Logisch-philosophische Abhandlung: die Hundertjahrsausgabe: Anthem Studies in Wittgenstein

Autor Ludwig Wittgensteinen Limba Engleză Paperback – 10 mai 2021

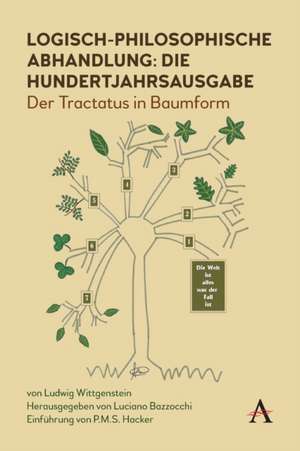

This renewed edition of the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, exactly a century after Wittgenstein's release, presents the text in a hierarchical manner, "which is the way in which the book was composed and in which Wittgenstein arranged (selected and supplemented) the best of the philosophical remarks that he had been writing since 1913" (Peter Hacker). That tree-like reading is recommended by Wittgenstein himself in the sole footnote of his book, in which he suggests that the inner logical structure of the text is set by the decimal numbers of its propositions. "They alone - the Author will add - give the book perspicuity and clearness, and without this numbering it would be an incomprehensible jumble". Indeed, the compact and intricate sequence of the traditional presentation is only a rigorous logical bet, but only a logical machine or a robot can unravel the tangle: for an ordinary human understanding that does not exploit its numbering, the book remains "an incomprehensible jumble".

In the present disposition, instead, all horizontal and vertical references become directly manifest and any reader can enjoy the fine architecture and the elegant reasoning of Wittgenstein's work. Every page is an actual reading unit, perfectly coherent and complete. The Tractatus becomes comprehensible also to unskilled readers, of course at more or less deep levels, while a scholar or a more practised reader can detect suggestions and meanings that had remained, until now, completely hidden. A historical note shows in which manner the new structural perspective sheds new light also in the compositional manuscript we have, which "writing units" are very similar, actually, to the pages of the present edition. Besides, this allows to rebuild the list of "Supplements" (here in the Appendix) that Wittgenstein gathered after he roughly finished his manuscript, but that he used very little in the final book.

Printing the Tractatus following Wittgenstein's decimal prescriptions required meticulous philological care and some discretional conventions: for instance, at the top of each page the commented-upon proposition is printed again, to make the sight complete and self-sufficient. On the other hand, some forcing of the text by the translators in their sequential reading could be eliminated, restoring a more literal translation. Also the famous and intriguing picture of the eye and its visual field (5.6331) has been restored as Wittgenstein drafted it, making the entire page perfectly understandable and coherent. This documented and editorial work on one of the most referenced books of the last century was conceived to obtain, and in fact gained, a perspicuous and crystal clear text, philologically faithful and relaxingly readable at the same time.

Din seria Anthem Studies in Wittgenstein

-

Preț: 115.61 lei

Preț: 115.61 lei -

Preț: 228.52 lei

Preț: 228.52 lei - 19%

Preț: 589.23 lei

Preț: 589.23 lei - 19%

Preț: 588.57 lei

Preț: 588.57 lei - 19%

Preț: 589.24 lei

Preț: 589.24 lei -

Preț: 228.38 lei

Preț: 228.38 lei -

Preț: 300.45 lei

Preț: 300.45 lei - 23%

Preț: 772.31 lei

Preț: 772.31 lei -

Preț: 306.04 lei

Preț: 306.04 lei - 23%

Preț: 694.74 lei

Preț: 694.74 lei - 23%

Preț: 694.88 lei

Preț: 694.88 lei - 23%

Preț: 694.00 lei

Preț: 694.00 lei -

Preț: 305.46 lei

Preț: 305.46 lei - 23%

Preț: 693.57 lei

Preț: 693.57 lei - 23%

Preț: 696.21 lei

Preț: 696.21 lei - 23%

Preț: 697.27 lei

Preț: 697.27 lei -

Preț: 260.42 lei

Preț: 260.42 lei - 23%

Preț: 696.21 lei

Preț: 696.21 lei - 23%

Preț: 696.65 lei

Preț: 696.65 lei - 19%

Preț: 647.05 lei

Preț: 647.05 lei -

Preț: 260.16 lei

Preț: 260.16 lei - 15%

Preț: 585.38 lei

Preț: 585.38 lei - 19%

Preț: 588.03 lei

Preț: 588.03 lei -

Preț: 228.52 lei

Preț: 228.52 lei

Preț: 303.17 lei

Nou

58.01€ • 60.72$ • 48.28£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 31 martie-14 aprilie

Specificații

ISBN-10: 1839982101

Pagini: 250

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 26 mm

Greutate: 0.41 kg

Editura: Anthem Press

Seria Anthem Studies in Wittgenstein