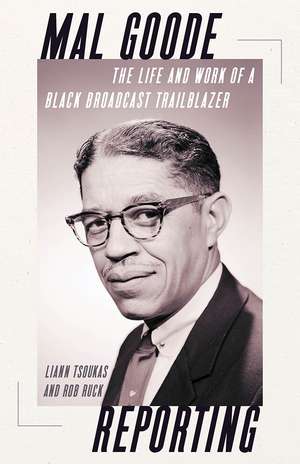

Mal Goode Reporting: The Life and Work of a Black Broadcast Trailblazer.

Autor Liann Tsoukas, Rob Rucken Limba Engleză Hardback – 23 apr 2024

Preț: 212.93 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 319

Preț estimativ în valută:

40.74€ • 42.63$ • 33.85£

40.74€ • 42.63$ • 33.85£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 13-27 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780822948223

ISBN-10: 0822948222

Pagini: 400

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 46 mm

Greutate: 0.74 kg

Editura: University of Pittsburgh Press

Colecția University of Pittsburgh Press

ISBN-10: 0822948222

Pagini: 400

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 46 mm

Greutate: 0.74 kg

Editura: University of Pittsburgh Press

Colecția University of Pittsburgh Press

Recenzii

“This is a stellar biography of an important figure in the history of African American and US television journalism. It also illuminates the complicated process by which a working-class Black man made the transition from wage-earning proletariat to salaried member of the African American professional class.”

—Joseph Trotter, Carnegie Mellon University

—Joseph Trotter, Carnegie Mellon University

Notă biografică

Liann Tsoukas teaches history at the University of Pittsburgh, where her courses focus on African American history, US surveys, contemporary US history, and gender and sport. Tsoukas directs the sport studies certificate and serves as an assistant dean as well as the History Department’s director of undergraduate studies. She has been recognized with several honors including the 2023 Chancellor’s Distinguished Teaching Award.

Rob Ruck is a historian at the University of Pittsburgh, where he teaches and writes about sport. He focuses on how people use sport to tell a collective story about who they are to themselves and the world. He is the author of Tropic of Football: The Long and Perilous Journey of Samoans to the NFL, Raceball: How the Major Leagues Colonized the Black and Latin Game, and Rooney: A Sporting Life, among other titles. His documentaries Kings on the Hill: Baseball’s Forgotten Men and The Republic of Baseball: Dominican Giants of the American Game appeared on PBS.

Rob Ruck is a historian at the University of Pittsburgh, where he teaches and writes about sport. He focuses on how people use sport to tell a collective story about who they are to themselves and the world. He is the author of Tropic of Football: The Long and Perilous Journey of Samoans to the NFL, Raceball: How the Major Leagues Colonized the Black and Latin Game, and Rooney: A Sporting Life, among other titles. His documentaries Kings on the Hill: Baseball’s Forgotten Men and The Republic of Baseball: Dominican Giants of the American Game appeared on PBS.

Extras

EXCERPT FROM THE INTRODUCTION TO MAL GOODE REPORTING

On October 28, 1962, Americans were stunned when broadcasters interrupted scheduled programing to report the unthinkable. The world was careening toward a nuclear confrontation. Just six days before, President John F. Kennedy had addressed the nation, warning that aerial surveillance of Cuba, the Caribbean island just ninety miles from Florida, confirmed the presence of a Soviet nuclear strike capability. The United States, he announced, had issued an ultimatum to the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics to remove those missiles. After days of back-channel talks, UN Security Council sessions, and Cuban anti-aircraft downing a U-2 aircraft, the Cold War confrontation was about to climax.

As US warships raced to intercept Soviet vessels heading for Cuban waters, Americans perched on couches and kitchen chairs, watching the crisis unfold on television and listening to radio updates. Schoolchildren practiced “duck and cover” drills and the nation’s armed forces mobilized. When ABC broke into programming with updates on the standoff, there was a new face on the screen and a new voice on the radio. A tall, distinguished-looking African American called Mal Goode calmly delivered one report after another with the United Nations building looming behind him. Never before had the world come so close to nuclear warfare, and never before had a Black man conveyed breaking news for a national network. The threat of war soon faded, but Mal Goode wasn’t going anywhere.

Goode made history that day, and the television and radio spots he delivered during the Cuban Missile Crisis were a prologue to his television career, not a one-off. A fixture on ABC News for the next decade, he chipped away at one of media’s most stubbornly segregated formats by interpreting the news for a national audience. Goode’s sense of mission was clear: to explain the racial currents of a nation in turmoil, inject an African American perspective into the conversation, serve his profession, and address all TV viewers.

But Goode’s dramatic career launch was inadvertent. ABC’s decision in the summer of 1962 was simply to hire a Black correspondent. Network executives had not thought through what a barrier-breaking national correspondent would do on ABC, much less how and why his presence would matter. The hire was no guarantee that Goode would be on air. His assignment to the United Nations, where most correspondents remained tucked away on what was considered one of least interesting beats for the TV audience, meant that viewers might not catch a glimpse of the historic hire. However, the United Nations was central during the confrontation over Cuba for thirteen harrowing days in October 1962. With tensions rising, ABC news director Jim Hagerty was unable to reach the network’s vacationing chief UN correspondent John McVane. Hagerty did not anticipate that Mal Goode, on the job for less than two months, would easily slide into the role played by McVane, a legendary foreign correspondent. But Goode did deliver seventeen on-air reports. He charted the contours of the crisis and the relief of resolution to a weary audience with a calm cool-headed delivery.

ABC, then lagging behind CBS and NBC in the ratings, had gambled that Goode, the grandson of enslaved people, could attract an African American audience without alienating white viewers. His success was all the more extraordinary given his personal saga. Before Mal Goode’s parents met, they came north separately from two different parts of Virginia during the Great Migration. Mal was born in Virginia and the family frequently traveled between there and Pittsburgh, but he had lived in Pittsburgh from the age of eight and worked there until 1962. From a radio studio on the city’s Hill District, which Claude McKay had dubbed the crossroads of the world, Goode’s basso profundo voice resonated throughout western Pennsylvania. Challenging segregation wherever he saw it and contradicting police accounts of Black men who died in custody, Goode became Black Pittsburgh’s paladin. He celebrated the victories of those who broke through by roaring “And the walls came tumbling down!” But Goode chafed at his own inability to break into television until his friend Jackie Robinson dared ABC to give him a chance.

Goode’s career, first in Pittsburgh and then with a national network, put him center stage as the civil rights campaign to dismantle segregation reached a tipping point during the 1950s and 1960s. His coverage was tough but fair. Willing to confront the likes of Alabama governor George Wallace and leaders of the American Nazi Party, Goode broke ground in broadcast journalism. He was on the street during the urban rebellions of the 1960s, after Malcolm X’s assassination, and during Martin Luther King Jr.’s final campaign. Whether covering African independence struggles, national political conventions, or Atlanta, Georgia, which he profiled in a 1969 documentary as a city “too busy to hate,” he brought his take on the struggle for equality to a national audience.

On October 28, 1962, Americans were stunned when broadcasters interrupted scheduled programing to report the unthinkable. The world was careening toward a nuclear confrontation. Just six days before, President John F. Kennedy had addressed the nation, warning that aerial surveillance of Cuba, the Caribbean island just ninety miles from Florida, confirmed the presence of a Soviet nuclear strike capability. The United States, he announced, had issued an ultimatum to the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics to remove those missiles. After days of back-channel talks, UN Security Council sessions, and Cuban anti-aircraft downing a U-2 aircraft, the Cold War confrontation was about to climax.

As US warships raced to intercept Soviet vessels heading for Cuban waters, Americans perched on couches and kitchen chairs, watching the crisis unfold on television and listening to radio updates. Schoolchildren practiced “duck and cover” drills and the nation’s armed forces mobilized. When ABC broke into programming with updates on the standoff, there was a new face on the screen and a new voice on the radio. A tall, distinguished-looking African American called Mal Goode calmly delivered one report after another with the United Nations building looming behind him. Never before had the world come so close to nuclear warfare, and never before had a Black man conveyed breaking news for a national network. The threat of war soon faded, but Mal Goode wasn’t going anywhere.

Goode made history that day, and the television and radio spots he delivered during the Cuban Missile Crisis were a prologue to his television career, not a one-off. A fixture on ABC News for the next decade, he chipped away at one of media’s most stubbornly segregated formats by interpreting the news for a national audience. Goode’s sense of mission was clear: to explain the racial currents of a nation in turmoil, inject an African American perspective into the conversation, serve his profession, and address all TV viewers.

But Goode’s dramatic career launch was inadvertent. ABC’s decision in the summer of 1962 was simply to hire a Black correspondent. Network executives had not thought through what a barrier-breaking national correspondent would do on ABC, much less how and why his presence would matter. The hire was no guarantee that Goode would be on air. His assignment to the United Nations, where most correspondents remained tucked away on what was considered one of least interesting beats for the TV audience, meant that viewers might not catch a glimpse of the historic hire. However, the United Nations was central during the confrontation over Cuba for thirteen harrowing days in October 1962. With tensions rising, ABC news director Jim Hagerty was unable to reach the network’s vacationing chief UN correspondent John McVane. Hagerty did not anticipate that Mal Goode, on the job for less than two months, would easily slide into the role played by McVane, a legendary foreign correspondent. But Goode did deliver seventeen on-air reports. He charted the contours of the crisis and the relief of resolution to a weary audience with a calm cool-headed delivery.

ABC, then lagging behind CBS and NBC in the ratings, had gambled that Goode, the grandson of enslaved people, could attract an African American audience without alienating white viewers. His success was all the more extraordinary given his personal saga. Before Mal Goode’s parents met, they came north separately from two different parts of Virginia during the Great Migration. Mal was born in Virginia and the family frequently traveled between there and Pittsburgh, but he had lived in Pittsburgh from the age of eight and worked there until 1962. From a radio studio on the city’s Hill District, which Claude McKay had dubbed the crossroads of the world, Goode’s basso profundo voice resonated throughout western Pennsylvania. Challenging segregation wherever he saw it and contradicting police accounts of Black men who died in custody, Goode became Black Pittsburgh’s paladin. He celebrated the victories of those who broke through by roaring “And the walls came tumbling down!” But Goode chafed at his own inability to break into television until his friend Jackie Robinson dared ABC to give him a chance.

Goode’s career, first in Pittsburgh and then with a national network, put him center stage as the civil rights campaign to dismantle segregation reached a tipping point during the 1950s and 1960s. His coverage was tough but fair. Willing to confront the likes of Alabama governor George Wallace and leaders of the American Nazi Party, Goode broke ground in broadcast journalism. He was on the street during the urban rebellions of the 1960s, after Malcolm X’s assassination, and during Martin Luther King Jr.’s final campaign. Whether covering African independence struggles, national political conventions, or Atlanta, Georgia, which he profiled in a 1969 documentary as a city “too busy to hate,” he brought his take on the struggle for equality to a national audience.