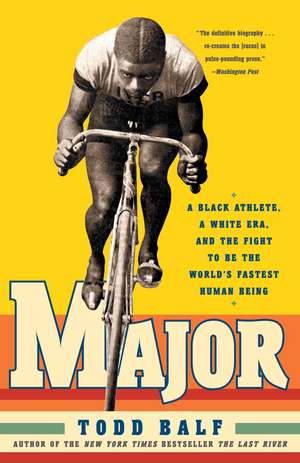

Major: A Black Athlete, a White Era, and the Fight to Be the World's Fastest Human Being

Autor Todd Balfen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 dec 2008 – vârsta de la 14 până la 18 ani

At the turn of the 20th century, hundreds of lightning-fast racers won the hearts and minds of a bicycling-crazed public. Scientists studied them, newspapers glorified them, and millions of dollars in purse money were awarded to them. Major Taylor aimed to be the fastest of them all.

Taylor’s most formidable and ruthless opponent-a man nicknamed the "Human Engine" was Floyd McFarland. One man was white, one black; one from a storied Virginia family, the other descended from Kentucky slaves; one celebrated as a hero, one trying to secure his spot in a sport he dominated. The only thing they had in common was the desire to be named the fastest man alive. Finally, in 1904, both men headed to Australia for a much-anticipated title match to decide who would claim the coveted title.

Major is the story of a superstar nobody saw coming, the account of a fierce rivalry that would become an archetypal tale of white versus black in the 20th century, and, most of all, the tale of our nation’s first black sports celebrity.

Preț: 111.51 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 167

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.34€ • 23.19$ • 17.90£

21.34€ • 23.19$ • 17.90£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 04-18 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307236593

ISBN-10: 0307236595

Pagini: 306

Ilustrații: B&W PHOTOGRAPHS

Dimensiuni: 135 x 204 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

ISBN-10: 0307236595

Pagini: 306

Ilustrații: B&W PHOTOGRAPHS

Dimensiuni: 135 x 204 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

Recenzii

"Balf revels in the bicycle’s bone-shaking evolution and the top-gun fraternity of daredevils who literally risked life and limb to race."

—Entertainment Weekly

"With Major, Todd Balf has given us an astonishing book about race and racing in Gilded Age America. This is literary sports writing at its finest. In the tradition of David Halberstam and Frank DeFord, Balf painst intimate portraits of young athletes at the top of their game- and takes us on an epic ride to a nearly forgotten world of sport."

–Hampton Sides, author of Blood and Thunder and Ghost Soldiers

"If a literary magician could somehow combine the longshot thrill of Seabiscuit, the groundbreaking nobility of Jackie Robinson, and the dramatic flair of Babe Ruth, the result would be something close to this book. Major Taylor is perhaps the greatest American underdog story ever told; I couldn't put it down."

-- Daniel Coyle, author of Lance Armstrong's War and Hardball

"In Major, Todd Balf has given us the true story of a fascinating, vanished sports world, and one of America's first, great black champions. It reads as fast and as beautifully as its heroes spin."

-- Kevin Baker, author of Paradise Alley and Dreamland

From the Hardcover edition.

—Entertainment Weekly

"With Major, Todd Balf has given us an astonishing book about race and racing in Gilded Age America. This is literary sports writing at its finest. In the tradition of David Halberstam and Frank DeFord, Balf painst intimate portraits of young athletes at the top of their game- and takes us on an epic ride to a nearly forgotten world of sport."

–Hampton Sides, author of Blood and Thunder and Ghost Soldiers

"If a literary magician could somehow combine the longshot thrill of Seabiscuit, the groundbreaking nobility of Jackie Robinson, and the dramatic flair of Babe Ruth, the result would be something close to this book. Major Taylor is perhaps the greatest American underdog story ever told; I couldn't put it down."

-- Daniel Coyle, author of Lance Armstrong's War and Hardball

"In Major, Todd Balf has given us the true story of a fascinating, vanished sports world, and one of America's first, great black champions. It reads as fast and as beautifully as its heroes spin."

-- Kevin Baker, author of Paradise Alley and Dreamland

From the Hardcover edition.

Notă biografică

TODD BALF is the author of the New York Times bestseller The Last River and The Darkest Jungle. He is a former senior editor for Outside magazine.

Extras

Chapter 1

Free

July 1865

CITY OF LONDON

Atlantic Ocean

It glides along as though it were alive, and with

a smooth grace . . . everlasting and beautiful to behold.

--Scientific American

Magazine on the early pedal-powered bicycle

The South was still burning. Thousands of Confederate POWs remained in Union custody, having refused allegiance to their Yankee victors, and only a partial accounting of the 623,000 war dead had been made. It was a mere eight weeks after Appomattox and the end of the Civil War, but people were already on the move. The promise of America's large northern industrial cities, where work could be had and lives remade, triggered a massive response home and abroad.

The swell of humanity included a twenty-two-year-old French mechanic whose July transatlantic passage was notable because of what he steadfastly towed in a large clanging steamer trunk. Within were the unassembled parts of the first modern-era bicycle to land upon U.S. shores. Pierre Lallement, a baby-faced man with short legs and a penguin's stride, was the first of what would be a very long line of dreamers, schemers, and spectacular failures who would see in the beautiful symmetry of moving bicycle parts a new beginning. His wrought-iron frame didn't look like much, but he won a patent in 1866 and, more incredible still, he rode the thing, nobly taking to the green at New Haven, Connecticut, as a few rubbernecking strollers looked on.

Lallement's bicycle was, in truth, a giant advance that somehow eluded the best and brightest minds for generations, with "two wooden wheels, with iron tires, of nearly equal size, one before the other, surmounted by a wooden perch." The patent description, however, failed to emphasize the genius of the new design--foot pedals that would not just propel it but balance it. For the first time a rider could elevate his feet from terra firma (earlier versions were straddled and powered by hard, scooter-style pushes), drive his wherewithal into foot pedal cranks, and directly propel his earthly volume. One hundred and fifty years later it is the advance that a six-year-old who rides a bicycle for the first time remembers, the moment when the ground gives way, the wind sweetens, and nerve ends spark like dry tinder. It is the moment when doubt and fear release in a simple, fundamental expression of pungent emotion--something that sounds like "Wheeeee!"

Lallement didn't wait around long enough to see his bicycle gain acceptance--after a few years of queer looks and uneventful sales he glumly sailed back to France--but Americans did briefly experience a faddish burst of enthusiasm. It only lasted a year or two before they sharply turned on the contraption, dubbing the hard mechanical horse the "boneshaker." It was uncomfortable, unreliable, and rather awkward (the pedals were attached to the front wheel and not directly beneath the rider). Showcase races at outdoor courses did nothing to help the cause, as even supremely fit men on state-of-the art velocipedes (the precious-sounding term for the premodern steed) found walking speeds hard to best. It was not a racing bicycle. In a post-Civil War world where urban Americans had lofty expectations of a European-style enlightenment, the bike didn't measure up. By 1870, only five years after Lallement's dodgy transatlantic adventure, the primitive boneshaker was far more dead than alive.

Still, the sense among believers that they were in the proverbial ballpark and that the bicycle might be more than a fling stubbornly prevailed--especially in Europe, where English inventors one-upped their Parisian counterparts with the high-wheeler, the aptly described evolutionary follow-up to the boneshaker. With a lightweight hollow steel frame and cushioning seat spring, the British-made Ordinary was a far better vehicle than the boneshaker--her smooth, fast ride softened the old criticism--but the improvements came at the expense of what appeared to be life and limb. When the first ones were shipped to the United States in the late 1870s (unlike Europeans, it took a while for Americans to shake off the painful memory of its forebear) the new bicycle both enthralled and terrified Victorian America. Of his own experiences the early bicycling advocate Charles E. Pratt wrote, "It runs, it leaps, it rears and writhes; it is in infinite restless motion, like a bundle of sensitive nerves; it is beneath its rider like a thing of life."

The rider was a stratospheric eight feet off the ground, making a first encounter distressingly akin to sitting atop a moving lamppost. Children were particularly endangered. When Major Taylor was first starting to race, the old-timers initiated him by placing him atop the towering Ordinary, then sat back to watch and wait for the expected fall. The pedals were attached to the front wheel, the way they are on a tricycle. Unlike a tricycle, a Sisyphean thrust was required to budge the four-foot-diameter, hard-tired wheel. Brakes were primitive (or nonexistent), and a gentlemanly upright posture made the slightest puff of wind a worthy opponent. Literally and figuratively, a leap of faith was necessary to balance on tiny pedals and grossly dissimilar-sized wheels. The high-wheeler virtually ensured that a stalwart, risk-averse citizen who adored certainty, and for whom dignity was zealously sought in every waking moment, would be monstrously disappointed.

A technical explanation didn't alleviate the concern. Wheels, one small, the other enormous, were aligned so that the oversized rim supported the rider's center of gravity. Once in motion, scientists observed, "the physical forces generated by the rotation of the wheels produced a self steering effect." The technical term was precession. Perversely, the stabilizing force that kept one upright increased the faster you went. In other words, you had to risk life in the hope of saving it. The high-wheel bicycle, the popular frame design in America prior to 1890, didn't defy physical law, but it did challenge it.

Despite these immense challenges, a 19th-century person's motivation to learn to ride, once sufficiently teased by seeing others in motion, was unparalleled. Buttoned-up, pickled Victorians had too long stifled the pulsing in their chests. They desperately needed an emotional outlet; they wanted to flush their cheeks with color, expand their lungs with air, and swiftly glide from town to town. As a Nickell writer explained, every man was born with some of the "trick instinct." He meant that there was something innate and unseen, like luxurious black oil beneath the earth's still granite mantle, that lay untapped in everyone. Soon America seemed hell-bent on probing the great unknown. Thus, there were a multitude of horrible accidents, but also the kind of magnificence and magic the boneshaker never afforded. Wrote H. G. Wells in his fictional narrative of a neophyte's experience in the English countryside, "[Hoopdriver] wheeled his machine up Putney Hill, and his heart sang within him." Indeed, hearts sang and bicycles led the lovelorn to the bucolic, the exotic, and reputation-making hero climbs such as Ford Hill in Philadelphia. Those who were previously sedentary and waiting tremulously for the inevitable ravages of illness to overtake them flew into delighted, freewheeling motion. Lightness shone through the bleak day-to-day. Underdogs rejoiced.

Unlike in the boneshaker era, being a spectator was nearly as fun. In the summer of 1878, the same year both Taylor and McFarland were born, a former shoe manufacturer named Albert Pope launched his Columbia brand--the first American-manufactured high-mount-- by sponsoring the country's first race on American-made bicycles. It was a precocious moment, bicycles being the hoped-for leader of a burgeoning postwar renaissance in physical sports. There was excited talk of the newly addictive "Athletic Impulse," of the way sports glorified our culture and ennobled the men who gamely partook. A keenness for outdoor sports had emerged, one that made the rising generation "big and lusty and pleasant to look at." Soon records were being broken: all kinds, all places. Neither foot racers nor most fleet Thoroughbreds could compare. In a span of only a few years the mile record, the benchmark for true, life-changing speed, was reduced from six minutes to less than three.

Pope's Boston Back Bay velodrome, site of that first American-style bicycle extravaganza, consisted of a planked cycling track inside a mammoth 320-foot-long tent. For several weeks high-wheel racers from Boston and imports from England and France hazarded gale-force winds and bitter Thanksgiving cold, racing distances up to 100 miles on the ten-laps-to-the-mile track. The French champion Charles Terront, an incorrigible ladies' man, wore snug white flannel knee breeches, blue stockings, and a silk ascot. His English rival quoted Shakespeare and went by the racing nom de guerre "Happy Jack." There was an American entry--an ancestral link to Major Taylor, Floyd McFarland, and even Lance Armstrong. Unfortunately, he wasn't deemed important enough to be mentioned by name in the press. Each day they rode with brave, unchecked abandon, their bicycles weighing a thumping thirty pounds.

Fans warmed to the activity in a way that inspired Pope and his rival manufacturers. They saw the potential of the market and began to ramp up. When the American neophyte hit a pole at a top-end speed of 20 mph, an amused London visitor described the bone-snapping collision as "an aerial flight to Mother Earth via the over-the-handles route."

Cycling as an American spectator sport had the necessary toehold.

Louis de Franklin Munger, a young hawk-nosed Detroit lad working in a blind-making factory, was one of the thousands of adventure-seeking American men swept into the craze. He had thick, pugnacious features but soft green eyes and almost aboriginal high cheekbones. Heretofore, the factories were the spectacle of his generation. The massive brick establishments, running along America's wide riverbanks, were symbols of progress and power and modernization. The shoppy smell of coal and coke choked the air; the homes nearby were blackened with a sooty film. On the factory floor the cacophony of surfacing machines, water pumps, air compressors, hammers, and pneumatic tools made it impossible to hear--the vibration saturated the body and didn't ever fully dissipate, not even in sleep. Young men such as Munger who had been farmhands, coaxing soft things from a hard earth, were drawn indoors to churn out bales of wire or rivets or some other replicated item in regimented fashion and predictable quantities. They peered into great fires, stamped out molds, and boiled with perspiration from the start of their shift until its conclusion twelve hours later. The hours were fixed, the outcome was known.

But with the certainty of mass employment and production came the sacrifice of an independent life. The factories felt like prisons, and increasingly young men Munger's age fantasized about the outside, daydreaming under the small, shut-tight windows that allowed only dabs of fractured light. Munger found himself particularly ill suited to the regimented factory life.

His father was an Ontario farmer who immigrated to Black Hawk County, Iowa, in 1859. Theodore wed Mary Jane Pattee, and they began their family in Iowa, with Louis born in 1864, amidst the war. Perhaps because of his Dutch pacifist ancestry, Theodore Munger fled the chaos of wartime America, bringing the family back to his native Canada shortly after Louis's birth.

The Mungers joined a rich and growing collection of exiles in southern Ontario, just across the Detroit River and the U.S. boundary. They included fugitive slaves, former British loyalists, displaced Native Americans, and the most recent exiles, the Civil War runaways and conscientious objectors. For the first ten years of his life, Birdie Munger grew up in a tolerant, diverse, and unusually democratic part of the world. A third of Colchester, one of Ontario's southernmost towns, consisted of black settlers. They'd come from Kentucky and points south, Colchester being the first cross-border stop on the Underground Railroad. In the distinctly egalitarian environs, the black settlers excelled, producing a slew of formidable achievers.

Theodore, a part-time inventor, and Mary brought their five children back to Detroit, where Theodore took work in the state patent office. A young boy such as Louis would have been exposed to one of the most dynamic eras in American ingenuity. In the time after the Civil War the entrepreneurial urge to create was seemingly infinite. There was the telephone, incandescent light, and Coca-Cola. Among the many successful, World's Fair-bound items that passed across Theodore Munger's desk were those of Elijah McCoy, a famous inventor who lived in the area. McCoy was awarded seventy patents, his most famous being a lubricating mechanism that prevented steam engines from overheating. Anywhere but the oddly color-blind border region between Ontario and Michigan, McCoy would've stood out for another reason, too: he was black.

What Birdie Munger kept with him on those long shuttered days in the factory was a sense that anyone, including himself, could do anything. Years later, when he met Taylor, began to coach him, hired him to work for his bicycle-frame-making company in Indianapolis, and then began to brag about him as a prospective world champion, it was as if he was foolishly naive and didn't understand the harsh, racially tinted lens through which all of America seemed to be staring-- and he didn't. He was from a much different part of the world, a mere few miles from the border that divided Canada from the United States but an incalculable distance away from the notion that a black man was born inferior to a white one. And he was an inventor's son. Inventors saw what was in front of them, not what was around them. What was in front of inventors, the greatest invention of the moment in a land suddenly teeming with them, was the bicycle. Given his young age, he wasn't ready to build them yet--but he did desperately want to race.

Early American bicycle racers such as Munger were a special breed. They lived and breathed bicycles, a small, ardent community of bachelors who would do anything to go faster and go anywhere to race. They were the spiritual ancestors to dragsters, supersonic pilots, free-falling BASE jumpers. It was like what Tom Wolfe wrote about Chuck Yeager and the first test pilots: "A fighter pilot soon found he wanted to associate only with other fighter pilots. Who else could understand the nature of the little proposition they were all dealing with? And what other subject could compare with it? So the pilot kept it to himself, along with an even more indescribable . . . an even more sinfully inconfessable . . . feeling of superiority, appropriate to him and to his kind, lone bearers of the right stuff."

They were doing what they loved--an indulgence, perhaps, yet irresistible--stepping into a delicious world stripped of everything but the moment-to-moment pursuit of a tingly feeling: how to make wheels spin like marbles on a slick gymnasium floor, or how to master the elemental forces so that riding a bike felt like plunging out of the sky, free-falling with both abandon and control, like an eagle dropping through the middle of a steep thermal. The feeling they craved was a descent, but the direction they had to move was across the earth, in touch with the nubby land and all the other elements that conspired to cause slowness.

From the Hardcover edition.

Free

July 1865

CITY OF LONDON

Atlantic Ocean

It glides along as though it were alive, and with

a smooth grace . . . everlasting and beautiful to behold.

--Scientific American

Magazine on the early pedal-powered bicycle

The South was still burning. Thousands of Confederate POWs remained in Union custody, having refused allegiance to their Yankee victors, and only a partial accounting of the 623,000 war dead had been made. It was a mere eight weeks after Appomattox and the end of the Civil War, but people were already on the move. The promise of America's large northern industrial cities, where work could be had and lives remade, triggered a massive response home and abroad.

The swell of humanity included a twenty-two-year-old French mechanic whose July transatlantic passage was notable because of what he steadfastly towed in a large clanging steamer trunk. Within were the unassembled parts of the first modern-era bicycle to land upon U.S. shores. Pierre Lallement, a baby-faced man with short legs and a penguin's stride, was the first of what would be a very long line of dreamers, schemers, and spectacular failures who would see in the beautiful symmetry of moving bicycle parts a new beginning. His wrought-iron frame didn't look like much, but he won a patent in 1866 and, more incredible still, he rode the thing, nobly taking to the green at New Haven, Connecticut, as a few rubbernecking strollers looked on.

Lallement's bicycle was, in truth, a giant advance that somehow eluded the best and brightest minds for generations, with "two wooden wheels, with iron tires, of nearly equal size, one before the other, surmounted by a wooden perch." The patent description, however, failed to emphasize the genius of the new design--foot pedals that would not just propel it but balance it. For the first time a rider could elevate his feet from terra firma (earlier versions were straddled and powered by hard, scooter-style pushes), drive his wherewithal into foot pedal cranks, and directly propel his earthly volume. One hundred and fifty years later it is the advance that a six-year-old who rides a bicycle for the first time remembers, the moment when the ground gives way, the wind sweetens, and nerve ends spark like dry tinder. It is the moment when doubt and fear release in a simple, fundamental expression of pungent emotion--something that sounds like "Wheeeee!"

Lallement didn't wait around long enough to see his bicycle gain acceptance--after a few years of queer looks and uneventful sales he glumly sailed back to France--but Americans did briefly experience a faddish burst of enthusiasm. It only lasted a year or two before they sharply turned on the contraption, dubbing the hard mechanical horse the "boneshaker." It was uncomfortable, unreliable, and rather awkward (the pedals were attached to the front wheel and not directly beneath the rider). Showcase races at outdoor courses did nothing to help the cause, as even supremely fit men on state-of-the art velocipedes (the precious-sounding term for the premodern steed) found walking speeds hard to best. It was not a racing bicycle. In a post-Civil War world where urban Americans had lofty expectations of a European-style enlightenment, the bike didn't measure up. By 1870, only five years after Lallement's dodgy transatlantic adventure, the primitive boneshaker was far more dead than alive.

Still, the sense among believers that they were in the proverbial ballpark and that the bicycle might be more than a fling stubbornly prevailed--especially in Europe, where English inventors one-upped their Parisian counterparts with the high-wheeler, the aptly described evolutionary follow-up to the boneshaker. With a lightweight hollow steel frame and cushioning seat spring, the British-made Ordinary was a far better vehicle than the boneshaker--her smooth, fast ride softened the old criticism--but the improvements came at the expense of what appeared to be life and limb. When the first ones were shipped to the United States in the late 1870s (unlike Europeans, it took a while for Americans to shake off the painful memory of its forebear) the new bicycle both enthralled and terrified Victorian America. Of his own experiences the early bicycling advocate Charles E. Pratt wrote, "It runs, it leaps, it rears and writhes; it is in infinite restless motion, like a bundle of sensitive nerves; it is beneath its rider like a thing of life."

The rider was a stratospheric eight feet off the ground, making a first encounter distressingly akin to sitting atop a moving lamppost. Children were particularly endangered. When Major Taylor was first starting to race, the old-timers initiated him by placing him atop the towering Ordinary, then sat back to watch and wait for the expected fall. The pedals were attached to the front wheel, the way they are on a tricycle. Unlike a tricycle, a Sisyphean thrust was required to budge the four-foot-diameter, hard-tired wheel. Brakes were primitive (or nonexistent), and a gentlemanly upright posture made the slightest puff of wind a worthy opponent. Literally and figuratively, a leap of faith was necessary to balance on tiny pedals and grossly dissimilar-sized wheels. The high-wheeler virtually ensured that a stalwart, risk-averse citizen who adored certainty, and for whom dignity was zealously sought in every waking moment, would be monstrously disappointed.

A technical explanation didn't alleviate the concern. Wheels, one small, the other enormous, were aligned so that the oversized rim supported the rider's center of gravity. Once in motion, scientists observed, "the physical forces generated by the rotation of the wheels produced a self steering effect." The technical term was precession. Perversely, the stabilizing force that kept one upright increased the faster you went. In other words, you had to risk life in the hope of saving it. The high-wheel bicycle, the popular frame design in America prior to 1890, didn't defy physical law, but it did challenge it.

Despite these immense challenges, a 19th-century person's motivation to learn to ride, once sufficiently teased by seeing others in motion, was unparalleled. Buttoned-up, pickled Victorians had too long stifled the pulsing in their chests. They desperately needed an emotional outlet; they wanted to flush their cheeks with color, expand their lungs with air, and swiftly glide from town to town. As a Nickell writer explained, every man was born with some of the "trick instinct." He meant that there was something innate and unseen, like luxurious black oil beneath the earth's still granite mantle, that lay untapped in everyone. Soon America seemed hell-bent on probing the great unknown. Thus, there were a multitude of horrible accidents, but also the kind of magnificence and magic the boneshaker never afforded. Wrote H. G. Wells in his fictional narrative of a neophyte's experience in the English countryside, "[Hoopdriver] wheeled his machine up Putney Hill, and his heart sang within him." Indeed, hearts sang and bicycles led the lovelorn to the bucolic, the exotic, and reputation-making hero climbs such as Ford Hill in Philadelphia. Those who were previously sedentary and waiting tremulously for the inevitable ravages of illness to overtake them flew into delighted, freewheeling motion. Lightness shone through the bleak day-to-day. Underdogs rejoiced.

Unlike in the boneshaker era, being a spectator was nearly as fun. In the summer of 1878, the same year both Taylor and McFarland were born, a former shoe manufacturer named Albert Pope launched his Columbia brand--the first American-manufactured high-mount-- by sponsoring the country's first race on American-made bicycles. It was a precocious moment, bicycles being the hoped-for leader of a burgeoning postwar renaissance in physical sports. There was excited talk of the newly addictive "Athletic Impulse," of the way sports glorified our culture and ennobled the men who gamely partook. A keenness for outdoor sports had emerged, one that made the rising generation "big and lusty and pleasant to look at." Soon records were being broken: all kinds, all places. Neither foot racers nor most fleet Thoroughbreds could compare. In a span of only a few years the mile record, the benchmark for true, life-changing speed, was reduced from six minutes to less than three.

Pope's Boston Back Bay velodrome, site of that first American-style bicycle extravaganza, consisted of a planked cycling track inside a mammoth 320-foot-long tent. For several weeks high-wheel racers from Boston and imports from England and France hazarded gale-force winds and bitter Thanksgiving cold, racing distances up to 100 miles on the ten-laps-to-the-mile track. The French champion Charles Terront, an incorrigible ladies' man, wore snug white flannel knee breeches, blue stockings, and a silk ascot. His English rival quoted Shakespeare and went by the racing nom de guerre "Happy Jack." There was an American entry--an ancestral link to Major Taylor, Floyd McFarland, and even Lance Armstrong. Unfortunately, he wasn't deemed important enough to be mentioned by name in the press. Each day they rode with brave, unchecked abandon, their bicycles weighing a thumping thirty pounds.

Fans warmed to the activity in a way that inspired Pope and his rival manufacturers. They saw the potential of the market and began to ramp up. When the American neophyte hit a pole at a top-end speed of 20 mph, an amused London visitor described the bone-snapping collision as "an aerial flight to Mother Earth via the over-the-handles route."

Cycling as an American spectator sport had the necessary toehold.

Louis de Franklin Munger, a young hawk-nosed Detroit lad working in a blind-making factory, was one of the thousands of adventure-seeking American men swept into the craze. He had thick, pugnacious features but soft green eyes and almost aboriginal high cheekbones. Heretofore, the factories were the spectacle of his generation. The massive brick establishments, running along America's wide riverbanks, were symbols of progress and power and modernization. The shoppy smell of coal and coke choked the air; the homes nearby were blackened with a sooty film. On the factory floor the cacophony of surfacing machines, water pumps, air compressors, hammers, and pneumatic tools made it impossible to hear--the vibration saturated the body and didn't ever fully dissipate, not even in sleep. Young men such as Munger who had been farmhands, coaxing soft things from a hard earth, were drawn indoors to churn out bales of wire or rivets or some other replicated item in regimented fashion and predictable quantities. They peered into great fires, stamped out molds, and boiled with perspiration from the start of their shift until its conclusion twelve hours later. The hours were fixed, the outcome was known.

But with the certainty of mass employment and production came the sacrifice of an independent life. The factories felt like prisons, and increasingly young men Munger's age fantasized about the outside, daydreaming under the small, shut-tight windows that allowed only dabs of fractured light. Munger found himself particularly ill suited to the regimented factory life.

His father was an Ontario farmer who immigrated to Black Hawk County, Iowa, in 1859. Theodore wed Mary Jane Pattee, and they began their family in Iowa, with Louis born in 1864, amidst the war. Perhaps because of his Dutch pacifist ancestry, Theodore Munger fled the chaos of wartime America, bringing the family back to his native Canada shortly after Louis's birth.

The Mungers joined a rich and growing collection of exiles in southern Ontario, just across the Detroit River and the U.S. boundary. They included fugitive slaves, former British loyalists, displaced Native Americans, and the most recent exiles, the Civil War runaways and conscientious objectors. For the first ten years of his life, Birdie Munger grew up in a tolerant, diverse, and unusually democratic part of the world. A third of Colchester, one of Ontario's southernmost towns, consisted of black settlers. They'd come from Kentucky and points south, Colchester being the first cross-border stop on the Underground Railroad. In the distinctly egalitarian environs, the black settlers excelled, producing a slew of formidable achievers.

Theodore, a part-time inventor, and Mary brought their five children back to Detroit, where Theodore took work in the state patent office. A young boy such as Louis would have been exposed to one of the most dynamic eras in American ingenuity. In the time after the Civil War the entrepreneurial urge to create was seemingly infinite. There was the telephone, incandescent light, and Coca-Cola. Among the many successful, World's Fair-bound items that passed across Theodore Munger's desk were those of Elijah McCoy, a famous inventor who lived in the area. McCoy was awarded seventy patents, his most famous being a lubricating mechanism that prevented steam engines from overheating. Anywhere but the oddly color-blind border region between Ontario and Michigan, McCoy would've stood out for another reason, too: he was black.

What Birdie Munger kept with him on those long shuttered days in the factory was a sense that anyone, including himself, could do anything. Years later, when he met Taylor, began to coach him, hired him to work for his bicycle-frame-making company in Indianapolis, and then began to brag about him as a prospective world champion, it was as if he was foolishly naive and didn't understand the harsh, racially tinted lens through which all of America seemed to be staring-- and he didn't. He was from a much different part of the world, a mere few miles from the border that divided Canada from the United States but an incalculable distance away from the notion that a black man was born inferior to a white one. And he was an inventor's son. Inventors saw what was in front of them, not what was around them. What was in front of inventors, the greatest invention of the moment in a land suddenly teeming with them, was the bicycle. Given his young age, he wasn't ready to build them yet--but he did desperately want to race.

Early American bicycle racers such as Munger were a special breed. They lived and breathed bicycles, a small, ardent community of bachelors who would do anything to go faster and go anywhere to race. They were the spiritual ancestors to dragsters, supersonic pilots, free-falling BASE jumpers. It was like what Tom Wolfe wrote about Chuck Yeager and the first test pilots: "A fighter pilot soon found he wanted to associate only with other fighter pilots. Who else could understand the nature of the little proposition they were all dealing with? And what other subject could compare with it? So the pilot kept it to himself, along with an even more indescribable . . . an even more sinfully inconfessable . . . feeling of superiority, appropriate to him and to his kind, lone bearers of the right stuff."

They were doing what they loved--an indulgence, perhaps, yet irresistible--stepping into a delicious world stripped of everything but the moment-to-moment pursuit of a tingly feeling: how to make wheels spin like marbles on a slick gymnasium floor, or how to master the elemental forces so that riding a bike felt like plunging out of the sky, free-falling with both abandon and control, like an eagle dropping through the middle of a steep thermal. The feeling they craved was a descent, but the direction they had to move was across the earth, in touch with the nubby land and all the other elements that conspired to cause slowness.

From the Hardcover edition.