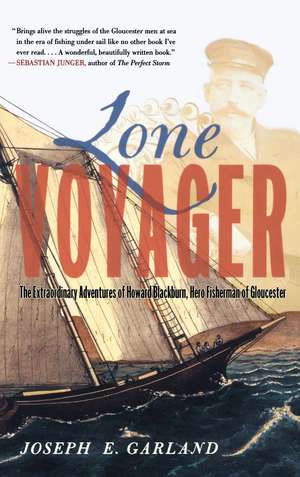

Lone Voyager: The Extraordinary Adventures Of Howard Blackburn Hero Fisherman Of Gloucester

Autor Joseph E Garlanden Limba Engleză Paperback – 20 noi 2000

Preț: 135.90 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 204

Preț estimativ în valută:

26.01€ • 27.35$ • 21.49£

26.01€ • 27.35$ • 21.49£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 27 martie-10 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780684872636

ISBN-10: 0684872633

Pagini: 336

Ilustrații: 57 b+w photos & maps

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.44 kg

Ediția:REV SUB

Editura: Touchstone Publishing

Colecția Touchstone

ISBN-10: 0684872633

Pagini: 336

Ilustrații: 57 b+w photos & maps

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.44 kg

Ediția:REV SUB

Editura: Touchstone Publishing

Colecția Touchstone

Notă biografică

Joseph E. Garland, a former newspaperman, has written extensively on social, maritime, and medical history, including thirteen books about Gloucester and Boston's North Shore and some 350 columns in the Gloucester Daily Times. A longtime sailor, he and his wife, Helen, live on the Eastern Point shore of Gloucester's outer harbor.

Extras

Chapter One: Dorymates

She sliced through the North Atlantic, nodding her head with the swell. The wind thundered off the taut curve of her sails, and she heeled away. Spray boomed from her plunging bow in cascades of exploding water. The sea poured over the rail and frothed along her lee deck and fell off past her quarters. The white wake boiled up under her counter as she surged on, and it simmered and faded astern, and the ocean was whole again.

The Gloucester schooner Grace L. Fears, queen of the fresh halibut fleet, was beating past the south shore of Nova Scotia. She was snug-rigged against the winter weather, her stately topmasts having been lowered and left home, along with her topsails and fisherman's staysail. But even her shortened canvas -- jib, jumbo, foresail and main -- was enough to put her deck under, and she rushed toward the fishing banks with a power that flung spume high into her rigging, where it froze and sparkled like crystal in the sun.

This two-masted beauty with the lines of a clipper ship was eighty-one feet from stem to stern, yet the proud lift of her bowsprit and the rakish slant of her fifty-six-foot mainboom made her look twice as long. With her sails flying and the ocean leaping from her forefoot, she was a sight to make the heart beat faster.

The master of this mistress, Captain Nathaniel Greenleaf, was the king of the halibut killers. The previous spring he and the Fears had brought home to Gloucester a fare of upwards of fifty tons in one record five weeks at sea, and it fetched the biggest money ever stocked on a single halibut trip in the history of the fisheries. The giant flounder, which sometimes attained a weight of 350 pounds, was in premium demand; competition among the schooners to be the first into market for the highest prices was fierce, and fierce risks were taken in its name. First fare meant top money for all hands, and a highliner like Greenleaf could hand-pick his crew from the ablest men on the coast.

But Skipper Nat was not aboard this trip. A few days earlier he had sailed the Fears into Liverpool, down below Halifax, to put an ailing member of the crew ashore; then he decided to swallow the anchor himself for a trip, at least, and turned the command over to Alec Griffin, his first mate and cook. Looking for new hands to make up his complement, Griffin met up with a young fisherman he had known from Gloucester who was spending the holidays in his home town of Port Medway down the coast. His name was Howard Blackburn, and he signed him on.

With a few thousand herring for bait and a load of ice in her hold to keep the catch fresh, the schooner cleared Liverpool on the twenty-first of January. Captain Griffin set a northeast course along the coast past Halifax and Cape Canso, around the cliffs of Cape Breton Island and into Cabot Strait, where the Gulf of St. Lawrence loses itself in the Atlantic off Newfoundland's south shore. The hunting ground he sought was Burgeo Bank, a mound on the ocean floor, dwarfed by the broad underwater mesa of the Grand Banks directly to the eastward and bigger than Newfoundland itself.

At the swirling junctions of the Gulf Stream and the Labrador Current the wandering silt had settled to build the shallow banks; the mixing of the waters, warm and cold, created on the ocean's bottom a feeding farm for fish by the billion, and on its surface a turbulent wilderness, now white from the lash of the gale, now black with the stealth of the fog.

Burgeo Bank lay sixty miles south of the fjords of Newfoundland, and on Burgeo lurked the prey.

The Fears sailed over the southern slope of Burgeo during the night of the twenty-fourth, three days out of Nova Scotia. Alec Griffin hove the lead rhythmically, fingering his way along the floor a hundred fathoms below. The lead line chopped off the chart depth. But only the tallow told where the fish would be. As the bob plunked to the bottom, a sticky plug of it picked up samples of mud and sand so typical that when it was hand-over-handed back aboard, an old salt -- eyeing, feeling, smelling, tasting the soil of the sea -- could lay his mark on infinity and not miss by a hundred yards.

By daybreak the skipper had found his spot below. He threw the wheel hard over and brought the schooner into the wind. The anchor splashed off the bow, and the men, heavy in their oilskins, pulled down the wings of snapping canvas.

Amidships, the fishing dories were nested in stacks to port and starboard. A hoist from the mainmast was snapped to the rope handle, the becket, in the stern of the topmost, another from the foremast to the becket of the painter; with a heave the men swung the dory up and out of the nest and lowered it to the deck.

These eighteen-foot dories were double-ended, slope-sided, flat-bottomed, open boats -- mighty tippy-looking to brave the waves. The thwarts (seats) were removable so they could be "nested" -- stacked on either side of the deck to save space -- and the heavy oars of stiff spruce were ten feet long. The bank dory was built to take a beating.

Trawl tubs and gear were hove aboard, and with one more haul on the hoists and a shove from the deck, the dory swung over the rail, dropped into the sea and bobbed, like a cork until its crew of two jumped in, cast off the lines and bent to the oars. Their weight gave it stability, and a load of fish would give it even more; yet it was steadiest when it was tipping, and the farther it leaned -- even to the gunwale -- the more stable it would be...a strange boat.

Five more dories were loaded and lowered away. The six crews had drawn lots for position and rowed out from the Fears across the wind, which was coming light from the southeast. The sea ran easy. The dawn of the north was about to leap from the night. The cold was bitter.

Tom Welch, a husky Newfoundland lad with tousled hair and a broad, cheerful face, had been assigned the newcomer Blackburn as his dorymate. As they swung away from the schooner, rowing in powerful unison, he watched with satisfaction the sweep of the oars in the big man's hands.

When each dory had reached its position on the line, the crew shipped their oars and prepared to set the trawl. All were fishing against the light breeze in parallel lanes. This way, when it came time to haul, they would pick up the far end of the trawl first, and the wind would help them back to the ship.

One man went forward and dropped the trawl anchor overboard, paying the trawl out of the first tub until the anchor hit bottom. Next went the keg buoy, topped with a flag and attached to the anchor by a separate line. The trawl was a tarred cotton rope the thickness of a pencil, coiled in the tubs in fifty-fathom sections called skates, six skates to a tub, four tubs to a dory. At fifteen-foot intervals ganging lines were tied to the trawl, four feet long, a baited hook at the end of each. The hooks were flicked out of the tub with a supple stick as the trawl spun off the coil. As each skate went over the side, the ends were knotted, one to the next, from tub to tub, until nearly a mile and a half of trawl and 480 hooks lay on the ocean floor. When the last of the trawl was reached, a second anchor and buoy were dropped over.

After setting, the men rowed their dories back to the schooner for a mug-up. The rest was up to the fish; twenty-nine hundred innocent-looking dinners were awaiting them in the murk of Burgeo Bank.

But in only two hours Skipper Alec ordered his crew back over the side. There was a feel to the heavy air and a look to the sky that meant wind. Fish or no, the trawls would have to be hauled before their time. The catch would be thin, but he wanted none of his dories caught in a nasty sea away from their vessel.

Just as the boats shoved off, the first snowflakes fluttered down. The wind had died to a breath. The sky was leaden and faded into the smooth gray sea at the horizon. For the second time this morning the men left the schooner astern, heading now for the outermost buoys.

Welch and Blackburn drove their dory with surging strokes through the glassy sea. The snow was coming a little thicker. Some of the others had already reached their markers and were commencing to haul as the two men passed. A few more strokes, and they glided up to the keg and pulled it aboard. Up came the buoy rope, then the anchor and the end of the trawl. Welch hove the heavy line up on the gurdy, a metal roller set on a pin in the port gunwale of the bow. Blackburn stood in the waist, his killer club at the ready.

The gurdy twirled and the water spun from the line as Welch hauled in the straining trawl. It jerked and jumped in his grip. A thrashing halibut broke the surface. Blackburn seized the ganging line, yanked the big, flat, flapping fish to the gunwale and clubbed it on the head. He dragged it over the side, worked the hook from its mouth with his killer and dropped the quivering body in the bottom. Then he coiled the freed line in the tub, while his dorymate turned back to the trawl.

When half a mile of trawl was back aboard, and a few fish slithered in the bilge, the two paused to remark that the southeast breeze was freshening. But this was all right, since it favored them all the more as they worked their way toward the Fears. They could see the nearest dories through the snow, ahead of them with the hauling. They returned to their task.

Just as they fetched the second buoy, the wind fell back to a flat calm, ominously. The other men were already pulling for the schooner. Blackburn and Welch got the last of the trawl aboard, grabbed the oars and headed for their ship.

Then the squall hit. But it came from the wrong direction, from the northwest, as they had feared. Now they were to leeward of the vessel, fighting the wind. In an instant the schooner was out of sight in the flying snow...they weren't sure where; the sudden shift had fouled their bearings.

As the snow thickened, the wind increased. It kicked the sea into a chop, flicking spindrift from the whitecaps. The wind-driven snow and spray blasted against their oilskins. A few dory lengths away the ocean disappeared behind a dizzy, whirling curtain of white. It was as if they were rowing with all their might against a rock.

After an hour's hard pulling they agreed that they must have passed beyond their objective and could only be to windward of her; they might have rowed on by within a few yards without seeing the ghostly vessel or hearing her horn above the shrieking gale. They decided the smart thing was to anchor and wait for the snow to let up; then they would be able to see the schooner and could make an easy job of rowing back to her with a following wind.

Soon after darkness the snow came to an end. There, not downwind as they had expected but as far to the windward as ever, they saw the torch raised in the shrouds of the Fears to guide them home. They had been rowing on an ocean treadmill.

They broke out the anchor and strained for the flare. But the wind was too fierce and the sea too rough; they made no more headway against the combination than before. Again they threw over the anchor. At first it refused to take a bite, and the dory drifted to leeward. Suddenly it caught on the bottom and fetched them up short. Head to the wind, the dory backed off tight against the line, bouncing up in each trough and plowing into every wave; water poured in over the bow.

Welch dove for the bailing scoop and flailed at the rising water. But it was useless; the sea crashed into the boat faster than he could throw it back. They kicked in the head of a buoy keg and, using it as a bucket, were just able to dump the ocean out as it swept aboard.

The gale honed the edge of the cold. Spray froze where it struck and glazed the dory in a gnarled plate of ice. The boat grew churlish under the burden and settled lumpishly into the sea. They hove the trawls and tubs over the side and all the fish save a cod; they could eat him raw if it came to that.

Now and again during the wild night an obliging sea lifted them high on its back, and for a hovering instant they glimpsed the dim spark of the torch before they were plunged back into the valley of the trough.

At dawn there was nothing to see but the frenzy of the waves, nothing to hear but the scream of the gale.

Newfoundland lay somewhere to the north -- sixty miles, maybe more. They were big men, tough from hardship. Blackburn was twenty-three years old; he stood six feet two, weighed over two hundred pounds, and was all bone and muscle. Welch was younger and not so heavy, but strong and full of the will to live. They would have all they could do to keep afloat. There was neither food nor fresh water, only the codfish, by now frozen stiff. The cold was intense.

Again they broke out the anchor and tried to row, this time for the coast. It was no use. The seas were running so high that at any instant a cresting giant might suck them in, flip them over and bury all in a thundering avalanche of water.

And so they gave it up. While Welch kept the dory head to the wind and sea with the oars, Blackburn kicked in the head of the other keg buoy and tried to tie the end of the bow painter to its flagstaff. His thick mittens made him clumsy; he pulled them off and dropped them in the bilge to keep them from freezing. When he had made the painter fast to the buoy's staff, he pulled the gurdy from the gunwale and tied it to the keg to weight it down. Then he threw this sea anchor overboard. The open end of the keg cupped against the water and kept enough tension on the line to hold their bow to the wind and the oncoming seas.

The boat was filling with water. The instant the drag stretched the painter to its length and swung them head to the waves, Welch shipped his oars, seized the bailing keg and turned to furiously.

With his first bailerful, the mittens went over the side. Neither man noticed until Welch paused for breath and Blackburn began searching through the slosh of the bilge. They were gone. There was no helping it. He took his turn with the bailer.

For an hour or more they bailed. Blackburn hardly missed the sodden mittens until his dorymate remarked that his hands looked peculiar. They were the ashen gray of a cadaver. Although his hands were frigid to the touch, the only sensation Blackburn felt was numbness. He knew that soon the tissues would crystallize to ice, and his fingers would be casts of frozen flesh encasing bone. Without fingers, without hands, he would be a dead weight in the dory, a grotesque cargo. What if a vessel should chance by and save them? It would find Tom at the oars, and him crouched helpless on a thwart, his hands as stiff as sticks.

He leaned over and picked up his oars. Slowly, slowly, he bent the resisting fingers and thumbs around the handles. In twenty minutes they were frozen claws. He slipped them off, replaced the oars in the bottom and took his turn bailing.

All that second day the two men spelled each other bailing and pounding ice with the killer. It froze as fast as they knocked it off. Blackburn could hardly grasp the club. He held it so crudely that sometimes the claw of his hand itself smashed down on the jagged crusts.

Welch was a game man. He would often say -- don't give up, we will soon be picked up. But a vessel could have passed within fifty yards of us and not see us as the vapor was so thick, and the boat shipped so much water and made ice so fast that it kept one of us busy about all the time, and he knew as well as I did that no vessel would be moving about in such weather.

Blackburn had missed the ice so often with the killer that the little finger of his right hand was pulpy. He kicked away his right boot, worked the sock off and put his bare foot back in. With his teeth, he drew the stocking over the swollen hand, but it stuck at the turn of the heel. Each time he dipped the bailer, the toe of the sock dragged through the water. A ball of ice formed in the toe and grew so heavy it pulled the stocking down with every sweep of his arm. Each time he worked it back on with his teeth. In exasperation he whacked the lumpy toe across the gunwale to break the ice. The sock flipped off and disappeared. He had robbed his foot in a vain attempt to save his hand.

It was my turn just before dark, and after bailing out the boat I was just about to lie down in the bow with Welch so to get a little shelter from the wind, which cut us like a knife, when a sea broke on the boat, half filling her. It was now Welch's turn to bail, but he made no attempt to get up, and when I said -- Tom, jump quick, he said -- I can't see. As the water had to be bailed out before another sea broke on her, there was no time for an argument, so I jumped up and bailed out the water. I then said -- Tom this won't do. You must do your part. Your hands are not frozen and beating to pieces like mine -- showing him my hand with the little finger just hanging by the skin between the fingers. I have always been sorry that I showed him the hand, for he gave up altogether then and said -- Howard, what is the use, we can't live until morning, and might as well go first as last.

Blackburn shook his head. He told his weakening dorymate to shove over, and lay back in the bow beside him.

The seas engulfed them in the blackness of the second night, and the gale drove the spray like bullets across the bow. He bailed ceaselessly, flopping down with Welch only long enough to catch his breath before stumbling back to the battle.

Tom was slipping away. Once he roused himself and put his feet over the side into the sea. Blackburn lifted them back and settled him in his place; then he decided to turn over the bow to him altogether and moved to the stern. Tom asked for a drink of water, over and over. He asked for a piece of ice. Blackburn picked a salty chunk from the bilge and handed it to him; he bit some off and threw the rest away.

As cold crept in and life seeped out, he moaned and muttered, a dark and shapeless form in the pounding bow. Once he mumbled something that sounded like a prayer; twice he called out to Blackburn by name.

But the big man had all he could do to keep the dory from sinking. The crash of breaking seas and the thunder of wind and spray beat down the groans from the bow. About two hours after dark he called to Tom. There was no stir or sound.

He stumbled forward, tilted back the lolling head and peered down into the white, wet face, into the staring eyes. His dorymate was dead.

There was a lull in the heaving sea. He picked up the body, staggered aft and dropped it in the stern. He clawed off one of the mittens and tried to put it on. But his hand was too swollen and distorted. The freezing spray wrapped the body in a winding sheet of ice. Its weight raised the bow and steadied the boat. It was ballast.

For the rest of the night he bailed and pounded ice. When he could, he slumped into the bow, his claws between his legs and his face down out of the wind and spray. Then a wave would flood the boat, and he would drag himself back to the bailing.

Before dawn of the third day the wind died, and the seas subsided. By sunrise the ocean was nearly calm. The dory rose and fell on the long swells, and the cold relaxed its bite to a grinding gnaw.

His mouth and throat were dry, and his tongue was thick, but he felt no hunger. He pulled in the drag. A pair of oars had been lost overboard during the storm; a pair remained. He set them in the wooden tholepins in the gunwales and forced the claws over the handles. The dory was a gross sculpture of ice, ponderous as a barge to row.

He shipped the oars and pounded the planks with one until the armor plates of ice worked loose and splashed into the sea. Where the becket of the painter looped through the bow, rope and wood were welded by a solid hunk of ice. When he struck it with the oar, and it fell away, he found that two of the rope's three strands had parted. The bond of ice had saved the drag that night, and the drag had saved him.

With clumsy claws he repaired the painter. Then he worked them back on the oars and resumed rowing...for Newfoundland.

By noon the steady twist of the oars had worn away the insides of his fingers. First the skin, then the frozen flesh crumbled off in a dry powder, and then the wood was rasping on the bones.

The friction of the oar handles had wore away so much flesh from the inside of my hands that I could hardly hold the oars, and often my hands would slip off the ends of the oars. When I, forgetting that I could not open my hands, would make a grab for the oar handle and when the backs of my fingers would strike the oar, it would sound just like so many sticks.

So to hold the oars I had to put the outside of each hand upon the thick part of the oar, and by so doing the oarhandles would stick out between my forefinger and thumb two or three inches. When bending forward to take a stroke I would keep one hand a little higher than the other, but sometimes I would forget and take a stroke as if my hands were all right. Then the end of the oar would strike the side of my hand and knock off a piece of flesh as big around as a fifty cent piece, and fully three times as thick. The blood would just show and then seem to freeze.

He rowed thus all day. His thirst increased, but still not his hunger. Just before dusk, far out on the horizon, he saw what appeared to be a great rock covered with snow. He pulled on until dark. Afraid of losing the oars overboard in the night if he kept on rowing, he dropped the drag over and huddled in the bottom to await daylight.

0 The wind arose and blew hard during the third night, but the dory shipped little water. To keep awake and warm he hooked his arms around a thwart and rocked back and forth, back and forth. The night was long, and Tom was poor company.

At dawn of the fourth day, Sunday, he hauled in the drag and bent again to the oars. The night wind had expired. The sea was calm, and the cold was not so sharp. What he had taken to be a massive rock the previous evening turned out to be an island, cloaked with snow.

He rested on the oars and inspected it. There were no signs of life, neither harbor nor house. He concluded it was barren, and since it lay away from where he presumed the mainland to be, he oared on by.

All morning he rowed and in the early afternoon passed a cluster of rocks jutting out of the sea. All afternoon he rowed in a sort of perpetual motion easier to maintain than stop. Now and then he glanced over his shoulder without breaking the clockwork of his body and the oars.

Late in the afternoon a white stretch of coast rose thinly out of the horizon.

He rowed on.

At the edge of dusk the dory moved into a strong tide rip. The ocean was black and turbulent from the seaward surge of a brackish current, out and over the incoming tide. He figured he was outside the mouth of a rapidly emptying river. The boat was buffeted by the maelstrom of opposing waters, and he struggled on. Now he could see the outline of the narrow entrance. Sheer rock portals overhung with snow climbed a quarter of a mile out of the banging surf.

At dusk the wind arose, and the sea erupted into whitecaps. Every stroke an agony, he fought the current and crawled through the narrows. The bluffs towered over him. He dared not miss even a stroke lest the river disgorge him back to the sea.

Searching the snow-laden banks in the last glimmer of twilight as he rowed, his eyes stopped at a broken wharf with a shed on it. Beyond, on the shore, was a hut, steeped in snow, silent and deserted.

His thirst rushed in on him.

I could tell by the color of the water running out that fresh water could be found if I could only row up the river against the tide, and at that time I would give ten years of my life for a drink of water. I rowed some distance up the river, when all at once my mind gave way. I seemed to think that some former shipmates was laughing at the little headway I was making.

Abruptly, he turned back and rowed for the wharf and the lifeless hut.

The moon had risen, and by its frigid light he worked up to the landing. Next to it the waves were breaking against a flat rock. He guided the dory alongside, shipped the oars and stood up. His hips and knees crackled, and he nearly fell as he stepped out. He hooked an arm through the becket, pulled the boat partway onto the rock and hove the drag over the wharf. Then he clambered up himself.

The deadness in his feet told him they were frozen.

He stumbled into the shed and found a barrel half full of salt codfish. Sure that if he ate some now the salt would drive him crazy, he broke through the ice on top and buried a couple in the snow, hoping it would draw out the salt and freshen them by morning. The thought of the fish in the dory never crossed his mind.

He waded through the snow to the hut and pushed in the rotten door. The roof was patched with sky, and the snow on the dirt floor came up to his knees. There was a table in one room, a bedstead in the other, both drifted with snow.

As he turned back to the doorway, his eyes wandered toward the river narrows and out beyond to the ocean. There, in the frame of the cliffs, a silhouette against the moonlit sea, was a schooner passing to the east. It had not been in view when he entered the river, and he thought it must be making for a harbor not far away. He resolved to spend the night in the shack and at daybreak to get back in the dory, row out of the river and search for life to the eastward.

He clawed the boards from the bed, brushed away the snow and turned them over for something dry to lie on. In a corner he found some fishlines rolled up on reels. A torn net hung from a beam. He put the lines and reels at the head of the bed for a pillow, lay down and drew the net over his body.

The cold pierced him. He shivered so, he thought his teeth would break, and every muscle in his body joined the uncontrollable contagion of his shaking. The cold, the stillness, the total fatigue were a curtain closing around his consciousness. His very eyelids begged for rest. But he knew that if he slept he would not wake.

Pushing the net away, he dragged himself from the boards and walked the drifted floor, eating snow from the table; the more he ate, the more he craved. All that fourth night he walked the floor and ate the snow, and his thirst was merciless.

The earliest light of the fifth day brought him outside. He floundered through the drifts back to the wharf. The night wind had moderated, but before it fell off it had pushed the sea up into the river and against the shore.

The dory was awash with water. Tom was a weird shape in the bottom. The thwarts and the oars revolved in an eddy under the wharf.

The waves had pounded the boat against the rock, knocking the plug from the drainhole, and the water had poured up through. One plank below the port waterline was splintered; another, under the gunwale, was smashed.

Copyright © 2000 by Simon & Schuster

She sliced through the North Atlantic, nodding her head with the swell. The wind thundered off the taut curve of her sails, and she heeled away. Spray boomed from her plunging bow in cascades of exploding water. The sea poured over the rail and frothed along her lee deck and fell off past her quarters. The white wake boiled up under her counter as she surged on, and it simmered and faded astern, and the ocean was whole again.

The Gloucester schooner Grace L. Fears, queen of the fresh halibut fleet, was beating past the south shore of Nova Scotia. She was snug-rigged against the winter weather, her stately topmasts having been lowered and left home, along with her topsails and fisherman's staysail. But even her shortened canvas -- jib, jumbo, foresail and main -- was enough to put her deck under, and she rushed toward the fishing banks with a power that flung spume high into her rigging, where it froze and sparkled like crystal in the sun.

This two-masted beauty with the lines of a clipper ship was eighty-one feet from stem to stern, yet the proud lift of her bowsprit and the rakish slant of her fifty-six-foot mainboom made her look twice as long. With her sails flying and the ocean leaping from her forefoot, she was a sight to make the heart beat faster.

The master of this mistress, Captain Nathaniel Greenleaf, was the king of the halibut killers. The previous spring he and the Fears had brought home to Gloucester a fare of upwards of fifty tons in one record five weeks at sea, and it fetched the biggest money ever stocked on a single halibut trip in the history of the fisheries. The giant flounder, which sometimes attained a weight of 350 pounds, was in premium demand; competition among the schooners to be the first into market for the highest prices was fierce, and fierce risks were taken in its name. First fare meant top money for all hands, and a highliner like Greenleaf could hand-pick his crew from the ablest men on the coast.

But Skipper Nat was not aboard this trip. A few days earlier he had sailed the Fears into Liverpool, down below Halifax, to put an ailing member of the crew ashore; then he decided to swallow the anchor himself for a trip, at least, and turned the command over to Alec Griffin, his first mate and cook. Looking for new hands to make up his complement, Griffin met up with a young fisherman he had known from Gloucester who was spending the holidays in his home town of Port Medway down the coast. His name was Howard Blackburn, and he signed him on.

With a few thousand herring for bait and a load of ice in her hold to keep the catch fresh, the schooner cleared Liverpool on the twenty-first of January. Captain Griffin set a northeast course along the coast past Halifax and Cape Canso, around the cliffs of Cape Breton Island and into Cabot Strait, where the Gulf of St. Lawrence loses itself in the Atlantic off Newfoundland's south shore. The hunting ground he sought was Burgeo Bank, a mound on the ocean floor, dwarfed by the broad underwater mesa of the Grand Banks directly to the eastward and bigger than Newfoundland itself.

At the swirling junctions of the Gulf Stream and the Labrador Current the wandering silt had settled to build the shallow banks; the mixing of the waters, warm and cold, created on the ocean's bottom a feeding farm for fish by the billion, and on its surface a turbulent wilderness, now white from the lash of the gale, now black with the stealth of the fog.

Burgeo Bank lay sixty miles south of the fjords of Newfoundland, and on Burgeo lurked the prey.

The Fears sailed over the southern slope of Burgeo during the night of the twenty-fourth, three days out of Nova Scotia. Alec Griffin hove the lead rhythmically, fingering his way along the floor a hundred fathoms below. The lead line chopped off the chart depth. But only the tallow told where the fish would be. As the bob plunked to the bottom, a sticky plug of it picked up samples of mud and sand so typical that when it was hand-over-handed back aboard, an old salt -- eyeing, feeling, smelling, tasting the soil of the sea -- could lay his mark on infinity and not miss by a hundred yards.

By daybreak the skipper had found his spot below. He threw the wheel hard over and brought the schooner into the wind. The anchor splashed off the bow, and the men, heavy in their oilskins, pulled down the wings of snapping canvas.

Amidships, the fishing dories were nested in stacks to port and starboard. A hoist from the mainmast was snapped to the rope handle, the becket, in the stern of the topmost, another from the foremast to the becket of the painter; with a heave the men swung the dory up and out of the nest and lowered it to the deck.

These eighteen-foot dories were double-ended, slope-sided, flat-bottomed, open boats -- mighty tippy-looking to brave the waves. The thwarts (seats) were removable so they could be "nested" -- stacked on either side of the deck to save space -- and the heavy oars of stiff spruce were ten feet long. The bank dory was built to take a beating.

Trawl tubs and gear were hove aboard, and with one more haul on the hoists and a shove from the deck, the dory swung over the rail, dropped into the sea and bobbed, like a cork until its crew of two jumped in, cast off the lines and bent to the oars. Their weight gave it stability, and a load of fish would give it even more; yet it was steadiest when it was tipping, and the farther it leaned -- even to the gunwale -- the more stable it would be...a strange boat.

Five more dories were loaded and lowered away. The six crews had drawn lots for position and rowed out from the Fears across the wind, which was coming light from the southeast. The sea ran easy. The dawn of the north was about to leap from the night. The cold was bitter.

Tom Welch, a husky Newfoundland lad with tousled hair and a broad, cheerful face, had been assigned the newcomer Blackburn as his dorymate. As they swung away from the schooner, rowing in powerful unison, he watched with satisfaction the sweep of the oars in the big man's hands.

When each dory had reached its position on the line, the crew shipped their oars and prepared to set the trawl. All were fishing against the light breeze in parallel lanes. This way, when it came time to haul, they would pick up the far end of the trawl first, and the wind would help them back to the ship.

One man went forward and dropped the trawl anchor overboard, paying the trawl out of the first tub until the anchor hit bottom. Next went the keg buoy, topped with a flag and attached to the anchor by a separate line. The trawl was a tarred cotton rope the thickness of a pencil, coiled in the tubs in fifty-fathom sections called skates, six skates to a tub, four tubs to a dory. At fifteen-foot intervals ganging lines were tied to the trawl, four feet long, a baited hook at the end of each. The hooks were flicked out of the tub with a supple stick as the trawl spun off the coil. As each skate went over the side, the ends were knotted, one to the next, from tub to tub, until nearly a mile and a half of trawl and 480 hooks lay on the ocean floor. When the last of the trawl was reached, a second anchor and buoy were dropped over.

After setting, the men rowed their dories back to the schooner for a mug-up. The rest was up to the fish; twenty-nine hundred innocent-looking dinners were awaiting them in the murk of Burgeo Bank.

But in only two hours Skipper Alec ordered his crew back over the side. There was a feel to the heavy air and a look to the sky that meant wind. Fish or no, the trawls would have to be hauled before their time. The catch would be thin, but he wanted none of his dories caught in a nasty sea away from their vessel.

Just as the boats shoved off, the first snowflakes fluttered down. The wind had died to a breath. The sky was leaden and faded into the smooth gray sea at the horizon. For the second time this morning the men left the schooner astern, heading now for the outermost buoys.

Welch and Blackburn drove their dory with surging strokes through the glassy sea. The snow was coming a little thicker. Some of the others had already reached their markers and were commencing to haul as the two men passed. A few more strokes, and they glided up to the keg and pulled it aboard. Up came the buoy rope, then the anchor and the end of the trawl. Welch hove the heavy line up on the gurdy, a metal roller set on a pin in the port gunwale of the bow. Blackburn stood in the waist, his killer club at the ready.

The gurdy twirled and the water spun from the line as Welch hauled in the straining trawl. It jerked and jumped in his grip. A thrashing halibut broke the surface. Blackburn seized the ganging line, yanked the big, flat, flapping fish to the gunwale and clubbed it on the head. He dragged it over the side, worked the hook from its mouth with his killer and dropped the quivering body in the bottom. Then he coiled the freed line in the tub, while his dorymate turned back to the trawl.

When half a mile of trawl was back aboard, and a few fish slithered in the bilge, the two paused to remark that the southeast breeze was freshening. But this was all right, since it favored them all the more as they worked their way toward the Fears. They could see the nearest dories through the snow, ahead of them with the hauling. They returned to their task.

Just as they fetched the second buoy, the wind fell back to a flat calm, ominously. The other men were already pulling for the schooner. Blackburn and Welch got the last of the trawl aboard, grabbed the oars and headed for their ship.

Then the squall hit. But it came from the wrong direction, from the northwest, as they had feared. Now they were to leeward of the vessel, fighting the wind. In an instant the schooner was out of sight in the flying snow...they weren't sure where; the sudden shift had fouled their bearings.

As the snow thickened, the wind increased. It kicked the sea into a chop, flicking spindrift from the whitecaps. The wind-driven snow and spray blasted against their oilskins. A few dory lengths away the ocean disappeared behind a dizzy, whirling curtain of white. It was as if they were rowing with all their might against a rock.

After an hour's hard pulling they agreed that they must have passed beyond their objective and could only be to windward of her; they might have rowed on by within a few yards without seeing the ghostly vessel or hearing her horn above the shrieking gale. They decided the smart thing was to anchor and wait for the snow to let up; then they would be able to see the schooner and could make an easy job of rowing back to her with a following wind.

Soon after darkness the snow came to an end. There, not downwind as they had expected but as far to the windward as ever, they saw the torch raised in the shrouds of the Fears to guide them home. They had been rowing on an ocean treadmill.

They broke out the anchor and strained for the flare. But the wind was too fierce and the sea too rough; they made no more headway against the combination than before. Again they threw over the anchor. At first it refused to take a bite, and the dory drifted to leeward. Suddenly it caught on the bottom and fetched them up short. Head to the wind, the dory backed off tight against the line, bouncing up in each trough and plowing into every wave; water poured in over the bow.

Welch dove for the bailing scoop and flailed at the rising water. But it was useless; the sea crashed into the boat faster than he could throw it back. They kicked in the head of a buoy keg and, using it as a bucket, were just able to dump the ocean out as it swept aboard.

The gale honed the edge of the cold. Spray froze where it struck and glazed the dory in a gnarled plate of ice. The boat grew churlish under the burden and settled lumpishly into the sea. They hove the trawls and tubs over the side and all the fish save a cod; they could eat him raw if it came to that.

Now and again during the wild night an obliging sea lifted them high on its back, and for a hovering instant they glimpsed the dim spark of the torch before they were plunged back into the valley of the trough.

At dawn there was nothing to see but the frenzy of the waves, nothing to hear but the scream of the gale.

Newfoundland lay somewhere to the north -- sixty miles, maybe more. They were big men, tough from hardship. Blackburn was twenty-three years old; he stood six feet two, weighed over two hundred pounds, and was all bone and muscle. Welch was younger and not so heavy, but strong and full of the will to live. They would have all they could do to keep afloat. There was neither food nor fresh water, only the codfish, by now frozen stiff. The cold was intense.

Again they broke out the anchor and tried to row, this time for the coast. It was no use. The seas were running so high that at any instant a cresting giant might suck them in, flip them over and bury all in a thundering avalanche of water.

And so they gave it up. While Welch kept the dory head to the wind and sea with the oars, Blackburn kicked in the head of the other keg buoy and tried to tie the end of the bow painter to its flagstaff. His thick mittens made him clumsy; he pulled them off and dropped them in the bilge to keep them from freezing. When he had made the painter fast to the buoy's staff, he pulled the gurdy from the gunwale and tied it to the keg to weight it down. Then he threw this sea anchor overboard. The open end of the keg cupped against the water and kept enough tension on the line to hold their bow to the wind and the oncoming seas.

The boat was filling with water. The instant the drag stretched the painter to its length and swung them head to the waves, Welch shipped his oars, seized the bailing keg and turned to furiously.

With his first bailerful, the mittens went over the side. Neither man noticed until Welch paused for breath and Blackburn began searching through the slosh of the bilge. They were gone. There was no helping it. He took his turn with the bailer.

For an hour or more they bailed. Blackburn hardly missed the sodden mittens until his dorymate remarked that his hands looked peculiar. They were the ashen gray of a cadaver. Although his hands were frigid to the touch, the only sensation Blackburn felt was numbness. He knew that soon the tissues would crystallize to ice, and his fingers would be casts of frozen flesh encasing bone. Without fingers, without hands, he would be a dead weight in the dory, a grotesque cargo. What if a vessel should chance by and save them? It would find Tom at the oars, and him crouched helpless on a thwart, his hands as stiff as sticks.

He leaned over and picked up his oars. Slowly, slowly, he bent the resisting fingers and thumbs around the handles. In twenty minutes they were frozen claws. He slipped them off, replaced the oars in the bottom and took his turn bailing.

All that second day the two men spelled each other bailing and pounding ice with the killer. It froze as fast as they knocked it off. Blackburn could hardly grasp the club. He held it so crudely that sometimes the claw of his hand itself smashed down on the jagged crusts.

Welch was a game man. He would often say -- don't give up, we will soon be picked up. But a vessel could have passed within fifty yards of us and not see us as the vapor was so thick, and the boat shipped so much water and made ice so fast that it kept one of us busy about all the time, and he knew as well as I did that no vessel would be moving about in such weather.

Blackburn had missed the ice so often with the killer that the little finger of his right hand was pulpy. He kicked away his right boot, worked the sock off and put his bare foot back in. With his teeth, he drew the stocking over the swollen hand, but it stuck at the turn of the heel. Each time he dipped the bailer, the toe of the sock dragged through the water. A ball of ice formed in the toe and grew so heavy it pulled the stocking down with every sweep of his arm. Each time he worked it back on with his teeth. In exasperation he whacked the lumpy toe across the gunwale to break the ice. The sock flipped off and disappeared. He had robbed his foot in a vain attempt to save his hand.

It was my turn just before dark, and after bailing out the boat I was just about to lie down in the bow with Welch so to get a little shelter from the wind, which cut us like a knife, when a sea broke on the boat, half filling her. It was now Welch's turn to bail, but he made no attempt to get up, and when I said -- Tom, jump quick, he said -- I can't see. As the water had to be bailed out before another sea broke on her, there was no time for an argument, so I jumped up and bailed out the water. I then said -- Tom this won't do. You must do your part. Your hands are not frozen and beating to pieces like mine -- showing him my hand with the little finger just hanging by the skin between the fingers. I have always been sorry that I showed him the hand, for he gave up altogether then and said -- Howard, what is the use, we can't live until morning, and might as well go first as last.

Blackburn shook his head. He told his weakening dorymate to shove over, and lay back in the bow beside him.

The seas engulfed them in the blackness of the second night, and the gale drove the spray like bullets across the bow. He bailed ceaselessly, flopping down with Welch only long enough to catch his breath before stumbling back to the battle.

Tom was slipping away. Once he roused himself and put his feet over the side into the sea. Blackburn lifted them back and settled him in his place; then he decided to turn over the bow to him altogether and moved to the stern. Tom asked for a drink of water, over and over. He asked for a piece of ice. Blackburn picked a salty chunk from the bilge and handed it to him; he bit some off and threw the rest away.

As cold crept in and life seeped out, he moaned and muttered, a dark and shapeless form in the pounding bow. Once he mumbled something that sounded like a prayer; twice he called out to Blackburn by name.

But the big man had all he could do to keep the dory from sinking. The crash of breaking seas and the thunder of wind and spray beat down the groans from the bow. About two hours after dark he called to Tom. There was no stir or sound.

He stumbled forward, tilted back the lolling head and peered down into the white, wet face, into the staring eyes. His dorymate was dead.

There was a lull in the heaving sea. He picked up the body, staggered aft and dropped it in the stern. He clawed off one of the mittens and tried to put it on. But his hand was too swollen and distorted. The freezing spray wrapped the body in a winding sheet of ice. Its weight raised the bow and steadied the boat. It was ballast.

For the rest of the night he bailed and pounded ice. When he could, he slumped into the bow, his claws between his legs and his face down out of the wind and spray. Then a wave would flood the boat, and he would drag himself back to the bailing.

Before dawn of the third day the wind died, and the seas subsided. By sunrise the ocean was nearly calm. The dory rose and fell on the long swells, and the cold relaxed its bite to a grinding gnaw.

His mouth and throat were dry, and his tongue was thick, but he felt no hunger. He pulled in the drag. A pair of oars had been lost overboard during the storm; a pair remained. He set them in the wooden tholepins in the gunwales and forced the claws over the handles. The dory was a gross sculpture of ice, ponderous as a barge to row.

He shipped the oars and pounded the planks with one until the armor plates of ice worked loose and splashed into the sea. Where the becket of the painter looped through the bow, rope and wood were welded by a solid hunk of ice. When he struck it with the oar, and it fell away, he found that two of the rope's three strands had parted. The bond of ice had saved the drag that night, and the drag had saved him.

With clumsy claws he repaired the painter. Then he worked them back on the oars and resumed rowing...for Newfoundland.

By noon the steady twist of the oars had worn away the insides of his fingers. First the skin, then the frozen flesh crumbled off in a dry powder, and then the wood was rasping on the bones.

The friction of the oar handles had wore away so much flesh from the inside of my hands that I could hardly hold the oars, and often my hands would slip off the ends of the oars. When I, forgetting that I could not open my hands, would make a grab for the oar handle and when the backs of my fingers would strike the oar, it would sound just like so many sticks.

So to hold the oars I had to put the outside of each hand upon the thick part of the oar, and by so doing the oarhandles would stick out between my forefinger and thumb two or three inches. When bending forward to take a stroke I would keep one hand a little higher than the other, but sometimes I would forget and take a stroke as if my hands were all right. Then the end of the oar would strike the side of my hand and knock off a piece of flesh as big around as a fifty cent piece, and fully three times as thick. The blood would just show and then seem to freeze.

He rowed thus all day. His thirst increased, but still not his hunger. Just before dusk, far out on the horizon, he saw what appeared to be a great rock covered with snow. He pulled on until dark. Afraid of losing the oars overboard in the night if he kept on rowing, he dropped the drag over and huddled in the bottom to await daylight.

0 The wind arose and blew hard during the third night, but the dory shipped little water. To keep awake and warm he hooked his arms around a thwart and rocked back and forth, back and forth. The night was long, and Tom was poor company.

At dawn of the fourth day, Sunday, he hauled in the drag and bent again to the oars. The night wind had expired. The sea was calm, and the cold was not so sharp. What he had taken to be a massive rock the previous evening turned out to be an island, cloaked with snow.

He rested on the oars and inspected it. There were no signs of life, neither harbor nor house. He concluded it was barren, and since it lay away from where he presumed the mainland to be, he oared on by.

All morning he rowed and in the early afternoon passed a cluster of rocks jutting out of the sea. All afternoon he rowed in a sort of perpetual motion easier to maintain than stop. Now and then he glanced over his shoulder without breaking the clockwork of his body and the oars.

Late in the afternoon a white stretch of coast rose thinly out of the horizon.

He rowed on.

At the edge of dusk the dory moved into a strong tide rip. The ocean was black and turbulent from the seaward surge of a brackish current, out and over the incoming tide. He figured he was outside the mouth of a rapidly emptying river. The boat was buffeted by the maelstrom of opposing waters, and he struggled on. Now he could see the outline of the narrow entrance. Sheer rock portals overhung with snow climbed a quarter of a mile out of the banging surf.

At dusk the wind arose, and the sea erupted into whitecaps. Every stroke an agony, he fought the current and crawled through the narrows. The bluffs towered over him. He dared not miss even a stroke lest the river disgorge him back to the sea.

Searching the snow-laden banks in the last glimmer of twilight as he rowed, his eyes stopped at a broken wharf with a shed on it. Beyond, on the shore, was a hut, steeped in snow, silent and deserted.

His thirst rushed in on him.

I could tell by the color of the water running out that fresh water could be found if I could only row up the river against the tide, and at that time I would give ten years of my life for a drink of water. I rowed some distance up the river, when all at once my mind gave way. I seemed to think that some former shipmates was laughing at the little headway I was making.

Abruptly, he turned back and rowed for the wharf and the lifeless hut.

The moon had risen, and by its frigid light he worked up to the landing. Next to it the waves were breaking against a flat rock. He guided the dory alongside, shipped the oars and stood up. His hips and knees crackled, and he nearly fell as he stepped out. He hooked an arm through the becket, pulled the boat partway onto the rock and hove the drag over the wharf. Then he clambered up himself.

The deadness in his feet told him they were frozen.

He stumbled into the shed and found a barrel half full of salt codfish. Sure that if he ate some now the salt would drive him crazy, he broke through the ice on top and buried a couple in the snow, hoping it would draw out the salt and freshen them by morning. The thought of the fish in the dory never crossed his mind.

He waded through the snow to the hut and pushed in the rotten door. The roof was patched with sky, and the snow on the dirt floor came up to his knees. There was a table in one room, a bedstead in the other, both drifted with snow.

As he turned back to the doorway, his eyes wandered toward the river narrows and out beyond to the ocean. There, in the frame of the cliffs, a silhouette against the moonlit sea, was a schooner passing to the east. It had not been in view when he entered the river, and he thought it must be making for a harbor not far away. He resolved to spend the night in the shack and at daybreak to get back in the dory, row out of the river and search for life to the eastward.

He clawed the boards from the bed, brushed away the snow and turned them over for something dry to lie on. In a corner he found some fishlines rolled up on reels. A torn net hung from a beam. He put the lines and reels at the head of the bed for a pillow, lay down and drew the net over his body.

The cold pierced him. He shivered so, he thought his teeth would break, and every muscle in his body joined the uncontrollable contagion of his shaking. The cold, the stillness, the total fatigue were a curtain closing around his consciousness. His very eyelids begged for rest. But he knew that if he slept he would not wake.

Pushing the net away, he dragged himself from the boards and walked the drifted floor, eating snow from the table; the more he ate, the more he craved. All that fourth night he walked the floor and ate the snow, and his thirst was merciless.

The earliest light of the fifth day brought him outside. He floundered through the drifts back to the wharf. The night wind had moderated, but before it fell off it had pushed the sea up into the river and against the shore.

The dory was awash with water. Tom was a weird shape in the bottom. The thwarts and the oars revolved in an eddy under the wharf.

The waves had pounded the boat against the rock, knocking the plug from the drainhole, and the water had poured up through. One plank below the port waterline was splintered; another, under the gunwale, was smashed.

Copyright © 2000 by Simon & Schuster

Recenzii

Brings alive the struggles of the Gloucester men at seas in the era of fishing under sail like no other book I've ever read....A wonderful, beautifully written book.

The only name I can think of that is more Gloucester than Howard Blackburn is Joe Garland. This is the great New England fishing legend definitively told.

One of the most remarkable feats of survival in the history of seafaring....It is one for all whose interest runs to the never-ending conflict between man and the sea.

Howard Blackburn is legendary even today among North Atlantic fishermen, and Joe Garland's lyrical book reveals the even more astonishing man behind the legend. A terrific read: brisk, poetic, and full of the sea.

The only name I can think of that is more Gloucester than Howard Blackburn is Joe Garland. This is the great New England fishing legend definitively told.

One of the most remarkable feats of survival in the history of seafaring....It is one for all whose interest runs to the never-ending conflict between man and the sea.

Howard Blackburn is legendary even today among North Atlantic fishermen, and Joe Garland's lyrical book reveals the even more astonishing man behind the legend. A terrific read: brisk, poetic, and full of the sea.

Descriere

"Joe Garland has done a magnificent job telling not only the story of Gloucester's most famous son, but also the story of the fishing industry in its hey day. A wonderful, beautifully written book". SEBASTIAN JUNGER, author of THE PERFECT STORM