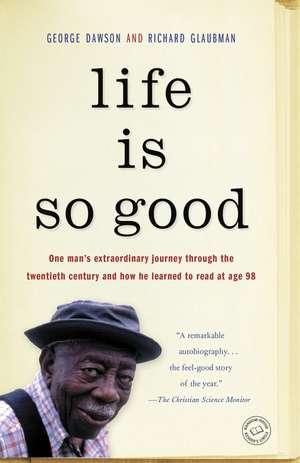

Life Is So Good: The Untold Story of the American Women Trapped on Bataan

Autor George Dawsonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 22 mai 2013 – vârsta de la 18 ani

“Things will be all right. People need to hear that. Life is good, just as it is. There isn’t anything I would change about my life.”—George Dawson

In this remarkable book, George Dawson, a slave’s grandson who learned to read at age 98 and lived to the age of 103, reflects on his life and shares valuable lessons in living, as well as a fresh, firsthand view of America during the entire sweep of the twentieth century. Richard Glaubman captures Dawson’s irresistible voice and view of the world, offering insights into humanity, history, hardships, and happiness. From segregation and civil rights, to the wars and the presidents, to defining moments in history, George Dawson’s description and assessment of the last century inspires readers with the message that has sustained him through it all: “Life is so good. I do believe it’s getting better.”

WINNER OF THE CHRISTOPHER AWARD

“A remarkable autobiography . . . . the feel-good story of the year.”—The Christian Science Monitor

“A testament to the power of perseverance.”—USA Today

“Life Is So Good is about character, soul and spirit. . . . The pride in standing his ground is matched—maybe even exceeded—by the accomplishment of [George Dawson’s] hard-won education.”—The Washington Post

“Eloquent . . . engrossing . . . an astonishing and unforgettable memoir.”—Publishers Weekly

Look for special features inside. Join the Circle for author chats and more.

Preț: 94.66 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 142

Preț estimativ în valută:

18.11€ • 18.96$ • 14.99£

18.11€ • 18.96$ • 14.99£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 17-31 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780812984873

ISBN-10: 0812984870

Pagini: 288

Dimensiuni: 135 x 206 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: Random House Trade

ISBN-10: 0812984870

Pagini: 288

Dimensiuni: 135 x 206 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: Random House Trade

Notă biografică

George Dawson lives in Dallas, Texas.

Richard Glaubman is an elementary school teacher. He lives outside Seattle, Washington.

Richard Glaubman is an elementary school teacher. He lives outside Seattle, Washington.

Extras

Wanting to enjoy every moment, I stared at the hard candies in the different wooden barrels. The man behind the counter was white. I could tell he didn't like me, so I let him see the penny in my hand.

"Take your time, son," my father said with a grin. "You did a man's work this year."

Putting his hand on my shoulder, he said to the store clerk, "He's all of ten years, but the boy crushed as much cane as I did." Since the age of four, I had always been working to help the family.

I don't know if it was pride from Father's words or the pleasure from a piece of hard candy that beckoned, but I felt so good I thought I would burst. I had been thinking of those hard candies since my father woke me before daybreak and said, "Hitch the wagon. We gonna take some ribbon syrup into town and you comin'."

When I went back inside, the stove was going and Ma had a pot of mush cooling. We ate quiet-like so as not to wake the little ones that were asleep on the other side of the room.

I was happy to see they was still sleeping for it was uncommon to spend the day alone with my father. We never had much time to talk and I just liked to be with him.

Two barrels of cane syrup were tied down in the wagon. We sat up front. My father clucked toward the mule. I wanted to tell him that I was glad he was taking me and it was going to be just him and me together all day. Trouble was, I didn't know how to say that in words. So under the shadow of my straw hat, I just looked over at him.

Solid is what I would say. He took care of us. We had potatoes and carrots buried in the straw and salt pork hangin' from the rafters. We was free of worries. Papa was a good provider. Someday I would be just like him.

Must have been a couple of hours toward town when my father nudged me. He handed me the reins and unwrapped some burlap. I took a piece of cornbread with a big dab of lard on it. When I commenced to eat, he started talking.

"With this ribbon syrup, we be out of debt and have some left for trading. We gonna have seeds for cotton, some new banty chicks, and the fruit trees that are gonna bear fruit next year. No one has the fever and we all be healthy.

"Life is good." And with a grin, he added, "I do believe it's getting better." I liked it when Papa talked to me as a man.

The morning haze had long ago burned off. The wagon stirred up a lot of dust that kind of settled over everything in a nice, smooth blanket. It was good for the mule as the dust had a way of keeping the flies off. Nothing else was said for the next hour, till we came around the last stand of trees and to the rise above Marshall.

In those days, I had in my mind that Marshall was maybe about the biggest and the best place there could ever be. The hardware store had big windows that I liked to look in. I had never been inside since I knew they didn't appreciate black folks with no money. I was partial to the general store, but I liked to walk by the livery stable too. Once a man gave me two bits to rub down and watch his horse for the afternoon. It was 1908, and I hadn't yet seen a car. I had heard of them, but nobody I knew owned one. Papa said that they didn't do too well when the rains came and the roads was deep in mud. Besides, they scared the horses. Mostly, I just liked seeing all the folks from the big ranches and the little farms like ours that was out on the boardwalk.

The cafe and the barbershop was whites only, but I knew a boy that worked in the cafe. And I knew some folks that shined shoes at the barbershop. I liked to look in those windows too.

We never had no cause to go into the post office. But I pictured that one day someone would say there was a letter waiting for me. I would walk past all the folks sitting in the town square beneath the big oak tree. When I was inside, I would say, "I'm George Dawson. I'm here to get my letter." I don't know when that was gonna happen but maybe someday it would. Marshall was a busy place and good things could just happen. It was the county seat and that had to count for something too. At least, that's what I thought then.

But at that moment, in the general store, when my father told me that I could do a man's work, anything seemed possible. I remember everything. I saw the white man frowning, my father grinning at me, and those barrels of candy to choose from. I also remember everything my ears told me that day.

As I picked up a piece of peppermint, I heard a commotion from the street. My father's gaze followed mine. It was dark and cool in the store and the hot light through the doors caused a confusing picture. There were people running, harsh words, and a lot of shouting. Papa set down a kerosene lamp he was inspecting on the counter and run to the door. I followed with the counterman behind me.

At first, out on the boardwalk, in the bright sunlight, I couldn't see the faces on the street. I heard Pete's voice before I saw him.

"It wasn't me. I didn't touch her," Pete screamed. "Lord, let me go."

I would of backed off from what I saw, but by then we was crowded up against the rail. First time in my life I saw the white folks and the colored folks together in a crowd.

It scared me. There was no more frown on the face of the white counterman that was beside of me. His lips were set in a smile. Hate was in his eyes. Across the street, in front of the barbershop, I saw three colored men frozen in place. The white folks surrounding them had red, twisted faces.

They were screaming. I had done nothing, but I felt them screaming at me.

"Kill the nigger boy, kill the nigger. They can't be messing with our white women."

Six men had Pete by the arms. The toes of his boots dragged in the dust. His face looked up to the sky as he screamed, "I didn't touch her."

I knew Pete and knew that was so. I shouted, "Pete, I'll tell-"

My father's hand clamped over my mouth. His other arm crushed the air right out of my chest. I read his eyes and then he slowly let me go without saying a word. I knew it wasn't so, though. The Riley's cook had heard the whole thing; she just kept on working in the kitchen and watched Betty Jo and her father. She was right there, but they didn't even notice she was alive.

She was scared about what they said and I heard her talking to my mama about it. Betty Jo had gotten herself in trouble. Folks already knew that she had a thing for one of the Jackson boys and was spending a lot of time with him. When her daddy found out she was with a child, she had a whipping coming sure enough. Her daddy was steaming mad and of short temper anyhow.

"Who's the boy that done this to you?" her daddy shouted. Sally looked at the belt in his hand. She was crying but wouldn't say nothing. She was scared, and afraid to tell the boy's name, because she figured that her daddy just might go off and kill him.

"Well, if you did this 'cause you wanted to, a good beating will teach you right."

She cried even harder then.

"Well, you got it coming unless maybe this happened against your will."

Her crying slowed and seeing a way out of a beating she listened close.

"Is that what happened?" he said slowly.

Scared as she was, Betty Jo could tell that the safe answer was yes. Not wanting to tell a whole lie, she just nodded her head.

"Damn. Was it that Jackson boy from across the ridge?"

Betty Jo, she loved him, or at least thought she did, shook her head no.

Her daddy looked at her hard. His face turned angry and he said, "Was it our hired boy, Pete? That worthless, lazy nigger! Did he rape you? Did he do this?"

To each question, she just nodded in the smallest way. The tears still flowed, but he threw the belt down and stormed out the door.

"There is one nigger gonna pay for this."

Pete was seventeen and the hired boy around their farm; picking cotton, cutting cane, chores like that. He was a good worker. But he was smart and he knew enough not to even look at a white woman.

I knew Pete since we were little. He was older than me, but he treated me well. Pete was the one who swum out and saved Jimmy Blake at the swimming hole. Jimmy had smacked his head on the corner of the raft when he was showing off for us little kids. Everyone was afraid to swim out that far, but he done it. Pete, he would do anything for anybody.

As I was growing up, I didn't have any toys, but I did still own a baseball that Pete had given me a year earlier. We had been at the pasture of a Sunday afternoon last summer. I had helped to cut the field. A team from Tyler had come over to play some of our boys from Marshall. We didn't have a real stadium, but we would go out and mow the pasture, and set up table for a big Sunday feast and get together afterward. Pete played shortstop. He was good too. If you wanted fast, you should have seen Pete run the bases.

The score was tied and went to extra innings. In the eleventh Pete came up with a man on first, two outs. He took their pitcher full count. And then ... and then he almost hit a cow. It would of been a home run if we had fences. As it was, he got a triple and drove in the winning run. I cheered and cheered for our Marshall boys, especially for Pete.

I was proud of him when the team gave him the game ball. He gave me that ball and said, "You practice with it, George. You'll be a hitter someday too." I was awful pleased but I could barely mutter thank you when my mama nudged me. Pete was my hero.

The colored couldn't play in the big leagues, but if they could I know Pete would of made it.

Yeah, someone had committed a sin and Pete was gonna pay for it. I looked down the boardwalk. They was dragging Pete in the direction of the post office. Sheriff Tate stepped off the boardwalk up ahead from where the mob was. I let out a big breath of air. The sheriff was a big man. I had heard it said that, on a bet, he had carried a barrel of molasses on his back from the general store down past the saloon. They say that once when things got out of hand at the rodeo and the crowd threatened an official, the sheriff took care of it himself. He laid six men out cold before the crowd settled down. I knew he could stop this. People was spilling off the boardwalk and cursing Pete something terrible.

"We gonna keep our women safe."

"Make that boy pay and show all the niggers that they can't get away with this."

Pete was kicking and thrashing, but the mob was still hauling him farther down the street. Taking a few steps along the edge of the road, the sheriff stopped. He kicked the dust and planted his feet. He had big, shiny-looking boots that dust didn't want to stick to. His pants, tucked into the boots, had a stripe down the sides. A big pistol hung off his belt. He pulled the pistol out and crossed his arms so that the pistol set against his chest.

He turned and looked back toward the boardwalk. The sheriff was in front of a group of colored that was pressed into the crowd. He scowled and sent them a message that gave me a chill on a hot day. I had heard tell that the sheriff ran with the Klan at night when they would come through the colored section or out to the colored farms. They would leave a burning cross or shoot some windows out. That's what people said about him and now I knew it was true.

Behind us, a man was pushing his way out of the store. The sheriff walked toward us and waved his pistol. We opened up some space and let the man through. I saw the big coil of rope slung over his shoulder. I wanted to cry, but I held it back. He ran along the edge of the street and a couple other men stepped down to join him. Some of them were farmers I recognized from when we delivered our cotton. They looked like ordinary farmers with overalls and farm work boots. But that day, their hateful faces made them different.

As they caught up alongside Pete, the mob seemed to get inspired. Pete had been twisting and screaming all get out, but those men seemed to double their strength when they seen the lynching rope coming. Up by the post office, the old oak tree, the Confederate Tree, they called it, was going to be a gallows.

As the rope got closer to the tree, more men arrived to help. One of them tried to throw it over a big limb, but it fell short. It kept falling short. Some in the crowd jeered as if it were a contest at the county fair. Finally a man tied one end around a horseshoe. It sailed over the big limb, causing a small cloud of dust when it landed. Some cheers and laughter followed as if the spectators was at a picnic.

I looked down at the boardwalk. I saw the gouges and grooves worn over time. I focused on one rough spot that almost had the shape of a half-moon. I would of studied it forever, but I couldn't help but look up. It had seemed as if we were all in slow motion and now everything was happening so fast. Someone had pulled a wagon into the shade under the rope. The horse was whinnying and nervous. A couple men were up front giving it some kindness and making it calm.

Pete was closer now, could see the rope and the wagon. His shouts and protests had changed to cries for mercy.

"I swear to God it wasn't me. Have mercy, you've got the wrong man. I didn't touch her."

Pete's eyes had a wild look as more men began milling around him. He was up on his feet now, but it was more that they was holding him up. Pete was swaying, as if he was about to faint. His face was all bloodied, but his eyes could see clear what was going to happen.

His arms were pinned behind him and someone had bound him around the wrists. One of the men in the buckboard said, "Get that boy up here."

As they reached to grab his legs Pete started to kick wildly. His boot kicked one of them under the chin. A farmer, actually a moon shiner, by the name of Norris staggered and went down as blood spurted out of his mouth and onto his overalls.

"Damn."

Spitting out a tooth and a mouthful of blood, he said "That nigger hurt me!"

Some men went over to help him but Norris waved them off and regained his feet. It had gotten awfully still and you could hear his boots scrape across the hard dirt as he pulled himself up. He walked, kinda punch drunk from the kick to the head, till he was maybe two feet from Pete. He was swaying a bit and trembling from his anger. Now it was Pete that stood steady and still.

Some men were still holding Pete tight from behind so that he couldn't even budge. But if Pete knew he was gonna die, the fear had left his face. Though Pete was just a boy, he must of been four to five inches taller than Norris. He just looked down at Norris, looked him in the eye. Most always we was supposed to look down at the ground when a white man was talking, and this seemed to set Norris off even more.

Norris was a squat man but he was powerful and broad across the shoulders. The first punch was so hard to the stomach that across the square we could hear the air push out of Pete's chest. Even the two men who held Pete was pushed back a step by that blow. They seemed to brace their legs for the next blow, and Pete sagged. I didn't want to look, but I seen it all.

The gunshot took me by surprise. I saw the smoke drifting out of the crowd and followed that to see where it came from. The sheriff didn't say nothing, he just walked slowly toward Norris and holstered his gun. My heart lifted. It was like the reverend told us: All had been darkness and now there was light.

I watched Norris and saw that all the bluster was gone. I turned and looked up at my father. His lips were set, but there was a questioning look in his eyes. Mostly, I looked at Pete. He wasn't smiling, but I could see there was hope in his eyes as they followed the sheriff.

It seemed like forever came and went till he stopped in front of Norris.

It was like a low whisper, but the sheriff's voice carried across the crowd.

"This ain't your show, Norris."

People talk about white trash around here. My mama and papa won't let us call anyone white trash, but it seemed that's what the sheriff was saying to Norris, the way that he talked to him like he was a dog that better get himself off the porch. While lots of white folks would buy moonshine from Norris, you could tell that at the same time everyone thought he was shiftless and no account.

Pete was watching the sheriff, but the sheriff, he didn't even take no notice of him. He nodded to the half-dozen men gathered in front of the buckboard and walked back toward the crowd. It was as if he had given his blessing.

Pete had taken the best that Norris had to offer, but you could see that it was the sheriff that had delivered a crushing blow. Pete's legs buckled. He moaned as those men dragged him the remaining few feet around to the back of the buckboard.

"I didn't do nothing," Pete cried in a voice that rang without hope.

I buried my head against my father's chest.

When I heard the whip snap and the buckboard lurch forward, I looked back. Pete's neck broke instantly; his head rested at an awkward angle. His eyes were open and he looked out at everyone.

As he swayed from the tree, the crowd hushed and tried to look away from his accusing eyes. Not till Pete's body stopped swinging did anyone move. The crowd broke up in silence and went their separate ways.

I didn't want to, but as we left Marshall I turned round in my seat and looked. Pete was still looking at me and I knew that he always would be. Pete would stay till morning. When they did a lynching, they made us leave the body hanging, to put a terror in the colored folk.

His face looked different than I had ever seen it, but Papa still hadn't said a word. First time I looked up from the wagon, I noticed that we were already passing Miller's Swamp. We was halfway home and I hadn't wanted to raise my eyes to the world. I had always looked closely when we passed the swamp, see if I could see any muskrats or water moccasins. Now I didn't care. I would never care again, I promised myself.

I had been thinking hard, though. We lived just three miles from the Johnsons, a white family. And since I was eight, I had been feeding hogs at the McCready and Barker farms. They always paid like they promised, or most often sent home a slab of beef or salt pork in exchange for my work. But after what I saw, I decided that life was different now. I figured I owed that to Pete.

"I will never work for or talk to a white person again," I said with anger.

My father, who had seemed lost in his own thoughts, jerked his head and looked at me.

"That was wrong what they did," I said. "Those white folks are mean and nasty people."

Papa swallowed hard and pulled up on the reins so that the wagon stopped.

He turned toward me. "No. You will work for white folks. You will talk to them."

"But, Papa, what about Pete? He didn't do nothing and they killed him."

"Yeah, I know they had no cause for that, but-"

I cut my father off short, something I had never done.

"But they made Pete suffer so."

"His suffering is over, son. It's all over for Pete. You don't need to worry for him."

"They took his life. Pete was still young. He should of grown to be a man.

"That's so," Papa said. "It was Pete's time, though. His time had come and that's that."

My anger still had some hold on me and I swallowed hard.

Papa looked at me and said, "Some of those white folks was mean and nasty. Some were just scared. It doesn't matter. You have no right to judge another human being. Don't you ever forget."

My father had spoken.

There was nothing to say. I didn't know it then, but his words set the direction my life would take even till this day.

A year earlier, I had been kicked by the mule. It hurt like all get-out. I couldn't work for three days, but I didn't cry. I was proud that I was man enough to take it. But this hurt worse. I cried and my daddy wrapped his arms around me and held me to his chest. Then something broke loose deep inside. I didn't know a body could have so many tears.

I cried for me. I cried for Pete. I cried for the little ones and for Mama and Papa. I cried for all the pain that there was in this world. Papa had his own tears and he just held me.

When the tears slowed, Papa told me, "This morning, I said that you did a man's work. But you was still a boy. Now you are learning to be a man."

After we got home, I found my peppermint was still in my pocket. I scraped off the lint and the dirt. I gave it to one of my little sisters. My taste for it had disappeared. Ninety years later, I still don't like peppermint.

About six months after the lynching, Betty Jo had her baby. It was a boy, a little white boy. No one said nothing. I guess by then most folks, white folks anyway, had all forgotten. I didn't forget. Mama said that maybe where Pete is now, if they have a team, colored could play in those big leagues. I think, Pete would be starting at shortstop.

I'm one hundred and one years old now. But I still remember. Though that was over ninety years ago, I see it in my mind like I was there today. I can't let loose of my memories, even if I wanted to. Yeah, I've seen it all in these hundred years, the good and the bad. My memory works fine. I can tell you everything you want to know.

"Take your time, son," my father said with a grin. "You did a man's work this year."

Putting his hand on my shoulder, he said to the store clerk, "He's all of ten years, but the boy crushed as much cane as I did." Since the age of four, I had always been working to help the family.

I don't know if it was pride from Father's words or the pleasure from a piece of hard candy that beckoned, but I felt so good I thought I would burst. I had been thinking of those hard candies since my father woke me before daybreak and said, "Hitch the wagon. We gonna take some ribbon syrup into town and you comin'."

When I went back inside, the stove was going and Ma had a pot of mush cooling. We ate quiet-like so as not to wake the little ones that were asleep on the other side of the room.

I was happy to see they was still sleeping for it was uncommon to spend the day alone with my father. We never had much time to talk and I just liked to be with him.

Two barrels of cane syrup were tied down in the wagon. We sat up front. My father clucked toward the mule. I wanted to tell him that I was glad he was taking me and it was going to be just him and me together all day. Trouble was, I didn't know how to say that in words. So under the shadow of my straw hat, I just looked over at him.

Solid is what I would say. He took care of us. We had potatoes and carrots buried in the straw and salt pork hangin' from the rafters. We was free of worries. Papa was a good provider. Someday I would be just like him.

Must have been a couple of hours toward town when my father nudged me. He handed me the reins and unwrapped some burlap. I took a piece of cornbread with a big dab of lard on it. When I commenced to eat, he started talking.

"With this ribbon syrup, we be out of debt and have some left for trading. We gonna have seeds for cotton, some new banty chicks, and the fruit trees that are gonna bear fruit next year. No one has the fever and we all be healthy.

"Life is good." And with a grin, he added, "I do believe it's getting better." I liked it when Papa talked to me as a man.

The morning haze had long ago burned off. The wagon stirred up a lot of dust that kind of settled over everything in a nice, smooth blanket. It was good for the mule as the dust had a way of keeping the flies off. Nothing else was said for the next hour, till we came around the last stand of trees and to the rise above Marshall.

In those days, I had in my mind that Marshall was maybe about the biggest and the best place there could ever be. The hardware store had big windows that I liked to look in. I had never been inside since I knew they didn't appreciate black folks with no money. I was partial to the general store, but I liked to walk by the livery stable too. Once a man gave me two bits to rub down and watch his horse for the afternoon. It was 1908, and I hadn't yet seen a car. I had heard of them, but nobody I knew owned one. Papa said that they didn't do too well when the rains came and the roads was deep in mud. Besides, they scared the horses. Mostly, I just liked seeing all the folks from the big ranches and the little farms like ours that was out on the boardwalk.

The cafe and the barbershop was whites only, but I knew a boy that worked in the cafe. And I knew some folks that shined shoes at the barbershop. I liked to look in those windows too.

We never had no cause to go into the post office. But I pictured that one day someone would say there was a letter waiting for me. I would walk past all the folks sitting in the town square beneath the big oak tree. When I was inside, I would say, "I'm George Dawson. I'm here to get my letter." I don't know when that was gonna happen but maybe someday it would. Marshall was a busy place and good things could just happen. It was the county seat and that had to count for something too. At least, that's what I thought then.

But at that moment, in the general store, when my father told me that I could do a man's work, anything seemed possible. I remember everything. I saw the white man frowning, my father grinning at me, and those barrels of candy to choose from. I also remember everything my ears told me that day.

As I picked up a piece of peppermint, I heard a commotion from the street. My father's gaze followed mine. It was dark and cool in the store and the hot light through the doors caused a confusing picture. There were people running, harsh words, and a lot of shouting. Papa set down a kerosene lamp he was inspecting on the counter and run to the door. I followed with the counterman behind me.

At first, out on the boardwalk, in the bright sunlight, I couldn't see the faces on the street. I heard Pete's voice before I saw him.

"It wasn't me. I didn't touch her," Pete screamed. "Lord, let me go."

I would of backed off from what I saw, but by then we was crowded up against the rail. First time in my life I saw the white folks and the colored folks together in a crowd.

It scared me. There was no more frown on the face of the white counterman that was beside of me. His lips were set in a smile. Hate was in his eyes. Across the street, in front of the barbershop, I saw three colored men frozen in place. The white folks surrounding them had red, twisted faces.

They were screaming. I had done nothing, but I felt them screaming at me.

"Kill the nigger boy, kill the nigger. They can't be messing with our white women."

Six men had Pete by the arms. The toes of his boots dragged in the dust. His face looked up to the sky as he screamed, "I didn't touch her."

I knew Pete and knew that was so. I shouted, "Pete, I'll tell-"

My father's hand clamped over my mouth. His other arm crushed the air right out of my chest. I read his eyes and then he slowly let me go without saying a word. I knew it wasn't so, though. The Riley's cook had heard the whole thing; she just kept on working in the kitchen and watched Betty Jo and her father. She was right there, but they didn't even notice she was alive.

She was scared about what they said and I heard her talking to my mama about it. Betty Jo had gotten herself in trouble. Folks already knew that she had a thing for one of the Jackson boys and was spending a lot of time with him. When her daddy found out she was with a child, she had a whipping coming sure enough. Her daddy was steaming mad and of short temper anyhow.

"Who's the boy that done this to you?" her daddy shouted. Sally looked at the belt in his hand. She was crying but wouldn't say nothing. She was scared, and afraid to tell the boy's name, because she figured that her daddy just might go off and kill him.

"Well, if you did this 'cause you wanted to, a good beating will teach you right."

She cried even harder then.

"Well, you got it coming unless maybe this happened against your will."

Her crying slowed and seeing a way out of a beating she listened close.

"Is that what happened?" he said slowly.

Scared as she was, Betty Jo could tell that the safe answer was yes. Not wanting to tell a whole lie, she just nodded her head.

"Damn. Was it that Jackson boy from across the ridge?"

Betty Jo, she loved him, or at least thought she did, shook her head no.

Her daddy looked at her hard. His face turned angry and he said, "Was it our hired boy, Pete? That worthless, lazy nigger! Did he rape you? Did he do this?"

To each question, she just nodded in the smallest way. The tears still flowed, but he threw the belt down and stormed out the door.

"There is one nigger gonna pay for this."

Pete was seventeen and the hired boy around their farm; picking cotton, cutting cane, chores like that. He was a good worker. But he was smart and he knew enough not to even look at a white woman.

I knew Pete since we were little. He was older than me, but he treated me well. Pete was the one who swum out and saved Jimmy Blake at the swimming hole. Jimmy had smacked his head on the corner of the raft when he was showing off for us little kids. Everyone was afraid to swim out that far, but he done it. Pete, he would do anything for anybody.

As I was growing up, I didn't have any toys, but I did still own a baseball that Pete had given me a year earlier. We had been at the pasture of a Sunday afternoon last summer. I had helped to cut the field. A team from Tyler had come over to play some of our boys from Marshall. We didn't have a real stadium, but we would go out and mow the pasture, and set up table for a big Sunday feast and get together afterward. Pete played shortstop. He was good too. If you wanted fast, you should have seen Pete run the bases.

The score was tied and went to extra innings. In the eleventh Pete came up with a man on first, two outs. He took their pitcher full count. And then ... and then he almost hit a cow. It would of been a home run if we had fences. As it was, he got a triple and drove in the winning run. I cheered and cheered for our Marshall boys, especially for Pete.

I was proud of him when the team gave him the game ball. He gave me that ball and said, "You practice with it, George. You'll be a hitter someday too." I was awful pleased but I could barely mutter thank you when my mama nudged me. Pete was my hero.

The colored couldn't play in the big leagues, but if they could I know Pete would of made it.

Yeah, someone had committed a sin and Pete was gonna pay for it. I looked down the boardwalk. They was dragging Pete in the direction of the post office. Sheriff Tate stepped off the boardwalk up ahead from where the mob was. I let out a big breath of air. The sheriff was a big man. I had heard it said that, on a bet, he had carried a barrel of molasses on his back from the general store down past the saloon. They say that once when things got out of hand at the rodeo and the crowd threatened an official, the sheriff took care of it himself. He laid six men out cold before the crowd settled down. I knew he could stop this. People was spilling off the boardwalk and cursing Pete something terrible.

"We gonna keep our women safe."

"Make that boy pay and show all the niggers that they can't get away with this."

Pete was kicking and thrashing, but the mob was still hauling him farther down the street. Taking a few steps along the edge of the road, the sheriff stopped. He kicked the dust and planted his feet. He had big, shiny-looking boots that dust didn't want to stick to. His pants, tucked into the boots, had a stripe down the sides. A big pistol hung off his belt. He pulled the pistol out and crossed his arms so that the pistol set against his chest.

He turned and looked back toward the boardwalk. The sheriff was in front of a group of colored that was pressed into the crowd. He scowled and sent them a message that gave me a chill on a hot day. I had heard tell that the sheriff ran with the Klan at night when they would come through the colored section or out to the colored farms. They would leave a burning cross or shoot some windows out. That's what people said about him and now I knew it was true.

Behind us, a man was pushing his way out of the store. The sheriff walked toward us and waved his pistol. We opened up some space and let the man through. I saw the big coil of rope slung over his shoulder. I wanted to cry, but I held it back. He ran along the edge of the street and a couple other men stepped down to join him. Some of them were farmers I recognized from when we delivered our cotton. They looked like ordinary farmers with overalls and farm work boots. But that day, their hateful faces made them different.

As they caught up alongside Pete, the mob seemed to get inspired. Pete had been twisting and screaming all get out, but those men seemed to double their strength when they seen the lynching rope coming. Up by the post office, the old oak tree, the Confederate Tree, they called it, was going to be a gallows.

As the rope got closer to the tree, more men arrived to help. One of them tried to throw it over a big limb, but it fell short. It kept falling short. Some in the crowd jeered as if it were a contest at the county fair. Finally a man tied one end around a horseshoe. It sailed over the big limb, causing a small cloud of dust when it landed. Some cheers and laughter followed as if the spectators was at a picnic.

I looked down at the boardwalk. I saw the gouges and grooves worn over time. I focused on one rough spot that almost had the shape of a half-moon. I would of studied it forever, but I couldn't help but look up. It had seemed as if we were all in slow motion and now everything was happening so fast. Someone had pulled a wagon into the shade under the rope. The horse was whinnying and nervous. A couple men were up front giving it some kindness and making it calm.

Pete was closer now, could see the rope and the wagon. His shouts and protests had changed to cries for mercy.

"I swear to God it wasn't me. Have mercy, you've got the wrong man. I didn't touch her."

Pete's eyes had a wild look as more men began milling around him. He was up on his feet now, but it was more that they was holding him up. Pete was swaying, as if he was about to faint. His face was all bloodied, but his eyes could see clear what was going to happen.

His arms were pinned behind him and someone had bound him around the wrists. One of the men in the buckboard said, "Get that boy up here."

As they reached to grab his legs Pete started to kick wildly. His boot kicked one of them under the chin. A farmer, actually a moon shiner, by the name of Norris staggered and went down as blood spurted out of his mouth and onto his overalls.

"Damn."

Spitting out a tooth and a mouthful of blood, he said "That nigger hurt me!"

Some men went over to help him but Norris waved them off and regained his feet. It had gotten awfully still and you could hear his boots scrape across the hard dirt as he pulled himself up. He walked, kinda punch drunk from the kick to the head, till he was maybe two feet from Pete. He was swaying a bit and trembling from his anger. Now it was Pete that stood steady and still.

Some men were still holding Pete tight from behind so that he couldn't even budge. But if Pete knew he was gonna die, the fear had left his face. Though Pete was just a boy, he must of been four to five inches taller than Norris. He just looked down at Norris, looked him in the eye. Most always we was supposed to look down at the ground when a white man was talking, and this seemed to set Norris off even more.

Norris was a squat man but he was powerful and broad across the shoulders. The first punch was so hard to the stomach that across the square we could hear the air push out of Pete's chest. Even the two men who held Pete was pushed back a step by that blow. They seemed to brace their legs for the next blow, and Pete sagged. I didn't want to look, but I seen it all.

The gunshot took me by surprise. I saw the smoke drifting out of the crowd and followed that to see where it came from. The sheriff didn't say nothing, he just walked slowly toward Norris and holstered his gun. My heart lifted. It was like the reverend told us: All had been darkness and now there was light.

I watched Norris and saw that all the bluster was gone. I turned and looked up at my father. His lips were set, but there was a questioning look in his eyes. Mostly, I looked at Pete. He wasn't smiling, but I could see there was hope in his eyes as they followed the sheriff.

It seemed like forever came and went till he stopped in front of Norris.

It was like a low whisper, but the sheriff's voice carried across the crowd.

"This ain't your show, Norris."

People talk about white trash around here. My mama and papa won't let us call anyone white trash, but it seemed that's what the sheriff was saying to Norris, the way that he talked to him like he was a dog that better get himself off the porch. While lots of white folks would buy moonshine from Norris, you could tell that at the same time everyone thought he was shiftless and no account.

Pete was watching the sheriff, but the sheriff, he didn't even take no notice of him. He nodded to the half-dozen men gathered in front of the buckboard and walked back toward the crowd. It was as if he had given his blessing.

Pete had taken the best that Norris had to offer, but you could see that it was the sheriff that had delivered a crushing blow. Pete's legs buckled. He moaned as those men dragged him the remaining few feet around to the back of the buckboard.

"I didn't do nothing," Pete cried in a voice that rang without hope.

I buried my head against my father's chest.

When I heard the whip snap and the buckboard lurch forward, I looked back. Pete's neck broke instantly; his head rested at an awkward angle. His eyes were open and he looked out at everyone.

As he swayed from the tree, the crowd hushed and tried to look away from his accusing eyes. Not till Pete's body stopped swinging did anyone move. The crowd broke up in silence and went their separate ways.

I didn't want to, but as we left Marshall I turned round in my seat and looked. Pete was still looking at me and I knew that he always would be. Pete would stay till morning. When they did a lynching, they made us leave the body hanging, to put a terror in the colored folk.

His face looked different than I had ever seen it, but Papa still hadn't said a word. First time I looked up from the wagon, I noticed that we were already passing Miller's Swamp. We was halfway home and I hadn't wanted to raise my eyes to the world. I had always looked closely when we passed the swamp, see if I could see any muskrats or water moccasins. Now I didn't care. I would never care again, I promised myself.

I had been thinking hard, though. We lived just three miles from the Johnsons, a white family. And since I was eight, I had been feeding hogs at the McCready and Barker farms. They always paid like they promised, or most often sent home a slab of beef or salt pork in exchange for my work. But after what I saw, I decided that life was different now. I figured I owed that to Pete.

"I will never work for or talk to a white person again," I said with anger.

My father, who had seemed lost in his own thoughts, jerked his head and looked at me.

"That was wrong what they did," I said. "Those white folks are mean and nasty people."

Papa swallowed hard and pulled up on the reins so that the wagon stopped.

He turned toward me. "No. You will work for white folks. You will talk to them."

"But, Papa, what about Pete? He didn't do nothing and they killed him."

"Yeah, I know they had no cause for that, but-"

I cut my father off short, something I had never done.

"But they made Pete suffer so."

"His suffering is over, son. It's all over for Pete. You don't need to worry for him."

"They took his life. Pete was still young. He should of grown to be a man.

"That's so," Papa said. "It was Pete's time, though. His time had come and that's that."

My anger still had some hold on me and I swallowed hard.

Papa looked at me and said, "Some of those white folks was mean and nasty. Some were just scared. It doesn't matter. You have no right to judge another human being. Don't you ever forget."

My father had spoken.

There was nothing to say. I didn't know it then, but his words set the direction my life would take even till this day.

A year earlier, I had been kicked by the mule. It hurt like all get-out. I couldn't work for three days, but I didn't cry. I was proud that I was man enough to take it. But this hurt worse. I cried and my daddy wrapped his arms around me and held me to his chest. Then something broke loose deep inside. I didn't know a body could have so many tears.

I cried for me. I cried for Pete. I cried for the little ones and for Mama and Papa. I cried for all the pain that there was in this world. Papa had his own tears and he just held me.

When the tears slowed, Papa told me, "This morning, I said that you did a man's work. But you was still a boy. Now you are learning to be a man."

After we got home, I found my peppermint was still in my pocket. I scraped off the lint and the dirt. I gave it to one of my little sisters. My taste for it had disappeared. Ninety years later, I still don't like peppermint.

About six months after the lynching, Betty Jo had her baby. It was a boy, a little white boy. No one said nothing. I guess by then most folks, white folks anyway, had all forgotten. I didn't forget. Mama said that maybe where Pete is now, if they have a team, colored could play in those big leagues. I think, Pete would be starting at shortstop.

I'm one hundred and one years old now. But I still remember. Though that was over ninety years ago, I see it in my mind like I was there today. I can't let loose of my memories, even if I wanted to. Yeah, I've seen it all in these hundred years, the good and the bad. My memory works fine. I can tell you everything you want to know.

Recenzii

“A remarkable autobiography . . . . the feel-good story of the year.”—The Christian Science Monitor

“A testament to the power of perseverance.”—USA Today

“Life Is So Good is about character, soul and spirit. . . . The pride in standing his ground is matched—maybe even exceeded—by the accomplishment of [George Dawson’s] hard-won education.”—The Washington Post

“Eloquent . . . engrossing . . . an astonishing and unforgettable memoir.”—Publishers Weekly

“A testament to the power of perseverance.”—USA Today

“Life Is So Good is about character, soul and spirit. . . . The pride in standing his ground is matched—maybe even exceeded—by the accomplishment of [George Dawson’s] hard-won education.”—The Washington Post

“Eloquent . . . engrossing . . . an astonishing and unforgettable memoir.”—Publishers Weekly