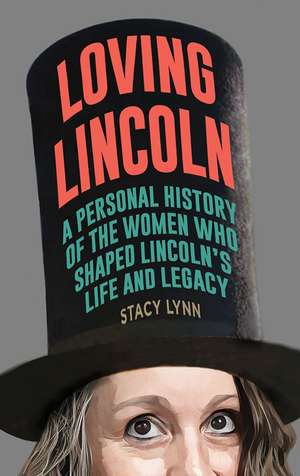

Loving Lincoln: A Personal History of the Women Who Shaped Lincoln's Life and Legacy: Illinois Lives

Autor Stacy Lynnen Limba Engleză Paperback – 2 iun 2025

Abraham Lincoln belongs to everybody. The women he interacted with helped forge the outstanding moral character of America's greatest president. This unique Abraham Lincoln biography features thirty historical and personal essays, and within them, the stories of more than ninety women, each with their own mini biographies in an appendix. Among them are Lincoln’s friends, clients, and extended family, as well as writers, artists, and—blurring the lines between history and memoir—author Stacy Lynn herself.

As a professional Lincoln scholar and editor, Lynn was often frustrated that male historians often overlooked Lincoln’s love for and friendship with women. Here, she posits a new paradigm—one that, instead of downplaying women, lifts up their interactions with Lincoln.

Lincoln understood the importance of the women in his life, and he put women’s wellbeing at the center of his personal, professional, and political ethos. He was loved by two strong pioneer mothers as well as sisters, friends, nieces, friends’ daughters, and his wife. He served women clients during his long legal career. As president, he met with women, dedicating time to hear their concerns despite the burdens of office. He replied to letters women wrote him. He believed in their capabilities and revolutionized the role of women in the workforce. After Lincoln’s death, women continued to shape his legacy. Mary Lincoln ensured his burial among friends, artist Vinnie Ream sculpted his statue in the US Capitol, and biographer Ida Tarbell provided a nuanced portrayal of his life. Harriet Monroe and Ruth Painter Randall further cemented his place in literature and history.

Lynn presents a fresh perspective on Lincoln, connecting his story to the stories of women and showcasing his kindness, sensitivity, and moral center. She explores how women shaped Lincoln’s inspirational legacy and pays homage to all the women who gave Lincoln to the world. Lynn’s unique blending of history, biography, and her own story reveals the ways in which an emotional connection to the historical figures one studies opens the door to richer human and historical understanding. By inviting readers to feel the past as well as read it, Lynn demonstrates that history matters most when it engages our minds and hearts.

Preț: 158.89 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 238

Preț estimativ în valută:

30.41€ • 33.02$ • 25.54£

30.41€ • 33.02$ • 25.54£

Carte nepublicată încă

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780809339679

ISBN-10: 0809339676

Pagini: 280

Ilustrații: 27

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.06 kg

Ediția:First Edition

Editura: Southern Illinois University Press

Colecția Southern Illinois University Press

Seria Illinois Lives

ISBN-10: 0809339676

Pagini: 280

Ilustrații: 27

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.06 kg

Ediția:First Edition

Editura: Southern Illinois University Press

Colecția Southern Illinois University Press

Seria Illinois Lives

Notă biografică

Stacy Lynn edited Abraham Lincoln’s papers for twenty-five years. She is the author or editor of four books, including Mary Lincoln: Southern Girl, Northern Woman. She is associate editor of the Jane Addams Papers.

Extras

Preface

I took my seat on the platform in a motel ballroom in Springfield, Illinois. My legs were wobbly. My stomach was rumbling because I had not eaten all day, my body too nervous for food in those early days of public speaking. It was one of my first historical conferences as a participant. My inexperience had set fire to my nerves, and my master’s degree in history from a small, public university was a thump of inadequacy in my head. I was an interloper, a young woman in heavy eyeliner among silver-haired scholars with PhDs and blazers with elbow patches. It was a month before I gained admission to the doctoral program in history at the University of Illinois. I lacked scholarly pedigree and confidence, and Lincoln Studies was unwelcoming to women.

I was, however, fast accumulating historical knowledge about the law and Abraham Lincoln as an assistant editor at the Lincoln Legal Papers Project. Founded in 1985 in Springfield to document Lincoln’s law practice, the Project had the imprimatur of the Abraham Lincoln Association, the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency, and the University of Illinois Springfield (UIS), which employed me and other staff editors. Our modest offices were in the Old State Capitol’s basement, but we were on the verge of becoming the Papers of Abraham Lincoln, a step that would increase not only the scope of our work but also our national exposure, staff, and grant funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the National Historical Publications and Records Commission, the State of Illinois, UIS, and private donors.

Despite the Project’s rising fortunes, my position was soft funded and precarious. In fact, I was an accidental editor of Lincoln’s papers, having fallen into an internship in 1992, which led to short-term contracts and then to a full-time position in 1996. When you only have a master’s degree in history, you cling to any employment in the field you can find, and my job at the Lincoln Papers provided a paycheck and health care for my young family. My salary reflected my status at the bottom of the Project’s hierarchy, and I did not expect to remain long term. I had two colleagues who encouraged me to stay the Lincoln course, but the director discouraged my application to doctoral programs and asked me to consider whether it was fair to my husband and two young daughters to take on such a challenge. He thought I was a mom with a history hobby. Fortunately, my husband and daughters cheered me on, and I possessed just enough audacity to apply to the University of Illinois, to which I was accepted. Doctoral work would prove to the doubters—and to myself—that I was serious about history and serious, too, about Lincoln. I planned to keep clinging to Abraham Lincoln as long as possible, but in March 2000 I was a nobody presenting a Lincoln paper far from groundbreaking at an obscure public history conference.

On the platform, I shuffled my notes. I picked at my bloody cuticles. I watched people arrive, the chattering hum in the room growing louder as they met friends and found seats.

And then Abraham Lincoln arrived, doffing his stovepipe hat.

The tension in my jaw released into a smile.

A second Abraham Lincoln entered the room. Then a third. Then a fourth. Four bearded men dressed in black dusters, deliberately disheveled cravats, and versions of Lincoln’s iconic hat were taking their seats in my audience. Four Abraham Lincolns. At a small history conference in Lincoln’s hometown. Attending a session on the topic of Abraham Lincoln’s law practice.

Nearly eighty years after Lincoln settled in Springfield, the wistful poet and fellow Springfieldian Vachel Lindsay wrote: “Abraham Lincoln walks at midnight … a bronzed, lank man!” There I was eighty-six years after Lindsay’s poem aware of Lincoln’s presence, too; although not as an ethereal one mourning the tragedy of world war, but as a corporeal one in the form of grown men in costumes.

I had lived in Springfield long enough to understand that Abraham Lincoln was more than a favorite son and famous tether to the past, more engrained in the city’s identity than the imposing state capitol building and its role as the seat of Illinois government. I often saw these living Lincolns. They were part of the cityscape, ubiquitous in restaurants and shops and on the plaza surrounding the Old State Capitol during fall festivals, art fairs, and conventions. They were frequent participants of popular public events at the Lincoln Home, the Lincoln Tomb, and the Lincoln and Herndon Law Office.

Unlike the real Lincoln when he walked Springfields’ clapboard sidewalks, these Lincoln presenters always have beards, although they are not always six feet and four inches. I smiled at those four Lincolns in my audience as I evaluated their relative Lincoln-ness. One of the four Lincolns looked taller than the real Lincoln and one much shorter. One looked nothing at all like Lincoln beyond his costume. And one I recognized as a locally famous Mr. Lincoln. Seeing Lincoln on the streets was normal but seeing four Lincolns in a history-conference audience felt ridiculous. The absurdity, however, eased the tensions in my muscles, calmed my public-speaking anxiety, and made me fall in love with my professional life.

Oh, no. I have caught the Lincoln bug and there is no cure for it.

I had tried to resist the lure of Mr. Lincoln in the face of my tentative position at the Lincoln Papers, but just like Mary Todd I succumbed to Lincoln’s charms. I had fallen into Lincoln Studies like Alice down the rabbit hole. What a wonderful world I found there. I could no longer deny the glorious coincidence of my historical circumstances either: I was a budding historian living in an 1860s house on Lincoln Avenue in Lincoln’s Springfield, with one daughter attending Lincoln School and the other attending a school named for Lincoln’s friend Jesse K. Dubois. I was working for a project collecting and editing Lincoln’s legal papers in the building where Lincoln delivered his House Divided speech. And so, therefore and to wit, with four Abraham Lincolns as my witnesses, I hitched my scholarly wagon to Abraham Lincoln and never looked back.

Five months later, I was a doctoral student at the University of Illinois in the history department made famous by Lincoln scholar James G. Randall. I wrote a dissertation in legal history with Lincoln’s law practice at its center, and I became a Lincoln scholar. My plan to stay the Lincoln course, which I reaffirmed with the completion of my PhD in 2007 and my rise to associate editor and assistant director of the Lincoln Papers in 2009 offered intellectual rewards. I was a coeditor of the groundbreaking digital edition The Law Practice of Abraham Lincoln and the award-winning, four-volume letterpress edition The Papers of Abraham Lincoln: Legal Documents and Cases. I was a founding editor of the Papers of Abraham Lincoln, a project to digitize and transcribe Lincoln’s documents from the Illinois legislature to the presidency.

Studying Lincoln, editing his papers, engaged in innovative work in digital humanities was a dream profession, providing a bevy of research topics and affording opportunities for writing, travel, and engagements I could never have imagined. During my tenure as a Lincoln editor, I published a book based on my dissertation and a Mary Lincoln biography. I wrote dozens of essays and book reviews, spoke on the stage at Ford’s Theatre, appeared in two Lincoln documentaries, and joined the board of the prestigious Abraham Lincoln Institute. Along my Lincoln path, I also assembled a brilliant collection of Lincoln folk, people who possess a ceaseless intellectual curiosity about Lincoln but who also find joy in the absurdities dancing around the edges of scholarship, people who, like me, have Lincoln bobbleheads on their bookcases next to full sets of The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln.

I was one lucky Lincoln duck, privileged not only to be engaged in the niche field of historical editing, but to digitize Lincoln documents at the Copley Library in La Jolla, California, the University of Maine in Bangor, and in more than 100 repositories and private collections in between. I conducted research at many institutions famous for their Lincoln collections, including the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library, the Library of Congress, the National Archives, the Illinois State Archives, and special collections libraries at Harvard, Yale, and Indiana University. I scanned one of the five copies of the Gettysburg Address, identified letter fragments found in the walls of the Lincoln Home, oversaw the complicated digitization of a 25-foot-long petition to President Lincoln at the New-York Historical Society, and scanned the Lincoln legal documents owned by former Illinois Governor Jim Thompson, while chatting with Big Jim in his Chicago law office overlooking Lake Michigan. At the time I left the Papers of Abraham Lincoln in November 2016, my colleagues and I in Springfield and Washington had digitized 102,000 Lincoln documents, in addition to the more than 90,000 legal documents we had already published.

Despite thrilling discoveries, fulfilling work, and gratitude for earning a salary with benefits to study Abraham Lincoln, there was a dark side to my Lincoln journey. Like Lincoln’s own melancholy, there was pain below the surface of my joy and good fortune. My struggle was, in part, rooted in my own insecurities. Unattached to an academic department, I always felt outranked by tenured professors who published books and appeared on television. I felt trapped between academic and public history. Even though I was suited to editing work, I pined for a professorship, a job far easier to explain than scholarly editing. I knew editing Lincoln’s papers made me a Lincoln scholar. But would Lincoln Studies ever accept me as one?

Not long after making Abraham Lincoln my historical muse, I traveled to St. Louis for the Organization of American Historians annual meeting to give a paper on digital historical editing. At an evening reception, a colleague introduced me to a prominent scholar. The man did not say hello or extend his hand in greeting. Instead, he leaned back, his chin resting on his chest, and ogled me, up and down, avoiding my eyes. Then, in a booming voice, he said: “You must be the new Lincoln Legal eye candy.” I should not have been shocked, because his reputation preceded him. In fact, I had prepared myself to endure something gross. Yet nothing could have prepared me for the crestfallen slump of my ego and the humiliation burning on my cheeks. His comment was not half of the offense, however. While I stood there pursing my lips to contain my scream, three male colleagues standing with me in that god-awful cocktail circle, sipped their drinks in awkward silence.

I was silent, too. I was having a conversation in my head with Abraham Lincoln. He was horrified on my behalf. He was on my side, even if no one, not even me, would offer a defense. Lincoln was worth this little indigestion, I said to myself, and I believed it. I was heartbroken but not broken, because I believed in Abraham Lincoln.

I am the scholar I am today because of my determination in the face of disrespect and rejection, but the indignities were painful. Another formative affront came a few years after the wretched cocktail party from an older man I liked despite his arrogance and abrasive personality. He was brilliant and funny, and I enjoyed talking with him. In a convention center hallway between sessions of a history conference, we were talking when he stopped short, looked at me with a furrowed brow, and asked: “Do you think anyone takes you seriously in such heavy eye makeup?”

My mind raced to the bathroom mirror, to the morning hours when I had painted on my eyeliner, the only makeup I have ever applied with care.

No. Same as always. Less, in fact, now, because it is hot, and I am sweating.

I looked back at this man, standing there in his tweed blazer with elbow patches. I was in my mid-thirties, a mother, a grown-up professional woman with four semesters of cut-throat doctoral seminars under my belt, but I was shocked, once again, into silence. I did not respond, channeling not Lincoln this time but my mother.

If you don’t have anything nice to say, keep your mouth shut.

In my head, I had my own questions.

Do you wonder if the curated stubble or combovers of my male colleagues make them suspect? Do you say such things aloud to men?

[end of excerpt]

I took my seat on the platform in a motel ballroom in Springfield, Illinois. My legs were wobbly. My stomach was rumbling because I had not eaten all day, my body too nervous for food in those early days of public speaking. It was one of my first historical conferences as a participant. My inexperience had set fire to my nerves, and my master’s degree in history from a small, public university was a thump of inadequacy in my head. I was an interloper, a young woman in heavy eyeliner among silver-haired scholars with PhDs and blazers with elbow patches. It was a month before I gained admission to the doctoral program in history at the University of Illinois. I lacked scholarly pedigree and confidence, and Lincoln Studies was unwelcoming to women.

I was, however, fast accumulating historical knowledge about the law and Abraham Lincoln as an assistant editor at the Lincoln Legal Papers Project. Founded in 1985 in Springfield to document Lincoln’s law practice, the Project had the imprimatur of the Abraham Lincoln Association, the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency, and the University of Illinois Springfield (UIS), which employed me and other staff editors. Our modest offices were in the Old State Capitol’s basement, but we were on the verge of becoming the Papers of Abraham Lincoln, a step that would increase not only the scope of our work but also our national exposure, staff, and grant funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the National Historical Publications and Records Commission, the State of Illinois, UIS, and private donors.

Despite the Project’s rising fortunes, my position was soft funded and precarious. In fact, I was an accidental editor of Lincoln’s papers, having fallen into an internship in 1992, which led to short-term contracts and then to a full-time position in 1996. When you only have a master’s degree in history, you cling to any employment in the field you can find, and my job at the Lincoln Papers provided a paycheck and health care for my young family. My salary reflected my status at the bottom of the Project’s hierarchy, and I did not expect to remain long term. I had two colleagues who encouraged me to stay the Lincoln course, but the director discouraged my application to doctoral programs and asked me to consider whether it was fair to my husband and two young daughters to take on such a challenge. He thought I was a mom with a history hobby. Fortunately, my husband and daughters cheered me on, and I possessed just enough audacity to apply to the University of Illinois, to which I was accepted. Doctoral work would prove to the doubters—and to myself—that I was serious about history and serious, too, about Lincoln. I planned to keep clinging to Abraham Lincoln as long as possible, but in March 2000 I was a nobody presenting a Lincoln paper far from groundbreaking at an obscure public history conference.

On the platform, I shuffled my notes. I picked at my bloody cuticles. I watched people arrive, the chattering hum in the room growing louder as they met friends and found seats.

And then Abraham Lincoln arrived, doffing his stovepipe hat.

The tension in my jaw released into a smile.

A second Abraham Lincoln entered the room. Then a third. Then a fourth. Four bearded men dressed in black dusters, deliberately disheveled cravats, and versions of Lincoln’s iconic hat were taking their seats in my audience. Four Abraham Lincolns. At a small history conference in Lincoln’s hometown. Attending a session on the topic of Abraham Lincoln’s law practice.

Nearly eighty years after Lincoln settled in Springfield, the wistful poet and fellow Springfieldian Vachel Lindsay wrote: “Abraham Lincoln walks at midnight … a bronzed, lank man!” There I was eighty-six years after Lindsay’s poem aware of Lincoln’s presence, too; although not as an ethereal one mourning the tragedy of world war, but as a corporeal one in the form of grown men in costumes.

I had lived in Springfield long enough to understand that Abraham Lincoln was more than a favorite son and famous tether to the past, more engrained in the city’s identity than the imposing state capitol building and its role as the seat of Illinois government. I often saw these living Lincolns. They were part of the cityscape, ubiquitous in restaurants and shops and on the plaza surrounding the Old State Capitol during fall festivals, art fairs, and conventions. They were frequent participants of popular public events at the Lincoln Home, the Lincoln Tomb, and the Lincoln and Herndon Law Office.

Unlike the real Lincoln when he walked Springfields’ clapboard sidewalks, these Lincoln presenters always have beards, although they are not always six feet and four inches. I smiled at those four Lincolns in my audience as I evaluated their relative Lincoln-ness. One of the four Lincolns looked taller than the real Lincoln and one much shorter. One looked nothing at all like Lincoln beyond his costume. And one I recognized as a locally famous Mr. Lincoln. Seeing Lincoln on the streets was normal but seeing four Lincolns in a history-conference audience felt ridiculous. The absurdity, however, eased the tensions in my muscles, calmed my public-speaking anxiety, and made me fall in love with my professional life.

Oh, no. I have caught the Lincoln bug and there is no cure for it.

I had tried to resist the lure of Mr. Lincoln in the face of my tentative position at the Lincoln Papers, but just like Mary Todd I succumbed to Lincoln’s charms. I had fallen into Lincoln Studies like Alice down the rabbit hole. What a wonderful world I found there. I could no longer deny the glorious coincidence of my historical circumstances either: I was a budding historian living in an 1860s house on Lincoln Avenue in Lincoln’s Springfield, with one daughter attending Lincoln School and the other attending a school named for Lincoln’s friend Jesse K. Dubois. I was working for a project collecting and editing Lincoln’s legal papers in the building where Lincoln delivered his House Divided speech. And so, therefore and to wit, with four Abraham Lincolns as my witnesses, I hitched my scholarly wagon to Abraham Lincoln and never looked back.

Five months later, I was a doctoral student at the University of Illinois in the history department made famous by Lincoln scholar James G. Randall. I wrote a dissertation in legal history with Lincoln’s law practice at its center, and I became a Lincoln scholar. My plan to stay the Lincoln course, which I reaffirmed with the completion of my PhD in 2007 and my rise to associate editor and assistant director of the Lincoln Papers in 2009 offered intellectual rewards. I was a coeditor of the groundbreaking digital edition The Law Practice of Abraham Lincoln and the award-winning, four-volume letterpress edition The Papers of Abraham Lincoln: Legal Documents and Cases. I was a founding editor of the Papers of Abraham Lincoln, a project to digitize and transcribe Lincoln’s documents from the Illinois legislature to the presidency.

Studying Lincoln, editing his papers, engaged in innovative work in digital humanities was a dream profession, providing a bevy of research topics and affording opportunities for writing, travel, and engagements I could never have imagined. During my tenure as a Lincoln editor, I published a book based on my dissertation and a Mary Lincoln biography. I wrote dozens of essays and book reviews, spoke on the stage at Ford’s Theatre, appeared in two Lincoln documentaries, and joined the board of the prestigious Abraham Lincoln Institute. Along my Lincoln path, I also assembled a brilliant collection of Lincoln folk, people who possess a ceaseless intellectual curiosity about Lincoln but who also find joy in the absurdities dancing around the edges of scholarship, people who, like me, have Lincoln bobbleheads on their bookcases next to full sets of The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln.

I was one lucky Lincoln duck, privileged not only to be engaged in the niche field of historical editing, but to digitize Lincoln documents at the Copley Library in La Jolla, California, the University of Maine in Bangor, and in more than 100 repositories and private collections in between. I conducted research at many institutions famous for their Lincoln collections, including the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library, the Library of Congress, the National Archives, the Illinois State Archives, and special collections libraries at Harvard, Yale, and Indiana University. I scanned one of the five copies of the Gettysburg Address, identified letter fragments found in the walls of the Lincoln Home, oversaw the complicated digitization of a 25-foot-long petition to President Lincoln at the New-York Historical Society, and scanned the Lincoln legal documents owned by former Illinois Governor Jim Thompson, while chatting with Big Jim in his Chicago law office overlooking Lake Michigan. At the time I left the Papers of Abraham Lincoln in November 2016, my colleagues and I in Springfield and Washington had digitized 102,000 Lincoln documents, in addition to the more than 90,000 legal documents we had already published.

Despite thrilling discoveries, fulfilling work, and gratitude for earning a salary with benefits to study Abraham Lincoln, there was a dark side to my Lincoln journey. Like Lincoln’s own melancholy, there was pain below the surface of my joy and good fortune. My struggle was, in part, rooted in my own insecurities. Unattached to an academic department, I always felt outranked by tenured professors who published books and appeared on television. I felt trapped between academic and public history. Even though I was suited to editing work, I pined for a professorship, a job far easier to explain than scholarly editing. I knew editing Lincoln’s papers made me a Lincoln scholar. But would Lincoln Studies ever accept me as one?

Not long after making Abraham Lincoln my historical muse, I traveled to St. Louis for the Organization of American Historians annual meeting to give a paper on digital historical editing. At an evening reception, a colleague introduced me to a prominent scholar. The man did not say hello or extend his hand in greeting. Instead, he leaned back, his chin resting on his chest, and ogled me, up and down, avoiding my eyes. Then, in a booming voice, he said: “You must be the new Lincoln Legal eye candy.” I should not have been shocked, because his reputation preceded him. In fact, I had prepared myself to endure something gross. Yet nothing could have prepared me for the crestfallen slump of my ego and the humiliation burning on my cheeks. His comment was not half of the offense, however. While I stood there pursing my lips to contain my scream, three male colleagues standing with me in that god-awful cocktail circle, sipped their drinks in awkward silence.

I was silent, too. I was having a conversation in my head with Abraham Lincoln. He was horrified on my behalf. He was on my side, even if no one, not even me, would offer a defense. Lincoln was worth this little indigestion, I said to myself, and I believed it. I was heartbroken but not broken, because I believed in Abraham Lincoln.

I am the scholar I am today because of my determination in the face of disrespect and rejection, but the indignities were painful. Another formative affront came a few years after the wretched cocktail party from an older man I liked despite his arrogance and abrasive personality. He was brilliant and funny, and I enjoyed talking with him. In a convention center hallway between sessions of a history conference, we were talking when he stopped short, looked at me with a furrowed brow, and asked: “Do you think anyone takes you seriously in such heavy eye makeup?”

My mind raced to the bathroom mirror, to the morning hours when I had painted on my eyeliner, the only makeup I have ever applied with care.

No. Same as always. Less, in fact, now, because it is hot, and I am sweating.

I looked back at this man, standing there in his tweed blazer with elbow patches. I was in my mid-thirties, a mother, a grown-up professional woman with four semesters of cut-throat doctoral seminars under my belt, but I was shocked, once again, into silence. I did not respond, channeling not Lincoln this time but my mother.

If you don’t have anything nice to say, keep your mouth shut.

In my head, I had my own questions.

Do you wonder if the curated stubble or combovers of my male colleagues make them suspect? Do you say such things aloud to men?

[end of excerpt]

Recenzii

“Lincoln lovers will recognize themselves in Lynn. The disinterested will become swept up in her—and his female contemporaries’—view of Lincoln as a genuinely compassionate man who loved and respected women.”—Leigh Fought, author of Women in the World of Frederick Douglass

“Written with a unique blend of passion, personal perspective, and historical insight, Loving Lincoln shares Stacy Lynn’s journey in the world of Lincoln Studies while exploring the stories the women who helped shape Abraham Lincoln’s life and legacy. Told through concise, well-crafted chapters, readers will encounter a new take on an understudied aspect of Lincoln’s life.”—Jonathan W. White, Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize–winning author of A House Built by Slaves: African American Visitors to the Lincoln White House

“Loving Lincoln is a thoroughly researched, exquisite account of the relationships Abraham Lincoln had with the myriad women with whom he shared meaningful experiences and fills a critical void in the expansive Lincoln canon. But what makes Loving Lincoln extraordinary is the very human way that Stacy Lynn weaves together her own becoming—as editor and scholar, grieving mother and bold historian—with the stories of the women who loved and nurtured Abraham Lincoln. Lynn approaches this work as only she can—with an unparalleled command of the Lincoln Papers and a profound personal and professional understanding of what makes Abraham Lincoln worthy of our reverence.”—Callie Hawkins, CEO and executive director, President Lincoln’s Cottage

“Written with a unique blend of passion, personal perspective, and historical insight, Loving Lincoln shares Stacy Lynn’s journey in the world of Lincoln Studies while exploring the stories the women who helped shape Abraham Lincoln’s life and legacy. Told through concise, well-crafted chapters, readers will encounter a new take on an understudied aspect of Lincoln’s life.”—Jonathan W. White, Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize–winning author of A House Built by Slaves: African American Visitors to the Lincoln White House

“Loving Lincoln is a thoroughly researched, exquisite account of the relationships Abraham Lincoln had with the myriad women with whom he shared meaningful experiences and fills a critical void in the expansive Lincoln canon. But what makes Loving Lincoln extraordinary is the very human way that Stacy Lynn weaves together her own becoming—as editor and scholar, grieving mother and bold historian—with the stories of the women who loved and nurtured Abraham Lincoln. Lynn approaches this work as only she can—with an unparalleled command of the Lincoln Papers and a profound personal and professional understanding of what makes Abraham Lincoln worthy of our reverence.”—Callie Hawkins, CEO and executive director, President Lincoln’s Cottage

Descriere

This biography of Abraham Lincoln, told through the stories of the women in his life and work, is also the story of the author’s professional and personal relationship with Lincoln as a scholar and editor of his papers and as a woman who has drawn inspiration and solace from his life and his legacy.