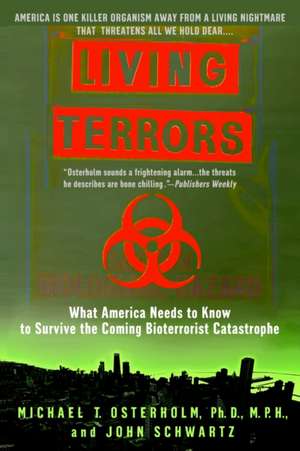

Living Terrors: What America Needs to Know to Survive the Coming Bioterrorist Catastrophe

Autor Michael Osterholm, John Schwartzen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 sep 2001

A deadly cloud of powdered anthrax spores settles unnoticed over a crowded football stadium.... A school cafeteria lunch is infected with a drug-resistant strain of E. coli.... Thousands in a bustling shopping mall inhale a lethal mist of smallpox, turning each individual into a highly infectious agent of suffering and death....

Dr. Michael Osterholm knows all too well the horrifying scenarios he describes. In this eye-opening account, the nation’s leading expert on bioterrorism sounds a wake-up call to the terrifying threat of biological attack — and America’s startling lack of preparedness.

He demonstrates the havoc these silent killers can wreak, exposes the startling ease with which they can be deployed, and asks probing questions about America’s ability to respond to such attacks.

Are most doctors and emergency rooms able to diagnose correctly and treat anthrax, smallpox, and other potential tools in the bioterrorist’s arsenal? Is the government developing the appropriate vaccines and treatments?

The answers are here in riveting detail — what America has and hasn’t done to prevent the coming bioterrorist catastrophe. Impeccably researched, grippingly told, Living Terrors presents the unsettling truth about the magnitude of the threat. And more important, it presents the ultimate insider’s prescription for change: what we must do as a nation to secure our freedom, our future, our lives.

Preț: 72.32 lei

Preț vechi: 87.60 lei

-17% Nou

Puncte Express: 108

Preț estimativ în valută:

13.84€ • 14.40$ • 11.43£

13.84€ • 14.40$ • 11.43£

Disponibilitate incertă

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780385334815

ISBN-10: 0385334818

Pagini: 256

Dimensiuni: 128 x 191 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.19 kg

Editura: DELTA

ISBN-10: 0385334818

Pagini: 256

Dimensiuni: 128 x 191 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.19 kg

Editura: DELTA

Recenzii

“Osterholm sounds a frightening alarm ... the threats he describes are bone chilling, his seven-point plan is sensible and compelling.”

— Publishers Weekly

— Publishers Weekly

Notă biografică

Michael T. Osterholm, Ph.D, M.P.H., the former Minnesota State epidemiologist and former Chair and CEO, ican, INC., has been an internationally recognized leader in the area of infectious diseases for the past two decades. He is the recipient of numerous honors and awards from the CDC, NIH, FDA, and others, and served as a personal advisor to the late King Hussein of Jordan on bioterrorism. He has led numerous successful investigations into infectious disease outbreaks of global importance. A frequent lecturer around the world, he is Director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy and is a professor at the School of Public Health, University of Minnesota.

John Schwartz is a reporter at The New York Times; he covers technology and business.

John Schwartz is a reporter at The New York Times; he covers technology and business.

Extras

Down in the stadium, no one even sees the airplane passing to the north; they are focused on the game below, not the quiet disaster above. The roar of the crowd drowns out the growl of the plane’s engine. By the time the disperse cloud of dust reaches the ground, it’s imperceptible; at two to six microns in size, the spores are smaller than pollen — as many as twenty thousand of them, lined up, would barely stretch an inch. There is nothing to see, and the spores smell of nothing. The spectators, athletes, the billionaire owner in a brief foray out of his skybox — all take the tiny killers deep into their lungs.

Of the 74,000 people attending the game that night, 39,000 are infected. In the surrounding neighborhoods, 150,000 more are infected after inhaling the drifting spores. After the game, the fans go back to their homes. Because it is summer, vacationing families have traveled from all over the country to attend. Over the next day or two, they leave their hotels and return to their homes, scattering across the nation and the world.

The bacterial cells continue to reproduce. After a day or two, many of the victims begin developing a fever and dry cough; some complain of shortness of breath and chest pain. Most of them pop a few Tylenol or Advil and try to ride out the illness. Some see their doctors and are told to take it easy and drink plenty of fluids. Some of the toughest cases show up at emergency rooms. Many patients begin to feel better after a couple of days; only later will they slip back into serious illness.

Within a week of the attack, more than 20,000 people have swamped local hospitals, and the medical establishment and local government are trying to figure out what has happened. The city, even the region, is in utter chaos. Panic has overrun both the government and the medical community. The most susceptible victims rapidly spiral into the agonizing crash of respirator shutdown, with high fever and shortness of breath; many turn blue. Hundreds — only the first hundreds — die. Desperate calls go out for help to the state health department and to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta. There’s little time to discuss the epidemic, however, because the number of cases quickly overtakes the ability of local hospitals to cope.

As the tenth day after the attack dawns, there are 30,000 sick and 700 dead; by the next day those numbers will have jumped to 38,000 sick and 1,500 dead. Doctors’ offices, clinics, and emergency rooms continue to be overwhelmed with people demanding antibiotic treatment. Once the mysterious attack is identified as anthrax, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention begins to send antibiotics from the national pharmaceutical stockpile.

It’s a help, but the world is not perfect; getting the drugs to people turns out to be a logistical nightmare. With assistance from other city and state officials, overwhelmed public health authorities open storefronts to distribute antibiotics, but there aren’t enough warm bodies to help distribute them efficiently. Many of the people who might be expected to help with this operation are too sick with anthrax even to help themselves, let alone others. Lines at the distribution centers stretch around the block, with angry, frightened people pushing and shoving to get the life-saving drugs. Lines give way to mass unorganized crowds; soon they give way to frightened mob scenes. Several distribution centers have to be shut down after fights turn into riots.

Eventually, 20,000 will lose their lives; it is the worst man-made disaster in the history of the world.

This grim scenario and the mind-boggling estimates of death and illness caused by an airborne terrorist attack might seem outrageous — how, after all, could a single act wipe out as many people as are found in whole towns? But it is, in fact, a middle-of-the-road view of the kind of damage that an anthrax attack might cause. Remember that the Office of Technology Assessment estimated that just a couple of hundred pounds of anthrax spores released on a clear, calm night upwind of Washington, D.C., could kill 1 to 3 million people. This scenario is precisely the kind of case study that policy makers and public health officials are now beginning to give careful consideration.

In fact, many of the elements of the preceding scenario were drawn from a 1999 presentation at a bioterrorism conference sponsored by the Johns Hopkins Center for Civilian Biodefense Studies and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. I served on the planning committee for the conference, and we wanted to lay out in black and white what America could expect if an anthrax release occurred.

Of the 74,000 people attending the game that night, 39,000 are infected. In the surrounding neighborhoods, 150,000 more are infected after inhaling the drifting spores. After the game, the fans go back to their homes. Because it is summer, vacationing families have traveled from all over the country to attend. Over the next day or two, they leave their hotels and return to their homes, scattering across the nation and the world.

The bacterial cells continue to reproduce. After a day or two, many of the victims begin developing a fever and dry cough; some complain of shortness of breath and chest pain. Most of them pop a few Tylenol or Advil and try to ride out the illness. Some see their doctors and are told to take it easy and drink plenty of fluids. Some of the toughest cases show up at emergency rooms. Many patients begin to feel better after a couple of days; only later will they slip back into serious illness.

Within a week of the attack, more than 20,000 people have swamped local hospitals, and the medical establishment and local government are trying to figure out what has happened. The city, even the region, is in utter chaos. Panic has overrun both the government and the medical community. The most susceptible victims rapidly spiral into the agonizing crash of respirator shutdown, with high fever and shortness of breath; many turn blue. Hundreds — only the first hundreds — die. Desperate calls go out for help to the state health department and to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta. There’s little time to discuss the epidemic, however, because the number of cases quickly overtakes the ability of local hospitals to cope.

As the tenth day after the attack dawns, there are 30,000 sick and 700 dead; by the next day those numbers will have jumped to 38,000 sick and 1,500 dead. Doctors’ offices, clinics, and emergency rooms continue to be overwhelmed with people demanding antibiotic treatment. Once the mysterious attack is identified as anthrax, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention begins to send antibiotics from the national pharmaceutical stockpile.

It’s a help, but the world is not perfect; getting the drugs to people turns out to be a logistical nightmare. With assistance from other city and state officials, overwhelmed public health authorities open storefronts to distribute antibiotics, but there aren’t enough warm bodies to help distribute them efficiently. Many of the people who might be expected to help with this operation are too sick with anthrax even to help themselves, let alone others. Lines at the distribution centers stretch around the block, with angry, frightened people pushing and shoving to get the life-saving drugs. Lines give way to mass unorganized crowds; soon they give way to frightened mob scenes. Several distribution centers have to be shut down after fights turn into riots.

Eventually, 20,000 will lose their lives; it is the worst man-made disaster in the history of the world.

This grim scenario and the mind-boggling estimates of death and illness caused by an airborne terrorist attack might seem outrageous — how, after all, could a single act wipe out as many people as are found in whole towns? But it is, in fact, a middle-of-the-road view of the kind of damage that an anthrax attack might cause. Remember that the Office of Technology Assessment estimated that just a couple of hundred pounds of anthrax spores released on a clear, calm night upwind of Washington, D.C., could kill 1 to 3 million people. This scenario is precisely the kind of case study that policy makers and public health officials are now beginning to give careful consideration.

In fact, many of the elements of the preceding scenario were drawn from a 1999 presentation at a bioterrorism conference sponsored by the Johns Hopkins Center for Civilian Biodefense Studies and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. I served on the planning committee for the conference, and we wanted to lay out in black and white what America could expect if an anthrax release occurred.

Descriere

In this fascinating book, one of the world's leading experts on bioterrorism dramatizes in detail what a viral war could unleash and exposes an American infrastructure that is unprepared to respond to such a threat. 256 p.