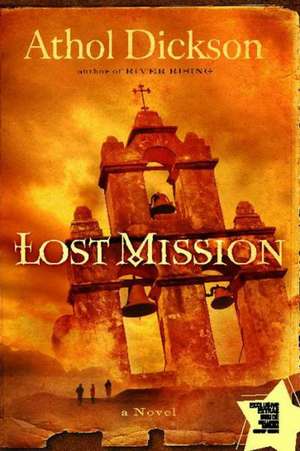

Lost Mission: A Novel

Autor Athol Dicksonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 14 sep 2009

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

An idyllic Spanish mission collapses atop the supernatural evidence of a shocking crime. Twelve generations later the ground is opened up, the forgotten ruins are disturbed, and rich and poor alike confront the onslaught of resurging hell on earth. Caught up in the catastrophe are . . .

- A humble shopkeeper compelled to leave her tiny village deep in Mexico to preach in America

- A minister wracked with guilt for loving the wrong woman

- An unimaginably wealthy man, blinded to the consequences of his grand plans

- A devoted father and husband driven to a horrible discovery that changes everything

Will the evil that destroyed the Misión de Santa Dolores rise to overwhelm them, or will they beat back the terrible desires that left the mission’s good Franciscan founder standing in the midst of flames ignited by his enemies and friends alike more than two centuries ago?

From the high Sierra Madres to the harsh Sonoran desert, from the privileged world of millionaire moguls to the impoverished immigrants who serve them, Athol Dickson once again weaves a gripping story of suspense that spans centuries and cultures to explore the abiding possibility of miracles.

Preț: 133.00 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 200

Preț estimativ în valută:

25.45€ • 26.47$ • 21.01£

25.45€ • 26.47$ • 21.01£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 22 martie-05 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781416583479

ISBN-10: 1416583475

Pagini: 368

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.37 kg

Editura: HOWARD PUB

Colecția Howard Books

Locul publicării:New York, NY

ISBN-10: 1416583475

Pagini: 368

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.37 kg

Editura: HOWARD PUB

Colecția Howard Books

Locul publicării:New York, NY

Extras

CAPÍTULO 1

EL DÍA DE LOS REYES, 6 DE ENERO DE 1767

LET US BEGIN THE STORY of La Misión de Santa Dolores on the holy day of the three kings, in Italy, in Assisi. To commemorate his twentieth year among the Franciscan brothers, Fray Alejandro Tapia Valdez made a pilgrimage to his beloved San Francisco’s humble chapel, the Porziuncola. For more than a week the friar prayed before the chapel’s frescoes, rarely ceasing for food or sleep. But despite his lengthy praises and petitions, despite his passionate devotion to Almighty God, Fray Alejandro was a pragmatic man. He did not believe the rumor, common in his day, that the frescoes’ perfection was beyond the ability of human hands. As we shall see, in time the friar would reconsider.

The Franciscan stood five feet four inches tall, an average Spaniard’s height in the eighteenth century. He was broad and unattractive. Heavy whiskers lurked beneath the surface of his jaw, darkly threatening to burst forth. Fray Alejandro’s brow was large and loomed above the recess of his eyes as if it were a cliff eroded by the pounding of the sea, ready to crash down at any moment. The black fullness of his hair had been shaved at the crown, leaving only a circular fringe around the edges of his head. His nose, once aquiline and proud, had become a perpetual reminder of the violence that had flattened it at some time in the past.

For all its ugliness, Fray Alejandro’s visage could not mask the gentleness within. His crooked smile shed warmth upon his fellow man. His hands were ever ready with a touch to reassure or steady, or to simply grant the gift of human presence. When someone spoke, be that person wise or not, he inclined his head and listened with his entire being, as if the speaker’s words had all the weight of holy writ. In his eyes was love.

Love does not defend against the sorrows of this world, of course. On the contrary, each day as Fray Alejandro knelt in prayer at the Porziuncola he became more deeply troubled. His imagination had recently been captured by strange stories of the heathen natives of the New World, isolated wretches with no knowledge of their Savior. This tragedy grew in Alejandro’s mind until he groaned aloud in sympathy for their unhappy souls. Other brothers kneeling on his left and right cast covert glances at him. Many thought his noisy prayers an uncouth intrusion, but caught up as he was in sacred agony, Alejandro did not notice.

Then came that holy day of the three kings, when in the midst of his entreaties for the pagans of New Spain, Fray Alejandro suddenly felt a painful heat as if his body were ablaze. In this, the first of his three burnings, Alejandro became faint. He heard a whisper saying, “Go and save my children.” The bells began to peal, although it was later said the ropes had not been touched. As startled pigeons burst forth from the bell tower, Alejandro rose.

How like the Holy Father to command such a journey on that day of days! Without a backward glance Fray Alejandro strode away from San Francisco’s little chapel as if following a star, determined to return at once to Hornachuelos, in Córdoba, there to seek permission from the abbot of the monastery of Santa María de los Ángeles for a voyage to New Spain.

The abbot’s assent was quickly given, but Fray Alejandro spent many months waiting on the vast bureaucracy of King Carlos III to approve his passage. Still, while the wheels of government turn slowly, slowly they do turn.

Finally, in late May of the year 1767, the good friar stood at the bulwarks of a galleon in the West Indian Fleet, tossed by the Atlantic, quite ill, and protected from the frigid spray by nothing but his robe of coarse handmade cloth. In spite of the pitching deck, always Alejandro faced New Spain, far beyond the horizon. His short, broad body seemed to strain against the wind and ocean waves with eagerness to be about his Father’s business.

But let us be more patient than the friar, for this is just the first of many journeys we shall follow as our story leads us back and forth through space and time. Indeed, the events Fray Alejandro has set in motion have their culmination far into the future. Therefore, leaving the Franciscan and his solitary ship, we cross many miles to reach a village known as Rincón de Dolores, high among the Sierra Madre mountains of Jalisco, Mexico. And we fly further still, centuries ahead of Alejandro, to find ourselves in these, our modern times.

Accompanied by norteño music blaring from loudspeakers and by much celebratory honking of automobile horns, we observe the burning of a makeshift structure of twigs and sticks and painted cardboard, which seemed a more substantial thing once it was engulfed, as if the busy flames were masons hard at work with red adobe. The people of the village of Rincón de Dolores were encouraged by the firmness of the fire. All the village cheered as the imitation barracks burned before them. They cheered, and with their jolly voices dared a pair of boys to stay in the inferno just a little longer.

There was much to enjoy on that Feast Day of Fray Alejandro—the floral garlands, the children in their antique costumes, the pinwheels spun by crackling fireworks, the somber procession of the saints along the avenida—but one citizen did not join the festivities.

Guadalupe Soledad Consuelo de la Garza trembled as she watched the flaming reenactment of the tragedy of La Misión de Santa Dolores. Who knew, but possibly this year the boys would stay too long within the flames? Who knew, but possibly this time the sticks would burn, the cardboard become ash and rise into the sky, and “Alejandro” and “the Indian” would not emerge? Spurred to foolishness by those who called for courage, might this be the year when merrymaking turned to mourning? The young woman with the long name—let us call her merely Lupe—feared it might be so, while the imitation barracks burned and the boys remained inside.

As was their ancient custom, after the fire was set by eager boys in Indian costumes, the village people chanted, “Muerte! Muerte! Muerte! Death to Spaniards! Death to traitors!” Their refrain arose in tandem with the flames. Only when the fire ascended to the middle of the mock barracks’ spindly walls did some within the crowd begin to yell, “Salid! Salid! Salid!” Come out! they called, a few of them at first, mostly girls and women, then as the minutes slowly passed this call became predominant, until the entire village shouted it as one, Come out! and the boys inside could flee the fire with honor.

Yet they did not come.

“Agua!” someone shouted, probably the boys’ parents, and nearby men with buckets hurried toward the crackling barracks walls. “Agua, rápido!” they shouted, and the first man swung his bucket back, prepared to douse a small part of the flames.

Such wild and forceful flames, and so little water, thought young Lupe. Holy Father, please protect them.

Even as she prayed, the first man thrust his bucket forward. Water sizzled in the burning sticks and rose as steam, and from the conflagration burst two little figures. One boy came out robed from head to foot in gray cloth, the cincture at his waist knotted in three places to bring poverty, obedience, and chastity to mind. He carried a bundle, the sacred retablo of Fray Alejandro concealed in crimson velvet, a small altarpiece which no one but Padre Hinojosa, the village priest, would ever see. The other boy came nearly naked with only a covering of sackcloth, his bare arms and legs agleam with aloe sap as protection from the heat. The fire around them roared.

Chased by swirling coals and sparks, the two brave boys went charging through the crowd, yet no one turned to watch. It was as if young Alejandro and the Indian were unseen, as if they were already spirits on their way to heaven. All the village chanted, “Muerte! Muerte! Muerte!” again. All the village faced the burning barracks. All of Rincón de Dolores called for death to Spaniards, death to traitors, as the two small figures fled invisibly across the plaza to the chapel, where they entered and returned the treasure, the retablo handed down through centuries.

Alone among the village people, only Lupe seemed to see the boys escape. Watching from the shop door, she alone thanked God for yet another year without a tragedy; she alone refused to play the game, the foolish reenactment they all loved so well, pretending blindness as two boys cheated death. Lupe’s imagination would not let her join the celebration of their unofficial saint’s escape from murderous pagans. She had never felt the kiss of flames upon her flesh, but she had suffered from flames nonetheless.

Often Lupe recalled the winter’s night when her father had laid a bed of sticks within the corner fireplace. The flames took hold and a younger Lupe drew her blanket up above her head as other children did when told of ghosts. Even now the memory of resin snapping in the burning wood intruded on her dreams, conjuring a thousand nightmares drawn from Padre Hinojosa’s homilies about Spanish saints who perished in the flames, Agathoclia and Eulalia of Mérida, and the auto de fe, that fearsome ritual of early Mexico, the stake, and acts of faith imposing pain on saint and heretic alike. Her most grievous loss and many sermons, dreams, and sacrifices of the flesh had left her terrified of fire.

Watching from the doorway, Lupe heard a voice. “Do you think this is how it was?”

Although she had not heard him come, a stranger stood beside her, a man in fine dark clothing with full black hair that shimmered slightly in the midday light like the feathers of a crow. From his appearance this man might have been her brother. Like Lupe, he was not tall. Like Lupe, his features called to mind stone carvings of the ancient Mayans. Like Lupe, he had a smooth sloped forehead, pendulous earlobes, and cheekbones high and proud. His golden skin was flawless, as was hers. Like hers, his lips were thick and sensuous, his teeth the flashing white of lightning, his eyes a pair of black pools without bottoms.

“Pardon me, señor?” said Lupe, unaware she might be looking at her twin.

“Do you think this is how it was?” asked the stranger once again. “With Fray Alejandro and the Indian?”

Lupe only shrugged. “Who knows, señor? It is a very old story.”

The stranger nodded, his unfathomable eyes focused on the plaza.

Perhaps, being a stranger, he did not know the story of Fray Alejandro, how the Franciscan had walked two thousand four hundred kilometers to Alta California with two other Fernandino brothers. Because he was a stranger it was possible the man knew nothing of the apostate priests who corrupted Alejandro’s efforts to advance the gospel, how his hope to be the hands and feet of Christ to pagan peoples in the north was undone by Spanish cruelty and indulgence, how Alejandro, forced to flee his beloved mission in the north, had escaped the burning buildings with the Indian, his trusted neophyte companion, the two of them miraculously unseen even as they passed among bloodthirsty savages, much as Saint Peter once had passed his guards in Herod’s prison.

If the man knew nothing of this history he would surely learn that day, for every year at Alejandro’s feast all was reenacted by the village children to commemorate the holy man’s exploits. Rome had thus far not enshrined Fray Alejandro among the saints, but Rincón de Dolores had nonetheless adopted him as their patron, for the man of miracles had settled in their little mountain village when the pagans in the north rejected him, and through many acts of kindness he had become their eternally beloved padre, entrusting them with memories of the mission he had lost up north, somewhere in the hills of Alta California.

Lupe considered speaking to the stranger of these things, but he had departed unobserved. She searched the crowd beyond her door to find him. With the Burning of the Barracks finished now, people strolled throughout the village, passing in the shade of well-trimmed ficus trees around the plaza or along the tiles beneath arched porticos where they haggled with the vendors who had traveled from afar to set up booths for the fiesta. Some of the vendors offered plastic toys for children: balloons, whistles, and balls in a hundred riotous colors. Others hawked recordings of mariachi and norteño music. Sweets, hand tools, shawls, and pottery … everything was there. Near the chapel on the far side of the plaza one could purchase votive candles and milagros, those tiny metal charms that symbolized the miracles requested of the saints. In spite of so much competition, a few still patronized Lupe’s tiendita, her little shop where soda pop and newspapers and other such necessities were offered to the good people of Rincón de Dolores, Jalisco, high in the Sierra Madre mountains.

Forgetting about the stranger, Lupe left her place in the doorway and tended to the customers who visited her shop all afternoon, both villagers and strangers. She took their pesos as the sun outside moved closer to the western mountains and the shadows lengthened. Finally it was almost time for the best part of Fray Alejandro’s fiesta: the gathering at the plaza. The young woman stepped across the stone threshold of her little shop, where the sandals of a dozen generations had shaped a smooth depression. She closed the wooden door. She felt no need for locks. Dressed in a blue cotton skirt and white blouse with a traditional apron, wearing no jewelry and no makeup, with her pure black hair restrained only by a plastic clip, Lupe approached the plaza.

She followed the familia Delgado along the avenida, Rosa and Carlos in their finest clothing normally reserved for Sunday Mass. Rosa’s blouse was perhaps a bit too tight and too low-cut in Lupe’s opinion. Carlos was very handsome with silver tips and silver heel guards on his pointed boots. The three Delgado boys were likewise attired in formal fashion, and the youngest child, darling Linda, toddled on the cobblestones in patent-leather shoes, with petticoats and a pretty pink dress trimmed with sky blue ribbons.

Lupe sometimes wished for children. The thought arose in moments such as this, but it was always fleeting. At other times she praised the Holy Father for her call to chastity. It was good to be unmarried unless one burned with passion, as San Pablo said, and her passion was for Christ.

When Lupe reach the plaza, oh, such a festivity! She saw men at their carts selling little whimsies—empanadas and tamales and nopales from the prickly pear—and strolling toy vendors with helium balloons and plastic snakes on sticks, and groups of girls approaching marriage age who moved about the plaza casting covert glances at the boys whom they pretended to ignore. Soon everyone would laugh as mariachis in the central gazebo serenaded blushing grandmothers, then the people would ignore the mayor as he promised vast improvements through a needless megaphone, and they would admire Rincón de Dolores’s own ballet folklórico, the handsome boys in black charro suits with felt sombreros and shoulders proudly squared, and the beautiful girls in swirling multicolored skirts like rose bouquets.

Lupe traversed the plaza, greeting all as friends, for she was a friend to everyone. Like Fray Alejandro, she longed to be the hands and feet of Christ to them. She went slowly, smiling on her way, touching this one, kissing that one, freely offering her kindness. Normally this bonhomie was as natural as breath to her, but that day it was a kind of sacrifice she offered. It came from force of will. She did not feel it in her heart, and she was uncertain why. Perhaps her dread had lingered since the moment when the barracks flames had nearly claimed two boys. Yes, probably it was only that. Yet she sensed something else at work within her heart, a conviction, and a fear.

On the far side of the plaza Lupe approached the embers of the imitation barracks, a mound of charcoal now, a black mark on the beauty of the day. It frightened her, yet drew her closer. Remarkably, it still emitted smoke. Only Lupe gave attention to that fact. All the others laughed and strolled and savored conversations unawares, but Lupe there beside the blackened ruins felt her pulse increase and heard the beating of her heart within her inner ear. She found it necessary to remind herself to breathe. She saw the smoke still rising like a slender column standing far above the village, straight and true, until it met the burning fringes of the sunset. She turned her face up to the sky and saw the strangest thing among the orange and purple clouds. She saw it, yet it could not be.

“Concha,” called Lupe to a passing friend. “That smoke. Would you look at it?”

The woman, whose seven children swirled around her knees, replied, “I told those foolish men to pour more water on those ashes.”

“But the wind …”

Concha and her perpetually squirming offspring had already passed into the crowd.

Lupe wiped sweating palms upon her apron and tried again to find someone to observe this thing and tell her it was real, but the mariachis had begun their brassy serenades and the people moved away from her, toward the gazebo in the center of the plaza. She stared up at the sky again and asked, “How can that be?”

Someone behind her said, “Perhaps it is a sign.”

Guadalupe Soledad Consuelo de la Garza looked around and saw the stranger with dark hair that shimmered slightly like the feathers of a crow. She felt comforted immediately, for he too had seen the cause of her confusion; he too stood with face turned toward the sky, toward the smoke arising from Fray Alejandro’s ruined mission, the smoke which drifted north against a wind that traveled south.

© 2009 Athol Dickson

EL DÍA DE LOS REYES, 6 DE ENERO DE 1767

LET US BEGIN THE STORY of La Misión de Santa Dolores on the holy day of the three kings, in Italy, in Assisi. To commemorate his twentieth year among the Franciscan brothers, Fray Alejandro Tapia Valdez made a pilgrimage to his beloved San Francisco’s humble chapel, the Porziuncola. For more than a week the friar prayed before the chapel’s frescoes, rarely ceasing for food or sleep. But despite his lengthy praises and petitions, despite his passionate devotion to Almighty God, Fray Alejandro was a pragmatic man. He did not believe the rumor, common in his day, that the frescoes’ perfection was beyond the ability of human hands. As we shall see, in time the friar would reconsider.

The Franciscan stood five feet four inches tall, an average Spaniard’s height in the eighteenth century. He was broad and unattractive. Heavy whiskers lurked beneath the surface of his jaw, darkly threatening to burst forth. Fray Alejandro’s brow was large and loomed above the recess of his eyes as if it were a cliff eroded by the pounding of the sea, ready to crash down at any moment. The black fullness of his hair had been shaved at the crown, leaving only a circular fringe around the edges of his head. His nose, once aquiline and proud, had become a perpetual reminder of the violence that had flattened it at some time in the past.

For all its ugliness, Fray Alejandro’s visage could not mask the gentleness within. His crooked smile shed warmth upon his fellow man. His hands were ever ready with a touch to reassure or steady, or to simply grant the gift of human presence. When someone spoke, be that person wise or not, he inclined his head and listened with his entire being, as if the speaker’s words had all the weight of holy writ. In his eyes was love.

Love does not defend against the sorrows of this world, of course. On the contrary, each day as Fray Alejandro knelt in prayer at the Porziuncola he became more deeply troubled. His imagination had recently been captured by strange stories of the heathen natives of the New World, isolated wretches with no knowledge of their Savior. This tragedy grew in Alejandro’s mind until he groaned aloud in sympathy for their unhappy souls. Other brothers kneeling on his left and right cast covert glances at him. Many thought his noisy prayers an uncouth intrusion, but caught up as he was in sacred agony, Alejandro did not notice.

Then came that holy day of the three kings, when in the midst of his entreaties for the pagans of New Spain, Fray Alejandro suddenly felt a painful heat as if his body were ablaze. In this, the first of his three burnings, Alejandro became faint. He heard a whisper saying, “Go and save my children.” The bells began to peal, although it was later said the ropes had not been touched. As startled pigeons burst forth from the bell tower, Alejandro rose.

How like the Holy Father to command such a journey on that day of days! Without a backward glance Fray Alejandro strode away from San Francisco’s little chapel as if following a star, determined to return at once to Hornachuelos, in Córdoba, there to seek permission from the abbot of the monastery of Santa María de los Ángeles for a voyage to New Spain.

The abbot’s assent was quickly given, but Fray Alejandro spent many months waiting on the vast bureaucracy of King Carlos III to approve his passage. Still, while the wheels of government turn slowly, slowly they do turn.

Finally, in late May of the year 1767, the good friar stood at the bulwarks of a galleon in the West Indian Fleet, tossed by the Atlantic, quite ill, and protected from the frigid spray by nothing but his robe of coarse handmade cloth. In spite of the pitching deck, always Alejandro faced New Spain, far beyond the horizon. His short, broad body seemed to strain against the wind and ocean waves with eagerness to be about his Father’s business.

But let us be more patient than the friar, for this is just the first of many journeys we shall follow as our story leads us back and forth through space and time. Indeed, the events Fray Alejandro has set in motion have their culmination far into the future. Therefore, leaving the Franciscan and his solitary ship, we cross many miles to reach a village known as Rincón de Dolores, high among the Sierra Madre mountains of Jalisco, Mexico. And we fly further still, centuries ahead of Alejandro, to find ourselves in these, our modern times.

Accompanied by norteño music blaring from loudspeakers and by much celebratory honking of automobile horns, we observe the burning of a makeshift structure of twigs and sticks and painted cardboard, which seemed a more substantial thing once it was engulfed, as if the busy flames were masons hard at work with red adobe. The people of the village of Rincón de Dolores were encouraged by the firmness of the fire. All the village cheered as the imitation barracks burned before them. They cheered, and with their jolly voices dared a pair of boys to stay in the inferno just a little longer.

There was much to enjoy on that Feast Day of Fray Alejandro—the floral garlands, the children in their antique costumes, the pinwheels spun by crackling fireworks, the somber procession of the saints along the avenida—but one citizen did not join the festivities.

Guadalupe Soledad Consuelo de la Garza trembled as she watched the flaming reenactment of the tragedy of La Misión de Santa Dolores. Who knew, but possibly this year the boys would stay too long within the flames? Who knew, but possibly this time the sticks would burn, the cardboard become ash and rise into the sky, and “Alejandro” and “the Indian” would not emerge? Spurred to foolishness by those who called for courage, might this be the year when merrymaking turned to mourning? The young woman with the long name—let us call her merely Lupe—feared it might be so, while the imitation barracks burned and the boys remained inside.

As was their ancient custom, after the fire was set by eager boys in Indian costumes, the village people chanted, “Muerte! Muerte! Muerte! Death to Spaniards! Death to traitors!” Their refrain arose in tandem with the flames. Only when the fire ascended to the middle of the mock barracks’ spindly walls did some within the crowd begin to yell, “Salid! Salid! Salid!” Come out! they called, a few of them at first, mostly girls and women, then as the minutes slowly passed this call became predominant, until the entire village shouted it as one, Come out! and the boys inside could flee the fire with honor.

Yet they did not come.

“Agua!” someone shouted, probably the boys’ parents, and nearby men with buckets hurried toward the crackling barracks walls. “Agua, rápido!” they shouted, and the first man swung his bucket back, prepared to douse a small part of the flames.

Such wild and forceful flames, and so little water, thought young Lupe. Holy Father, please protect them.

Even as she prayed, the first man thrust his bucket forward. Water sizzled in the burning sticks and rose as steam, and from the conflagration burst two little figures. One boy came out robed from head to foot in gray cloth, the cincture at his waist knotted in three places to bring poverty, obedience, and chastity to mind. He carried a bundle, the sacred retablo of Fray Alejandro concealed in crimson velvet, a small altarpiece which no one but Padre Hinojosa, the village priest, would ever see. The other boy came nearly naked with only a covering of sackcloth, his bare arms and legs agleam with aloe sap as protection from the heat. The fire around them roared.

Chased by swirling coals and sparks, the two brave boys went charging through the crowd, yet no one turned to watch. It was as if young Alejandro and the Indian were unseen, as if they were already spirits on their way to heaven. All the village chanted, “Muerte! Muerte! Muerte!” again. All the village faced the burning barracks. All of Rincón de Dolores called for death to Spaniards, death to traitors, as the two small figures fled invisibly across the plaza to the chapel, where they entered and returned the treasure, the retablo handed down through centuries.

Alone among the village people, only Lupe seemed to see the boys escape. Watching from the shop door, she alone thanked God for yet another year without a tragedy; she alone refused to play the game, the foolish reenactment they all loved so well, pretending blindness as two boys cheated death. Lupe’s imagination would not let her join the celebration of their unofficial saint’s escape from murderous pagans. She had never felt the kiss of flames upon her flesh, but she had suffered from flames nonetheless.

Often Lupe recalled the winter’s night when her father had laid a bed of sticks within the corner fireplace. The flames took hold and a younger Lupe drew her blanket up above her head as other children did when told of ghosts. Even now the memory of resin snapping in the burning wood intruded on her dreams, conjuring a thousand nightmares drawn from Padre Hinojosa’s homilies about Spanish saints who perished in the flames, Agathoclia and Eulalia of Mérida, and the auto de fe, that fearsome ritual of early Mexico, the stake, and acts of faith imposing pain on saint and heretic alike. Her most grievous loss and many sermons, dreams, and sacrifices of the flesh had left her terrified of fire.

Watching from the doorway, Lupe heard a voice. “Do you think this is how it was?”

Although she had not heard him come, a stranger stood beside her, a man in fine dark clothing with full black hair that shimmered slightly in the midday light like the feathers of a crow. From his appearance this man might have been her brother. Like Lupe, he was not tall. Like Lupe, his features called to mind stone carvings of the ancient Mayans. Like Lupe, he had a smooth sloped forehead, pendulous earlobes, and cheekbones high and proud. His golden skin was flawless, as was hers. Like hers, his lips were thick and sensuous, his teeth the flashing white of lightning, his eyes a pair of black pools without bottoms.

“Pardon me, señor?” said Lupe, unaware she might be looking at her twin.

“Do you think this is how it was?” asked the stranger once again. “With Fray Alejandro and the Indian?”

Lupe only shrugged. “Who knows, señor? It is a very old story.”

The stranger nodded, his unfathomable eyes focused on the plaza.

Perhaps, being a stranger, he did not know the story of Fray Alejandro, how the Franciscan had walked two thousand four hundred kilometers to Alta California with two other Fernandino brothers. Because he was a stranger it was possible the man knew nothing of the apostate priests who corrupted Alejandro’s efforts to advance the gospel, how his hope to be the hands and feet of Christ to pagan peoples in the north was undone by Spanish cruelty and indulgence, how Alejandro, forced to flee his beloved mission in the north, had escaped the burning buildings with the Indian, his trusted neophyte companion, the two of them miraculously unseen even as they passed among bloodthirsty savages, much as Saint Peter once had passed his guards in Herod’s prison.

If the man knew nothing of this history he would surely learn that day, for every year at Alejandro’s feast all was reenacted by the village children to commemorate the holy man’s exploits. Rome had thus far not enshrined Fray Alejandro among the saints, but Rincón de Dolores had nonetheless adopted him as their patron, for the man of miracles had settled in their little mountain village when the pagans in the north rejected him, and through many acts of kindness he had become their eternally beloved padre, entrusting them with memories of the mission he had lost up north, somewhere in the hills of Alta California.

Lupe considered speaking to the stranger of these things, but he had departed unobserved. She searched the crowd beyond her door to find him. With the Burning of the Barracks finished now, people strolled throughout the village, passing in the shade of well-trimmed ficus trees around the plaza or along the tiles beneath arched porticos where they haggled with the vendors who had traveled from afar to set up booths for the fiesta. Some of the vendors offered plastic toys for children: balloons, whistles, and balls in a hundred riotous colors. Others hawked recordings of mariachi and norteño music. Sweets, hand tools, shawls, and pottery … everything was there. Near the chapel on the far side of the plaza one could purchase votive candles and milagros, those tiny metal charms that symbolized the miracles requested of the saints. In spite of so much competition, a few still patronized Lupe’s tiendita, her little shop where soda pop and newspapers and other such necessities were offered to the good people of Rincón de Dolores, Jalisco, high in the Sierra Madre mountains.

Forgetting about the stranger, Lupe left her place in the doorway and tended to the customers who visited her shop all afternoon, both villagers and strangers. She took their pesos as the sun outside moved closer to the western mountains and the shadows lengthened. Finally it was almost time for the best part of Fray Alejandro’s fiesta: the gathering at the plaza. The young woman stepped across the stone threshold of her little shop, where the sandals of a dozen generations had shaped a smooth depression. She closed the wooden door. She felt no need for locks. Dressed in a blue cotton skirt and white blouse with a traditional apron, wearing no jewelry and no makeup, with her pure black hair restrained only by a plastic clip, Lupe approached the plaza.

She followed the familia Delgado along the avenida, Rosa and Carlos in their finest clothing normally reserved for Sunday Mass. Rosa’s blouse was perhaps a bit too tight and too low-cut in Lupe’s opinion. Carlos was very handsome with silver tips and silver heel guards on his pointed boots. The three Delgado boys were likewise attired in formal fashion, and the youngest child, darling Linda, toddled on the cobblestones in patent-leather shoes, with petticoats and a pretty pink dress trimmed with sky blue ribbons.

Lupe sometimes wished for children. The thought arose in moments such as this, but it was always fleeting. At other times she praised the Holy Father for her call to chastity. It was good to be unmarried unless one burned with passion, as San Pablo said, and her passion was for Christ.

When Lupe reach the plaza, oh, such a festivity! She saw men at their carts selling little whimsies—empanadas and tamales and nopales from the prickly pear—and strolling toy vendors with helium balloons and plastic snakes on sticks, and groups of girls approaching marriage age who moved about the plaza casting covert glances at the boys whom they pretended to ignore. Soon everyone would laugh as mariachis in the central gazebo serenaded blushing grandmothers, then the people would ignore the mayor as he promised vast improvements through a needless megaphone, and they would admire Rincón de Dolores’s own ballet folklórico, the handsome boys in black charro suits with felt sombreros and shoulders proudly squared, and the beautiful girls in swirling multicolored skirts like rose bouquets.

Lupe traversed the plaza, greeting all as friends, for she was a friend to everyone. Like Fray Alejandro, she longed to be the hands and feet of Christ to them. She went slowly, smiling on her way, touching this one, kissing that one, freely offering her kindness. Normally this bonhomie was as natural as breath to her, but that day it was a kind of sacrifice she offered. It came from force of will. She did not feel it in her heart, and she was uncertain why. Perhaps her dread had lingered since the moment when the barracks flames had nearly claimed two boys. Yes, probably it was only that. Yet she sensed something else at work within her heart, a conviction, and a fear.

On the far side of the plaza Lupe approached the embers of the imitation barracks, a mound of charcoal now, a black mark on the beauty of the day. It frightened her, yet drew her closer. Remarkably, it still emitted smoke. Only Lupe gave attention to that fact. All the others laughed and strolled and savored conversations unawares, but Lupe there beside the blackened ruins felt her pulse increase and heard the beating of her heart within her inner ear. She found it necessary to remind herself to breathe. She saw the smoke still rising like a slender column standing far above the village, straight and true, until it met the burning fringes of the sunset. She turned her face up to the sky and saw the strangest thing among the orange and purple clouds. She saw it, yet it could not be.

“Concha,” called Lupe to a passing friend. “That smoke. Would you look at it?”

The woman, whose seven children swirled around her knees, replied, “I told those foolish men to pour more water on those ashes.”

“But the wind …”

Concha and her perpetually squirming offspring had already passed into the crowd.

Lupe wiped sweating palms upon her apron and tried again to find someone to observe this thing and tell her it was real, but the mariachis had begun their brassy serenades and the people moved away from her, toward the gazebo in the center of the plaza. She stared up at the sky again and asked, “How can that be?”

Someone behind her said, “Perhaps it is a sign.”

Guadalupe Soledad Consuelo de la Garza looked around and saw the stranger with dark hair that shimmered slightly like the feathers of a crow. She felt comforted immediately, for he too had seen the cause of her confusion; he too stood with face turned toward the sky, toward the smoke arising from Fray Alejandro’s ruined mission, the smoke which drifted north against a wind that traveled south.

© 2009 Athol Dickson

Descriere

When a construction project unearths a lost Spanish mission, four people mustchoose: serve a greater good, or hold fast to some basic moral value?

Notă biografică

Premii

- Christy Awards Winner, 2010

- INSPYs the Bloggers Awards for Excellence in Faith-Driven Literature Finalist, 2010