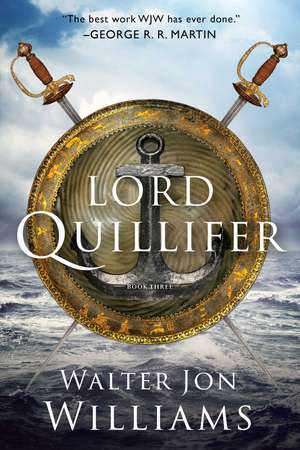

Lord Quillifer: Quillifer

Autor Walter Jon Williamsen Limba Engleză Paperback – 25 mai 2022

“Chock full of derring-do, blood and thunder, swashbuckling, and other good stuff.” —Paul di Filippo, Locus

“You have risen as far as you can, and from this point, you may only fall. The matter is inevitable, and I need not intervene.”

Quillifer’s archenemy, the beautiful and vengeful goddess Orlanda, predicts his inescapable fall from power, and Quillifer has to admit that she may be right.

Quillifer has risen high at court. The butcher’s son is now a lord, and now is the confidential agent of the state, the caretaker of the kingdom’s secrets, and the secret lover of the young and brilliant Queen Floria.

He finds himself surrounded by perils. The nobles are at odds with one another, but united in despising Quillifer. Someone has brought deadly poison into court, and Quillifer fears the Queen may be the intended victim. Another assassination plot is aimed at Quillifer himself, and an enemy nation has landed troops intending to topple Floria by force. Quillifer must solve every mystery, meet every danger, and discover every secret in order to guard himself and his love, Floria, from the dangers that beset them.

Lord Quillifer marks the anticipated return of Walter Jon Williams, a New York Times bestselling author and multiple award-winning fantasy author.

Preț: 111.72 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 168

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.38€ • 22.09$ • 17.79£

21.38€ • 22.09$ • 17.79£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 04-18 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781481490030

ISBN-10: 1481490036

Pagini: 528

Ilustrații: f-c jacket

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 36 mm

Greutate: 0.48 kg

Editura: S&S/Saga Press

Colecția S&S/Saga Press

Seria Quillifer

ISBN-10: 1481490036

Pagini: 528

Ilustrații: f-c jacket

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 36 mm

Greutate: 0.48 kg

Editura: S&S/Saga Press

Colecția S&S/Saga Press

Seria Quillifer

Notă biografică

Walter Jon Williams is the author of thirty volumes of fiction, in addition to works in film, television, comics, and the gaming field. Williams has appeared on the bestseller lists of The Times and The New York Times. He is a world traveler, scuba diver, and a black belt in Kenpo Karate. He has twice been awarded the Nebula Award.

Extras

Chapter OneCHAPTER ONE

You rested your cheek upon your palm as you sat at the table, your expression a mixture of disdain and weariness. “I have been traveling this world of yours, Quillifer,” you said, “and I find it a dreary place, where the debased inhabitants employ themselves only in making it drearier.” Contempt laced your words. “What have your cannons and galleons, your astrolabes and hairsprings brought you but fruitless and thoughtless activity? And your printing presses serve only to better distribute to the world your own sad ignorance.”

“Our ignorance is hardly our fault,” I pointed out. “And you could lessen that ignorance, were you so inclined. For you were created with the world and know many of its secrets. How much could you contribute to our metaphysics, our history, our natural philosophy?”

You waved a scornful hand. “You think me as old as the world? Nay—my kind grew up alongside yours, and in the early days we dreamed together, and we built together. But my people learned wisdom, and yours never did.” You laughed. “Over many centuries I tried to improve you,” you said, “but you remain obstinate in your foolishness, and now I find your whole race irredeemable. Why should I take up that useless task again, when I find you all unchanged, and as witless and savage as the first human to come blinking from the shadows of the forest into the dazzling light of the sun?”

I reached for my crystal goblet and held it glittering in the light of the candle, bubbles rising like worlds in the golden wine. “I think you need an occupation,” said I.

Mischief glittered in your green eyes. “Besides tormenting you, Quillifer?”

“Surely that grows as tedious as the rest of your dealings with humanity,” I said.

“You have not yet ceased to amuse,” you said. “Your wrigglings, your plottings, your absurd ambitions.” I sensed a shift in your mood, as if a tide had changed behind those sea-green eyes. “Yet perhaps I will cease my plots for a time. They are hardly necessary now.”

“I would be very pleased should you no longer seek my downfall,” said I, “but how is your intervention no longer necessary?”

Your forest-green satins rustled as you took the wine-cup from my hand and drained it. “A second-rate vintage at best,” you said.

“I think you are evading my question.”

You lifted your cheek from your hand in order to better regard me. You tossed your head, and your red hair blossomed briefly beneath its circlet of gold, then fell back into place. Your mossy scent wafted through the night. “Consider your position now, Quillifer,” you said. “You live at court, where every jest is malicious, scandal lurks behind every tapestry, the very air breathes conspiracy, and a dagger is concealed behind every smile.”

“Indeed,” said I, “the court at times resembles a congress of fishwives, only less well-mannered.”

“Fishwives are less inclined to poison and murder.” A corner of your mouth turned up in a smile. “Whereas you, Quillifer, are at your zenith. You are the favorite of the Queen as well as her secret lover. You are a Knight of the Red Horse and the new-made Count of Selford, which is a title formerly employed only by members of the royal family. You sit on the Privy Council, and even the hoariest statesman or the most regal duke is obliged to reckon with you. Do you think they love you for it?” Again you laugh. “Every courtier hates you and wants to be your friend, and those to whom you offer favors grudge the thanks they offer you.”

I contemplate my empty goblet. “You think I don’t know it?”

“I think you believe that none of that matters, so long as you have the love of the Queen.”

“And does it?” I decanted more wine into the cup.

“I think you may not live in a world of whispers and enmity without suffering some loss,” you said. “And in your position, to suffer any loss is to lose all, for once you are shown to be vulnerable, your very friends will become wolves and tear out your throat. You have risen as far as you can, and from this point you may only fall.” You held up a hand. “The matter is inevitable, and I need not intervene.”

“Oh,” said I, offhand, “your premise may be somewhat in error. I may rise farther still.”

Your barking laugh was incredulous. “What—you think you can marry the Queen?”

“It matters not what I think,” said I, “it matters what the Queen thinks.”

I sipped the wine. It was a second-rate vintage, but then, I had got it from the palace butler, who was probably trying to put me in my place.

“If the Queen marries a butcher’s son,” you said, “she would lose her authority faster than if she had run naked after hares armed with a pruning-hook.”

“You offer a striking image,” I said. “Have you met many monarchs who pursued game in such a manner?”

“One,” you said, “and she was not a monarch for long.”

Again I sipped the wine. “There remains the question,” I said, “as to whether I am a butcher’s son or the Count of Selford.”

“The nobility think they know the answer to that question,” you said. “And it is not an answer that would please you.”

“I care not if they please me,” said I, “so long as they hold by the Queen.”

“The Queen has a government,” you said, “and those not in power will form an opposition. But do they oppose the Queen’s government, or the Queen herself? At some point these boundaries become indistinct.”

“There is no alternative to Her Majesty,” said I, “but submission to a foreign power. Even those opposed to her choices will hold by her.”

“And they will hold by her,” you said, “so long as she doesn’t do something as mad as to marry you.”

“I’m sure the Queen knows best.” Though I admit that your certainty made me uneasy.

I had sent Master Redbine, a retired member of the College of Heralds, to my home city of Ethlebight to pursue inquiries about my ancestors, in hopes of finding a vine of nobility, however slender, wrapped about my family tree. If I could convincingly offer a noble ancestor—preferably from an otherwise extinct house—then I might ease the resentment of my supposed peers.

I was not entirely proud of this stratagem, for I had no wish to debase myself by making some false claim of nobility in order to gratify the prejudices of some well-bred, fleering coxcomb; but insofar as it might keep the peace in Her Majesty’s council, I would make the attempt.

And of course half the nobility based their pretensions on invented genealogies, so I would find myself in the very best company.

You looked at me with your emerald eyes. “Your lover comes,” you said. “And though I despise all your women, I think I despise Floria the least.” Your lips turn up in a self-satisfied smile. “Perhaps,” you add, “because you will not keep her long.”

And then you were gone, and I turned to the secret, silent door through which Her Majesty soon emerged.

Floria wore a dressing gown of royal red satin and matching high-heeled sandals with bows. Her ladies had bound her ill-tempered dark hair with a ribbon, but it was already escaping its bonds. She carried a candle in her hand, with which she had lighted her way down the secret passage to my room. The great white castle overlooking Selford has its share of such passages, through which Floria’s father used to visit his many mistresses.

Floria lifted her chin, and her nostrils flared as she tested the air. “What is that scent?” she asked.

“Labdanum, I think,” I said. “I had an otherworldly visitor.”

Her brows lifted in amusement. “Your fairy?”

“She isn’t a fairy, as I understand fairies,” said I. “A goddess, perhaps, and certainly a nymph, a nereid as proudly inconstant as her watery element.”

Floria walked across the room and drew the bar across the door. “This won’t keep out a goddess, I suppose,” she said, laughing, “but it will do well enough against sublunary invaders.”

I took the candle from her fingers and placed it on the fireplace mantel, pink marble carved with gloxinia and camellia, ornament suited to a monarch’s mistress. Floria’s bright galbanum scent flooded my senses, overwhelming your own earthy fragrance. Floria’s face was turned up to me, an opalescent shimmer in the dim light, and I kissed her lips. I lost count of time for a moment, and then Floria sighed and rested her head against my chest.

“I don’t know if I fully believe in this Orlanda of yours,” she said, “but I suspect any woman who visits you at this hour.”

“It is you I adore,” said I, “and it was the nymph I rejected, which accounts for her malignancy.”

Floria frowned. “Malignancy?”

“It’s a new word. I made it up.”

“Do we not already have good words for such a sentiment? ‘Mallecho,’ for example?”

“Would that make Orlanda a mallechist, then?”

As I attempt honesty whenever I think anyone might actually wish to hear the truth, I have told Floria about you, including the fact that you served her in the guise of the Aekoi Countess Marcella, who vanished when I unmasked you at the beginning of the rebellion against Viceroy Fosco. It seemed only just, that she should know she was the lover of a man cursed by a being extramundane, and that she should not be surprised by any extraordinary hostility directed against me.

She does not entirely believe me, I think, but is at least convinced that I believe in your existence.

“You need not fear her,” I told Floria, “for she has promised not to injure anyone I love, and I love you utterly.”

She looked up at me. “Yet you say she is inconstant. May she not retract that promise?”

“If she does, that will end her torment of me, her chief amusement in this world. For rather than risk one I love, I would make an end of myself immediately.” I smiled. “You begin to sound as if you believe in Orlanda.”

“Perhaps I do. Though I do not care to think that my safety is bought with such danger to you.”

I laughed. “Kiss me, love! For all her mischief has done is bring me to your arms.”

We kissed, and embraced, and went from there to other things, as you surely know if you were watching from some invisible perch. For I have noticed that, though you say that you hate and despise my lovers, you nevertheless maintain a great interest in them, and in our doings together.

It is almost as if you are jealous.

You rested your cheek upon your palm as you sat at the table, your expression a mixture of disdain and weariness. “I have been traveling this world of yours, Quillifer,” you said, “and I find it a dreary place, where the debased inhabitants employ themselves only in making it drearier.” Contempt laced your words. “What have your cannons and galleons, your astrolabes and hairsprings brought you but fruitless and thoughtless activity? And your printing presses serve only to better distribute to the world your own sad ignorance.”

“Our ignorance is hardly our fault,” I pointed out. “And you could lessen that ignorance, were you so inclined. For you were created with the world and know many of its secrets. How much could you contribute to our metaphysics, our history, our natural philosophy?”

You waved a scornful hand. “You think me as old as the world? Nay—my kind grew up alongside yours, and in the early days we dreamed together, and we built together. But my people learned wisdom, and yours never did.” You laughed. “Over many centuries I tried to improve you,” you said, “but you remain obstinate in your foolishness, and now I find your whole race irredeemable. Why should I take up that useless task again, when I find you all unchanged, and as witless and savage as the first human to come blinking from the shadows of the forest into the dazzling light of the sun?”

I reached for my crystal goblet and held it glittering in the light of the candle, bubbles rising like worlds in the golden wine. “I think you need an occupation,” said I.

Mischief glittered in your green eyes. “Besides tormenting you, Quillifer?”

“Surely that grows as tedious as the rest of your dealings with humanity,” I said.

“You have not yet ceased to amuse,” you said. “Your wrigglings, your plottings, your absurd ambitions.” I sensed a shift in your mood, as if a tide had changed behind those sea-green eyes. “Yet perhaps I will cease my plots for a time. They are hardly necessary now.”

“I would be very pleased should you no longer seek my downfall,” said I, “but how is your intervention no longer necessary?”

Your forest-green satins rustled as you took the wine-cup from my hand and drained it. “A second-rate vintage at best,” you said.

“I think you are evading my question.”

You lifted your cheek from your hand in order to better regard me. You tossed your head, and your red hair blossomed briefly beneath its circlet of gold, then fell back into place. Your mossy scent wafted through the night. “Consider your position now, Quillifer,” you said. “You live at court, where every jest is malicious, scandal lurks behind every tapestry, the very air breathes conspiracy, and a dagger is concealed behind every smile.”

“Indeed,” said I, “the court at times resembles a congress of fishwives, only less well-mannered.”

“Fishwives are less inclined to poison and murder.” A corner of your mouth turned up in a smile. “Whereas you, Quillifer, are at your zenith. You are the favorite of the Queen as well as her secret lover. You are a Knight of the Red Horse and the new-made Count of Selford, which is a title formerly employed only by members of the royal family. You sit on the Privy Council, and even the hoariest statesman or the most regal duke is obliged to reckon with you. Do you think they love you for it?” Again you laugh. “Every courtier hates you and wants to be your friend, and those to whom you offer favors grudge the thanks they offer you.”

I contemplate my empty goblet. “You think I don’t know it?”

“I think you believe that none of that matters, so long as you have the love of the Queen.”

“And does it?” I decanted more wine into the cup.

“I think you may not live in a world of whispers and enmity without suffering some loss,” you said. “And in your position, to suffer any loss is to lose all, for once you are shown to be vulnerable, your very friends will become wolves and tear out your throat. You have risen as far as you can, and from this point you may only fall.” You held up a hand. “The matter is inevitable, and I need not intervene.”

“Oh,” said I, offhand, “your premise may be somewhat in error. I may rise farther still.”

Your barking laugh was incredulous. “What—you think you can marry the Queen?”

“It matters not what I think,” said I, “it matters what the Queen thinks.”

I sipped the wine. It was a second-rate vintage, but then, I had got it from the palace butler, who was probably trying to put me in my place.

“If the Queen marries a butcher’s son,” you said, “she would lose her authority faster than if she had run naked after hares armed with a pruning-hook.”

“You offer a striking image,” I said. “Have you met many monarchs who pursued game in such a manner?”

“One,” you said, “and she was not a monarch for long.”

Again I sipped the wine. “There remains the question,” I said, “as to whether I am a butcher’s son or the Count of Selford.”

“The nobility think they know the answer to that question,” you said. “And it is not an answer that would please you.”

“I care not if they please me,” said I, “so long as they hold by the Queen.”

“The Queen has a government,” you said, “and those not in power will form an opposition. But do they oppose the Queen’s government, or the Queen herself? At some point these boundaries become indistinct.”

“There is no alternative to Her Majesty,” said I, “but submission to a foreign power. Even those opposed to her choices will hold by her.”

“And they will hold by her,” you said, “so long as she doesn’t do something as mad as to marry you.”

“I’m sure the Queen knows best.” Though I admit that your certainty made me uneasy.

I had sent Master Redbine, a retired member of the College of Heralds, to my home city of Ethlebight to pursue inquiries about my ancestors, in hopes of finding a vine of nobility, however slender, wrapped about my family tree. If I could convincingly offer a noble ancestor—preferably from an otherwise extinct house—then I might ease the resentment of my supposed peers.

I was not entirely proud of this stratagem, for I had no wish to debase myself by making some false claim of nobility in order to gratify the prejudices of some well-bred, fleering coxcomb; but insofar as it might keep the peace in Her Majesty’s council, I would make the attempt.

And of course half the nobility based their pretensions on invented genealogies, so I would find myself in the very best company.

You looked at me with your emerald eyes. “Your lover comes,” you said. “And though I despise all your women, I think I despise Floria the least.” Your lips turn up in a self-satisfied smile. “Perhaps,” you add, “because you will not keep her long.”

And then you were gone, and I turned to the secret, silent door through which Her Majesty soon emerged.

Floria wore a dressing gown of royal red satin and matching high-heeled sandals with bows. Her ladies had bound her ill-tempered dark hair with a ribbon, but it was already escaping its bonds. She carried a candle in her hand, with which she had lighted her way down the secret passage to my room. The great white castle overlooking Selford has its share of such passages, through which Floria’s father used to visit his many mistresses.

Floria lifted her chin, and her nostrils flared as she tested the air. “What is that scent?” she asked.

“Labdanum, I think,” I said. “I had an otherworldly visitor.”

Her brows lifted in amusement. “Your fairy?”

“She isn’t a fairy, as I understand fairies,” said I. “A goddess, perhaps, and certainly a nymph, a nereid as proudly inconstant as her watery element.”

Floria walked across the room and drew the bar across the door. “This won’t keep out a goddess, I suppose,” she said, laughing, “but it will do well enough against sublunary invaders.”

I took the candle from her fingers and placed it on the fireplace mantel, pink marble carved with gloxinia and camellia, ornament suited to a monarch’s mistress. Floria’s bright galbanum scent flooded my senses, overwhelming your own earthy fragrance. Floria’s face was turned up to me, an opalescent shimmer in the dim light, and I kissed her lips. I lost count of time for a moment, and then Floria sighed and rested her head against my chest.

“I don’t know if I fully believe in this Orlanda of yours,” she said, “but I suspect any woman who visits you at this hour.”

“It is you I adore,” said I, “and it was the nymph I rejected, which accounts for her malignancy.”

Floria frowned. “Malignancy?”

“It’s a new word. I made it up.”

“Do we not already have good words for such a sentiment? ‘Mallecho,’ for example?”

“Would that make Orlanda a mallechist, then?”

As I attempt honesty whenever I think anyone might actually wish to hear the truth, I have told Floria about you, including the fact that you served her in the guise of the Aekoi Countess Marcella, who vanished when I unmasked you at the beginning of the rebellion against Viceroy Fosco. It seemed only just, that she should know she was the lover of a man cursed by a being extramundane, and that she should not be surprised by any extraordinary hostility directed against me.

She does not entirely believe me, I think, but is at least convinced that I believe in your existence.

“You need not fear her,” I told Floria, “for she has promised not to injure anyone I love, and I love you utterly.”

She looked up at me. “Yet you say she is inconstant. May she not retract that promise?”

“If she does, that will end her torment of me, her chief amusement in this world. For rather than risk one I love, I would make an end of myself immediately.” I smiled. “You begin to sound as if you believe in Orlanda.”

“Perhaps I do. Though I do not care to think that my safety is bought with such danger to you.”

I laughed. “Kiss me, love! For all her mischief has done is bring me to your arms.”

We kissed, and embraced, and went from there to other things, as you surely know if you were watching from some invisible perch. For I have noticed that, though you say that you hate and despise my lovers, you nevertheless maintain a great interest in them, and in our doings together.

It is almost as if you are jealous.

Descriere

The Name of the Wind meets Sharpe in this “witty, colorful, exciting…exquisitely written” (George R. R. Martin) fantasy by Nebula Award–winning author Walter Jon Williams.