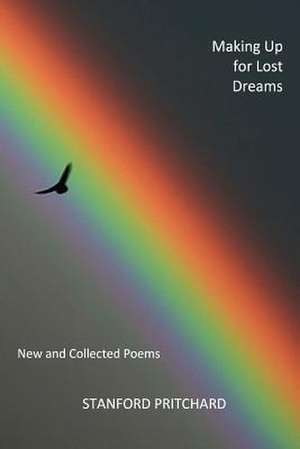

Making Up for Lost Dreams

Autor Pritchard, MR Stanforden Limba Engleză Paperback

Preț: 73.23 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 110

Preț estimativ în valută:

14.01€ • 14.54$ • 11.71£

14.01€ • 14.54$ • 11.71£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 24 februarie-10 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781494755188

ISBN-10: 1494755181

Pagini: 230

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 12 mm

Greutate: 0.31 kg

Editura: CREATESPACE

ISBN-10: 1494755181

Pagini: 230

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 12 mm

Greutate: 0.31 kg

Editura: CREATESPACE