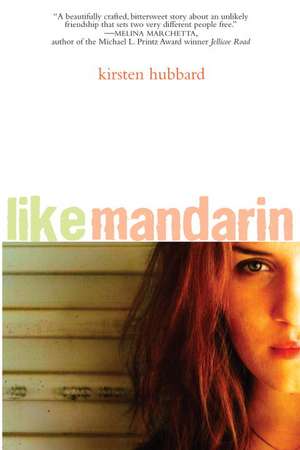

Like Mandarin

Autor Kirsten Hubbarden Limba Engleză Paperback – 29 feb 2012 – vârsta de la 14 ani

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

San Diego Book Awards (2012)

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 63.70 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 96

Preț estimativ în valută:

12.19€ • 12.68$ • 10.22£

12.19€ • 12.68$ • 10.22£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780385739368

ISBN-10: 0385739362

Pagini: 308

Dimensiuni: 137 x 203 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Editura: Ember

ISBN-10: 0385739362

Pagini: 308

Dimensiuni: 137 x 203 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Editura: Ember

Notă biografică

As a travel writer and young adult author, KIRSTEN HUBBARD has hiked ancient ruins in Cambodia, dived with wild dolphins in Belize (one totally looked her in the eye), and navigated the Wyoming Badlands (without a compass) in search of transcendent backdrops. She lives with her husband and their dog. This is her first novel.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

1

Only Weep When You Win

My little sister, Taffeta, peered through a kaleidoscope as we walked to school, her face tipped back, her exposed eye squinched shut. She'd found it in the alley behind Arapahoe Court. Since she refused to give me her hand to hold, I led her by the mitten clipped to the sleeve of her red plaid jacket.

"Stop pulling, Grace," she complained. "My mitten's gonna get yanked off."

"Then pay attention to where you're going."

With her eye still pressed to the battered tube, Taffeta shook her head. She looked like a cat with its head stuck in a Pringles can.

"Fine," I said, releasing her mitten. "If you slip in a patch of slush and crack open your head, don't come bawling to me, all right?"

There wasn't any slush left, though. A few weeks earlier it had clogged the gutters like congealed fat, but by now the last of it had melted.

No matter the season, Taffeta always dragged her feet during our morning walk. She hated school with a passion I never could understand. Her kindergarten classmates adored her, just like the judges of every beauty pageant she entered. She had immense brown eyes and hair the color of baby-duck feathers. A legendary music in her voice. People approached us on Main Street all the time just to hear her speak--which my mother loved.

"Everybody just wishes they had a gift like hers," Momma often said.

As a child, I'd resembled Taffeta, even though we were just half sisters. But whatever in me had appealed to pageant judges had long since vanished. My childhood softness had become a skinny awkwardness, as if my fourteen-year-old self had been nailed together from colt legs and collarbones. My hair was the yellowy tan of oak furniture. I french-braided it every morning to ward off the wind, but pieces always broke free and whipped my face like Medusa coils.

"Taffeta?" I called, realizing she was no longer beside me.

I found her crouched beside a fire ant pile, using her kaleidoscope to poke at the few creatures braving the early-spring air. Twin splotches of mud soiled the knees of her white tights. I sighed, knowing that Momma would find a way to blame the mess on me.

"Taffeta, get up," I ordered.

"Don't call me Taffeta. Call me Taffy and I'll come."

"Taffy's awful," I said, although I didn't think much of Taffeta, either.

"You're awful."

"If you don't get up, I'll freak out."

"You won't."

I started toward her. But my boot skidded in a slick spot, and I had to grab the chain-link fence so I wouldn't fall. I glanced around wildly and decided nobody saw.

"I need to tie my shoe," Taffeta said.

She refused to let me tie them for her, so I crossed my arms and waited. I could already see the school building all the kids in Washokey shared: a faded brick rectangle from the olden days, set against a panorama of dry hills and open range. Endless space. A dead planet.

The badlands.

I'd wandered through the Washokey Badlands Basin so many times I'd memorized the feeling. The forlorn boom of wind. A sky big enough to scare an atheist into prayer. No wonder cowboys sang about being lonesome. Yet somehow, I felt part of something significant out there, collecting mountains whittled into stones to carry with me, like pocket amulets.

I dug in my tote bag until I found that day's stone: a hunk of white quartz the size of a Ping-Pong ball. It wasn't anything special, but I liked the feel of it. Rounded on one side, rough on the other, small enough for me to close my fist around it.

"Done," Taffeta announced.

I grabbed her wrist, ignoring her protests as I towed her schoolward.

Like always, we paused at the edge of the great lawn, still glittering from that morning's watering. But my stomach knotted up even more than usual. The winners of the All-American Essay Contest would be announced in homeroom.

"Can't I go with you today?" Taffeta asked. "I'll be good, Grace, I promise. I hate school. Todd at my table looks up my dress."

"You know you can't come with me. Just keep your legs crossed like Momma told you."

Taffeta scowled at me. "School is horseshit."

My jaw dropped. Before I could demand where she'd heard that word, Taffeta scampered off toward the other kindergartners, brandishing her kaleidoscope. They swarmed around her like ants to a fallen bit of candy.

I remained awhile longer, squeezing my quartz stone and watching the high school students on the other side of the lawn. At the beginning of the year, administration had decided I belonged with the sophomores, a year ahead of my class, instead of with the kids my age. Like I could possibly fit in any less.

It was as if all the other students spoke some language no one had ever taught me. The pretty girls, who squealed with laughter. The monkey-armed guys in cowboy hats, who never looked my way. The wholesome farm kids, like glasses of milk, and the bored bad kids, who made their own fun. I didn't even fit in with the so-called brainy kids--the handful of them--because either they knew how to fake it, to stand out in a good way, or they were weird. Like Davey Miller, who thought wearing socks with sandals was the greatest idea since Velcro.

The bell rang, and the other kids headed for the double doors. I knew that Mandarin Ramey probably wasn't among them, but I searched for her anyway.

From the Hardcover edition.

Only Weep When You Win

My little sister, Taffeta, peered through a kaleidoscope as we walked to school, her face tipped back, her exposed eye squinched shut. She'd found it in the alley behind Arapahoe Court. Since she refused to give me her hand to hold, I led her by the mitten clipped to the sleeve of her red plaid jacket.

"Stop pulling, Grace," she complained. "My mitten's gonna get yanked off."

"Then pay attention to where you're going."

With her eye still pressed to the battered tube, Taffeta shook her head. She looked like a cat with its head stuck in a Pringles can.

"Fine," I said, releasing her mitten. "If you slip in a patch of slush and crack open your head, don't come bawling to me, all right?"

There wasn't any slush left, though. A few weeks earlier it had clogged the gutters like congealed fat, but by now the last of it had melted.

No matter the season, Taffeta always dragged her feet during our morning walk. She hated school with a passion I never could understand. Her kindergarten classmates adored her, just like the judges of every beauty pageant she entered. She had immense brown eyes and hair the color of baby-duck feathers. A legendary music in her voice. People approached us on Main Street all the time just to hear her speak--which my mother loved.

"Everybody just wishes they had a gift like hers," Momma often said.

As a child, I'd resembled Taffeta, even though we were just half sisters. But whatever in me had appealed to pageant judges had long since vanished. My childhood softness had become a skinny awkwardness, as if my fourteen-year-old self had been nailed together from colt legs and collarbones. My hair was the yellowy tan of oak furniture. I french-braided it every morning to ward off the wind, but pieces always broke free and whipped my face like Medusa coils.

"Taffeta?" I called, realizing she was no longer beside me.

I found her crouched beside a fire ant pile, using her kaleidoscope to poke at the few creatures braving the early-spring air. Twin splotches of mud soiled the knees of her white tights. I sighed, knowing that Momma would find a way to blame the mess on me.

"Taffeta, get up," I ordered.

"Don't call me Taffeta. Call me Taffy and I'll come."

"Taffy's awful," I said, although I didn't think much of Taffeta, either.

"You're awful."

"If you don't get up, I'll freak out."

"You won't."

I started toward her. But my boot skidded in a slick spot, and I had to grab the chain-link fence so I wouldn't fall. I glanced around wildly and decided nobody saw.

"I need to tie my shoe," Taffeta said.

She refused to let me tie them for her, so I crossed my arms and waited. I could already see the school building all the kids in Washokey shared: a faded brick rectangle from the olden days, set against a panorama of dry hills and open range. Endless space. A dead planet.

The badlands.

I'd wandered through the Washokey Badlands Basin so many times I'd memorized the feeling. The forlorn boom of wind. A sky big enough to scare an atheist into prayer. No wonder cowboys sang about being lonesome. Yet somehow, I felt part of something significant out there, collecting mountains whittled into stones to carry with me, like pocket amulets.

I dug in my tote bag until I found that day's stone: a hunk of white quartz the size of a Ping-Pong ball. It wasn't anything special, but I liked the feel of it. Rounded on one side, rough on the other, small enough for me to close my fist around it.

"Done," Taffeta announced.

I grabbed her wrist, ignoring her protests as I towed her schoolward.

Like always, we paused at the edge of the great lawn, still glittering from that morning's watering. But my stomach knotted up even more than usual. The winners of the All-American Essay Contest would be announced in homeroom.

"Can't I go with you today?" Taffeta asked. "I'll be good, Grace, I promise. I hate school. Todd at my table looks up my dress."

"You know you can't come with me. Just keep your legs crossed like Momma told you."

Taffeta scowled at me. "School is horseshit."

My jaw dropped. Before I could demand where she'd heard that word, Taffeta scampered off toward the other kindergartners, brandishing her kaleidoscope. They swarmed around her like ants to a fallen bit of candy.

I remained awhile longer, squeezing my quartz stone and watching the high school students on the other side of the lawn. At the beginning of the year, administration had decided I belonged with the sophomores, a year ahead of my class, instead of with the kids my age. Like I could possibly fit in any less.

It was as if all the other students spoke some language no one had ever taught me. The pretty girls, who squealed with laughter. The monkey-armed guys in cowboy hats, who never looked my way. The wholesome farm kids, like glasses of milk, and the bored bad kids, who made their own fun. I didn't even fit in with the so-called brainy kids--the handful of them--because either they knew how to fake it, to stand out in a good way, or they were weird. Like Davey Miller, who thought wearing socks with sandals was the greatest idea since Velcro.

The bell rang, and the other kids headed for the double doors. I knew that Mandarin Ramey probably wasn't among them, but I searched for her anyway.

From the Hardcover edition.

Premii

- San Diego Book Awards Winner, 2012