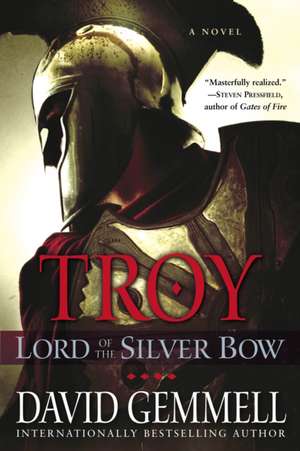

Lord of the Silver Bow: Troy Trilogy

Autor David Gemmellen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 sep 2006 – vârsta de la 14 până la 18 ani

Argurios the Mykene is a peerless fighter, a man of unbending principles and unbreakable will. Like all of the Mykene warriors, he lives to conquer and to kill. Dispatched by King Agamemnon to scout the defenses of the golden city of Troy, he is Helikaon’s sworn enemy.

Andromache is a priestess of Thera betrothed against her will to Hektor, prince of Troy. Scornful of tradition, skilled in the arts of war, and passionate in the ways of her order, Andromache vows to love whom she pleases and to live as she desires.

Now fate is about to thrust these three together–and, from the sparks of passionate love and hate, ignite a fire that will engulf the world.

Readers who know the works of David Gemmell expect nothing less than excellence from this author, whose taut prose, driving plots, and full-bodied characters have won him legions of fans the world over. Now, with this first masterly volume in an epic reimagining of the Trojan War, Gemmell has written an ageless drama of brave deeds and fierce battles, of honor and treachery, of love won and lost.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 126.98 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 190

Preț estimativ în valută:

24.30€ • 25.37$ • 20.11£

24.30€ • 25.37$ • 20.11£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 14-28 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780345494573

ISBN-10: 0345494571

Pagini: 476

Dimensiuni: 140 x 210 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.57 kg

Editura: BALLANTINE BOOKS

Seria Troy Trilogy

ISBN-10: 0345494571

Pagini: 476

Dimensiuni: 140 x 210 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.57 kg

Editura: BALLANTINE BOOKS

Seria Troy Trilogy

Notă biografică

David Gemmell was born in London, England, in the summer of 1948. Expelled from school at sixteen, he became a bouncer, working nightclubs in Soho. Born with a silver tongue, Gemmell rarely needed to bounce customers, relying instead on his gift of gab to talk his way out of trouble. This talent eventually led him to jobs as a freelancer for the London Daily Mail, the Daily Mirror, and the Daily Express. His first novel, Legend, was published in 1984 and has remained in print ever since. He became a full-time writer in 1986. His books consistently top the London Times bestseller list.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

The Cave of Wings

The twelve men in ankle-length cloaks of black wool stood silently at the cave mouth. They did not speak or move. The early autumn wind was unnaturally chilly, but they did not blow warm air on cold hands. Moonlight shimmered on their bronze breastplates and white-crested helmets, on their embossed wrist guards and greaves, and on the hilts of the short swords scabbarded at their waists. Yet despite the presence of cold metal against their bodies they did not shiver.

The night grew colder, and it began to rain as midnight approached. Hail fell and clattered against their armor, and still they did not move.

Then there came another warrior, tall and stooping, his cloak flapping in the fierce wind. He, too, was armored, though his cuirass was inlaid with gold and silver, as were the helmet and greaves he wore.

“Is he inside?” he asked, his voice deep.

“Yes, my king,” answered one of the men, tall and broad- shouldered, with deep-set gray eyes. “He will summon us when the gods speak.”

“Then we wait,” replied Agamemnon.

The rain eased, and the king’s dark eyes scanned his Followers. Then he looked into the Cave of Wings. Deep within he could see firelight flickering on the craggy walls and even from there smell the acrid and intoxicating fumes from the prophecy flames. As he watched, the fire dimmed.

Unused to waiting, he felt his anger rise but masked it. Even a king was expected to be humble in the presence of the gods.

Every four years the king of Mykene and twelve of his most trusted Followers were expected to hear the words of the gods. The last time Agamemnon had stood there, he had just interred his father and his own reign was about to begin. He had been nervous then but was more so now, for the prophecies he had heard that first time had come true. He had become infinitely richer. His wife had borne him three healthy children, though all were girls. The armies of Mykene had been victorious in every battle, and a great hero had fallen.

But Agamemnon also recalled the journey his father had made to the Cave of Wings eight years previously and his ashen face on his return. He would not speak of the final prophecy, but one of the Followers told it to his wife, and the word spread. The seer had concluded with the words: “Farewell, Atreus King. You will not walk the Cave of Wings again.”

The great battle king had died one week before the next summoning.

A woman dressed all in black emerged from the cave. Even her head was covered by a veil of gauze. She did not speak but raised her hand, beckoning the waiting men. Agamemnon took a deep breath and led the group inside.

The entrance was narrow, and they removed their crested helmets and followed the woman in single file until at last they reached the remains of the prophecy fire. Smoke still hung in the air, and as he breathed, Agamemnon felt his heart beating faster. Colors became brighter, and small sounds—the creaking of leather, the shifting of sandaled feet on stone—were louder, almost threatening.

The ritual was hundreds of years old, based on an ancient belief that only on the point of death could a priest commune fully with the gods, and so every four years a man was chosen to die for the sake of the king.

Keeping his breathing shallow, Agamemnon looked down at the slender old man lying on a pallet bed. His face was pale in the firelight, his eyes wide and staring. The hemlock paralysis had begun. He would be dead within moments.

Agamemnon waited.

“Fire in the sky,” said the priest, “and a mountain of water touching the clouds. Beware the great horse, Agamemnon King.” The old man sagged back, and the woman in black knelt by him, lifting and supporting his frail body.

“Offer me no riddles,” Agamemnon said. “What of the kingdom? What of the might of the Mykene?”

The priest’s eyes blazed briefly, and Agamemnon saw anger there. Then it passed, and the old man smiled. “Your will prevails here, King. I would have offered you a forest of truth, but you wish to speak of a single leaf. Very well. Mighty still will you be when next you walk this corridor of stone. Father to a son.” He whispered something to the woman, who held a cup of water to his lips.

“And what dangers will I face?” Agamemnon asked.

The old priest’s body spasmed, and he cried out. Then he relaxed and stared up at the king. “A ruler is always in peril, Agamemnon King. Unless he be strong, he will be torn down. Unless he be wise, he will be overthrown. The seeds of doom are planted in every season and need neither sun nor rain to make them grow. You sent a hero to end a small threat, and thus you planted the seeds. Now they grow, and swords will spring from the earth.”

“You speak of Alektruon. He was my friend.”

“He was no man’s friend! He was a slaughterer and did not heed the warnings. He trusted in his cunning, his cruelty, and his might. Poor blind Alektruon. Now he knows the magnitude of his error. Arrogance laid him low, for no man is invincible. Those the gods would destroy they first make proud.”

“What more have you seen?” said Agamemnon. “Speak now! Death is upon you.”

“I have no fear of death, King of Swords, King of Blood, King of Plunder. Nor should you. You will live forever, Agamemnon, in the hearts and minds of men. When your father’s name has fallen to dust and whispered away on the winds of time, yours will be spoken loud and often. When your line is a memory and all kingdoms have come to ashes, still your name will echo. This I have seen.”

“This is more to my liking,” said the king. “What else? Be swift now, for your time is short. Give a name to the greatest danger I will face.”

“You desire but a name? How . . . strange men are. You could have . . . asked for answers, Agamemnon.” The old man’s voice was fading and slurring. The hemlock was reaching his brain.

“Give me a name and I will know the answer.”

Another flash of anger lit the old man’s eyes, holding back the advancing poison. When he spoke, his voice was stronger. “Alektruon asked me for a name when I was but a seer and not blessed—as now—with the wisdom of the dying. I named Helikaon, the Golden One. And what did he do . . . this foolish man? He sailed the seas in search of Helikaon and brought his doom upon himself. Now you seek a name, Agamemnon King. It is the same name: Helikaon.” The old priest closed his eyes. The silence grew.

“Helikaon threatens me?” the king asked.

The dying priest spoke again. “I see men burning like candles, and . . . a ship of flame. I see a headless man . . . and a great fury. I see . . . I see many ships, like a great flock of birds. I see war, Agamemnon, long and terrible, and the deaths of many heroes.” With a shuddering cry he fell back into the arms of the veiled woman.

“Is he dead?” Agamemnon asked.

The woman felt for a pulse and then nodded. Agamemnon swore.

A powerful warrior moved alongside him, his hair so blond that it appeared white in the lamplight. “He spoke of a great horse, lord. The sails of Helikaon’s ships are all painted with the symbol of a rearing black horse.”

Agamemnon remained silent. Helikaon was kin to Priam, the king of Troy, and Agamemnon had a treaty of alliance with Troy and with most of the trading kingdoms on the eastern coast. While maintaining those treaties he also financed pirate raids by Mykene galleys, looting the towns of his allies and capturing trade ships and cargoes of copper, tin, lead, alabaster, and gold. Each one of the galleys tithed him its takings. The plunder allowed him to equip his armies and bestow favors on his generals and soldiers. Publicly, though, he denounced the pirates and threatened them with death, and so he could not openly declare Helikaon an enemy of Mykene. Troy was a rich and powerful kingdom, and that trade alone brought in large profits, paid in copper and tin, without which bronze armor and weapons could not be made.

War with the Trojans was coming, but he was not ready to make an enemy of their king.

The fumes from the prophecy fire were less noxious now, and Agamemnon felt his head clearing. The priest’s words had been massively reassuring. He would have a son, and the name of Agamemnon would echo through the ages.

Yet the old man also had spoken about seeds of doom, and he could not ignore the warning.

He looked the blond man in the eye. “Let it be known, Kolanos, that twice a man’s weight in gold awaits whoever kills Helikaon.”

“Every pirate ship on the Great Green will hunt him down for such a reward,” said Kolanos. “By your leave, my king, I will also take my three galleys in search of him. However, it will not be easy to draw him out. He is a cunning fighter and cool in battle.”

“Then you will make him less cool, my breaker of spirits,” said Agamemnon. “Find those Helikaon loves and kill them. He has family in Dardanos, a young brother he dotes on. Begin with him. Let Helikaon know rage and despair. Then rip his life from him.”

“I shall leave tomorrow, lord.”

“Attack him on the open sea, Kolanos. If you find him on land and the opportunity arises, have him stabbed, or throttled, or poisoned—I care not. But the trail of his death must not end at my hall. At sea do as you will. If you take him alive, saw the head from his shoulders—slowly. Ashore, make his death swift and quiet. A private quarrel. You understand me?”

“I do, my king.”

“When last I heard, Helikaon was in Kypros,” said Agamemnon, “overseeing the building of a great ship. I am told it will be ready to sail by season’s end. Time enough for you to light a fire under his soul.”

There was a strangled cry from behind them. Agamemnon swung around. The old priest had opened his eyes again. His upper body was trembling, his arms jerking spasmodically.

“The age of heroes is passing!” he shouted, his voice suddenly clear and strong. “The rivers are all of blood, the sky aflame! And look how men burn upon the Great Green!” His dying eyes fixed on Agamemnon’s face. “The Horse! Beware the Great Horse!” Blood spurted from his mouth, drenching his pale robes. His face contorted, his eyes wide with panic. Then another spasm shook him, and a last breath rattled from his throat.

From the Hardcover edition.

The twelve men in ankle-length cloaks of black wool stood silently at the cave mouth. They did not speak or move. The early autumn wind was unnaturally chilly, but they did not blow warm air on cold hands. Moonlight shimmered on their bronze breastplates and white-crested helmets, on their embossed wrist guards and greaves, and on the hilts of the short swords scabbarded at their waists. Yet despite the presence of cold metal against their bodies they did not shiver.

The night grew colder, and it began to rain as midnight approached. Hail fell and clattered against their armor, and still they did not move.

Then there came another warrior, tall and stooping, his cloak flapping in the fierce wind. He, too, was armored, though his cuirass was inlaid with gold and silver, as were the helmet and greaves he wore.

“Is he inside?” he asked, his voice deep.

“Yes, my king,” answered one of the men, tall and broad- shouldered, with deep-set gray eyes. “He will summon us when the gods speak.”

“Then we wait,” replied Agamemnon.

The rain eased, and the king’s dark eyes scanned his Followers. Then he looked into the Cave of Wings. Deep within he could see firelight flickering on the craggy walls and even from there smell the acrid and intoxicating fumes from the prophecy flames. As he watched, the fire dimmed.

Unused to waiting, he felt his anger rise but masked it. Even a king was expected to be humble in the presence of the gods.

Every four years the king of Mykene and twelve of his most trusted Followers were expected to hear the words of the gods. The last time Agamemnon had stood there, he had just interred his father and his own reign was about to begin. He had been nervous then but was more so now, for the prophecies he had heard that first time had come true. He had become infinitely richer. His wife had borne him three healthy children, though all were girls. The armies of Mykene had been victorious in every battle, and a great hero had fallen.

But Agamemnon also recalled the journey his father had made to the Cave of Wings eight years previously and his ashen face on his return. He would not speak of the final prophecy, but one of the Followers told it to his wife, and the word spread. The seer had concluded with the words: “Farewell, Atreus King. You will not walk the Cave of Wings again.”

The great battle king had died one week before the next summoning.

A woman dressed all in black emerged from the cave. Even her head was covered by a veil of gauze. She did not speak but raised her hand, beckoning the waiting men. Agamemnon took a deep breath and led the group inside.

The entrance was narrow, and they removed their crested helmets and followed the woman in single file until at last they reached the remains of the prophecy fire. Smoke still hung in the air, and as he breathed, Agamemnon felt his heart beating faster. Colors became brighter, and small sounds—the creaking of leather, the shifting of sandaled feet on stone—were louder, almost threatening.

The ritual was hundreds of years old, based on an ancient belief that only on the point of death could a priest commune fully with the gods, and so every four years a man was chosen to die for the sake of the king.

Keeping his breathing shallow, Agamemnon looked down at the slender old man lying on a pallet bed. His face was pale in the firelight, his eyes wide and staring. The hemlock paralysis had begun. He would be dead within moments.

Agamemnon waited.

“Fire in the sky,” said the priest, “and a mountain of water touching the clouds. Beware the great horse, Agamemnon King.” The old man sagged back, and the woman in black knelt by him, lifting and supporting his frail body.

“Offer me no riddles,” Agamemnon said. “What of the kingdom? What of the might of the Mykene?”

The priest’s eyes blazed briefly, and Agamemnon saw anger there. Then it passed, and the old man smiled. “Your will prevails here, King. I would have offered you a forest of truth, but you wish to speak of a single leaf. Very well. Mighty still will you be when next you walk this corridor of stone. Father to a son.” He whispered something to the woman, who held a cup of water to his lips.

“And what dangers will I face?” Agamemnon asked.

The old priest’s body spasmed, and he cried out. Then he relaxed and stared up at the king. “A ruler is always in peril, Agamemnon King. Unless he be strong, he will be torn down. Unless he be wise, he will be overthrown. The seeds of doom are planted in every season and need neither sun nor rain to make them grow. You sent a hero to end a small threat, and thus you planted the seeds. Now they grow, and swords will spring from the earth.”

“You speak of Alektruon. He was my friend.”

“He was no man’s friend! He was a slaughterer and did not heed the warnings. He trusted in his cunning, his cruelty, and his might. Poor blind Alektruon. Now he knows the magnitude of his error. Arrogance laid him low, for no man is invincible. Those the gods would destroy they first make proud.”

“What more have you seen?” said Agamemnon. “Speak now! Death is upon you.”

“I have no fear of death, King of Swords, King of Blood, King of Plunder. Nor should you. You will live forever, Agamemnon, in the hearts and minds of men. When your father’s name has fallen to dust and whispered away on the winds of time, yours will be spoken loud and often. When your line is a memory and all kingdoms have come to ashes, still your name will echo. This I have seen.”

“This is more to my liking,” said the king. “What else? Be swift now, for your time is short. Give a name to the greatest danger I will face.”

“You desire but a name? How . . . strange men are. You could have . . . asked for answers, Agamemnon.” The old man’s voice was fading and slurring. The hemlock was reaching his brain.

“Give me a name and I will know the answer.”

Another flash of anger lit the old man’s eyes, holding back the advancing poison. When he spoke, his voice was stronger. “Alektruon asked me for a name when I was but a seer and not blessed—as now—with the wisdom of the dying. I named Helikaon, the Golden One. And what did he do . . . this foolish man? He sailed the seas in search of Helikaon and brought his doom upon himself. Now you seek a name, Agamemnon King. It is the same name: Helikaon.” The old priest closed his eyes. The silence grew.

“Helikaon threatens me?” the king asked.

The dying priest spoke again. “I see men burning like candles, and . . . a ship of flame. I see a headless man . . . and a great fury. I see . . . I see many ships, like a great flock of birds. I see war, Agamemnon, long and terrible, and the deaths of many heroes.” With a shuddering cry he fell back into the arms of the veiled woman.

“Is he dead?” Agamemnon asked.

The woman felt for a pulse and then nodded. Agamemnon swore.

A powerful warrior moved alongside him, his hair so blond that it appeared white in the lamplight. “He spoke of a great horse, lord. The sails of Helikaon’s ships are all painted with the symbol of a rearing black horse.”

Agamemnon remained silent. Helikaon was kin to Priam, the king of Troy, and Agamemnon had a treaty of alliance with Troy and with most of the trading kingdoms on the eastern coast. While maintaining those treaties he also financed pirate raids by Mykene galleys, looting the towns of his allies and capturing trade ships and cargoes of copper, tin, lead, alabaster, and gold. Each one of the galleys tithed him its takings. The plunder allowed him to equip his armies and bestow favors on his generals and soldiers. Publicly, though, he denounced the pirates and threatened them with death, and so he could not openly declare Helikaon an enemy of Mykene. Troy was a rich and powerful kingdom, and that trade alone brought in large profits, paid in copper and tin, without which bronze armor and weapons could not be made.

War with the Trojans was coming, but he was not ready to make an enemy of their king.

The fumes from the prophecy fire were less noxious now, and Agamemnon felt his head clearing. The priest’s words had been massively reassuring. He would have a son, and the name of Agamemnon would echo through the ages.

Yet the old man also had spoken about seeds of doom, and he could not ignore the warning.

He looked the blond man in the eye. “Let it be known, Kolanos, that twice a man’s weight in gold awaits whoever kills Helikaon.”

“Every pirate ship on the Great Green will hunt him down for such a reward,” said Kolanos. “By your leave, my king, I will also take my three galleys in search of him. However, it will not be easy to draw him out. He is a cunning fighter and cool in battle.”

“Then you will make him less cool, my breaker of spirits,” said Agamemnon. “Find those Helikaon loves and kill them. He has family in Dardanos, a young brother he dotes on. Begin with him. Let Helikaon know rage and despair. Then rip his life from him.”

“I shall leave tomorrow, lord.”

“Attack him on the open sea, Kolanos. If you find him on land and the opportunity arises, have him stabbed, or throttled, or poisoned—I care not. But the trail of his death must not end at my hall. At sea do as you will. If you take him alive, saw the head from his shoulders—slowly. Ashore, make his death swift and quiet. A private quarrel. You understand me?”

“I do, my king.”

“When last I heard, Helikaon was in Kypros,” said Agamemnon, “overseeing the building of a great ship. I am told it will be ready to sail by season’s end. Time enough for you to light a fire under his soul.”

There was a strangled cry from behind them. Agamemnon swung around. The old priest had opened his eyes again. His upper body was trembling, his arms jerking spasmodically.

“The age of heroes is passing!” he shouted, his voice suddenly clear and strong. “The rivers are all of blood, the sky aflame! And look how men burn upon the Great Green!” His dying eyes fixed on Agamemnon’s face. “The Horse! Beware the Great Horse!” Blood spurted from his mouth, drenching his pale robes. His face contorted, his eyes wide with panic. Then another spasm shook him, and a last breath rattled from his throat.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

Advance praise for Troy: Lord of the Silver Bow

“This is how the oldest tales should be read and known. This is the grand style of storytelling. Gemmell is a master of plot, but his triumph is creating men and women so real that their trials are agony and their triumph is glorious.”

–Conn Iggulden, author of the Emperor series

“I can say of David Gemmell, that he's the only writer of historical fiction or heroic fantasy whose prose I actually study, line by line, trying to decode how he produces the effects that he does. Hail to Lord of the Silver Bow! Bravo, Mr. Gemmell!”

–Steven Pressfield, author of Gates of Fire and The Virtues of War

Praise for David Gemmell

“I love David Gemmell’s work. He’s one of the best out there today, and one of the reasons that fantasy is alive and well.”

–R. A. Salvatore

“Passionate, cleanly written prose, imaginative plots, and, above all, terrific storytelling.”

–Time Out London

“Gemmell not only knows how to tell a story, he knows how to tell a story you want to hear. He does high adventure as it ought to be done.”

–Greg Keyes

“Clean, swift action and a rich undercurrent of human understanding support Gemmell’s characters at each turn of the tale.”

–Kirkus Reviews

From the Hardcover edition.

“This is how the oldest tales should be read and known. This is the grand style of storytelling. Gemmell is a master of plot, but his triumph is creating men and women so real that their trials are agony and their triumph is glorious.”

–Conn Iggulden, author of the Emperor series

“I can say of David Gemmell, that he's the only writer of historical fiction or heroic fantasy whose prose I actually study, line by line, trying to decode how he produces the effects that he does. Hail to Lord of the Silver Bow! Bravo, Mr. Gemmell!”

–Steven Pressfield, author of Gates of Fire and The Virtues of War

Praise for David Gemmell

“I love David Gemmell’s work. He’s one of the best out there today, and one of the reasons that fantasy is alive and well.”

–R. A. Salvatore

“Passionate, cleanly written prose, imaginative plots, and, above all, terrific storytelling.”

–Time Out London

“Gemmell not only knows how to tell a story, he knows how to tell a story you want to hear. He does high adventure as it ought to be done.”

–Greg Keyes

“Clean, swift action and a rich undercurrent of human understanding support Gemmell’s characters at each turn of the tale.”

–Kirkus Reviews

From the Hardcover edition.