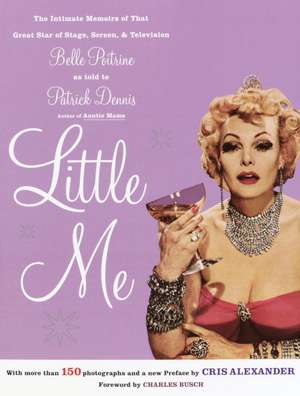

Little Me

Autor Patrick Dennisen Limba Engleză Paperback – 15 oct 2002

For Belle Poitrine, née Mayble Schlumpfert, all the world's a stage and she's the most important player on it. At once coy and coercive, with a name that means "beautiful bosom" in French, she claws her way from Striver's Row to the silver screen. Recalling Belle's career, which ranged from portraying Anne Boleyn in Oh, Henry to roles in both Sodom and its sequel Gomorrah (not to mention the classic Papaya Paradise), Little Me serves up copious quanitites of husbands, couture, and Pink Lady cocktails, with international adventures and a murder trial to boot.

A runaway bestseller that made its way to Broadway, starring Sid Caesar in 1962 and Martin Short in 1998, Little Me is now reprinted--with all of the 150 historic, hysterical photographs depicting the funniest scenes from Belle's sordid life, including cameo appearances by the author and Rosalind Russell. Considered a collector's item, the first edition of Little Me was like a performance in book form. Now this glittering spoof of celebrity is gloriously reincarnated for connoisseurs of all things chick and cheeky.

Preț: 125.24 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 188

Preț estimativ în valută:

23.98€ • 25.02$ • 20.10£

23.98€ • 25.02$ • 20.10£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 19 februarie-05 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780767913478

ISBN-10: 0767913477

Pagini: 306

Ilustrații: illustrations

Dimensiuni: 178 x 232 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.53 kg

Editura: Crown

ISBN-10: 0767913477

Pagini: 306

Ilustrații: illustrations

Dimensiuni: 178 x 232 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.53 kg

Editura: Crown

Notă biografică

PATRICK DENNIS, the author of Auntie Mame, was the pen name of Edward Everett Tanner III, (1921-1976). One of the most eccentric, celebrated, and widely read writers of the 1950's and '60's, Tanner wrote sixteen novels, a majority of which were national bestsellers.

Extras

chapter one -- A STAR IS BORN

1900-1914

Early days in Venezuela, Illinois * The father I never knew * Momma's genealogy * Momma's business career * School days * Momma's friend, the Professor, introduces me to music * My flair for the arts * The nickelodeon * My patron * Lessons in dramatical attitudes

The sun was just smiling its first shy gleam over the Illinois River when I made my debut into the world--a red, wrinkled, writhing baby girl.

"What day is it?" Momma murmured.

"Why, it's May Day, Miss Schlumpfert," the midwife said. "The first of May."

"Then we'll call her Maybelle," Momma said and drifted off to sleep.

I was a rosy, happy, healthy little thing with bobbing curls and an insatiable curiosity. Everyone who saw me toddling along the dusty streets of Venezuela, Illinois (population--then--9,000) stopped to admire me and it was evident to even the most obtuse that I was going to be a great beauty. But beauty wasn't enough in a hidebound little provincial backwash like Venezuela. "Family" mattered a great deal in the town and, alas, of family I had only dear Momma. I never knew my father. When I was old enough to ask about him, Momma would become very vague and, looking off in the distance, she would answer simply, "He was a traveling man, Belle." Perhaps it was from him that I inherited my lifelong wanderlust.

And, oh! how I longed to wander away from narrow-minded little Venezuela, never to return again. Or--even better--to return as a rich and famous woman, to buy the biggest, finest house on "The Bluff," overlooking the river, and to snub the haute bourgeoisie of Venezuela just as they had once snubbed little Belle Schlumpfert. For tiny Venezuela was divided into three classes. First there were the rich old families who lived in big, beautiful houses with stained-glass windows, portes cochtres, turrets and towers and ornamental iron statues up on "The Bluff." They were the rulers of the town--the Hobans, the Kerrs, the Hollisters, the Williamses with their seven talented daughters. They were the families with "hired girls" and their own buggies, the cream of Venezuela who thought nothing of going to Peoria, or even to Chicago, to do their shopping! Mary Elizabeth Hoban had even visited New York and travelled to Staten Island! Little Belle Schlumpfert was beneath their haughty gaze!

In the lower town were the businessmen and shopkeepers--the clannish middle classes of the community who formed the second stratum of society. They noticed me, all right, but always with contempt. For I lived beyond the Rock Island tracks in Drifters' Row and, even worse, Momma was a career woman--something unheard of in those days.

Drifters' Row was the "shanty town" of Venezuela, peopled by railway men, by the foreign element, by the poor, by those whom life had treated more harshly than the denizens of "The Bluff." Those who lived there had not been in Venezuela for long and presumably did not intend to stay. Hence the name. All of us were looked down upon by the older families of Venezuela. We were the "dregs."

I resented this. I wanted to say "My family is as good as yours--even better. Come and see how we live! Although our house is humble from without, the interior is a thing of beauty." And it was. Momma had exquisite taste and a natural knack for making any place homey, attractive and inviting. In fact, it is from her side of the family that I inherit my own taste--often remarked upon--and my artistic flair. Although our tiny little house had but two small rooms, Momma had made the most of them. She had turned the sitting room into a veritable conversation piece by bringing together her large collection of seashells, the gay Kewpie dolls and souvenirs from her many travels. Almost every inch of wall space was hung with artistic reproductions, pictures of her lovely southern friends and of the distinguished-looking gentlemen she had received. On the center table stood a huge bouquet of bead flowers which Momma had fashioned herself during slow periods at her place of business. A lovely bead and bamboo curtain separated this room from Momma's bedroom. A lamp with a big red silk shade in the front window cast its rosy glow over the entire room.

Nor would Momma ever allow herself to be seen in house dress and apron like the other women of Venezuela. True, in the mornings Momma lolled about in the Morris chair in deshabille--a Japanese kimono, a pink velveteen wrapper trimmed with maribou or her lovely mauve satin with bead fringe (another product of Momma's busy needle). But every day at noon Momma put on one of her beautiful evening gowns and went off to pursue her career as breadwinner for herself and little me. "It's a tradition in our family, Belle," she used to say proudly.

True, Momma was a newcomer to Venezuela, but she had come from something far finer. Momma was a southern aristocrat whose family had been ruined by the Civil War and the depredations of the "carpetbaggers." She never liked to talk much about the past. She told me only that she had come to Venezuela from the finest house in New Orleans. When I asked her why, she said simply, "New Orleans was unhealthy for me. Now run along." Although Momma always seemed a pillar of strength to me, I guess she was just a delicate southern flower underneath.

Although it was on Drifters' Row, Momma's place of employment was one of the most beautiful establishments in Venezuela. Momma had accepted a position with Madam Louise, another New Orleans belle, who had opened a sort of gentlemen's hotel and social club near the depot. Madam Louise catered mostly to lonely travelling salesmen who needed cheering up in a strange town, and even a few gentlemen from the families on "The Bluff" would drop in for a glass of wine, a bit of music and some stimulating conversation after their tasks of the day were done. Evenings, Saturday afternoons and Sundays were especially busy. In order to keep her thriving establishment going, Madam Louise employed Momma and three or four of the better conversationalists among the ladies of Drifters' Row. Although Madam Louise did not often permit me to enter her place of business, the few times I was permitted into the parlor were to little me like visits to a veritable fairy land. It was an intimate room with red damask walls, deep red sofas, potted palms, a statue of Venus and a magnificent gas chandelier with rose shades. On a draped table were plush-bound albums containing photographs of Madam Louise's hostesses, which Momma never permitted me to see. In an alcove there was a "Turkish corner" with a divan covered by a red Oriental rug and many "whatnots" filled with the most amazing collection of curios. Against some exquisite Spanish shawls stood a lovely black and gold upright piano where Madam Louise's distinguished friend the Professor played such grand old songs as "In the Good Old Summertime," "Meet Me in St. Louis, Louis" and "There's No Place Like Home." If it was from Momma and Madam Louise that I first learned about visual beauty, it was from the Professor--that kindly old gentleman strumming the keyboard in Madam Louise's stunning parlor--that I acquired my lifelong appreciation of music.

I am told that the bedrooms upstairs were every bit as tasteful and luxuriously furnished, but I was never privileged to see them.

Because she was French and not of Venezuela, Madam Louise was not "received" by the grandes dames who lived up on "The Bluff," nor by the housewives in the lower town. But you could easily tell that the women of the town felt a great respect for her as she was the only woman in Venezeula to be called Madam.

Of course there was a school in Venezuela and of course I was sent to it. Naturally quick and bright, I paid little attention to what the teachers were saying. True, I had a God-given gift for literature and the arts, but I was prone to daydreams and although little Belle Schlumpfert's body may have been in that musty, drab schoolroom, her heart was not. Because of my attitude, several teachers were prejudiced against me and I was often held back to repeat a grade. But I didn't mind. Madam Louise had once said to me, "Belle, honey" (she always called me "Honey"), "as soon as you've developed, you can come to work here." I didn't quite understand what she meant. Knowing that the ladies who worked for Madam Louise were all brilliant conversationalists, I practiced talking quite a lot at school, which, I am afraid, the teachers did not appreciate. But that made no difference to me. I dreamed only of the day when I would be "developed" enough to leave school forever and work with Momma in Madam Louise's beautiful, beautiful establishment.

In my spare time I was very much the lonely dreamer, disdaining the childish games of my classmates (who, by the time I was twelve, were all much younger than I was) to revel in my make-believe world of fantasy. Much of the time was spent in Momma's gracious little drawing room daydreaming over the well-thumbed pages of mail order catalogues from Sears, Roebuck and Montgomery Ward or surreptitiously trying on Momma's many dazzling evening gowns and posing as a grown-up lady in front of the cheval glass. Although I was only twelve, I noticed that I was different from the other girls in school for already I was becoming endowed with tantalizing curves and swellings which Momma's decollete creations did nothing to conceal. With a bit of cochineal on my lips and cheeks, with my langorous eyes outlined by a burnt match and my face liberally dusted with poudre de riz, I felt that I could pass as a young woman of eighteen or so. And this must have been true, because even in my prim little school dresses visiting "drummers" would give me the "onceover" as I walked along the quiet streets of the town.

But what really opened my eyes was the opening of the Argosy Nickelodeon right in the heart of Venezuela in 1911. There for the first time I witnessed the magic of what was locally known as "shifting pictures." Every time I came into a nickel--and I am afraid that I will have to admit that sometimes I even "raided" Momma's purse--I would run down to the nickelodeon and sit spellbound at such grand films as The Great Train Robbery, The Reception, Uncle Tom's Cabin and other "thrillers" of that ilk. I knew right then and there what Fate had intended me to be--a great dramatic actress. From that moment on I had but one aim in life--to perform, to bring joy and laughter, heartache and tears to the American public. But I knew that some sort of training in the art of the drama would be essential to bring out my natural endowments as an actress, and where, oh where, would I find the necessary money for my training?

Then, as if by magic, it came to me, right in the Argosy Nickelodeon. Sitting there in the darkened auditorium one evening I suddenly felt a hand on my knee. Out of the corner of my eye I caught a glimpse of my neighbor. To my surprise it was none other than kindly old Mr. Caruthers, the leading citizen of Venezuela. Mr. Caruthers owned not only the box factory and the pickle bottling works, but also much Venezuela real estate, including all of Drifters' Row. He was chairman of the board of the local bank and had vast holdings in farmland throughout Marshall, Woodford, La Salle and Putnam counties. Not only the richest man in town, Mr. Caruthers was also the most respectable--a true civic leader. He was a deacon of the church and an outspoken crusader against any form of vice. (He had even gone so far as to hint that Madam Louise's lovely home was a "blot on the escutcheon" of Venezuela!) In fact, he had been so vehement against the very existence of the Argosy Nickelodeon that I was amazed to find him sitting next to me.

In addition to his many good works on behalf of the underprivileged, Mr. Caruthers was widely known for his interest in young people. Only the year before he had been most active in organizing the town's first Boy Scout troop and a group of Campfire Girls (into which, by some oversight, I had not been invited), and on almost any balmy afternoon he could be found at the abandoned quarry watching the young blades of the town disporting themselves in the "ole swimmin' hole." I could sense now that Mr. Caruthers was beginning to take a deep interest in little me. "Perhaps," I thought, "just perhaps . . ."

At the end of the reel a sign was flashed on the screen. "Ladies," it read, "If Annoyed While Here, Please Inform the Management." Screwing up my courage, I turned to my neighbor and said, "Please, Mr. Caruthers, would you read that to me? I'm only eleven." (In point of fact I was thirteen, but I have never had a "head for figures.") I have never seen a gentleman quite so excited. Over a strawberry soda in Guernsey's Ice Cream Emporium, I poured out my little heart to kindly old Mr. Caruthers. I told him of my hopes and dreams, my desire to receive dramatic coaching, and mentioned once or twice how very surprised I had been to find him sitting right next to little me at a place like the Argosy. By the end of the evening we had worked out an arrangement concerning my future that was to bring profit and pleasure to both of us. As Mr. Caruthers found it necessary to journey to nearby Ottawa on business twice each week, it was agreed that I would accompany him to take instruction in elocution and dramatical attitudes from a Miss Neida Anderson who taught there, returning on the late train to Venezuela with Mr. Caruthers.

Thus it was that Mr. Caruthers became a sort of "patron of the arts," and for the next year that affectionate old gentleman and I travelled to and fro on the Rock Island Line. I was on my way to fame and fortune in the theatre!

1900-1914

Early days in Venezuela, Illinois * The father I never knew * Momma's genealogy * Momma's business career * School days * Momma's friend, the Professor, introduces me to music * My flair for the arts * The nickelodeon * My patron * Lessons in dramatical attitudes

The sun was just smiling its first shy gleam over the Illinois River when I made my debut into the world--a red, wrinkled, writhing baby girl.

"What day is it?" Momma murmured.

"Why, it's May Day, Miss Schlumpfert," the midwife said. "The first of May."

"Then we'll call her Maybelle," Momma said and drifted off to sleep.

I was a rosy, happy, healthy little thing with bobbing curls and an insatiable curiosity. Everyone who saw me toddling along the dusty streets of Venezuela, Illinois (population--then--9,000) stopped to admire me and it was evident to even the most obtuse that I was going to be a great beauty. But beauty wasn't enough in a hidebound little provincial backwash like Venezuela. "Family" mattered a great deal in the town and, alas, of family I had only dear Momma. I never knew my father. When I was old enough to ask about him, Momma would become very vague and, looking off in the distance, she would answer simply, "He was a traveling man, Belle." Perhaps it was from him that I inherited my lifelong wanderlust.

And, oh! how I longed to wander away from narrow-minded little Venezuela, never to return again. Or--even better--to return as a rich and famous woman, to buy the biggest, finest house on "The Bluff," overlooking the river, and to snub the haute bourgeoisie of Venezuela just as they had once snubbed little Belle Schlumpfert. For tiny Venezuela was divided into three classes. First there were the rich old families who lived in big, beautiful houses with stained-glass windows, portes cochtres, turrets and towers and ornamental iron statues up on "The Bluff." They were the rulers of the town--the Hobans, the Kerrs, the Hollisters, the Williamses with their seven talented daughters. They were the families with "hired girls" and their own buggies, the cream of Venezuela who thought nothing of going to Peoria, or even to Chicago, to do their shopping! Mary Elizabeth Hoban had even visited New York and travelled to Staten Island! Little Belle Schlumpfert was beneath their haughty gaze!

In the lower town were the businessmen and shopkeepers--the clannish middle classes of the community who formed the second stratum of society. They noticed me, all right, but always with contempt. For I lived beyond the Rock Island tracks in Drifters' Row and, even worse, Momma was a career woman--something unheard of in those days.

Drifters' Row was the "shanty town" of Venezuela, peopled by railway men, by the foreign element, by the poor, by those whom life had treated more harshly than the denizens of "The Bluff." Those who lived there had not been in Venezuela for long and presumably did not intend to stay. Hence the name. All of us were looked down upon by the older families of Venezuela. We were the "dregs."

I resented this. I wanted to say "My family is as good as yours--even better. Come and see how we live! Although our house is humble from without, the interior is a thing of beauty." And it was. Momma had exquisite taste and a natural knack for making any place homey, attractive and inviting. In fact, it is from her side of the family that I inherit my own taste--often remarked upon--and my artistic flair. Although our tiny little house had but two small rooms, Momma had made the most of them. She had turned the sitting room into a veritable conversation piece by bringing together her large collection of seashells, the gay Kewpie dolls and souvenirs from her many travels. Almost every inch of wall space was hung with artistic reproductions, pictures of her lovely southern friends and of the distinguished-looking gentlemen she had received. On the center table stood a huge bouquet of bead flowers which Momma had fashioned herself during slow periods at her place of business. A lovely bead and bamboo curtain separated this room from Momma's bedroom. A lamp with a big red silk shade in the front window cast its rosy glow over the entire room.

Nor would Momma ever allow herself to be seen in house dress and apron like the other women of Venezuela. True, in the mornings Momma lolled about in the Morris chair in deshabille--a Japanese kimono, a pink velveteen wrapper trimmed with maribou or her lovely mauve satin with bead fringe (another product of Momma's busy needle). But every day at noon Momma put on one of her beautiful evening gowns and went off to pursue her career as breadwinner for herself and little me. "It's a tradition in our family, Belle," she used to say proudly.

True, Momma was a newcomer to Venezuela, but she had come from something far finer. Momma was a southern aristocrat whose family had been ruined by the Civil War and the depredations of the "carpetbaggers." She never liked to talk much about the past. She told me only that she had come to Venezuela from the finest house in New Orleans. When I asked her why, she said simply, "New Orleans was unhealthy for me. Now run along." Although Momma always seemed a pillar of strength to me, I guess she was just a delicate southern flower underneath.

Although it was on Drifters' Row, Momma's place of employment was one of the most beautiful establishments in Venezuela. Momma had accepted a position with Madam Louise, another New Orleans belle, who had opened a sort of gentlemen's hotel and social club near the depot. Madam Louise catered mostly to lonely travelling salesmen who needed cheering up in a strange town, and even a few gentlemen from the families on "The Bluff" would drop in for a glass of wine, a bit of music and some stimulating conversation after their tasks of the day were done. Evenings, Saturday afternoons and Sundays were especially busy. In order to keep her thriving establishment going, Madam Louise employed Momma and three or four of the better conversationalists among the ladies of Drifters' Row. Although Madam Louise did not often permit me to enter her place of business, the few times I was permitted into the parlor were to little me like visits to a veritable fairy land. It was an intimate room with red damask walls, deep red sofas, potted palms, a statue of Venus and a magnificent gas chandelier with rose shades. On a draped table were plush-bound albums containing photographs of Madam Louise's hostesses, which Momma never permitted me to see. In an alcove there was a "Turkish corner" with a divan covered by a red Oriental rug and many "whatnots" filled with the most amazing collection of curios. Against some exquisite Spanish shawls stood a lovely black and gold upright piano where Madam Louise's distinguished friend the Professor played such grand old songs as "In the Good Old Summertime," "Meet Me in St. Louis, Louis" and "There's No Place Like Home." If it was from Momma and Madam Louise that I first learned about visual beauty, it was from the Professor--that kindly old gentleman strumming the keyboard in Madam Louise's stunning parlor--that I acquired my lifelong appreciation of music.

I am told that the bedrooms upstairs were every bit as tasteful and luxuriously furnished, but I was never privileged to see them.

Because she was French and not of Venezuela, Madam Louise was not "received" by the grandes dames who lived up on "The Bluff," nor by the housewives in the lower town. But you could easily tell that the women of the town felt a great respect for her as she was the only woman in Venezeula to be called Madam.

Of course there was a school in Venezuela and of course I was sent to it. Naturally quick and bright, I paid little attention to what the teachers were saying. True, I had a God-given gift for literature and the arts, but I was prone to daydreams and although little Belle Schlumpfert's body may have been in that musty, drab schoolroom, her heart was not. Because of my attitude, several teachers were prejudiced against me and I was often held back to repeat a grade. But I didn't mind. Madam Louise had once said to me, "Belle, honey" (she always called me "Honey"), "as soon as you've developed, you can come to work here." I didn't quite understand what she meant. Knowing that the ladies who worked for Madam Louise were all brilliant conversationalists, I practiced talking quite a lot at school, which, I am afraid, the teachers did not appreciate. But that made no difference to me. I dreamed only of the day when I would be "developed" enough to leave school forever and work with Momma in Madam Louise's beautiful, beautiful establishment.

In my spare time I was very much the lonely dreamer, disdaining the childish games of my classmates (who, by the time I was twelve, were all much younger than I was) to revel in my make-believe world of fantasy. Much of the time was spent in Momma's gracious little drawing room daydreaming over the well-thumbed pages of mail order catalogues from Sears, Roebuck and Montgomery Ward or surreptitiously trying on Momma's many dazzling evening gowns and posing as a grown-up lady in front of the cheval glass. Although I was only twelve, I noticed that I was different from the other girls in school for already I was becoming endowed with tantalizing curves and swellings which Momma's decollete creations did nothing to conceal. With a bit of cochineal on my lips and cheeks, with my langorous eyes outlined by a burnt match and my face liberally dusted with poudre de riz, I felt that I could pass as a young woman of eighteen or so. And this must have been true, because even in my prim little school dresses visiting "drummers" would give me the "onceover" as I walked along the quiet streets of the town.

But what really opened my eyes was the opening of the Argosy Nickelodeon right in the heart of Venezuela in 1911. There for the first time I witnessed the magic of what was locally known as "shifting pictures." Every time I came into a nickel--and I am afraid that I will have to admit that sometimes I even "raided" Momma's purse--I would run down to the nickelodeon and sit spellbound at such grand films as The Great Train Robbery, The Reception, Uncle Tom's Cabin and other "thrillers" of that ilk. I knew right then and there what Fate had intended me to be--a great dramatic actress. From that moment on I had but one aim in life--to perform, to bring joy and laughter, heartache and tears to the American public. But I knew that some sort of training in the art of the drama would be essential to bring out my natural endowments as an actress, and where, oh where, would I find the necessary money for my training?

Then, as if by magic, it came to me, right in the Argosy Nickelodeon. Sitting there in the darkened auditorium one evening I suddenly felt a hand on my knee. Out of the corner of my eye I caught a glimpse of my neighbor. To my surprise it was none other than kindly old Mr. Caruthers, the leading citizen of Venezuela. Mr. Caruthers owned not only the box factory and the pickle bottling works, but also much Venezuela real estate, including all of Drifters' Row. He was chairman of the board of the local bank and had vast holdings in farmland throughout Marshall, Woodford, La Salle and Putnam counties. Not only the richest man in town, Mr. Caruthers was also the most respectable--a true civic leader. He was a deacon of the church and an outspoken crusader against any form of vice. (He had even gone so far as to hint that Madam Louise's lovely home was a "blot on the escutcheon" of Venezuela!) In fact, he had been so vehement against the very existence of the Argosy Nickelodeon that I was amazed to find him sitting next to me.

In addition to his many good works on behalf of the underprivileged, Mr. Caruthers was widely known for his interest in young people. Only the year before he had been most active in organizing the town's first Boy Scout troop and a group of Campfire Girls (into which, by some oversight, I had not been invited), and on almost any balmy afternoon he could be found at the abandoned quarry watching the young blades of the town disporting themselves in the "ole swimmin' hole." I could sense now that Mr. Caruthers was beginning to take a deep interest in little me. "Perhaps," I thought, "just perhaps . . ."

At the end of the reel a sign was flashed on the screen. "Ladies," it read, "If Annoyed While Here, Please Inform the Management." Screwing up my courage, I turned to my neighbor and said, "Please, Mr. Caruthers, would you read that to me? I'm only eleven." (In point of fact I was thirteen, but I have never had a "head for figures.") I have never seen a gentleman quite so excited. Over a strawberry soda in Guernsey's Ice Cream Emporium, I poured out my little heart to kindly old Mr. Caruthers. I told him of my hopes and dreams, my desire to receive dramatic coaching, and mentioned once or twice how very surprised I had been to find him sitting right next to little me at a place like the Argosy. By the end of the evening we had worked out an arrangement concerning my future that was to bring profit and pleasure to both of us. As Mr. Caruthers found it necessary to journey to nearby Ottawa on business twice each week, it was agreed that I would accompany him to take instruction in elocution and dramatical attitudes from a Miss Neida Anderson who taught there, returning on the late train to Venezuela with Mr. Caruthers.

Thus it was that Mr. Caruthers became a sort of "patron of the arts," and for the next year that affectionate old gentleman and I travelled to and fro on the Rock Island Line. I was on my way to fame and fortune in the theatre!

Recenzii

"Enormously funny...Mr. Dennis's dialogue is hilarious, his pages a riot of magnificent absurdities, sly puns, quips, and other verbal buffoonery."

--The New York Times

"A masterpiece of parody."

--The New Republic

"One of the most outlandish collections of narrative and photographic nonsense ever put between hard covers. Only Patrick Dennis of Auntie Mame could have done it."

--Chicago Tribune

--The New York Times

"A masterpiece of parody."

--The New Republic

"One of the most outlandish collections of narrative and photographic nonsense ever put between hard covers. Only Patrick Dennis of Auntie Mame could have done it."

--Chicago Tribune