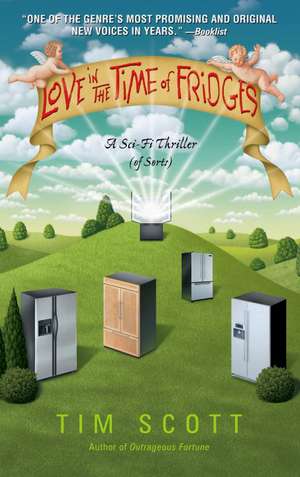

Love in the Time of Fridges

Autor Tim Scotten Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 iun 2008

“New Seattle Health and Safety. Do not die for no reason.” This is the motto of a city so obsessed with the danger of sharp corners that it has almost forgotten how to live. But Huckleberry Lindbergh is about to find his trip to the city most decidedly unsafe. For a chance encounter leads him into the heart of a dark conspiracy. And in order to stop it, this former cop is about to do something so unsafe—so monumentally stupid—that its reverberations will be felt all the way to the Pentagon.

Soon he is on the run from more authorities than he has had hot meals, his staunchest allies a bunch of feral fridges that give new meaning to the words “chill out.” But sometimes a dose of chaos is just what the doctor ordered, and Huck’s quest to remain among the living teaches not only him but those around him the true meaning of survival . . . in all its forms.

Preț: 119.03 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 179

Preț estimativ în valută:

22.78€ • 23.53$ • 18.96£

22.78€ • 23.53$ • 18.96£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 04-18 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780553384413

ISBN-10: 0553384414

Pagini: 364

Dimensiuni: 132 x 208 x 22 mm

Greutate: 0.28 kg

Editura: Spectra Books

ISBN-10: 0553384414

Pagini: 364

Dimensiuni: 132 x 208 x 22 mm

Greutate: 0.28 kg

Editura: Spectra Books

Notă biografică

Tim Scott graduated from Cambridge University, England, and decided to use his hard fought education to work a plasterer, decorator and delivery driver.

He writing career began with a training video which warned office staff that falling over could be dangerous. He then went on to write and appear on BBC Radio 4 in around fifty comedy half hours—and finally ended up being given his own late night comedy television series on network ITV. It ran for twenty six episodes and was so surreal that even Ionesco or Salvador Dali would have been shaking their heads in confusion.

He has written a large number of children's books, and also for children's television. He more recently became a television director and in 2003 won a BAFTA for co writing and directing a children's series, "Ripley and Scuff," for the BBC. He likes to travel around the world, often in search of surf.

He writing career began with a training video which warned office staff that falling over could be dangerous. He then went on to write and appear on BBC Radio 4 in around fifty comedy half hours—and finally ended up being given his own late night comedy television series on network ITV. It ran for twenty six episodes and was so surreal that even Ionesco or Salvador Dali would have been shaking their heads in confusion.

He has written a large number of children's books, and also for children's television. He more recently became a television director and in 2003 won a BAFTA for co writing and directing a children's series, "Ripley and Scuff," for the BBC. He likes to travel around the world, often in search of surf.

Extras

Chapter One

ONE DAY LATER

I didn't know her then.

Not when she stepped into the tiny drongle and sat down, soaked through, her slim lips mouthing a faint curse, her brown eyes a stark echo of someone I had once known.

The drongle had just clattered under the concrete snarl of New Seattle's main gate, carrying me back into a city that I had not seen for eight years.

My life had gone missing since I had last been here, mislaid among too many motels, too many bad memories, and a never-ending succession of nights fogged with the bittersweet taste of mojitos. I stared out at the gleaming city lights star-bursting through the rain.

I had tried to close the door on all that had happened here. But that door had never quite shut, and the past had seeped out in a deathly trickle, contaminating my life.

And now I was back, watching the city slump by, pretending these awkward, unfamiliar buildings were my home. We passed a new city sign that shone with garish insincerity in the rain:

WELCOME!

New Seattle Welcomes Visitors*

*See exclusions

A billboard with a huge list of exclusions rose up behind it and I caught the words real estate agents somewhere near the bottom. They were resented in a lot of places now, and actually hunted down in Texas by bounty hunters, because the residents had lost patience after being randomly sent inappropriate house details time after time.

The drongle juddered to a halt and the sign loomed over us. It seemed unlikely anyone had ever actually read all that small print, however much it constituted part of the legal agreement to enter this city. It would have probably ranked as the dullest half hour of my life, and I had once talked to a man at a party who was a real fan of scat singing.

I tilted my head as we passed by and saw a bird sitting on the top, motionless, staring down, and the image sat frozen in my mind as we shuddered on through the streets. When it faded I saw the girl was wrapped in her own thoughts, and her deep brown eyes appeared lost in an alleyway of her past.

A Health and Safety sign rose up behind her, filling the drongle dome with a screaming green light.

"New Seattle Health and Safety asks you to stay safe! Be careful of apple pie filling! It's absurdly hot! A strong Health and Safety Department means a strong city!"

I had seen a handful of these signs already and I had read somewhere that the H and S Department wielded the political power behind the machinations of the west coast of America now, and especially in New Seattle. The department had become so powerful it even had an army and had invaded Denmark a few years before. It claimed the war was necessary to settle an international disagreement over the use of hard hats. Eventually, after it had taken over most of Copenhagen, a protracted truce was agreed. Health and Safety published several Venn diagrams to prove that more people wore bright reflective clothing in Denmark than they had previously and this, they claimed, meant victory. So they left.

Although two thousand people died in the fighting, nobody cared too much. It was a long way away, and wars in other people's countries don't really count. Except to some life-shattered veterans who probably walked through the crowds in the mall on a Saturday afternoon drunkenly telling a story in snatches that no one wanted to hear.

The drongle rattled to a halt behind a line of others in the splattering rain, and I felt a prick of frustration. I had been in this city less than fifteen minutes and I was already about to be hassled at a police checkpoint.

The girl's eyes came back and looked around.

"Thank you for traveling today," said the drongle. "Your lucky color is blue. Your lucky artist who died miserably is Toulouse-Lautrec. Please take the receipt that is being printed. It may contain traces of nuts, so if you are allergic to nuts, use the gloves provided." A sheaf of paper spewed out, along with some gloves, from a small slot, but neither the girl nor myself made any move for them.

We just sat with leashed-up frustration without exchanging a word as the rain teemed down, smattering the roof with a heavy thumping cry, as though the gods were not just angry, but insane.

Welcome home, I thought, trying to believe the cops would just wave us through with a glare. The minutes passed until finally they crisscrossed the translucent dome with flashlights before hauling open the door, their black ponchos reflecting silver streaks in the lights.

"Out of the car, please," said a voice.

"What's the problem, Officer?" I said, really not in the mood to be hassled by a bunch of rookies.

"No problem. Just step out of the drongle, please, both of you."

So we got out and stood waiting in the teeming rain as they hassled the people in the drongle ahead amid a flurry of don't-fuck-with-me faces. It seemed some hoods had pulled off a downtown robbery and these cops were trawling for evidence from anyone they could find. And right now, that was me.

The rain pattered and slapped on everything it could find, and above us another huge New Seattle Health and Safety sign flashed in the wet. "Beware! Treading on small toy building blocks when only wearing socks really hurts."

"You just in?" said a different cop with a flashlight walking over.

"Yeah, that's right." I tried to sound polite, but the brightness in my voice got lost in the storm.

Eventually, another cop trudged over with the rain sliding off his poncho in rivulets and gathering on the peak of his cap in a long line of playful drops.

I had a feed on the back of my neck like everyone else. He plugged in, and a twist of looping wire spooled from the jack plug to his Handheld Feed Reader.

I felt a cold jolt in my neck.

"You showed up as only just in. We tracked your drongle. We like to check out strangers," said the first cop.

"I'm not a stranger. I was born here. I lived here until eight years ago."

"Registered in New York State," said the cop scrolling through my details on his handheld. The system saved cutting through a lot of crap. Sometimes people had their profiles altered on their feed, but if you knew what you were looking for, you could usually tell.

"What's your business?" The first cop shone the flashlight in my face, and I squinted into the glare.

"I'm looking up an old friend, Gabe Numan."

"Old friend, huh?"

"Yeah."

"Hey! He's an ex-New Seattle cop," said the one still scrolling through my details on the screen. "Huckleberry Lindbergh."

"That right?"

"Yeah. Once upon a time," I confirmed.

"Kicked out?"

"I left for my own reasons."

"Couldn't hack it?"

"No, I just left."

"Sure. You left. Let's hear his mood."

The mood program played a few bars of music that was meant to represent your mood. For some reason mine played something classical–a heavy, brooding piece that might have been banged out by a Russian composer after a night on the vodka. It sounded melancholy in the rain.

"I don't like that. That doesn't sound right. What kind of mood is that?" said the cop with the flashlight. "Take him off to Head Hack Central–and the girl, too. If there's one group of people you can't trust, it's cops who got kicked out. They hold a grudge."

"Hey!" cried the woman. "We're not together. I'm not with this guy!"

That was the first time I noticed the fire in her eyes. Even through the snapping drops of rain, I could see it burn.

"Hey, calm down, lady," said the cop, pocketing his flashlight. "If you've nothing to hide, you'll be out within the hour. Just routine. Normally we use the street booths, but they're all broken around here. Now get a red tag and some cuffs on these two and get them in a drongle."

Welcome home, Huck, I thought. Welcome home.

Chapter Two

My hands were cuffed and a thin red collar snapped onto my neck. They did the same to the girl. It wasn't comfortable. Then we were herded into a four-man cop drongle and, after I kicked up a commotion, they retrieved my bag and threw it in after me.

An officer stooped inside, pulled the hood shut with a grinding crack, and sat with his legs apart, chewing gum and treating the world with enough disinterest to power a small country.

As the drongle rattled away into the night, the hard, wet seats felt cold and soulless. Several tiny screens flickered into life, and the image of a small man with short, neat hair and overlarge eyebrows appeared. For a moment, his words ran out of sync with his mouth, and then the two fused together.

"Hi, I'm Dan Cicero, mayor of New Seattle. You might have heard of me. People call me the Mayor of Safety." He pulled an overly serious expression that played havoc with his eyebrows. Neither seemed to know which way to go. "We have a zero-tolerance policy on danger in this city. If you feel scared–or even nervous about anything–call our slightly-on-edge help line, where a counselor will be happy to talk to you about nice things like pet rabbits." His eyebrows returned to their default setting, then the left one began to head off. "New Seattle Health and Safety is the finest in the world. And certainly a lot better than anything they have in Chicago. Their safety mascot is a piece of crap. An absolute piece of high-end crap. So enjoy your visit."

"New Seattle Health and Safety," sang a close harmony group as pictures of the city were splayed across the screen. "Stay safe! Watch out! Stay safe! Watch out for that–"

Then the drawn-out sound of a long, tortuous crash.

And the mayor's face again.

"And remember, please don't die for no reason. I mean, what's the point? Right?" Then the screen flickered, went black, and those last words hung in the air mocking me, daring me to stir up my anger.

"Don't die for no reason? Why does he say that?"

"It's just a slogan," said the cop.

"A slogan? Sometimes people do die for no reason. Isn't that obvious?"

"If you say so."

The noise of the drongle wheels crunched over the conversation.

I closed my eyes trying to breathe away the anger provoked by that absurd slogan. But the more I pushed it away the more it came back. And the more the memories waited in line in my head.

Another back-wrenching jolt and I looked up.

The woman was quiet. Her features had a soft warmth, but her dark eyes were wrapped up with thoughts I couldn't begin to read. Maybe she saw bad memories running like reels of film in her mind. Maybe she was a prisoner of the past as well.

She barely saw the streets slip by; barely saw the crowds on the drenched sidewalks, the posters, the hawkers and sellers, the bedraggled skyline of skyscrapers, each with tethered advertising balloons bobbing in the wind and their sides a maelstrom of pinprick-white lights star-bursting through the evening gloom, proclaiming the merits of some must-have, must-buy, must-show-off item.

Her eyes remained lost in another place and I wondered why.

Another H and S sign limped past. "Do not open beer bottles with your teeth when you are drunk. You will only realize this is a bad idea the next morning." Who were they kidding?

I recognized the building near it. It was by the Business Center for Not Answering Questions. I remembered how, at one time, it had been a popular institution, giving high-profile talks on the importance of not answering too many questions in business because it had been proven to cut into profits. It was rumored that if anyone ever tried to clarify anything they said, they simply ignored them.

Or sometimes they all put on hats and pretended to be French.

More buildings passed by, but the new architecture just looked like secondhand ideas served up cold, seeping disdain into the city. I didn't like it.

Finally we thumped through a gate and into a massive lot heaving with police drongles–some empty, and others disgorging people into the night.

The cop chewing gum opened the hood with a grunt, shoved my bag into my cuffed hands, and nodded. It was pouring rain as we climbed out and wove our way through the puddles and across the drenched lot that sparkled with reflected lights.

Head Hack Central was lit up with glowing red columns of light. The building was meant to look like it came from classical Greece, but the facade was more like a cross between a wedding cake and a nativity display.

I had been here as a cop.

As we walked through the massive worn doors and into a lobby, memories came at me, one after the other, like stones dropped in a still pool. But I ignored them all. There would be plenty of time to trawl the memories of this place and I wasn't interested in doing that yet. I had been traveling for what seemed like a decade, and right now I just needed to get out of here and find a bed.

We were led down a corridor lined with offices. The woman was taking it all in. It occurred to me she was looking for a way out, and I suddenly felt a frisson of pity for her. Now I understood why she had been caught up in her thoughts in the drongle.

She had something to hide.

Chapter Three

The use of the color red was restricted in New Seattle, because the cops held the franchise. That's why they carried small red truncheons and guns, because it was a marketing thing. I learned all this from a chubby cop who chattered good-naturedly as he left the two of us in a small temporary holding area, composed of a dozen seats enclosed by a small cage. He kept my bag, saying I could pick it up on the way out.

A few other people were already waiting under the glare of a harsh fluorescent light that doused the area with a particularly soulless sense of inhumanity. Across from me was a gaunt man, staring off at things only he could see. His limp-waisted appearance made it appear as though his body had been blown up without quite enough air, and his thin lips didn't seem as if they would have any words behind them. He saw me and smiled, and it creased up more of his face than expected. The girl paced slowly around, still taking in the layout, and I wondered if she would make a bolt for it when they took off our cuffs.

Then someone else was brought in, remonstrating fiercely with a cop. "But I have a license to drop melons," he was saying. His voice was thick with phlegm, and he dripped water from a blotchy raincoat.

"Sure you do," said the cop, shoving him through the gate and leaning his bulging shopping bag up against the desk.

"I do. I have it here. You want to see it?"

"There's no such thing as a license to drop ripe melons from the roofs of very high buildings," said the cop. "Make yourself comfortable. We'll call you."

"But I have license. Where's the thing?" He began to thumb through his raincoat pockets, pulling out a variety of dirty objects. "I got it from the State Department. It cost me fifty dollars. Hey–you see? Here!" He flourished a piece of paper and shoved it through the bars.

"You write this yourself?" said the cop, handing it back.

"No! It's a genuine license to drop ripe melons from the roof of tall buildings. Genuine! You haven't read it, have you? An official melon license. Ah, goddamn it. Cops!" He took the thing back, rammed it into his pocket, and sat down grouchily across from us. I could see a melon protruding from the top of his shopping bag by the main desk.

I sat back and closed my eyes, and realized the smell of disinfectant in this place hadn't changed at all. Another cascade of memories came at me, bright and clear.

Then a tiny voice filled me with a shiver, and it took me a moment to realize that it was someone whispering in my ear.

"They say there's another city like this one, but it is empty," it said, and I opened my eyes and turned.

It was an old man.

"What?" His deep blue eyes sparkled and then he leaned close to my ear again and whispered, "A place where there are no people. And you walk through and there's not a sound. Just the empty buildings. I've dreamed of it."

ONE DAY LATER

I didn't know her then.

Not when she stepped into the tiny drongle and sat down, soaked through, her slim lips mouthing a faint curse, her brown eyes a stark echo of someone I had once known.

The drongle had just clattered under the concrete snarl of New Seattle's main gate, carrying me back into a city that I had not seen for eight years.

My life had gone missing since I had last been here, mislaid among too many motels, too many bad memories, and a never-ending succession of nights fogged with the bittersweet taste of mojitos. I stared out at the gleaming city lights star-bursting through the rain.

I had tried to close the door on all that had happened here. But that door had never quite shut, and the past had seeped out in a deathly trickle, contaminating my life.

And now I was back, watching the city slump by, pretending these awkward, unfamiliar buildings were my home. We passed a new city sign that shone with garish insincerity in the rain:

WELCOME!

New Seattle Welcomes Visitors*

*See exclusions

A billboard with a huge list of exclusions rose up behind it and I caught the words real estate agents somewhere near the bottom. They were resented in a lot of places now, and actually hunted down in Texas by bounty hunters, because the residents had lost patience after being randomly sent inappropriate house details time after time.

The drongle juddered to a halt and the sign loomed over us. It seemed unlikely anyone had ever actually read all that small print, however much it constituted part of the legal agreement to enter this city. It would have probably ranked as the dullest half hour of my life, and I had once talked to a man at a party who was a real fan of scat singing.

I tilted my head as we passed by and saw a bird sitting on the top, motionless, staring down, and the image sat frozen in my mind as we shuddered on through the streets. When it faded I saw the girl was wrapped in her own thoughts, and her deep brown eyes appeared lost in an alleyway of her past.

A Health and Safety sign rose up behind her, filling the drongle dome with a screaming green light.

"New Seattle Health and Safety asks you to stay safe! Be careful of apple pie filling! It's absurdly hot! A strong Health and Safety Department means a strong city!"

I had seen a handful of these signs already and I had read somewhere that the H and S Department wielded the political power behind the machinations of the west coast of America now, and especially in New Seattle. The department had become so powerful it even had an army and had invaded Denmark a few years before. It claimed the war was necessary to settle an international disagreement over the use of hard hats. Eventually, after it had taken over most of Copenhagen, a protracted truce was agreed. Health and Safety published several Venn diagrams to prove that more people wore bright reflective clothing in Denmark than they had previously and this, they claimed, meant victory. So they left.

Although two thousand people died in the fighting, nobody cared too much. It was a long way away, and wars in other people's countries don't really count. Except to some life-shattered veterans who probably walked through the crowds in the mall on a Saturday afternoon drunkenly telling a story in snatches that no one wanted to hear.

The drongle rattled to a halt behind a line of others in the splattering rain, and I felt a prick of frustration. I had been in this city less than fifteen minutes and I was already about to be hassled at a police checkpoint.

The girl's eyes came back and looked around.

"Thank you for traveling today," said the drongle. "Your lucky color is blue. Your lucky artist who died miserably is Toulouse-Lautrec. Please take the receipt that is being printed. It may contain traces of nuts, so if you are allergic to nuts, use the gloves provided." A sheaf of paper spewed out, along with some gloves, from a small slot, but neither the girl nor myself made any move for them.

We just sat with leashed-up frustration without exchanging a word as the rain teemed down, smattering the roof with a heavy thumping cry, as though the gods were not just angry, but insane.

Welcome home, I thought, trying to believe the cops would just wave us through with a glare. The minutes passed until finally they crisscrossed the translucent dome with flashlights before hauling open the door, their black ponchos reflecting silver streaks in the lights.

"Out of the car, please," said a voice.

"What's the problem, Officer?" I said, really not in the mood to be hassled by a bunch of rookies.

"No problem. Just step out of the drongle, please, both of you."

So we got out and stood waiting in the teeming rain as they hassled the people in the drongle ahead amid a flurry of don't-fuck-with-me faces. It seemed some hoods had pulled off a downtown robbery and these cops were trawling for evidence from anyone they could find. And right now, that was me.

The rain pattered and slapped on everything it could find, and above us another huge New Seattle Health and Safety sign flashed in the wet. "Beware! Treading on small toy building blocks when only wearing socks really hurts."

"You just in?" said a different cop with a flashlight walking over.

"Yeah, that's right." I tried to sound polite, but the brightness in my voice got lost in the storm.

Eventually, another cop trudged over with the rain sliding off his poncho in rivulets and gathering on the peak of his cap in a long line of playful drops.

I had a feed on the back of my neck like everyone else. He plugged in, and a twist of looping wire spooled from the jack plug to his Handheld Feed Reader.

I felt a cold jolt in my neck.

"You showed up as only just in. We tracked your drongle. We like to check out strangers," said the first cop.

"I'm not a stranger. I was born here. I lived here until eight years ago."

"Registered in New York State," said the cop scrolling through my details on his handheld. The system saved cutting through a lot of crap. Sometimes people had their profiles altered on their feed, but if you knew what you were looking for, you could usually tell.

"What's your business?" The first cop shone the flashlight in my face, and I squinted into the glare.

"I'm looking up an old friend, Gabe Numan."

"Old friend, huh?"

"Yeah."

"Hey! He's an ex-New Seattle cop," said the one still scrolling through my details on the screen. "Huckleberry Lindbergh."

"That right?"

"Yeah. Once upon a time," I confirmed.

"Kicked out?"

"I left for my own reasons."

"Couldn't hack it?"

"No, I just left."

"Sure. You left. Let's hear his mood."

The mood program played a few bars of music that was meant to represent your mood. For some reason mine played something classical–a heavy, brooding piece that might have been banged out by a Russian composer after a night on the vodka. It sounded melancholy in the rain.

"I don't like that. That doesn't sound right. What kind of mood is that?" said the cop with the flashlight. "Take him off to Head Hack Central–and the girl, too. If there's one group of people you can't trust, it's cops who got kicked out. They hold a grudge."

"Hey!" cried the woman. "We're not together. I'm not with this guy!"

That was the first time I noticed the fire in her eyes. Even through the snapping drops of rain, I could see it burn.

"Hey, calm down, lady," said the cop, pocketing his flashlight. "If you've nothing to hide, you'll be out within the hour. Just routine. Normally we use the street booths, but they're all broken around here. Now get a red tag and some cuffs on these two and get them in a drongle."

Welcome home, Huck, I thought. Welcome home.

Chapter Two

My hands were cuffed and a thin red collar snapped onto my neck. They did the same to the girl. It wasn't comfortable. Then we were herded into a four-man cop drongle and, after I kicked up a commotion, they retrieved my bag and threw it in after me.

An officer stooped inside, pulled the hood shut with a grinding crack, and sat with his legs apart, chewing gum and treating the world with enough disinterest to power a small country.

As the drongle rattled away into the night, the hard, wet seats felt cold and soulless. Several tiny screens flickered into life, and the image of a small man with short, neat hair and overlarge eyebrows appeared. For a moment, his words ran out of sync with his mouth, and then the two fused together.

"Hi, I'm Dan Cicero, mayor of New Seattle. You might have heard of me. People call me the Mayor of Safety." He pulled an overly serious expression that played havoc with his eyebrows. Neither seemed to know which way to go. "We have a zero-tolerance policy on danger in this city. If you feel scared–or even nervous about anything–call our slightly-on-edge help line, where a counselor will be happy to talk to you about nice things like pet rabbits." His eyebrows returned to their default setting, then the left one began to head off. "New Seattle Health and Safety is the finest in the world. And certainly a lot better than anything they have in Chicago. Their safety mascot is a piece of crap. An absolute piece of high-end crap. So enjoy your visit."

"New Seattle Health and Safety," sang a close harmony group as pictures of the city were splayed across the screen. "Stay safe! Watch out! Stay safe! Watch out for that–"

Then the drawn-out sound of a long, tortuous crash.

And the mayor's face again.

"And remember, please don't die for no reason. I mean, what's the point? Right?" Then the screen flickered, went black, and those last words hung in the air mocking me, daring me to stir up my anger.

"Don't die for no reason? Why does he say that?"

"It's just a slogan," said the cop.

"A slogan? Sometimes people do die for no reason. Isn't that obvious?"

"If you say so."

The noise of the drongle wheels crunched over the conversation.

I closed my eyes trying to breathe away the anger provoked by that absurd slogan. But the more I pushed it away the more it came back. And the more the memories waited in line in my head.

Another back-wrenching jolt and I looked up.

The woman was quiet. Her features had a soft warmth, but her dark eyes were wrapped up with thoughts I couldn't begin to read. Maybe she saw bad memories running like reels of film in her mind. Maybe she was a prisoner of the past as well.

She barely saw the streets slip by; barely saw the crowds on the drenched sidewalks, the posters, the hawkers and sellers, the bedraggled skyline of skyscrapers, each with tethered advertising balloons bobbing in the wind and their sides a maelstrom of pinprick-white lights star-bursting through the evening gloom, proclaiming the merits of some must-have, must-buy, must-show-off item.

Her eyes remained lost in another place and I wondered why.

Another H and S sign limped past. "Do not open beer bottles with your teeth when you are drunk. You will only realize this is a bad idea the next morning." Who were they kidding?

I recognized the building near it. It was by the Business Center for Not Answering Questions. I remembered how, at one time, it had been a popular institution, giving high-profile talks on the importance of not answering too many questions in business because it had been proven to cut into profits. It was rumored that if anyone ever tried to clarify anything they said, they simply ignored them.

Or sometimes they all put on hats and pretended to be French.

More buildings passed by, but the new architecture just looked like secondhand ideas served up cold, seeping disdain into the city. I didn't like it.

Finally we thumped through a gate and into a massive lot heaving with police drongles–some empty, and others disgorging people into the night.

The cop chewing gum opened the hood with a grunt, shoved my bag into my cuffed hands, and nodded. It was pouring rain as we climbed out and wove our way through the puddles and across the drenched lot that sparkled with reflected lights.

Head Hack Central was lit up with glowing red columns of light. The building was meant to look like it came from classical Greece, but the facade was more like a cross between a wedding cake and a nativity display.

I had been here as a cop.

As we walked through the massive worn doors and into a lobby, memories came at me, one after the other, like stones dropped in a still pool. But I ignored them all. There would be plenty of time to trawl the memories of this place and I wasn't interested in doing that yet. I had been traveling for what seemed like a decade, and right now I just needed to get out of here and find a bed.

We were led down a corridor lined with offices. The woman was taking it all in. It occurred to me she was looking for a way out, and I suddenly felt a frisson of pity for her. Now I understood why she had been caught up in her thoughts in the drongle.

She had something to hide.

Chapter Three

The use of the color red was restricted in New Seattle, because the cops held the franchise. That's why they carried small red truncheons and guns, because it was a marketing thing. I learned all this from a chubby cop who chattered good-naturedly as he left the two of us in a small temporary holding area, composed of a dozen seats enclosed by a small cage. He kept my bag, saying I could pick it up on the way out.

A few other people were already waiting under the glare of a harsh fluorescent light that doused the area with a particularly soulless sense of inhumanity. Across from me was a gaunt man, staring off at things only he could see. His limp-waisted appearance made it appear as though his body had been blown up without quite enough air, and his thin lips didn't seem as if they would have any words behind them. He saw me and smiled, and it creased up more of his face than expected. The girl paced slowly around, still taking in the layout, and I wondered if she would make a bolt for it when they took off our cuffs.

Then someone else was brought in, remonstrating fiercely with a cop. "But I have a license to drop melons," he was saying. His voice was thick with phlegm, and he dripped water from a blotchy raincoat.

"Sure you do," said the cop, shoving him through the gate and leaning his bulging shopping bag up against the desk.

"I do. I have it here. You want to see it?"

"There's no such thing as a license to drop ripe melons from the roofs of very high buildings," said the cop. "Make yourself comfortable. We'll call you."

"But I have license. Where's the thing?" He began to thumb through his raincoat pockets, pulling out a variety of dirty objects. "I got it from the State Department. It cost me fifty dollars. Hey–you see? Here!" He flourished a piece of paper and shoved it through the bars.

"You write this yourself?" said the cop, handing it back.

"No! It's a genuine license to drop ripe melons from the roof of tall buildings. Genuine! You haven't read it, have you? An official melon license. Ah, goddamn it. Cops!" He took the thing back, rammed it into his pocket, and sat down grouchily across from us. I could see a melon protruding from the top of his shopping bag by the main desk.

I sat back and closed my eyes, and realized the smell of disinfectant in this place hadn't changed at all. Another cascade of memories came at me, bright and clear.

Then a tiny voice filled me with a shiver, and it took me a moment to realize that it was someone whispering in my ear.

"They say there's another city like this one, but it is empty," it said, and I opened my eyes and turned.

It was an old man.

"What?" His deep blue eyes sparkled and then he leaned close to my ear again and whispered, "A place where there are no people. And you walk through and there's not a sound. Just the empty buildings. I've dreamed of it."

Descriere

Following his iconoclastic science fiction debut "Outrageous Fortune," Scott returns with a hilarious yet poignant stand-alone novel of love, loss, and itinerant appliances.