my brain, and then one morning it was hijacked. I was shoved to the passenger’s seat. I could see where we were going, but I couldn’t steer. Almost as if I was watching myself think. I was filled with dread and energy, and I had no idea why. My brain was veering around all over the place.

This all happened on a beautiful summer’s day. I was supposed to meet two friends to write. I got myself dressed and went out. I called my mother (who is a nurse) and spoke to her. I was teary and shaking. I tried to work, but the words were moving around on the page in front of me. I told my friends what was going on, and they were very helpful. I felt like I had to walk. They walked with me for a few hours, and then one of them got in a cab with me and took me to the doctor. (The doctor had already checked me over for the symptoms I’d been having. He had concluded I had anxiety.)

I was given Ativan that night. My mother came up to stay with me—I was in that much of a state of distress. I took the pill. My system slowed down a bit for the night and kicked up again the next day. This was the start of months of this. I won’t go through the bad stuff and all the thoughts I had, because you probably already know them if you have been through it. I did wonder a lot about how I was going to do anything, how I was going to live my life and do my job. I wondered how I was going to go to bed, and then what would happen when I woke up. These are the kinds of fun times anxiety gives you. It’s a jerk. During that summer, writing was hard. I couldn’t focus very well. Then I got angry, and I attacked the anxiety. I attacked it with EVERYTHING I COULD FIND. I said, “I have decided this anxiety is a signal that I need to do something, so I am going to do it.”

Let me tell you what I learned and WHAT I DID ABOUT IT, because that is what matters.

First, the anxiety is not you. It’s drifting around you, but it’s not you. I like to imagine anxiety as the big red monster from Bugs Bunny. (Google this if you want the visual.) It sits outside you. It’s kind of ridiculous-looking. The anxiety may be with you now, but it can just as easily go away. It is not a permanent part of you, no matter how it seems.

Second thing: You know how depression lies? Well, anxiety is stupid. I did not just say people with anxiety are stupid. No, no. I mean that anxiety itself is stupid. If you asked anxiety what two plus two is, anxiety will think very hard and then say “triangle” or “a bag of Fritos” or “a commemorative stamp.” Because anxiety doesn’t know what anything is. It will try to convince you that things that are totally fine are worthy of dread. That summer, when it was bad, it didn’t matter what I looked at or engaged in at first; the anxiety monster was scared of it. It was scared of busy situations, accidents, spiders, sleeping, being awake, my sneakers, the wall . . . I caught on to the stupidity thing the day I broke down and watched the most boring nature show I could possibly find, just to slow my mind down. It was just pretty pictures of mountains and trees. An anxiety attack came on as I was watching, and I said to it, “You are totally stupid. Nothing this stupid can defeat me. You’re going down, you idiotic monster. I AM RULER HERE!”

Another helpful visual: I started to think of anxiety as being very, very small, like a child in an oversize lab coat who was trying to order me around. “You’re adorable, kid,” I said. “Now let’s go find your parents. Or maybe put you in an orphanage.”1

With that realization, anxiety was genuinely put on notice.

Third: I looked around at my life and situation. I saw a few things clearly for the first time. For a start, I had no boundaries between work and life. I had no time limits. I would stay online until all hours and let my brain drink in the electricity. There is a lot of research (so much I can’t just link here) that indicates this is not super good for our brains. I started to set limits. I stopped work at certain hours, no matter what. If the anxiety had made it hard to write during the day, I didn’t try again at night. I stopped.

I slowed down everything. I put myself on a gentler mental diet, and I didn’t care who knew it. If it was slow and boring and something that would be enjoyed in a nursing home, then it was for me. I adopted what I called the Grandma Lifestyle, and I’ve never looked back. This idea that we have to be Doing! Things! All! The! Time! is bullshit. That’s television talking to you, or articles, or the persistent but false impression that literally everyone is out accomplishing more and doing more and loving it all 100 PERCENT OF THE TIME!!! Lies. People do some things using various units of time and under all kinds of conditions. This is not a competition, and there is no metric.

I walked slowly. I went out and looked at whatever there was to see. A tree. A duck. Storefronts. Other people. I dialed it all back and stopped judging what I had to be reading/doing/thinking/appreciating and suddenly realized I had a lot of weird ideas about what I “had” to do. I’d been knocking myself around and making myself jump through hoops to accomplish things that had no discernible benefit. I didn’t learn this in one day. It took a few months. My thoughts began to clear, and I was able to do more and more. And a major part of the way I got there was through meditation.

That’s four: meditation. And it is a BIG ONE. I know. It’s in magazines at Whole Foods and it’s everywhere and trendy, but you know what? It changed my life, and I do it every day. Again, plenty of science out there you can easily find online. You need to be consistent. This is the key. You don’t just do it once and then you’re changed. It is like exercise. I tell you true I know it changed my way of thinking and has probably physically changed my brain. It is part of my life to this day and will remain so.2

Five: I got help. I went to the doctor and got medication that I was on for about a year and a half, and I did cognitive behavioral therapy, which helped me break down my thought patterns. I also had a more serious look at WHY I was so burned-out and exhausted and found the medical problem that was really at the root of all of this. Which was a good thing. I mean, it’s annoying, but it’s good to know, because I can do something about it.

Six: I exercised. I started going to yoga classes a lot. Which, again, seems like a cliché but does in fact work. I walked. I just moved. I also cut back on caffeine a tremendous amount. I had been drinking QUITE A LOT OF COFFEE up until that point. (I probably could do five to eight cups a day.) I stopped entirely for about two years. Now I drink a limited amount and never in the evening. So yes, sensible diet and sensible steps that are all boring but REALLY WORK. But they work over time.

Seven: KNOW THAT IT CAN END. It will tell you that it won’t. Remember: IT DOESN’T KNOW ANYTHING. Anxiety is like a four-year-old who thinks they are a surgeon—that’s cute that the child thinks that, but you wouldn’t actually let the four-year-old operate on you. THE CHILD KNOWS NOTHING. You would prevent the child from attempting any surgical procedure. Likewise, anxiety must be prevented from making your decisions. It’s so small! It’s so silly! Look how it thinks it can move you around! You can regain control. It really isn’t stronger than you.

Eight: I found out just how many other people had it. Seeing it was not just me really was a great eye-opener. Someone around you has anxiety right now as well. You may or may not know about it. People doing all kinds of things have anxiety. Some of the people who make the shows you like have or had it. Same with the people who write the songs you like or the books you like. People doing all kinds of jobs have or had it. It is super common. It moves around. It can be lived with and shown the door. You are not alone in this.

Nine: There is nothing to be embarrassed about. So what if you are hiding in a bathroom stall because you’ve panicked about seeing a menu? SO WHAT. So what if you are talking fast? SO WHAT. So what if you wrote a long and nervous-sounding post? SO WHAT. So what if you couldn’t finish something because you had an anxiety attack while looking at a pen? SO WHAT. Doesn’t matter. I’ve been there. Come on out when you’re ready, and we’ll throw that pen out the window. Or we’ll say, “It’s okay—you’re a nice pen.” SO WHAT. Say SO WHAT right now. Because SO WHAT. Unless you just caused a major international incident, which I promise you you did not (unless you are Vladimir Putin reading this, in which case I have severely misjudged my audience), you didn’t do anything awful and no one cares and SO WHAT!

I had to throw a whole bunch of stuff at it. Together, it worked. The severe, continuous bouts stopped after a few months. I remained on alert for at least a year or two, but I genuinely cannot remember if I had attacks during that time. Because part of what happened was that I stopped being afraid of it. I gave it permission to come and go. I left the door open. “You can come in,” I said, “and you can show yourself out.” Sounds stupid and New Agey, but it is a TRUE STATEMENT. I just decided I didn’t care anymore and was going to go about my business whether it was there or not. It took effort, but I stuck with that. And the monster wandered off on its stupid way.

But I don’t hate it. Remember I said there was good stuff? There was.

I’m frankly a better person for having had it. I’m not saying I am a fantastic person—that is not for me to decide. But I felt the sting, and I got a lot more compassionate. I realized that since I had this major disruption, I might as well use the time to make some changes. It’s like, Well, the roof of my house just came off. I guess I’ll redecorate! This is possible. You can make it do something for you, since it is there. Give that stupid monster a broom and MAKE IT CLEAN. I slowed the hell down, and I like stuff more now. I give no f**ks about what people think of my slow-life choices.

When I did this, I looked around at what I had and saw that life is pretty great and things can change. I thought I couldn’t do anything when I had it, and I look back and see that I did lots of things. Was I slower? Yes. But do I still get my stuff done? Yes. I work more efficiently now.

I realized that when I wasn’t staring at the anxiety all the time, I was happy. I had convinced myself for a while that it was not possible to be both, but that’s a lie. You may think that is true because the anxiety is dancing around like a big dumb idiot, trying to block your view of happy. But happy can be there. It probably is there. CONTENT is there. NON-ANXIETY is definitely there.

Again, this is my story, and all the stories are different. But like I said, I tell this one to give you a true story about having anxiety that ends with something good, which happens to be true. A lot of you are going to deal with it, and you can make that stupid monster dance. You can make good changes. Or you can just be okay. You can. Don’t listen to it when it tells you you can’t, because remember: It is stupid and you are not. It doesn’t know a thing. It really doesn’t. Whatever happens, SO WHAT.

Good luck out there, and give no f**ks you do not want to give.

1 I do not condone putting misbehaving children into orphanages, unless they are imaginary misbehaving children who live in your head. And my imaginary orphanage for imaginary children is a very nice place.

2 I have taken several types of meditation classes or programs in the last few years. I really went for it. The ones I recommend most are mindfulness-based stress reduction (often labeled as MBSR) classes. There are also free or quite cheap apps available, and loads of places offer free or very cheap classes. Have a look around your area. Many libraries will have books on meditation as well. There is no bad way to get started, and it is often worth trying a few things to see what works for you.

Stupid Monsters and Child Surgeons

by Maureen Johnson

I have had anxiety. I suffered a serious bout of it a few years ago. It hit me like a bolt out of the blue and stuck with me for a while.

If you have anxiety, you may know that reading about anxiety usually makes more anxiety. When I had anxiety, I could not read about anxiety without getting anxiety, and yet I read about it pretty compulsively, looking for answers. I was looking for something that told me there was a light at the end of the tunnel. I am letting you know that this essay has that light. It has a sunrise. I know that matters. Trust me. Hold my hand as we go, if you want to go with me.

Anxiety bouts can end. They end all the time. Never give up hope that yours can and will end. I am not a mental health professional, and if you are suffering from severe anxiety, I strongly, strongly suggest seeing one. You may already be doing so. Also, what I write about here is what happened to me. We are all different, and your mileage may vary. Anxiety has a lot of causes and pathways. There is no one way to deal with it—which is good. There are a LOT of ways. Millions—billions?—of people deal with anxiety. Almost all of us deal with some form of mental infirmity at one point or another in our lives. You’re not only not alone—you’re in the majority.

I want you to know that people can have it and do lots of stuff and actually be happy. I want you to know that exists.

I want you to know it is not all bad. I swear I am not making this up. I want you to know the bout of anxiety that I thought would crush me may have been one of the very best things that ever happened to me. It can be useful.

Now I’ll just tell you my story, and if it is of use to you, that’s good.

So what happened was that things were going pretty well for me when the anxiety hit. Before then, I thought I knew what anxiety was. I thought it was that feeling I’d had before tests, or in certain situations. I thought it was just that nervous feeling. I soon learned that anxiety was a very weird beast.

It came on first as some strange sensations—pounding in the chest, things that felt like electrical shocks going down my arms. At the time, I was working a lot. I thought nothing of sitting at my desk until midnight or later, pounding away. My brain was going and going like a train, and then these shocks would come on. It really felt like I had been hit with a bolt of juice right out of a power outlet. Then came the panic attacks in the night, when I would wake up with my heart racing, feeling like I couldn’t breathe. They got more and more frequent. Then I was often up at five a.m., pacing around. And then one day I had one of those that didn’t shut off when I woke up. My body was racing. What was most disturbing was that suddenly I didn’t feel like I was in control of my thoughts. It was like I had always been in the driver’s seat of my brain, and then one morning it was hijacked. I was shoved to the passenger’s seat. I could see where we were going, but I couldn’t steer. Almost as if I was watching myself think. I was filled with dread and energy, and I had no idea why. My brain was veering around all over the place.

This all happened on a beautiful summer’s day. I was supposed to meet two friends to write. I got myself dressed and went out. I called my mother (who is a nurse) and spoke to her. I was teary and shaking. I tried to work, but the words were moving around on the page in front of me. I told my friends what was going on, and they were very helpful. I felt like I had to walk. They walked with me for a few hours, and then one of them got in a cab with me and took me to the doctor. (The doctor had already checked me over for the symptoms I’d been having. He had concluded I had anxiety.)

I was given Ativan that night. My mother came up to stay with me—I was in that much of a state of distress. I took the pill. My system slowed down a bit for the night and kicked up again the next day. This was the start of months of this. I won’t go through the bad stuff and all the thoughts I had, because you probably already know them if you have been through it. I did wonder a lot about how I was going to do anything, how I was going to live my life and do my job. I wondered how I was going to go to bed, and then what would happen when I woke up. These are the kinds of fun times anxiety gives you. It’s a jerk. During that summer, writing was hard. I couldn’t focus very well. Then I got angry, and I attacked the anxiety. I attacked it with EVERYTHING I COULD FIND. I said, “I have decided this anxiety is a signal that I need to do something, so I am going to do it.”

Let me tell you what I learned and WHAT I DID ABOUT IT, because that is what matters.

First, the anxiety is not you. It’s drifting around you, but it’s not you. I like to imagine anxiety as the big red monster from Bugs Bunny. (Google this if you want the visual.) It sits outside you. It’s kind of ridiculous-looking. The anxiety may be with you now, but it can just as easily go away. It is not a permanent part of you, no matter how it seems.

Second thing: You know how depression lies? Well, anxiety is stupid. I did not just say people with anxiety are stupid. No, no. I mean that anxiety itself is stupid. If you asked anxiety what two plus two is, anxiety will think very hard and then say “triangle” or “a bag of Fritos” or “a commemorative stamp.” Because anxiety doesn’t know what anything is. It will try to convince you that things that are totally fine are worthy of dread. That summer, when it was bad, it didn’t matter what I looked at or engaged in at first; the anxiety monster was scared of it. It was scared of busy situations, accidents, spiders, sleeping, being awake, my sneakers, the wall . . . I caught on to the stupidity thing the day I broke down and watched the most boring nature show I could possibly find, just to slow my mind down. It was just pretty pictures of mountains and trees. An anxiety attack came on as I was watching, and I said to it, “You are totally stupid. Nothing this stupid can defeat me. You’re going down, you idiotic monster. I AM RULER HERE!”

Another helpful visual: I started to think of anxiety as being very, very small, like a child in an oversize lab coat who was trying to order me around. “You’re adorable, kid,” I said. “Now let’s go find your parents. Or maybe put you in an orphanage.”1

With that realization, anxiety was genuinely put on notice.

Third: I looked around at my life and situation. I saw a few things clearly for the first time. For a start, I had no boundaries between work and life. I had no time limits. I would stay online until all hours and let my brain drink in the electricity. There is a lot of research (so much I can’t just link here) that indicates this is not super good for our brains. I started to set limits. I stopped work at certain hours, no matter what. If the anxiety had made it hard to write during the day, I didn’t try again at night. I stopped.

I slowed down everything. I put myself on a gentler mental diet, and I didn’t care who knew it. If it was slow and boring and something that would be enjoyed in a nursing home, then it was for me. I adopted what I called the Grandma Lifestyle, and I’ve never looked back. This idea that we have to be Doing! Things! All! The! Time! is bullshit. That’s television talking to you, or articles, or the persistent but false impression that literally everyone is out accomplishing more and doing more and loving it all 100 PERCENT OF THE TIME!!! Lies. People do some things using various units of time and under all kinds of conditions. This is not a competition, and there is no metric.

I walked slowly. I went out and looked at whatever there was to see. A tree. A duck. Storefronts. Other people. I dialed it all back and stopped judging what I had to be reading/doing/thinking/appreciating and suddenly realized I had a lot of weird ideas about what I “had” to do. I’d been knocking myself around and making myself jump through hoops to accomplish things that had no discernible benefit. I didn’t learn this in one day. It took a few months. My thoughts began to clear, and I was able to do more and more. And a major part of the way I got there was through meditation.

That’s four: meditation. And it is a BIG ONE. I know. It’s in magazines at Whole Foods and it’s everywhere and trendy, but you know what? It changed my life, and I do it every day. Again, plenty of science out there you can easily find online. You need to be consistent. This is the key. You don’t just do it once and then you’re changed. It is like exercise. I tell you true I know it changed my way of thinking and has probably physically changed my brain. It is part of my life to this day and will remain so.2

Five: I got help. I went to the doctor and got medication that I was on for about a year and a half, and I did cognitive behavioral therapy, which helped me break down my thought patterns. I also had a more serious look at WHY I was so burned-out and exhausted and found the medical problem that was really at the root of all of this. Which was a good thing. I mean, it’s annoying, but it’s good to know, because I can do something about it.

Six: I exercised. I started going to yoga classes a lot. Which, again, seems like a cliché but does in fact work. I walked. I just moved. I also cut back on caffeine a tremendous amount. I had been drinking QUITE A LOT OF COFFEE up until that point. (I probably could do five to eight cups a day.) I stopped entirely for about two years. Now I drink a limited amount and never in the evening. So yes, sensible diet and sensible steps that are all boring but REALLY WORK. But they work over time.

Seven: KNOW THAT IT CAN END. It will tell you that it won’t. Remember: IT DOESN’T KNOW ANYTHING. Anxiety is like a four-year-old who thinks they are a surgeon—that’s cute that the child thinks that, but you wouldn’t actually let the four-year-old operate on you. THE CHILD KNOWS NOTHING. You would prevent the child from attempting any surgical procedure. Likewise, anxiety must be prevented from making your decisions. It’s so small! It’s so silly! Look how it thinks it can move you around! You can regain control. It really isn’t stronger than you.

Eight: I found out just how many other people had it. Seeing it was not just me really was a great eye-opener. Someone around you has anxiety right now as well. You may or may not know about it. People doing all kinds of things have anxiety. Some of the people who make the shows you like have or had it. Same with the people who write the songs you like or the books you like. People doing all kinds of jobs have or had it. It is super common. It moves around. It can be lived with and shown the door. You are not alone in this.

Nine: There is nothing to be embarrassed about. So what if you are hiding in a bathroom stall because you’ve panicked about seeing a menu? SO WHAT. So what if you are talking fast? SO WHAT. So what if you wrote a long and nervous-sounding post? SO WHAT. So what if you couldn’t finish something because you had an anxiety attack while looking at a pen? SO WHAT. Doesn’t matter. I’ve been there. Come on out when you’re ready, and we’ll throw that pen out the window. Or we’ll say, “It’s okay—you’re a nice pen.” SO WHAT. Say SO WHAT right now. Because SO WHAT. Unless you just caused a major international incident, which I promise you you did not (unless you are Vladimir Putin reading this, in which case I have severely misjudged my audience), you didn’t do anything awful and no one cares and SO WHAT!

I had to throw a whole bunch of stuff at it. Together, it worked. The severe, continuous bouts stopped after a few months. I remained on alert for at least a year or two, but I genuinely cannot remember if I had attacks during that time. Because part of what happened was that I stopped being afraid of it. I gave it permission to come and go. I left the door open. “You can come in,” I said, “and you can show yourself out.” Sounds stupid and New Agey, but it is a TRUE STATEMENT. I just decided I didn’t care anymore and was going to go about my business whether it was there or not. It took effort, but I stuck with that. And the monster wandered off on its stupid way.

But I don’t hate it. Remember I said there was good stuff? There was.

I’m frankly a better person for having had it. I’m not saying I am a fantastic person—that is not for me to decide. But I felt the sting, and I got a lot more compassionate. I realized that since I had this major disruption, I might as well use the time to make some changes. It’s like, Well, the roof of my house just came off. I guess I’ll redecorate! This is possible. You can make it do something for you, since it is there. Give that stupid monster a broom and MAKE IT CLEAN. I slowed the hell down, and I like stuff more now. I give no f**ks about what people think of my slow-life choices.

When I did this, I looked around at what I had and saw that life is pretty great and things can change. I thought I couldn’t do anything when I had it, and I look back and see that I did lots of things. Was I slower? Yes. But do I still get my stuff done? Yes. I work more efficiently now.

I realized that when I wasn’t staring at the anxiety all the time, I was happy. I had convinced myself for a while that it was not possible to be both, but that’s a lie. You may think that is true because the anxiety is dancing around like a big dumb idiot, trying to block your view of happy. But happy can be there. It probably is there. CONTENT is there. NON-ANXIETY is definitely there.

Again, this is my story, and all the stories are different. But like I said, I tell this one to give you a true story about having anxiety that ends with something good, which happens to be true. A lot of you are going to deal with it, and you can make that stupid monster dance. You can make good changes. Or you can just be okay. You can. Don’t listen to it when it tells you you can’t, because remember: It is stupid and you are not. It doesn’t know a thing. It really doesn’t. Whatever happens, SO WHAT.

Good luck out there, and give no f**ks you do not want to give.

1 I do not condone putting misbehaving children into orphanages, unless they are imaginary misbehaving children who live in your head. And my imaginary orphanage for imaginary children is a very nice place.

2 I have taken several types of meditation classes or programs in the last few years. I really went for it. The ones I recommend most are mindfulness-based stress reduction (often labeled as MBSR) classes. There are also free or quite cheap apps available, and loads of places offer free or very cheap classes. Have a look around your area. Many libraries will have books on meditation as well. There is no bad way to get started, and it is often worth trying a few things to see what works for you.

Recenzii

Ellen Hopkins, Lauren Oliver, Francisco X. Stork, Sara Zarr, and the other 27 contributors to this anthology are all best-selling, award-winning authors. Yet many admit that their personal essay on mental illness was the hardest piece they’ve ever written. Although a few authors write about friends and family, most reveal their own struggles with anxiety, depression, addiction, OCD, ADHD, PTSD, bipolar disorder, body-image issues, and more, with cutting and suicidal thoughts often entering the picture. The contributors explain how the mental illness first manifested itself and eventually took over their lives. Their essays (and one poem) are raw, intense, and poignant. Individually, they show a wide range of experiences; collectively, they show commonalities among sufferers. There are feelings of isolation, shame, being stigmatized, and losing control as “it” or a “monster” seemingly guides their thoughts and actions. Nevertheless, hope and recovery also shine through as the authors reflect on their self-care and coping mechanisms, including therapy, medication, meditation, exercise, sleep, and diet. Just like mental illness itself, the paths to acceptance and recovery take many forms. Who better to raise teens’ awareness of mental illness and health than the YA authors they admire? Their compelling stories will start important discussions and assure readers they’re never alone. — Angela Leeper

Teens may be unlikely to seek out this collection on their own, but it is a valuable read to put in the hands of those who need it. (Memoir/essay. 14-18)

Renowned writers of fiction and nonfiction candidly speak out about their experiences with often stigmatized mental illnesses, including agoraphobia, OCD, Alzheimer’s, bipolar disorder, PTSD, and depression and anxiety, which frequently go hand in hand. Some of the authors focus on what it is like to be in their shoes, such as editor-poet E.K. Anderson, who expresses her experience with bipolar disorder entirely in verse, and Megan Kelley Hall, who details her suffering in her essay “My Depression—A Rock and a Hard Place.” More often than not, however, the aims of the authors—who include Ellen Hopkins, Francisco X. Stork, Maureen Johnson, Sara Zarr, and many others—are to help readers, advising them on where to turn for help and advocating for a society that is more sensitive and informed about mental and emotional health. Author Tara Kelly provides a concrete list of tips ranging from medication to stargazing to help relieve symptoms of acute anxiety. These bold, brave essays will educate the uninformed and inspire hope in those who may feel alone in their suffering.

In this collection of personal essays, thirty-one authors of children’s and young adult literature (including well-known names such as Hannah Moskowitz, Francisco X. Stork, and Francesca Lia Block) reveal their struggles with anxiety, depression, compulsions to self-harm, suicidal ideations, and other mental conditions and disorders. A few discuss their experiences with close others who are suffering, but most describe in detail what their own good and bad days are like. Some use evocative metaphors and images, while others are quite literal, and nearly all describe the therapies and strategies that they have found effective while highlighting that there are no easy, permanent, or one-size-fits-all solutions. Most of the essays are explicitly directive in encouraging readers to seek help, and comforting in the authors’ insistence that seemingly abnormal mental conditions are in fact more prevalent than one might realize and certainly survivable given proper treatment. The individuality of the approaches does tend to constitute such problems as being entirely intrapsychic, since there’s no talk of wider social conditions that require activist rather than merely therapeutic solutions. For teens who are suffering, though, these authors prove that, with the help of friends, professionals, and/or the right combination of meds, people with mental health issues can flourish, attain success, and help others by sharing their stories, whether personal or creative.

From anxiety attacks and depression to obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), bipolar disorder, and drug and alcohol addiction, each of the authors (many of whom teens will recognize) pens an essay describing their experiences with mental illness. Some write of their suicidal tendencies; others share their struggles with ADHD. Authors describe such issues as how they learn to recognize the symptoms that signal a recurrence of their symptoms, and how they employ coping mechanisms that enable them to continue with their lives. These include medication and therapy, yoga, exercise, meditation, and help from health professionals. Other writers describe what it is like to care for a loved one with mental illness: Dan Wells caring for a beloved grandfather with Alzheimer’s, Ellen Hopkins bringing up a grandson damaged by early childhood trauma, and a mother interviewing her sixteen-year-old son in order to show that others who are depressed and have OCD are not alone. Cindy L. Rodriguez writes about cultural issues regarding the Latinx community and the treatment of mental illness.

Importantly, this book emphasizes that many people live with mental health issues and that, despite the ignorance about and negativity toward mental illness, there is nothing of which they should be ashamed. Writers of these essays offer support by demonstrating that they are survivors who are willing to acknowledge and discuss their different illnesses. These are important messages to make available to teens.

Gr 9 Up–In this much-needed, enlightening book, 31 young adult authors write candidly about mental health crises, either their own or that of someone very close to them. Ranging from humorous to heartbreaking to hopeful, each story has a uniquely individual approach to the set of circumstances that the writer is dealing with. Many authors address readers in the second person, inviting them to imagine what it’s like to live a day inside their heads. The symptoms of anxiety, depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and addiction are frequently discussed. Readers will learn of the many different ways these conditions can be present and in which they often work together. Despite the intense emotional content, teens will warm to the authenticity apparent in every voice. Many, if not most of the essays offer a list of the techniques and treatments that have been successful in handling symptoms, including medication, therapy, exercise, and yoga. The difficulty in recognizing mental health issues, as well as the unfortunate stigma associated with asking for help, is frequently acknowledged and may help teen and adult readers work toward achieving a more open dialogue. Perhaps most importantly, the collection’s overarching sentiment points toward acceptance and the idea that treatment is a journey. As contributor Tara Kelly writes: “If anxiety gets the better of me again, that’s okay. I give myself permission to fall down and get back up.” VERDICT A first purchase for all young adult collections.–Kristy Pasquariello, Wellesley Free Library, MA

Teens may be unlikely to seek out this collection on their own, but it is a valuable read to put in the hands of those who need it. (Memoir/essay. 14-18)

Renowned writers of fiction and nonfiction candidly speak out about their experiences with often stigmatized mental illnesses, including agoraphobia, OCD, Alzheimer’s, bipolar disorder, PTSD, and depression and anxiety, which frequently go hand in hand. Some of the authors focus on what it is like to be in their shoes, such as editor-poet E.K. Anderson, who expresses her experience with bipolar disorder entirely in verse, and Megan Kelley Hall, who details her suffering in her essay “My Depression—A Rock and a Hard Place.” More often than not, however, the aims of the authors—who include Ellen Hopkins, Francisco X. Stork, Maureen Johnson, Sara Zarr, and many others—are to help readers, advising them on where to turn for help and advocating for a society that is more sensitive and informed about mental and emotional health. Author Tara Kelly provides a concrete list of tips ranging from medication to stargazing to help relieve symptoms of acute anxiety. These bold, brave essays will educate the uninformed and inspire hope in those who may feel alone in their suffering.

In this collection of personal essays, thirty-one authors of children’s and young adult literature (including well-known names such as Hannah Moskowitz, Francisco X. Stork, and Francesca Lia Block) reveal their struggles with anxiety, depression, compulsions to self-harm, suicidal ideations, and other mental conditions and disorders. A few discuss their experiences with close others who are suffering, but most describe in detail what their own good and bad days are like. Some use evocative metaphors and images, while others are quite literal, and nearly all describe the therapies and strategies that they have found effective while highlighting that there are no easy, permanent, or one-size-fits-all solutions. Most of the essays are explicitly directive in encouraging readers to seek help, and comforting in the authors’ insistence that seemingly abnormal mental conditions are in fact more prevalent than one might realize and certainly survivable given proper treatment. The individuality of the approaches does tend to constitute such problems as being entirely intrapsychic, since there’s no talk of wider social conditions that require activist rather than merely therapeutic solutions. For teens who are suffering, though, these authors prove that, with the help of friends, professionals, and/or the right combination of meds, people with mental health issues can flourish, attain success, and help others by sharing their stories, whether personal or creative.

From anxiety attacks and depression to obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), bipolar disorder, and drug and alcohol addiction, each of the authors (many of whom teens will recognize) pens an essay describing their experiences with mental illness. Some write of their suicidal tendencies; others share their struggles with ADHD. Authors describe such issues as how they learn to recognize the symptoms that signal a recurrence of their symptoms, and how they employ coping mechanisms that enable them to continue with their lives. These include medication and therapy, yoga, exercise, meditation, and help from health professionals. Other writers describe what it is like to care for a loved one with mental illness: Dan Wells caring for a beloved grandfather with Alzheimer’s, Ellen Hopkins bringing up a grandson damaged by early childhood trauma, and a mother interviewing her sixteen-year-old son in order to show that others who are depressed and have OCD are not alone. Cindy L. Rodriguez writes about cultural issues regarding the Latinx community and the treatment of mental illness.

Importantly, this book emphasizes that many people live with mental health issues and that, despite the ignorance about and negativity toward mental illness, there is nothing of which they should be ashamed. Writers of these essays offer support by demonstrating that they are survivors who are willing to acknowledge and discuss their different illnesses. These are important messages to make available to teens.

Gr 9 Up–In this much-needed, enlightening book, 31 young adult authors write candidly about mental health crises, either their own or that of someone very close to them. Ranging from humorous to heartbreaking to hopeful, each story has a uniquely individual approach to the set of circumstances that the writer is dealing with. Many authors address readers in the second person, inviting them to imagine what it’s like to live a day inside their heads. The symptoms of anxiety, depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and addiction are frequently discussed. Readers will learn of the many different ways these conditions can be present and in which they often work together. Despite the intense emotional content, teens will warm to the authenticity apparent in every voice. Many, if not most of the essays offer a list of the techniques and treatments that have been successful in handling symptoms, including medication, therapy, exercise, and yoga. The difficulty in recognizing mental health issues, as well as the unfortunate stigma associated with asking for help, is frequently acknowledged and may help teen and adult readers work toward achieving a more open dialogue. Perhaps most importantly, the collection’s overarching sentiment points toward acceptance and the idea that treatment is a journey. As contributor Tara Kelly writes: “If anxiety gets the better of me again, that’s okay. I give myself permission to fall down and get back up.” VERDICT A first purchase for all young adult collections.–Kristy Pasquariello, Wellesley Free Library, MA