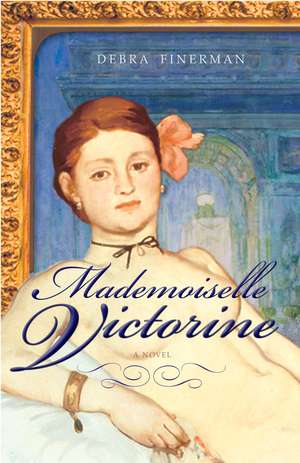

Mademoiselle Victorine: Mediterranean Flavors to Crave with Wines to Match

Autor Debra Finermanen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 iun 2007

When she becomes the favorite of the Duke de Lyon, the power behind the shaky government of Emperor Louis-Napoléon, her continued attraction to Manet becomes dangerous for them both. And when an astonishing secret from Victorine’s past comes to light, her carefully constructed world may come crashing down around her.

Mademoiselle Victorine transports readers back to nineteenth-century Paris, a time when art, love, and commerce blended seamlessly together.

Preț: 113.63 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 170

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.75€ • 23.63$ • 18.28£

21.75€ • 23.63$ • 18.28£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 31 martie-14 aprilie

Livrare express 14-20 martie pentru 62.35 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307352835

ISBN-10: 0307352838

Pagini: 293

Dimensiuni: 134 x 201 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.39 kg

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

ISBN-10: 0307352838

Pagini: 293

Dimensiuni: 134 x 201 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.39 kg

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

Recenzii

Mademoiselle Victorine plunges the reader into the volatile mix of art and political intrigue in 1860s Paris through the fascinating person of Victorine Laurent, whose rapid, determined rise from dancer to courtesan of kings exposes the lives and passions of her time. Mademoiselle Victorine rides the Parisian whirlwind, taking the reader so deep into the heart of that glittering and dangerous era that putting the book down will not be an option.

- Pamela Aidan, author of An Assembly Such As This

“As vivid, bold, and seductive as a Manet painting…brings to life the tinseled, tawdry art world of Second Empire Paris.

- Eleanor Herman, author of Sex with Kings: 500 Years of Adultery, Power, Rivalry, and Revenge

“Finerman cleverly weaves her touching story, populated with colorful, artistic characters, through a period in the political and artistic history of France that is rich with drama.”

¯Susanne Dunlap, author of Emilie’s Voice and Liszt’s Kiss

- Pamela Aidan, author of An Assembly Such As This

“As vivid, bold, and seductive as a Manet painting…brings to life the tinseled, tawdry art world of Second Empire Paris.

- Eleanor Herman, author of Sex with Kings: 500 Years of Adultery, Power, Rivalry, and Revenge

“Finerman cleverly weaves her touching story, populated with colorful, artistic characters, through a period in the political and artistic history of France that is rich with drama.”

¯Susanne Dunlap, author of Emilie’s Voice and Liszt’s Kiss

Extras

Chapter One

We always seek out forbidden things and long for whatever is denied us.

--Francois Rabelais, Gargantua and Pantagruel, 1532-1564

Outside the tall bow windows of the Paris Opera ballet school, dusk embraced the city in a grayish pink veil, settling around spires of cathedrals and draping across bridges of the Seine. Inside the cavernous rehearsal hall, Victorine Laurent's fellow students practiced plies under the critical eye of their pudgy dance master, Monsieur Jules. The violinist yawned as he scratched out a listless Chopin nocturne. The girls' middle-aged mothers nested on folding chairs, gossiping and clutching tattered shawls against the evening chill.

In the bright vestibule, Victorine cupped her hands against the glass-paned French doors and scanned the room for Edgar Degas. Was she too late for their appointment? No, there he was in his sketching corner, but not alone. Another gentleman stood with him off to the side, observing the girls in the flickering gaslight. When Degas caught sight of her, he nudged his companion and nodded his chin toward her. Victorine smoothed her dark curls. She tugged the decollete of her crimson taffeta frock just a touch lower, took a deep breath, and threw open the double doors, slicing the room with a shaft of light.

As she approached, Victorine's gaze riveted to the other gentleman. Degas introduced her, and Victorine lowered her face in the charming way she had practiced a thousand times in her cheval glass. Then she glanced up at the stranger, held his gaze a moment longer than was proper. The shine of a silk top hat, the sparkle of a gold watch chain, and the polish of leather boots spoke to her of affluence.

"So! This is the gentleman from Marseille you told me so much about." She smiled sweetly, extending her hand.

There was a moment of confusion before Degas realized the mistaken identity. "No, no, this isn't the banker chap. This is Edouard Manet! He's an artist, Victorine. He wants you to model for him."

She kept her smile, murmured it was a pleasure, then turned to walk away. Edouard Manet grabbed her wrist. "Wait a moment. What's wrong with artists? They can't afford to buy you a carriage and pair?"

So he understood where her priorities lay.

"I've never heard of you, Monsieur Manet. Have you exhibited in the Salon?"

"He has," Degas said. "Just not very often."

The yearly Salon competition sponsored by the prestigious Academie francaise held the entire city of Paris enthralled. It was ostensibly open to all artists, but everyone knew that the conservative jury was notable for rejecting work deemed too iconoclastic.

"I'd wager you've never seen paintings like mine." Edouard scribbled an address on the back of his calling card. "Come to the studio, judge my work, then decide." He watched her face closely. "I pay my models well."

A flicker of interest lit her eyes. "I'll consider it. But if I agree to model for you, I insist Monsieur Degas be present as chaperone."

"You flatter yourself, mademoiselle," Edouard laughed. "When I choose a model, it's for the music inside them."

She was taken aback by the poetry of his remark. "Do I possess music?" Her tone turned soft.

"Perhaps."

Victorine pulled her thin wool mantelet closer around her shoulders as she and Degas sipped cremes in the cool morning air. They chatted under the green canvas awning of her favorite cafe near the cathedral of Notre-Dame-de-Lorette, in the quartier where she and many young women of her social class lived. They were called lorettes--not quite as debased as streetwalkers, not quite as exalted as courtesans.

"After boarding school, Manet could have followed his father's wishes and become a barrister or chosen a position in banking or the stock exchange," Degas said. "But he has a talent that will propel him higher." Degas sat back. "He has the hands of an artist coupled with the passion of a revolutionary. With paintbrush and canvas he's going to change the way the world's perceived." Degas named obscure artists Victorine had never heard of--Monet, Renoir, and Cezanne--who had chosen Edouard Manet as their Apollo. "Of them all, Manet has the cool, analytical intelligence to be a painter of his own time."

Victorine swirled the spoon in her cup, contemplating Manet. "Tell him I'll come tomorrow afternoon at three."

The next day at the scheduled hour, Victorine knocked at the black lacquered door of Edouard Manet's flat. As footsteps approached inside, she glanced down and noticed that her hem was splattered with the reddish brown mud of Paris's ubiquitous construction pits. And it was her best dress, the only one made of silk satin. Her side-laced ankle boots were caked with mud as well. Too late now to regret walking to save six sous on omnibus fare.

The door swung open and Edouard bowed with an exaggerated flair.

Victorine paused under the shimmering gas jets of the foyer chandelier to untie the lilac satin ribbons of her cabriolet bonnet and placed it with her fringed parasol on the marble-top bureau. She knew that even within the modest budget of a lorette she looked as delectable as a candy box in a confectionery shop; her luxuriant dark hair, swept back into a sophisticated chignon, had taken her hairdresser painstaking time to accomplish. The faux pearl-and-rhinestone earrings pulled the eye to her expertly powdered and rouged face, pink and white as a Fragonard galante, perfect in every feature. Except. Except for a cruel oval scar below her left cheek, which marred the flawless surface. Sensing Edouard appreciatively scanning her from behind, she swayed a bit more seduction into her hips, a cascade of lilac satin ruffles sweeping the dusty floorboards with each step. As she approached the parlor, she glanced at the fine upholstered furnishings, the damask drapes tied back with tasseled silk cords, the gleaming mahogany end tables, and puzzled over the incongruity of these treasures residing in an obscure young artist's studio in the seedy Batignolles district.

In the parlor, she met Degas with a quick kiss to both cheeks while two other gentlemen rose from the crimson velvet divan. The older, distinguished-looking one was a Corinthian column of a man exuding a powerful presence and intimidating demeanor. The other, a willowy chap with vaguely feminine features, was shorter than Victorine and slight of build. What a comical picture they created standing side by side.

Edouard introduced the younger man as Andre, the Marquis de Montpellier. He adjusted his cravat and slicked back a stray lock of fine, blond hair. The soft peach fuzz on his cheeks and the spray of freckles across his nose hinted that he could be no more than her age, seventeen, or eighteen at the most. She commented that her favorite shopping street in Paris was the boulevard de Montpellier, no doubt named for his illustrious ancestors? He replied that he was just a humble writer, and could take no credit for his family's storied past. Judging by his threadbare suit of clothes, Victorine surmised that the family had moved out of the ancestral chateau and into the caretaker's cottage several generations ago.

The older gentleman waited patiently for his turn. Edouard introduced him as Monsieur Baudelaire. She instantly recognized the name of Charles Baudelaire, the poet and author, esteemed as one of the greatest thinkers of the age.

"Monsieur Baudelaire, this is an honor. I'm a great admirer of your work."

Not one to be as inveigled as the young marquis by flattery, Baudelaire questioned her as to which, if any, of his "humble scribblings" she had read?

She wanted him to know that she had a good education, wasn't some vulgar cocotte from the streets. "I loved an essay you published recently about women. I committed a phrase to memory: 'Woman is a divinity, a star which presides over all the conceptions of the brain of Man.'"

"Quite right, my essay in Le Figaro last week!" He seemed impressed. He asked how Victorine had come to meet Manet.

"I pressed Degas for an introduction after seeing her in one of his pastel sketches," Edouard said.

"I can't blame Manet for being intrigued by your beauty." Baudelaire smiled at Victorine.

"Not mere beauty," Edouard said. "Beneath the surface, there's light and shadow."

The four gentlemen fell silent and scrutinized her. Victorine felt like a display at Le Bon Marche department store.

"Such opposites warring in one human being, that's the entire matter right there, isn't it? Chiaroscuro," Edouard said.

Victorine asked the meaning of that foreign word.

"Light and shadow. It's Italian," Edouard explained.

"Victorine, you told me your parents were famous Italian musicians. Didn't you say they toured the Continent performing for royalty?" Degas asked.

"You must have me confused with someone else. I was born in Vienna. My father was fencing master at the Habsburg court."

By the looks exchanged between the gentlemen, she could see they didn't believe her. After all, it was common knowledge that girls in the corps de ballet hailed from poor working-class backgrounds. The junior ballerinas were amateurs chosen for their beauty, not their dancing skills, to perform in the short ballet entr'acte. They supplemented their meager salaries by becoming the coddled mistresses of rich married bankers, real estate speculators, and industrialists. No sophisticated person believed that a love of Wagner or Verdi brought these nouveaux riches to the Opera every Thursday; they came solely to admire their mistresses' long legs in short tutus. Gossip in the dressing room usually centered on ballerinas who had been passed around by wealthy protectors for years, only to resort to common street prostitution. But Victorine had no intention of following that downward spiral. She was seventeen and knew she had only a few good years left. She took Edouard's arm. "Where are these masterpieces of yours, Monsieur Manet? If I'm to sit for a portrait, I'd better see what I've gotten myself into."

Edouard led her to the hallway lined with canvases. There were landscapes, cityscapes, and portraits of women. Many women. One after another, she surveyed the paintings without comment, twisting her gloves in her hands as she evaluated the intense colors and the thick impasto slashed on the canvas by palette knife. Edouard followed one step behind.

"Well"--she turned to him at last--"thank you."

"Don't you like my work?" He seemed crushed.

"I don't want to say they're good or bad." She chose her words as thoughtfully as a woman trying on hats in a millinery shop. "I can only say I don't understand them. This one." She pointed to a group portrait of outdoor concertgoers in a shady garden setting. "Some faces in the crowd have features, while others are blurred. And this one." She indicated a portrait of an old peasant. "They say one judges an artist's talent by how he depicts the hands. Those hands look like lumps of raw dough. I don't wish to insult your art, but . . ." She turned back to his pictures with a shrug.

"Mademoiselle." Baudelaire stepped forward. "Consider for a moment. Why do you feel uncomfortable? Critics feel uneasy because it's too radical. But should a modern artist imitate the ancient world, model the human figure after a classical Greek sculpture? Do we stroll the streets of Paris in togas?"

"No . . . but an artist should paint subjects as he truly sees them."

"That's precisely what he does! When one looks, one sees refracted light, not colors. Light is a symbol of our time, and Manet is a master of that light."

"Baudelaire, please . . . ," Edouard protested.

Baudelaire held up his hand for silence. "Leonardo taught his students saper vedere--knowing how to see. Manet is the Leonardo of our times. Someday his talent will be recognized."

She glanced at the pictures lined up across the wall and calculated her options. They didn't know her yet, could little fathom that she was preoccupied with one thing: the search for a wealthier, more powerful replacement for Dr. LeBrun, the married dentist who currently paid her rent and dressmaker bills. She deliberated that being associated with Manet and his odd painting style might damage her reputation. Yet it was also possible that with a portrait on display at the Salon for all to see, her image would be exposed to a wide audience of potential suitors and she could rise faster up the ladder of success. She had read about a man named P. T. Barnum in America who used this phenomenon--"advertising"--to profitable effect. "Yes, I will sit for you, Monsieur Manet."

They drank some fine Veuve Clicquot, and Victorine felt Edouard's gaze luxuriate in the curves of her shoulders and slide down the nape of her neck. She caught his glance, evaluating her skin tone, cream of custard, and tracing her mouth, the aspect of angel's wings, and lingering over the scar. He reached out to touch it. "How did you--"

"Don't ask me about that." She jerked her head away. "Tomorrow morning, ten o'clock. We'll begin work."

He grasped her hand, but she recoiled.

"Don't expect anything more." Her voice had the sound of a door slamming shut. "You're not what I want."

"Not what you want?"

"Not what I need." Her voice softened.

"As you wish," he said. "A strictly professional relationship."

She allowed him to escort her to the hallway as the other men watched, and felt his gaze following her as she walked down the four flights of marble steps. She wanted him to understand from the start that there was to be no love affair, nothing to distract her from her goal: financial security. As Victorine stepped onto the boulevard des Batignolles, dusk was falling and the lamplighters with their long poles illuminated the streetlamps. How difficult would it be to keep Manet at a distance while engaging in the intimate act of posing for him? Judging from the numerous portraits of women in the studio and the tender way he touched her face, he was accustomed to females succumbing to the Manet charm. But she was accustomed to balding heads, middle-aged paunches, and the financial benefits an aged mouth on hers could provide.

Chapter Two

'Tis to create, and in creating live.

--Lord Byron, Childe Harold's Pilgrimage, 1812

Victorine knocked for several minutes and began to doubt that anyone was home. As she turned to leave, the door creaked open to reveal Andre de Montpellier cinching closed his silk dressing gown. He smoothed down a cowlick of fine, blond hair and welcomed her in, waving a brown bottle of elixir and mumbling about his delicate constitution and a devilish bout of dyspepsia.

"Do you live here?" Victorine asked, glancing at him as he weaved down the foyer behind her.

"My rent's in arrears and I'm staying with Manet until payday next week at Le Moniteur."

Victorine considered this new tidbit. "You work for a newspaper?" she asked.

"I'm writing a literary masterpiece, but I make ends meet with a weekly gossip piece you may have seen called 'La Vie Parisienne.'"

We always seek out forbidden things and long for whatever is denied us.

--Francois Rabelais, Gargantua and Pantagruel, 1532-1564

Outside the tall bow windows of the Paris Opera ballet school, dusk embraced the city in a grayish pink veil, settling around spires of cathedrals and draping across bridges of the Seine. Inside the cavernous rehearsal hall, Victorine Laurent's fellow students practiced plies under the critical eye of their pudgy dance master, Monsieur Jules. The violinist yawned as he scratched out a listless Chopin nocturne. The girls' middle-aged mothers nested on folding chairs, gossiping and clutching tattered shawls against the evening chill.

In the bright vestibule, Victorine cupped her hands against the glass-paned French doors and scanned the room for Edgar Degas. Was she too late for their appointment? No, there he was in his sketching corner, but not alone. Another gentleman stood with him off to the side, observing the girls in the flickering gaslight. When Degas caught sight of her, he nudged his companion and nodded his chin toward her. Victorine smoothed her dark curls. She tugged the decollete of her crimson taffeta frock just a touch lower, took a deep breath, and threw open the double doors, slicing the room with a shaft of light.

As she approached, Victorine's gaze riveted to the other gentleman. Degas introduced her, and Victorine lowered her face in the charming way she had practiced a thousand times in her cheval glass. Then she glanced up at the stranger, held his gaze a moment longer than was proper. The shine of a silk top hat, the sparkle of a gold watch chain, and the polish of leather boots spoke to her of affluence.

"So! This is the gentleman from Marseille you told me so much about." She smiled sweetly, extending her hand.

There was a moment of confusion before Degas realized the mistaken identity. "No, no, this isn't the banker chap. This is Edouard Manet! He's an artist, Victorine. He wants you to model for him."

She kept her smile, murmured it was a pleasure, then turned to walk away. Edouard Manet grabbed her wrist. "Wait a moment. What's wrong with artists? They can't afford to buy you a carriage and pair?"

So he understood where her priorities lay.

"I've never heard of you, Monsieur Manet. Have you exhibited in the Salon?"

"He has," Degas said. "Just not very often."

The yearly Salon competition sponsored by the prestigious Academie francaise held the entire city of Paris enthralled. It was ostensibly open to all artists, but everyone knew that the conservative jury was notable for rejecting work deemed too iconoclastic.

"I'd wager you've never seen paintings like mine." Edouard scribbled an address on the back of his calling card. "Come to the studio, judge my work, then decide." He watched her face closely. "I pay my models well."

A flicker of interest lit her eyes. "I'll consider it. But if I agree to model for you, I insist Monsieur Degas be present as chaperone."

"You flatter yourself, mademoiselle," Edouard laughed. "When I choose a model, it's for the music inside them."

She was taken aback by the poetry of his remark. "Do I possess music?" Her tone turned soft.

"Perhaps."

Victorine pulled her thin wool mantelet closer around her shoulders as she and Degas sipped cremes in the cool morning air. They chatted under the green canvas awning of her favorite cafe near the cathedral of Notre-Dame-de-Lorette, in the quartier where she and many young women of her social class lived. They were called lorettes--not quite as debased as streetwalkers, not quite as exalted as courtesans.

"After boarding school, Manet could have followed his father's wishes and become a barrister or chosen a position in banking or the stock exchange," Degas said. "But he has a talent that will propel him higher." Degas sat back. "He has the hands of an artist coupled with the passion of a revolutionary. With paintbrush and canvas he's going to change the way the world's perceived." Degas named obscure artists Victorine had never heard of--Monet, Renoir, and Cezanne--who had chosen Edouard Manet as their Apollo. "Of them all, Manet has the cool, analytical intelligence to be a painter of his own time."

Victorine swirled the spoon in her cup, contemplating Manet. "Tell him I'll come tomorrow afternoon at three."

The next day at the scheduled hour, Victorine knocked at the black lacquered door of Edouard Manet's flat. As footsteps approached inside, she glanced down and noticed that her hem was splattered with the reddish brown mud of Paris's ubiquitous construction pits. And it was her best dress, the only one made of silk satin. Her side-laced ankle boots were caked with mud as well. Too late now to regret walking to save six sous on omnibus fare.

The door swung open and Edouard bowed with an exaggerated flair.

Victorine paused under the shimmering gas jets of the foyer chandelier to untie the lilac satin ribbons of her cabriolet bonnet and placed it with her fringed parasol on the marble-top bureau. She knew that even within the modest budget of a lorette she looked as delectable as a candy box in a confectionery shop; her luxuriant dark hair, swept back into a sophisticated chignon, had taken her hairdresser painstaking time to accomplish. The faux pearl-and-rhinestone earrings pulled the eye to her expertly powdered and rouged face, pink and white as a Fragonard galante, perfect in every feature. Except. Except for a cruel oval scar below her left cheek, which marred the flawless surface. Sensing Edouard appreciatively scanning her from behind, she swayed a bit more seduction into her hips, a cascade of lilac satin ruffles sweeping the dusty floorboards with each step. As she approached the parlor, she glanced at the fine upholstered furnishings, the damask drapes tied back with tasseled silk cords, the gleaming mahogany end tables, and puzzled over the incongruity of these treasures residing in an obscure young artist's studio in the seedy Batignolles district.

In the parlor, she met Degas with a quick kiss to both cheeks while two other gentlemen rose from the crimson velvet divan. The older, distinguished-looking one was a Corinthian column of a man exuding a powerful presence and intimidating demeanor. The other, a willowy chap with vaguely feminine features, was shorter than Victorine and slight of build. What a comical picture they created standing side by side.

Edouard introduced the younger man as Andre, the Marquis de Montpellier. He adjusted his cravat and slicked back a stray lock of fine, blond hair. The soft peach fuzz on his cheeks and the spray of freckles across his nose hinted that he could be no more than her age, seventeen, or eighteen at the most. She commented that her favorite shopping street in Paris was the boulevard de Montpellier, no doubt named for his illustrious ancestors? He replied that he was just a humble writer, and could take no credit for his family's storied past. Judging by his threadbare suit of clothes, Victorine surmised that the family had moved out of the ancestral chateau and into the caretaker's cottage several generations ago.

The older gentleman waited patiently for his turn. Edouard introduced him as Monsieur Baudelaire. She instantly recognized the name of Charles Baudelaire, the poet and author, esteemed as one of the greatest thinkers of the age.

"Monsieur Baudelaire, this is an honor. I'm a great admirer of your work."

Not one to be as inveigled as the young marquis by flattery, Baudelaire questioned her as to which, if any, of his "humble scribblings" she had read?

She wanted him to know that she had a good education, wasn't some vulgar cocotte from the streets. "I loved an essay you published recently about women. I committed a phrase to memory: 'Woman is a divinity, a star which presides over all the conceptions of the brain of Man.'"

"Quite right, my essay in Le Figaro last week!" He seemed impressed. He asked how Victorine had come to meet Manet.

"I pressed Degas for an introduction after seeing her in one of his pastel sketches," Edouard said.

"I can't blame Manet for being intrigued by your beauty." Baudelaire smiled at Victorine.

"Not mere beauty," Edouard said. "Beneath the surface, there's light and shadow."

The four gentlemen fell silent and scrutinized her. Victorine felt like a display at Le Bon Marche department store.

"Such opposites warring in one human being, that's the entire matter right there, isn't it? Chiaroscuro," Edouard said.

Victorine asked the meaning of that foreign word.

"Light and shadow. It's Italian," Edouard explained.

"Victorine, you told me your parents were famous Italian musicians. Didn't you say they toured the Continent performing for royalty?" Degas asked.

"You must have me confused with someone else. I was born in Vienna. My father was fencing master at the Habsburg court."

By the looks exchanged between the gentlemen, she could see they didn't believe her. After all, it was common knowledge that girls in the corps de ballet hailed from poor working-class backgrounds. The junior ballerinas were amateurs chosen for their beauty, not their dancing skills, to perform in the short ballet entr'acte. They supplemented their meager salaries by becoming the coddled mistresses of rich married bankers, real estate speculators, and industrialists. No sophisticated person believed that a love of Wagner or Verdi brought these nouveaux riches to the Opera every Thursday; they came solely to admire their mistresses' long legs in short tutus. Gossip in the dressing room usually centered on ballerinas who had been passed around by wealthy protectors for years, only to resort to common street prostitution. But Victorine had no intention of following that downward spiral. She was seventeen and knew she had only a few good years left. She took Edouard's arm. "Where are these masterpieces of yours, Monsieur Manet? If I'm to sit for a portrait, I'd better see what I've gotten myself into."

Edouard led her to the hallway lined with canvases. There were landscapes, cityscapes, and portraits of women. Many women. One after another, she surveyed the paintings without comment, twisting her gloves in her hands as she evaluated the intense colors and the thick impasto slashed on the canvas by palette knife. Edouard followed one step behind.

"Well"--she turned to him at last--"thank you."

"Don't you like my work?" He seemed crushed.

"I don't want to say they're good or bad." She chose her words as thoughtfully as a woman trying on hats in a millinery shop. "I can only say I don't understand them. This one." She pointed to a group portrait of outdoor concertgoers in a shady garden setting. "Some faces in the crowd have features, while others are blurred. And this one." She indicated a portrait of an old peasant. "They say one judges an artist's talent by how he depicts the hands. Those hands look like lumps of raw dough. I don't wish to insult your art, but . . ." She turned back to his pictures with a shrug.

"Mademoiselle." Baudelaire stepped forward. "Consider for a moment. Why do you feel uncomfortable? Critics feel uneasy because it's too radical. But should a modern artist imitate the ancient world, model the human figure after a classical Greek sculpture? Do we stroll the streets of Paris in togas?"

"No . . . but an artist should paint subjects as he truly sees them."

"That's precisely what he does! When one looks, one sees refracted light, not colors. Light is a symbol of our time, and Manet is a master of that light."

"Baudelaire, please . . . ," Edouard protested.

Baudelaire held up his hand for silence. "Leonardo taught his students saper vedere--knowing how to see. Manet is the Leonardo of our times. Someday his talent will be recognized."

She glanced at the pictures lined up across the wall and calculated her options. They didn't know her yet, could little fathom that she was preoccupied with one thing: the search for a wealthier, more powerful replacement for Dr. LeBrun, the married dentist who currently paid her rent and dressmaker bills. She deliberated that being associated with Manet and his odd painting style might damage her reputation. Yet it was also possible that with a portrait on display at the Salon for all to see, her image would be exposed to a wide audience of potential suitors and she could rise faster up the ladder of success. She had read about a man named P. T. Barnum in America who used this phenomenon--"advertising"--to profitable effect. "Yes, I will sit for you, Monsieur Manet."

They drank some fine Veuve Clicquot, and Victorine felt Edouard's gaze luxuriate in the curves of her shoulders and slide down the nape of her neck. She caught his glance, evaluating her skin tone, cream of custard, and tracing her mouth, the aspect of angel's wings, and lingering over the scar. He reached out to touch it. "How did you--"

"Don't ask me about that." She jerked her head away. "Tomorrow morning, ten o'clock. We'll begin work."

He grasped her hand, but she recoiled.

"Don't expect anything more." Her voice had the sound of a door slamming shut. "You're not what I want."

"Not what you want?"

"Not what I need." Her voice softened.

"As you wish," he said. "A strictly professional relationship."

She allowed him to escort her to the hallway as the other men watched, and felt his gaze following her as she walked down the four flights of marble steps. She wanted him to understand from the start that there was to be no love affair, nothing to distract her from her goal: financial security. As Victorine stepped onto the boulevard des Batignolles, dusk was falling and the lamplighters with their long poles illuminated the streetlamps. How difficult would it be to keep Manet at a distance while engaging in the intimate act of posing for him? Judging from the numerous portraits of women in the studio and the tender way he touched her face, he was accustomed to females succumbing to the Manet charm. But she was accustomed to balding heads, middle-aged paunches, and the financial benefits an aged mouth on hers could provide.

Chapter Two

'Tis to create, and in creating live.

--Lord Byron, Childe Harold's Pilgrimage, 1812

Victorine knocked for several minutes and began to doubt that anyone was home. As she turned to leave, the door creaked open to reveal Andre de Montpellier cinching closed his silk dressing gown. He smoothed down a cowlick of fine, blond hair and welcomed her in, waving a brown bottle of elixir and mumbling about his delicate constitution and a devilish bout of dyspepsia.

"Do you live here?" Victorine asked, glancing at him as he weaved down the foyer behind her.

"My rent's in arrears and I'm staying with Manet until payday next week at Le Moniteur."

Victorine considered this new tidbit. "You work for a newspaper?" she asked.

"I'm writing a literary masterpiece, but I make ends meet with a weekly gossip piece you may have seen called 'La Vie Parisienne.'"

Descriere

Inspired by real women, this historical page-turner transports readers to 1860s Paris--to the cafs, art studios, and elegant parties of high society--just as the old world and the new began to collide.

Notă biografică

Debra Finerman