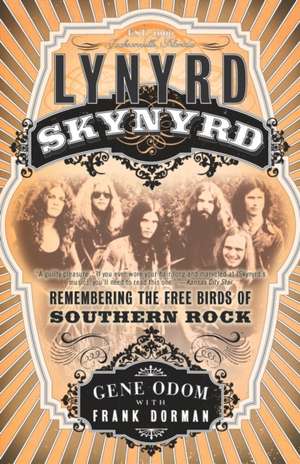

Lynyrd Skynyrd: Remembering the Free Birds of Southern Rock

Autor Gene Odom Frank Dormanen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 sep 2003

In the summer of 1964 Jacksonville, Florida teenager Ronnie Van Zant and some of his friends hatched the idea of forming a band to play covers of the Rolling Stones, Beatles, Yardbirds and the country and blues-rock music they had grown to love. Naming their band after Leonard Skinner, the gym teacher at Robert E. Lee Senior High School who constantly badgered the long-haired aspiring musicians to get haircuts, they were soon playing gigs at parties, and bars throughout the South. During the next decade Lynyrd Skynyrd grew into the most critically acclaimed and commercially successful of the rock bands to emerge from the South since the Allman Brothers. Their hits “Free Bird” and “Sweet Home Alabama” became classics. Then, at the height of its popularlity in 1977, the band was struck with tragedy --a plane crash that killed Ronnie Van Zant and two other band members.

Lynyrd Skynyrd: Remembering the Free Birds of Southern Rock is an intimate chronicle of the band from its earliest days through the plane crash and its aftermath, to its rebirth and current status as an enduring cult favorite. From his behind-the-scenes perspective as Ronnie Van Zant’s lifelong friend and frequent member of the band’s entourage who was also aboard the plane on that fateful flight, Gene Odom reveals the unique synthesis of blues/country rock and songwriting talent, relentless drive, rebellious Southern swagger and down-to-earth sensibility that brought the band together and made it a defining and hugely popular Southern rock band -- as well as the destructive forces that tore it apart. Illustrated throughout with rare photos, Odom traces the band’s rise to fame and shares personal stories that bring to life the band’s journey.

For the fans who have purchased a cumulative 35 million copies of Lynyrd Skynyrd’s albums and continue to pack concerts today, Lynyrd Skynyrd is a celebration of an immortal American band.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 146.93 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 220

Preț estimativ în valută:

28.12€ • 30.06$ • 23.44£

28.12€ • 30.06$ • 23.44£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780767910279

ISBN-10: 0767910273

Pagini: 270

Ilustrații: 75 PHOTOS THROUGHOUT

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

ISBN-10: 0767910273

Pagini: 270

Ilustrații: 75 PHOTOS THROUGHOUT

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

Notă biografică

Gene Odom grew up with the original members of the Lynyrd Skynyrd band, later serving as their security manager. He now lives in Jacksonville, Florida. Journalist Frank Dorman lives in Richmond, Virginia.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Chapter 1

Redneck

Early in the fall of 1976, the world's top rock and roll artists gathered in Hollywood to celebrate their success. The occasion was Don Kirschner's Annual Rock Awards, a nationally televised show to honor the best of the artists who had appeared on Kirschner's weekly television show, Rock Concert.

Practically everyone who was anyone in the rock music business had come to the grand old, flamingo pink Beverly Hills Hotel that evening, along with a smattering of TV and movie stars whose presence seemed almost obligatory in a town that once had been ruled by film. Among the musical set were Rod Stewart, flanked by a flock of beautiful women, Peter Frampton, whose Frampton Comes Alive album would sell eight million copies that year, and the rising songstress Patti LaBelle. Few and barely distinguishable by comparison, the stars of film and television included twelve-year-old Tatum O'Neal, an Oscar winner for her role in the movie Paper Moon; and sixteen-year-old Mackenzie Phillips, who had appeared in American Graffiti.

In the 1970s, the billboards that towered above Sunset Boulevard promoted record albums, not movies, and the biggest cinema star in the building that day wasn't even there for the show; she was having dinner. Hoping to see the luminaries of rock step from their limos and stroll through the entrance of the world-famous hotel, a large group of spectators was surprised to see her emerge from the lobby. Walking slowly but proudly on the arm of a younger man, this living fossil from Hollywood's golden age was the once glamorous Mae West, whose eighty-four zestful years had so distorted her face that no one would have recognized her if hotel staff hadn't announced her name. Minutes later, in the starkest of contrasts came the arrival of one of the greatest divas of the day, the dazzling, ever-radiant Diana Ross, who held the crowd's gaze as if she were actual royalty. Aglow in the warmth from a score of popping flashbulbs, she responded through bright, beaming eyes and her famous, self-conscious smile, seemingly confident that everyone had come just to see her.

Inside the hotel auditorium, where admission was by invitation only, hundreds of formally attired guests settled into their seats to hear some of the year's top performing acts. The emcee was Alice Cooper, who started things off with a well-rehearsed temper tantrum that segued into a strange, wonderfully choreographed number in which dancers dressed as spiders moved across the stage while Cooper's band played. It was big-time show business at its creative best. The aristocracy of the recording industry were being entertained, having come to honor the year's top performers, the creme de la creme, the ones who had sold the most records. Only in Technicolor dreams could you conceive of a Cinderella setting more unlikely than was set that night for a good ol' boy from Jacksonville, Florida. Wearing a smile as wide as a Southern drawl as he walked toward center stage, Leon Wilkeson, bass guitar player for the Lynyrd Skynyrd band, accepted the Golden Achievement award for what truly was a remarkable level of accomplishment for a bunch of musical misfits. It was a moment filled with irony.

Leon always enjoyed wearing odd hats, but for this gala affair he'd chosen an entire ensemble, and I'm sure that Hollywood's smart set wondered how he'd managed to get past the hotel doorman in the godawful get-up he wore. It was a tuxedo, but it wasn't the traditional James Bond look. The pants and jacket were the customary flat black, but cut with a western flair. The shirt was appropriately white but ruffled from neck to navel. And if that weren't enough of a fashion faux pas in this discerning crowd of sophisticates, all dressed to the nines, Leon added his own fanciful touch, a white cowboy hat and boots, and a wide leather belt with a pair of pearl-handled pistols in cream-colored holsters. These were unexpected accessories for a musician from a band that didn't perform Western tunes, especially when one of their top hits, "Saturday Night Special," is still the most strongly worded anti-handgun pop song ever written.

But regardless of how anyone may have felt about Leon's attire that evening, it was decidedly more fitting than his usual garb; besides, show business people can wear whatever they want, and he was just having fun. In fact, after the show he danced with Mae West. Leon's outfit simply affirmed the Southern maxim: you can take the boy out of the country, but you can't take the country out of the boy. That's a nice way to say what is often expressed in a single word, a word someone uttered quietly in the back of the auditorium when Leon rose to claim the award.

"Redneck."

For anyone who doesn't understand what a redneck is, I should explain. The term originated before the turn of the last century, when most Americans worked on farms and got sunburned necks from being outdoors all day. City dwellers tended to look down on uncultured country folks, and the label was custom-made. If you call a man a redneck today, you're also calling him ignorant, but that "ain't no big thing" if you're a redneck, too. In that case, you're both just good ol' boys wherever you live in this country, although a Southern drawl will usually leave no doubt. Jacksonville, Florida, was where the original Lynyrd Skynyrd band members grew up, and most of its residents' forebears had moved there from the rural areas of Northeast Florida and Southeast Georgia. And for Jacksonville, you didn't get any more country than the Westside.

Despite the magic of the moment when he stood on that stage in Hollywood, Leon was still just a redneck from the Westside of Jacksonville, Florida, and he never pretended to be otherwise. I'm the same way, and so was my best friend, Ronnie Van Zant, the founding father, chief songwriter and singer, and undisputed leader of Lynyrd Skynyrd. Ronnie had asked Leon to accept the award that night at the Beverly Hills Hotel because Ronnie avoided the limelight when he wasn't on stage, and besides, getting dressed up wasn't his style, not even for a prestigious award. For Ronnie, it was jeans and a T-shirt and maybe a hat, unless it was cold, and that's all it would ever be.

To understand Lynyrd Skynyrd, you have to understand Ronnie Van Zant, who, at the peak of his success, was still the same person he was when he started out. Except for his extraordinary talent and the musical skills of the boys in the band, all of us and the people we grew up with were average rednecks. Like the rest of the folks who lived in our part of town, it was manual labor that put bread on the table, just as it had for every other generation before us. Ronnie's father, Lacy Van Zant, made his living hauling goods up and down the East Coast in a big rig truck, and his mother, Marion Virginia "Sister" Hicks Van Zant, worked nights in a donut shop. Her grandfather had called her "Sister" as a child, and the nickname stuck. Lacy and Sister met near the end of the Second World War when he was home on leave from the U.S. Navy and she was just fifteen. They started dating when he left the service two years later, and one of their favorite outings was sitting in a car listening to the radio and singing along with the music. After a year-long courtship, Lacy and Marion began a marriage that would last fifty-three years, and together they would raise six children: the oldest was Jo Anne, Lacy's daughter from a previous marriage, followed by Ronnie, Donnie, Marlene, Darlene, and Johnny.

Lacy was always a good provider, but Sister was the glue that held the family together, especially with Lacy out on the road so much as a truck driver. Sister was a friendly person, generous with everyone she met, but she had a firm side, too, and she was never shy about standing up for what she felt was right, especially if it involved her family. Their house was always open to everybody in the neighborhood, and anyone who ever visited the Van Zants never failed to notice the genuine respect the children had for their parents, and the politeness their kids always showed for each other and for other people.

Lacy and Sister made their home a happy place for their children to grow up in. It was a close, loving family in which the kids were encouraged to enjoy life, to be happy about themselves as individuals, to be proud of who they were in spite of their humble station in life, and to live the American dream without being afraid to fail. It was in this nurturing environment that Ronnie developed his one great dream and all of the confidence he would ever need. The boy loved both of his parents, and as the oldest son of a man who let him be himself, he revered his father. Lacy stressed the value of education, and Ronnie tried hard to be a good student, serving on the school safety patrol in the sixth grade, and sometimes making the honor roll in his upper grades. But just a few credits short of finishing, he withdrew from school toward the end of his senior year.

Leaving high school was a decision Ronnie always regretted, and later in life he confessed that, despite his success, he felt he had failed to live up to his father's expectations. This wasn't true, of course, because Lacy's love for his son was boundless, and yet this feeling followed Ronnie for the rest of his life. It drove him to succeed, and even after he'd done that, it drove him to excel. Many years later, Ronnie told a reporter, "All I can preach is school. That's where power lies, . . . If I can come out of [Shantytown], you can do it. I made a bad mistake. You gotta have education." He'd put platinum record albums on his father's wall, "but never a diploma," he said.

Ronald Wayne Van Zant was born January 15, 1948, in Jacksonville, Florida, and he lived near the outskirts of town on the city's Westside. The Van Zants' home was at the corner of Mull Street and Woodcrest Road. I lived on Mull Street just a few houses away, in a rough, blue-collar area that Ronnie called "Shantytown." He'd heard it called that by the mother of one of his friends, Jim Daniel, who lived in a different neighborhood. Ronnie found it amusing at the time, but the truth was clear to see. The houses were simple structures built mostly of concrete block or wood. Some had missing windows and doors, and some had no electricity. Most streets were paved, but there were dirt roads, too, and one of them distinguished our neighborhood in a way that only a redneck could appreciate. Not really a road, it was a racetrack; and if there is one sport that rednecks enjoy more than all the rest it's stock car racing. Every Saturday night and on many a Sunday afternoon this oval-shaped circle of sand became redneck heaven, and in our neighborhood, if you weren't at the races you felt them anyway, their thunderous roar so loud it rattled windows and smothered conversation in every house. Just three blocks from where Ronnie and I lived, at the corner of Ellis Road and Plymouth Street, Jacksonville's Speedway Park was a metaphor for where our lives would lead: most of us would ride in a circle going nowhere while one of us rode to glory.

For the biggest races at Speedway Park, more than six thousand people would pack the place to capacity, filling the wooden grandstands, the pits, and the infield. Everyone who sat in the bleachers knew they'd be showered with dirt when the cars went past, even in the top rows. But the dirt hardly ever reached Ronnie, our friends, and me, because whatever the admission price was, we couldn't afford it. We watched the races from just outside the fence, perched in the tops of the trees that circled the track. Some races we didn't watch, but we often went there anyway, hoping for a chance to make a little money. Every once in a while a tire would come flying over the fence, and whoever grabbed it first would try to hide it, scheming to sell it later to one of the race car owners, but not to the one who'd lost it.

Few people know it, but Ronnie wasn't the first major recording artist from Jacksonville to watch the races from outside the fence at Speedway Park. Charles Eugene "Pat" Boone, whose parents had hoped to name their first child "Patricia," was born in Jacksonville in 1934 and went on to sell more records during the 1960s than everyone but Elvis Presley. A descendant of Daniel Boone, he appeared in a number of hit movies, including State Fair and Journey to the Center of the Earth; he had fifteen hits in the Top 10, including "April Love" and "Love Letters in the Sand," which stayed on the charts for thirty-four weeks; and he still holds Billboard magazine's all-time record of two hundred consecutive weeks on the charts with more than one song. Pat Boone was two years old when his family moved from his mother's hometown to Nashville, Tennessee, but on numerous occasions over a period of many years, while visiting relatives in Florida the Boones enjoyed going to Speedway Park. Although they could have purchased tickets (Boone's father was an architect/builder; his mother was a registered nurse), like so many others they preferred viewing the action close-up where they could feel the ground shake as the cars roared past, so they sat in custom-made "bleachers" set up in the beds of pickup trucks at the start of the back straightaway.

Speedway Park was the fastest half-mile dirt track in the nation because it was a "big half-mile." Measured on the inside, it was five-eighths of a mile around, which meant that drivers could reach higher speeds than they could manage on a standard half-mile course. Drawing thousands of fans from all over northeast Florida and southeast Georgia, Speedway Park was part of the National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing's (NASCAR) Grand National circuit, which later became the Winston Cup series. All of the famous drivers raced there. Richard Petty, Tiny Lund, Junior Johnson, Fireball Roberts, Bobby and Donnie Allison, David Ezell, Cale Yarborough, Lee Roy Yarbrough, and Wendell Scott.

One of the nation's top drivers, Lee Roy Yarbrough had his best year in 1969 by winning the Daytona 500 and two other major events. Yarbrough lived in our neighborhood, one block from the track, and starting in the early '60s Ronnie and I used to hang around while he worked on his car in the yard beside his house. We were probably ten years younger than Lee Roy, but he seemed to enjoy our company. Lee Roy was a real-life local sports hero for us, and as Ronnie got older and he began to think about his future, he used to say that he was going to be the most famous person to come out of Jacksonville since Lee Roy Yarbrough.

From the Hardcover edition.

Redneck

Early in the fall of 1976, the world's top rock and roll artists gathered in Hollywood to celebrate their success. The occasion was Don Kirschner's Annual Rock Awards, a nationally televised show to honor the best of the artists who had appeared on Kirschner's weekly television show, Rock Concert.

Practically everyone who was anyone in the rock music business had come to the grand old, flamingo pink Beverly Hills Hotel that evening, along with a smattering of TV and movie stars whose presence seemed almost obligatory in a town that once had been ruled by film. Among the musical set were Rod Stewart, flanked by a flock of beautiful women, Peter Frampton, whose Frampton Comes Alive album would sell eight million copies that year, and the rising songstress Patti LaBelle. Few and barely distinguishable by comparison, the stars of film and television included twelve-year-old Tatum O'Neal, an Oscar winner for her role in the movie Paper Moon; and sixteen-year-old Mackenzie Phillips, who had appeared in American Graffiti.

In the 1970s, the billboards that towered above Sunset Boulevard promoted record albums, not movies, and the biggest cinema star in the building that day wasn't even there for the show; she was having dinner. Hoping to see the luminaries of rock step from their limos and stroll through the entrance of the world-famous hotel, a large group of spectators was surprised to see her emerge from the lobby. Walking slowly but proudly on the arm of a younger man, this living fossil from Hollywood's golden age was the once glamorous Mae West, whose eighty-four zestful years had so distorted her face that no one would have recognized her if hotel staff hadn't announced her name. Minutes later, in the starkest of contrasts came the arrival of one of the greatest divas of the day, the dazzling, ever-radiant Diana Ross, who held the crowd's gaze as if she were actual royalty. Aglow in the warmth from a score of popping flashbulbs, she responded through bright, beaming eyes and her famous, self-conscious smile, seemingly confident that everyone had come just to see her.

Inside the hotel auditorium, where admission was by invitation only, hundreds of formally attired guests settled into their seats to hear some of the year's top performing acts. The emcee was Alice Cooper, who started things off with a well-rehearsed temper tantrum that segued into a strange, wonderfully choreographed number in which dancers dressed as spiders moved across the stage while Cooper's band played. It was big-time show business at its creative best. The aristocracy of the recording industry were being entertained, having come to honor the year's top performers, the creme de la creme, the ones who had sold the most records. Only in Technicolor dreams could you conceive of a Cinderella setting more unlikely than was set that night for a good ol' boy from Jacksonville, Florida. Wearing a smile as wide as a Southern drawl as he walked toward center stage, Leon Wilkeson, bass guitar player for the Lynyrd Skynyrd band, accepted the Golden Achievement award for what truly was a remarkable level of accomplishment for a bunch of musical misfits. It was a moment filled with irony.

Leon always enjoyed wearing odd hats, but for this gala affair he'd chosen an entire ensemble, and I'm sure that Hollywood's smart set wondered how he'd managed to get past the hotel doorman in the godawful get-up he wore. It was a tuxedo, but it wasn't the traditional James Bond look. The pants and jacket were the customary flat black, but cut with a western flair. The shirt was appropriately white but ruffled from neck to navel. And if that weren't enough of a fashion faux pas in this discerning crowd of sophisticates, all dressed to the nines, Leon added his own fanciful touch, a white cowboy hat and boots, and a wide leather belt with a pair of pearl-handled pistols in cream-colored holsters. These were unexpected accessories for a musician from a band that didn't perform Western tunes, especially when one of their top hits, "Saturday Night Special," is still the most strongly worded anti-handgun pop song ever written.

But regardless of how anyone may have felt about Leon's attire that evening, it was decidedly more fitting than his usual garb; besides, show business people can wear whatever they want, and he was just having fun. In fact, after the show he danced with Mae West. Leon's outfit simply affirmed the Southern maxim: you can take the boy out of the country, but you can't take the country out of the boy. That's a nice way to say what is often expressed in a single word, a word someone uttered quietly in the back of the auditorium when Leon rose to claim the award.

"Redneck."

For anyone who doesn't understand what a redneck is, I should explain. The term originated before the turn of the last century, when most Americans worked on farms and got sunburned necks from being outdoors all day. City dwellers tended to look down on uncultured country folks, and the label was custom-made. If you call a man a redneck today, you're also calling him ignorant, but that "ain't no big thing" if you're a redneck, too. In that case, you're both just good ol' boys wherever you live in this country, although a Southern drawl will usually leave no doubt. Jacksonville, Florida, was where the original Lynyrd Skynyrd band members grew up, and most of its residents' forebears had moved there from the rural areas of Northeast Florida and Southeast Georgia. And for Jacksonville, you didn't get any more country than the Westside.

Despite the magic of the moment when he stood on that stage in Hollywood, Leon was still just a redneck from the Westside of Jacksonville, Florida, and he never pretended to be otherwise. I'm the same way, and so was my best friend, Ronnie Van Zant, the founding father, chief songwriter and singer, and undisputed leader of Lynyrd Skynyrd. Ronnie had asked Leon to accept the award that night at the Beverly Hills Hotel because Ronnie avoided the limelight when he wasn't on stage, and besides, getting dressed up wasn't his style, not even for a prestigious award. For Ronnie, it was jeans and a T-shirt and maybe a hat, unless it was cold, and that's all it would ever be.

To understand Lynyrd Skynyrd, you have to understand Ronnie Van Zant, who, at the peak of his success, was still the same person he was when he started out. Except for his extraordinary talent and the musical skills of the boys in the band, all of us and the people we grew up with were average rednecks. Like the rest of the folks who lived in our part of town, it was manual labor that put bread on the table, just as it had for every other generation before us. Ronnie's father, Lacy Van Zant, made his living hauling goods up and down the East Coast in a big rig truck, and his mother, Marion Virginia "Sister" Hicks Van Zant, worked nights in a donut shop. Her grandfather had called her "Sister" as a child, and the nickname stuck. Lacy and Sister met near the end of the Second World War when he was home on leave from the U.S. Navy and she was just fifteen. They started dating when he left the service two years later, and one of their favorite outings was sitting in a car listening to the radio and singing along with the music. After a year-long courtship, Lacy and Marion began a marriage that would last fifty-three years, and together they would raise six children: the oldest was Jo Anne, Lacy's daughter from a previous marriage, followed by Ronnie, Donnie, Marlene, Darlene, and Johnny.

Lacy was always a good provider, but Sister was the glue that held the family together, especially with Lacy out on the road so much as a truck driver. Sister was a friendly person, generous with everyone she met, but she had a firm side, too, and she was never shy about standing up for what she felt was right, especially if it involved her family. Their house was always open to everybody in the neighborhood, and anyone who ever visited the Van Zants never failed to notice the genuine respect the children had for their parents, and the politeness their kids always showed for each other and for other people.

Lacy and Sister made their home a happy place for their children to grow up in. It was a close, loving family in which the kids were encouraged to enjoy life, to be happy about themselves as individuals, to be proud of who they were in spite of their humble station in life, and to live the American dream without being afraid to fail. It was in this nurturing environment that Ronnie developed his one great dream and all of the confidence he would ever need. The boy loved both of his parents, and as the oldest son of a man who let him be himself, he revered his father. Lacy stressed the value of education, and Ronnie tried hard to be a good student, serving on the school safety patrol in the sixth grade, and sometimes making the honor roll in his upper grades. But just a few credits short of finishing, he withdrew from school toward the end of his senior year.

Leaving high school was a decision Ronnie always regretted, and later in life he confessed that, despite his success, he felt he had failed to live up to his father's expectations. This wasn't true, of course, because Lacy's love for his son was boundless, and yet this feeling followed Ronnie for the rest of his life. It drove him to succeed, and even after he'd done that, it drove him to excel. Many years later, Ronnie told a reporter, "All I can preach is school. That's where power lies, . . . If I can come out of [Shantytown], you can do it. I made a bad mistake. You gotta have education." He'd put platinum record albums on his father's wall, "but never a diploma," he said.

Ronald Wayne Van Zant was born January 15, 1948, in Jacksonville, Florida, and he lived near the outskirts of town on the city's Westside. The Van Zants' home was at the corner of Mull Street and Woodcrest Road. I lived on Mull Street just a few houses away, in a rough, blue-collar area that Ronnie called "Shantytown." He'd heard it called that by the mother of one of his friends, Jim Daniel, who lived in a different neighborhood. Ronnie found it amusing at the time, but the truth was clear to see. The houses were simple structures built mostly of concrete block or wood. Some had missing windows and doors, and some had no electricity. Most streets were paved, but there were dirt roads, too, and one of them distinguished our neighborhood in a way that only a redneck could appreciate. Not really a road, it was a racetrack; and if there is one sport that rednecks enjoy more than all the rest it's stock car racing. Every Saturday night and on many a Sunday afternoon this oval-shaped circle of sand became redneck heaven, and in our neighborhood, if you weren't at the races you felt them anyway, their thunderous roar so loud it rattled windows and smothered conversation in every house. Just three blocks from where Ronnie and I lived, at the corner of Ellis Road and Plymouth Street, Jacksonville's Speedway Park was a metaphor for where our lives would lead: most of us would ride in a circle going nowhere while one of us rode to glory.

For the biggest races at Speedway Park, more than six thousand people would pack the place to capacity, filling the wooden grandstands, the pits, and the infield. Everyone who sat in the bleachers knew they'd be showered with dirt when the cars went past, even in the top rows. But the dirt hardly ever reached Ronnie, our friends, and me, because whatever the admission price was, we couldn't afford it. We watched the races from just outside the fence, perched in the tops of the trees that circled the track. Some races we didn't watch, but we often went there anyway, hoping for a chance to make a little money. Every once in a while a tire would come flying over the fence, and whoever grabbed it first would try to hide it, scheming to sell it later to one of the race car owners, but not to the one who'd lost it.

Few people know it, but Ronnie wasn't the first major recording artist from Jacksonville to watch the races from outside the fence at Speedway Park. Charles Eugene "Pat" Boone, whose parents had hoped to name their first child "Patricia," was born in Jacksonville in 1934 and went on to sell more records during the 1960s than everyone but Elvis Presley. A descendant of Daniel Boone, he appeared in a number of hit movies, including State Fair and Journey to the Center of the Earth; he had fifteen hits in the Top 10, including "April Love" and "Love Letters in the Sand," which stayed on the charts for thirty-four weeks; and he still holds Billboard magazine's all-time record of two hundred consecutive weeks on the charts with more than one song. Pat Boone was two years old when his family moved from his mother's hometown to Nashville, Tennessee, but on numerous occasions over a period of many years, while visiting relatives in Florida the Boones enjoyed going to Speedway Park. Although they could have purchased tickets (Boone's father was an architect/builder; his mother was a registered nurse), like so many others they preferred viewing the action close-up where they could feel the ground shake as the cars roared past, so they sat in custom-made "bleachers" set up in the beds of pickup trucks at the start of the back straightaway.

Speedway Park was the fastest half-mile dirt track in the nation because it was a "big half-mile." Measured on the inside, it was five-eighths of a mile around, which meant that drivers could reach higher speeds than they could manage on a standard half-mile course. Drawing thousands of fans from all over northeast Florida and southeast Georgia, Speedway Park was part of the National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing's (NASCAR) Grand National circuit, which later became the Winston Cup series. All of the famous drivers raced there. Richard Petty, Tiny Lund, Junior Johnson, Fireball Roberts, Bobby and Donnie Allison, David Ezell, Cale Yarborough, Lee Roy Yarbrough, and Wendell Scott.

One of the nation's top drivers, Lee Roy Yarbrough had his best year in 1969 by winning the Daytona 500 and two other major events. Yarbrough lived in our neighborhood, one block from the track, and starting in the early '60s Ronnie and I used to hang around while he worked on his car in the yard beside his house. We were probably ten years younger than Lee Roy, but he seemed to enjoy our company. Lee Roy was a real-life local sports hero for us, and as Ronnie got older and he began to think about his future, he used to say that he was going to be the most famous person to come out of Jacksonville since Lee Roy Yarbrough.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Van Zant dominates the book, and the authors effectively show both his hard-drinking, brawling side, and his softer touches.” —Publishers Weekly

“An admiring biography . . . disturbing and electrifying.” —Kirkus Reviews

“An admiring biography . . . disturbing and electrifying.” —Kirkus Reviews