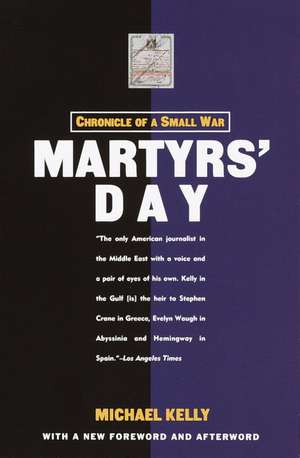

Martyrs' Day: Chronicle of a Small War

Autor Michael Kellyen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 noi 2001

Preț: 80.63 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 121

Preț estimativ în valută:

15.43€ • 16.15$ • 12.84£

15.43€ • 16.15$ • 12.84£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400030361

ISBN-10: 1400030366

Pagini: 384

Ilustrații: 1 MAP

Dimensiuni: 137 x 204 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.31 kg

Ediția:Vintage Books.

Editura: Vintage Books USA

ISBN-10: 1400030366

Pagini: 384

Ilustrații: 1 MAP

Dimensiuni: 137 x 204 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.31 kg

Ediția:Vintage Books.

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Extras

MARTYRS' DAY

BAGHDAD IS RICH IN MONUMENTS to the dead of war. They are, excepting the Leader's many palaces, by far the most impressive pieces of architecture in the city. The most peculiar one is The Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, a pavilion of polished dark-red granite over which hangs a giant upside-down metal clamshell hundreds of feet in diameter. A visitor walks up a long, broad ramp of gray stone that leads, as it were, into the belly of the clam. To one side is a smallish ziggurat, modeled on the ancient Tower of Amara, but in fact as trashily modern as a Burger King, with bright red, green, and black tiles crawling up and down its sides. A square hole in the granite under the center of the clam leads to a staircase, which descends two stories to debouch into a round, windowless room.

The walls of the room, cambered inward to follow the line of the shell, are made of stainless steel and lined with poster-size photographs of the Leader at war: reviewing troops, tasting soup at a field kitchen, firing a rocket-propelled grenade, shaking hands with soldiers, regarding a howitzer. In between and in front of the photographs are glass display cases. Most of the cases contain weapons left over from one or another episode of large-scale killing. Killing has been a more or less continual preoccupation in Iraq since the Great Arab Revolt of 1916-1918. There have been twenty-three coups or attempted coups, five large politico-tribal revolts or massacres, and the country has been involved to one degree or another in eight wars. In a counterclockwise sequence, the displays make up a rough visual history of Iraq's unhappy progression, beginning with the shields, spears, and swords of early Ottoman days, moving on to the elaborate pistols and blunderbusses and hand-tooled Berber long guns of the nineteenth century, then to the sticks, shovels, hatchets, and clubs of the early-twentieth-century anti-British uprising, and so on into the modern era. Each display is labeled with a neat, hand-lettered placard:

"Collection of mechanical rifles used by the Iraqi brave army in some earlier years.

"Thompson machine gun, American-made, gained among the booty in the battle against the Zionist enemy in 1948."

"Machine guns used by a group of Arab Baath Socialist Party Revolutionaries in the operation of blowing [sic] the tyrant Abd al-Karim Qasim on 7th October, 1959." (Twenty-two-year-old Saddam Hussein, the future Leader, was among the participants in the failed attack on air force officer Qasim, who had taken power in a coup against the British-supported Iraqi monarchy the year before. According to his official biography, Saddam received a bullet in the leg, which a friend cut out with a razor blade.)

"Part of Israeli (Mirage) plane shot down by our great forces in 1967 in the H3 area."

On one of the longer glass cases, there is a placard with the word "Martyrs" in a squirm of red Arabic script. Inside are the uniforms worn by various Iraqi soldiers or pilots at the time of their deaths. The uniforms lie flat and are slightly wrinkled. Without bodies to fill them they seem, like medieval suits of armor, too small and somehow false. They have holes in them, and the holes are ringed with rust-colored stains.

A quarter-mile or so down the highway from the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier is the Hands of Victory Pavilion, built in 1984 to celebrate an exceptionally bloody triumph in the most recent Iraqi war save one, the long and awful fight with Iran. The pavilion is a terrible thing. It is approached via a wide asphalt boulevard lined by unusually ugly lampposts, oversized globes set on spindly stalks. The boulevard runs a distance of several city blocks between two matching sets of giant forearms, which rise directly out of the asphalt, one on each side of the road, and loom high into the air, ending in hands clenched in fists. The Leader's own arms and hands were the models for these, the official legend says. The arms are thick with twined ropes of muscle and the fists are the big-knuckled hams of a back-alley brawler; nose-breaker, teeth-smasher fists. Each fist holds a scimitar, and the curved blades cross high above the avenue, so that soldiers may parade, and tourists may stroll, under their protective arches.

At the bases of the arms are huge metal nets, like fishing seines, filled with helmets. The nets are long, pendulous, banana-shaped things, and they have been overstuffed, so the helmets burst obscenely out of their bottom ends onto the ground. What is terrible about the Victory Pavilion lies in this sight and in something all who see it know: the helmets are the real helmets of real dead men, collected on the battlefield from the heads of enemy Iranians. There are thousands of helmets. They are a diverse bunch--American GI models from the Second World War, broad-rimmed doughboy's hats from the First, even a few crested parade-dress hats of a Kaiser Wilhelm style--and battered, full of scars and dents and ragged-edged holes. As they spill out of each net, they make mounds that cascade down onto the avenue,where they are cemented in an artful jumble. Some are set more formally, in rows, upright and mostly buried, but with their tops peeking out like gumdrops in a Candyland road. The rows traverse the road, so that it is impossible to enter the pavilion without driving or walking over the helmets of the dead.

The most traditional, and the most benevolent in spirit, of the major monuments in Baghdad is the Monument of Saddam's Qadisiyyah Martyrs. The war with Iran was called Qadisiyyah Saddam, after the seventh-century Battle of Qadisiyyah, in which the Arabs drove the Persians from Mesopotamia, and the monument has come to be a sort of all-purpose marker for everyone killed one way or another in service to the Leader. It begins on a horizontal plane, an expanse of gray granite slabs set in a block-long avenue lined with flags and date palms. The avenue leads to the vertical center, a giant blue egg set in a field of white marble and split longitudinally in half. The halves are slightly staggered so that they do not directly oppose each other. They are meant to suggest the dome of a mosque, open to the heavens, to allow the souls of the dead and the prayers of the living to reach God.

On December 1 of every year, the people of Iraq honor their war dead in what is known by decree of the Leader as Martyrs' Day. The focal point is the martyrs' monument, where the principal, official ceremony is held. At a quarter to ten on the morning of December 1, 1991--an unsuitable morning, sunny and blue and unseasonably, sweetly warm--a few hundred people were lined up in patient quietude before the heavy black steel security fence that guards the entrance. The fence is set on wheels in tracks, and opened and shut by electrical impulse. It was a professional crowd of mourners: soldiers, schoolchildren, government workers, and party hacks. Bureaucrats fussed around and through the crowd, herding everyone into just-so order. They were from the Ministry of Information and Culture, and they are known as "minders." As a foreigner, I had a minder assigned just to me, and he hovered at my shoulder like a hummingbird, nervous and eager to please.

In the vast and cruel hierarchy of the Iraqi state, minders are important enough to be disliked by their colleagues and charges, but not important enough to be respected or feared. The spies that matter, the sleek young louts of the Mukhabarat, have the power to torture and kill, and act like it. They wear sunglasses and black vinyl jackets and pleated Italian trousers, and swagger about Baghdad like Toonland gunsels. Minders wear the genteel-shabby suits of the clerking class. Formalized snitches, classroom monitors, they inspire only resentment and sneers behind their backs. They suffer from low self-esteem. In three trips to Iraq, I never learned their proper title. Everyone called them minders, and they even called themselves by this mildly deprecatory term: "Hello, I am your minder today," or "If you are going to go to the market, you must remember to take a minder."

At ten o'clock, the two long center sections of the fence jerked apart with a grinding, clanking rumble, and after a moment's hesitation the crowd moved forward, slowly, silently, up the walk to the big blue eggshells. At the front were the guests of honor, two war widows and an orphan. The widows were suitably dressed in black, but the child wore a bright pink party frock, puffed up with layers of frilly slips underneath.

Behind them came several platoons of boys dressed as soldiers, in crisp fatigues of blue or tan cloth stamped with a camouflage pattern. They wore gold epaulets on their narrow shoulders, and pink and white scarves around their skinny necks. They were no more than ten or eleven years old, and they were members of al-Talaia--the Vanguards--the state organization for citizens between the ages of ten and fifteen. Political indoctrination in Iraq actually begins when children enter school at the age of five or six, but al-Talaia is the first organized politico-military group to which one can belong. The young troops of the Vanguard learn to march and to follow orders, and to serve as junior agents of the state, filing reports on their peers and, on occasion, parents.

The little troopers marched up the walk as a unit, properly, with a childish semblance of military discipline, pumping their arms and swinging their legs in goose-stepping exuberance. Some carried bright paper parasols, which they twirled in ragged coordination. They chanted as they marched: "Long life to the Baath Party! Long life to Saddam Hussein!"

Behind the little Vanguard boys were similar platoons of little Vanguard girls, in blue uniform dresses, carrying flowers, walking along primly and properly, as if they might, by example, teach the boys how to behave. Trailing them was a sort of Toddlers' Auxiliary, children culled from various kindergartens and pre-kindergartens. There was one small boy I liked especially. He was tricked out in a miniature suit of black formal wear, with tails and a bow tie and a red sateen vest. He could not stay still; he danced all over the place.

At the base of the dome, where the gray granite gave way to white marble, the crowd coming in merged with the honor guard already in place. There were half a dozen units, all in parade dress, gaudy and grand and gleaming in the morning sun. The Republican Guards were the most glorious, in uniforms as fine as Victoria's own fusiliers, red tunics with blue sashes, and tall topees, with gold chin straps below and gold tassels stirring in the breeze above. They played drums and horns and clarinets, ushering in the mourners with a tune of a vaguely Sousa-ish nature. "It is a national song, very popular," my minder said. "It is called 'We Welcome the National War.'"

A couple of hundred feet of red carpet had been unrolled up the center of the approach to the pale little flame--almost invisible in the sunlight--in between the eggshells, and the assemblage gathered at the foot of this. Everyone was orderly. The only people making any noise were the musicians of the Republican Guard and the boys of al-Talaia, who had taken up the traditional song on these occasions.

"With our blood, with our souls, we sacrifice for Saddam," they trilled in their pretty, light boy-voices.

The ceremony did not take long. First, six middle-aged men in suits from the Arab Baath Socialist Party walked up and laid down a wreath in front of the small gas flame that burned from a hole set in a granite circle between the two halves of the dome. Then four middle-aged men in suits from the Iraqi National Student Union walked up and laid down a wreath. Then five men in suits and one woman in a suit from the Iraqi National Teachers' Union, etc.

As each delegation approached the end of the carpet, a brigadier general and two soldiers stepped in to escort them. The soldiers flanked the head of the delegation, who carried the wreath, and the three of them walked the last few steps to the flame with a properly slow, funereal gait. When the head of the delegation laid down the wreath, the soldiers did a little dance. Facing the monument, they brought their right legs up waist-high, and then stomped them down, made a half turn so they faced each other, and did it again, then executed a neat half circle to change sides, and a third high step-stomp. Facing front again, they did two rapid stomps, first with the left leg, then with the right; then an about face and a final stomp before the walk back down the carpet.

And on and on it went, all of a bleak, bleached sameness, each party trudging up, laying down its wreath as the honor guard jigged, trudging back: the General Secretariat of Iraqi Economic Advisers, the Iraqi Geologists' Union, the Iraqi Doctors' Union, the Union of Employees of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Iraqi Women's Federation, the Iraqi Friends of the Children Association, the General Federation of Arab Women, the Union of Employees of the Ministry of Information and Culture. As each group approached, the minder read its name off the wreath and whispered it in my ear. Once, he got excited. "Here is a group coming up that has no name on its wreath," he said. The oddity of this caused him to fall prey to a sudden false and wild hope. "Maybe it is just citizens." But then the breeze blew away a palm leaf that had been hiding a tag. "Oh," said the minder. "No. It is the Union of Employees of the Ministry of the Interior."

He seemed a little embarrassed, but the paucity of ordinary citizens was hardly his fault. Over the last quarter century, the Leader had killed off, one way or another, an astonishing number of the ordinary citizens of Iraq, and many of those left living in the winter of 1991 were too crippled or drunk or hungry to gin up much enthusiasm for the celebration of their condition.

BAGHDAD IS RICH IN MONUMENTS to the dead of war. They are, excepting the Leader's many palaces, by far the most impressive pieces of architecture in the city. The most peculiar one is The Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, a pavilion of polished dark-red granite over which hangs a giant upside-down metal clamshell hundreds of feet in diameter. A visitor walks up a long, broad ramp of gray stone that leads, as it were, into the belly of the clam. To one side is a smallish ziggurat, modeled on the ancient Tower of Amara, but in fact as trashily modern as a Burger King, with bright red, green, and black tiles crawling up and down its sides. A square hole in the granite under the center of the clam leads to a staircase, which descends two stories to debouch into a round, windowless room.

The walls of the room, cambered inward to follow the line of the shell, are made of stainless steel and lined with poster-size photographs of the Leader at war: reviewing troops, tasting soup at a field kitchen, firing a rocket-propelled grenade, shaking hands with soldiers, regarding a howitzer. In between and in front of the photographs are glass display cases. Most of the cases contain weapons left over from one or another episode of large-scale killing. Killing has been a more or less continual preoccupation in Iraq since the Great Arab Revolt of 1916-1918. There have been twenty-three coups or attempted coups, five large politico-tribal revolts or massacres, and the country has been involved to one degree or another in eight wars. In a counterclockwise sequence, the displays make up a rough visual history of Iraq's unhappy progression, beginning with the shields, spears, and swords of early Ottoman days, moving on to the elaborate pistols and blunderbusses and hand-tooled Berber long guns of the nineteenth century, then to the sticks, shovels, hatchets, and clubs of the early-twentieth-century anti-British uprising, and so on into the modern era. Each display is labeled with a neat, hand-lettered placard:

"Collection of mechanical rifles used by the Iraqi brave army in some earlier years.

"Thompson machine gun, American-made, gained among the booty in the battle against the Zionist enemy in 1948."

"Machine guns used by a group of Arab Baath Socialist Party Revolutionaries in the operation of blowing [sic] the tyrant Abd al-Karim Qasim on 7th October, 1959." (Twenty-two-year-old Saddam Hussein, the future Leader, was among the participants in the failed attack on air force officer Qasim, who had taken power in a coup against the British-supported Iraqi monarchy the year before. According to his official biography, Saddam received a bullet in the leg, which a friend cut out with a razor blade.)

"Part of Israeli (Mirage) plane shot down by our great forces in 1967 in the H3 area."

On one of the longer glass cases, there is a placard with the word "Martyrs" in a squirm of red Arabic script. Inside are the uniforms worn by various Iraqi soldiers or pilots at the time of their deaths. The uniforms lie flat and are slightly wrinkled. Without bodies to fill them they seem, like medieval suits of armor, too small and somehow false. They have holes in them, and the holes are ringed with rust-colored stains.

A quarter-mile or so down the highway from the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier is the Hands of Victory Pavilion, built in 1984 to celebrate an exceptionally bloody triumph in the most recent Iraqi war save one, the long and awful fight with Iran. The pavilion is a terrible thing. It is approached via a wide asphalt boulevard lined by unusually ugly lampposts, oversized globes set on spindly stalks. The boulevard runs a distance of several city blocks between two matching sets of giant forearms, which rise directly out of the asphalt, one on each side of the road, and loom high into the air, ending in hands clenched in fists. The Leader's own arms and hands were the models for these, the official legend says. The arms are thick with twined ropes of muscle and the fists are the big-knuckled hams of a back-alley brawler; nose-breaker, teeth-smasher fists. Each fist holds a scimitar, and the curved blades cross high above the avenue, so that soldiers may parade, and tourists may stroll, under their protective arches.

At the bases of the arms are huge metal nets, like fishing seines, filled with helmets. The nets are long, pendulous, banana-shaped things, and they have been overstuffed, so the helmets burst obscenely out of their bottom ends onto the ground. What is terrible about the Victory Pavilion lies in this sight and in something all who see it know: the helmets are the real helmets of real dead men, collected on the battlefield from the heads of enemy Iranians. There are thousands of helmets. They are a diverse bunch--American GI models from the Second World War, broad-rimmed doughboy's hats from the First, even a few crested parade-dress hats of a Kaiser Wilhelm style--and battered, full of scars and dents and ragged-edged holes. As they spill out of each net, they make mounds that cascade down onto the avenue,where they are cemented in an artful jumble. Some are set more formally, in rows, upright and mostly buried, but with their tops peeking out like gumdrops in a Candyland road. The rows traverse the road, so that it is impossible to enter the pavilion without driving or walking over the helmets of the dead.

The most traditional, and the most benevolent in spirit, of the major monuments in Baghdad is the Monument of Saddam's Qadisiyyah Martyrs. The war with Iran was called Qadisiyyah Saddam, after the seventh-century Battle of Qadisiyyah, in which the Arabs drove the Persians from Mesopotamia, and the monument has come to be a sort of all-purpose marker for everyone killed one way or another in service to the Leader. It begins on a horizontal plane, an expanse of gray granite slabs set in a block-long avenue lined with flags and date palms. The avenue leads to the vertical center, a giant blue egg set in a field of white marble and split longitudinally in half. The halves are slightly staggered so that they do not directly oppose each other. They are meant to suggest the dome of a mosque, open to the heavens, to allow the souls of the dead and the prayers of the living to reach God.

On December 1 of every year, the people of Iraq honor their war dead in what is known by decree of the Leader as Martyrs' Day. The focal point is the martyrs' monument, where the principal, official ceremony is held. At a quarter to ten on the morning of December 1, 1991--an unsuitable morning, sunny and blue and unseasonably, sweetly warm--a few hundred people were lined up in patient quietude before the heavy black steel security fence that guards the entrance. The fence is set on wheels in tracks, and opened and shut by electrical impulse. It was a professional crowd of mourners: soldiers, schoolchildren, government workers, and party hacks. Bureaucrats fussed around and through the crowd, herding everyone into just-so order. They were from the Ministry of Information and Culture, and they are known as "minders." As a foreigner, I had a minder assigned just to me, and he hovered at my shoulder like a hummingbird, nervous and eager to please.

In the vast and cruel hierarchy of the Iraqi state, minders are important enough to be disliked by their colleagues and charges, but not important enough to be respected or feared. The spies that matter, the sleek young louts of the Mukhabarat, have the power to torture and kill, and act like it. They wear sunglasses and black vinyl jackets and pleated Italian trousers, and swagger about Baghdad like Toonland gunsels. Minders wear the genteel-shabby suits of the clerking class. Formalized snitches, classroom monitors, they inspire only resentment and sneers behind their backs. They suffer from low self-esteem. In three trips to Iraq, I never learned their proper title. Everyone called them minders, and they even called themselves by this mildly deprecatory term: "Hello, I am your minder today," or "If you are going to go to the market, you must remember to take a minder."

At ten o'clock, the two long center sections of the fence jerked apart with a grinding, clanking rumble, and after a moment's hesitation the crowd moved forward, slowly, silently, up the walk to the big blue eggshells. At the front were the guests of honor, two war widows and an orphan. The widows were suitably dressed in black, but the child wore a bright pink party frock, puffed up with layers of frilly slips underneath.

Behind them came several platoons of boys dressed as soldiers, in crisp fatigues of blue or tan cloth stamped with a camouflage pattern. They wore gold epaulets on their narrow shoulders, and pink and white scarves around their skinny necks. They were no more than ten or eleven years old, and they were members of al-Talaia--the Vanguards--the state organization for citizens between the ages of ten and fifteen. Political indoctrination in Iraq actually begins when children enter school at the age of five or six, but al-Talaia is the first organized politico-military group to which one can belong. The young troops of the Vanguard learn to march and to follow orders, and to serve as junior agents of the state, filing reports on their peers and, on occasion, parents.

The little troopers marched up the walk as a unit, properly, with a childish semblance of military discipline, pumping their arms and swinging their legs in goose-stepping exuberance. Some carried bright paper parasols, which they twirled in ragged coordination. They chanted as they marched: "Long life to the Baath Party! Long life to Saddam Hussein!"

Behind the little Vanguard boys were similar platoons of little Vanguard girls, in blue uniform dresses, carrying flowers, walking along primly and properly, as if they might, by example, teach the boys how to behave. Trailing them was a sort of Toddlers' Auxiliary, children culled from various kindergartens and pre-kindergartens. There was one small boy I liked especially. He was tricked out in a miniature suit of black formal wear, with tails and a bow tie and a red sateen vest. He could not stay still; he danced all over the place.

At the base of the dome, where the gray granite gave way to white marble, the crowd coming in merged with the honor guard already in place. There were half a dozen units, all in parade dress, gaudy and grand and gleaming in the morning sun. The Republican Guards were the most glorious, in uniforms as fine as Victoria's own fusiliers, red tunics with blue sashes, and tall topees, with gold chin straps below and gold tassels stirring in the breeze above. They played drums and horns and clarinets, ushering in the mourners with a tune of a vaguely Sousa-ish nature. "It is a national song, very popular," my minder said. "It is called 'We Welcome the National War.'"

A couple of hundred feet of red carpet had been unrolled up the center of the approach to the pale little flame--almost invisible in the sunlight--in between the eggshells, and the assemblage gathered at the foot of this. Everyone was orderly. The only people making any noise were the musicians of the Republican Guard and the boys of al-Talaia, who had taken up the traditional song on these occasions.

"With our blood, with our souls, we sacrifice for Saddam," they trilled in their pretty, light boy-voices.

The ceremony did not take long. First, six middle-aged men in suits from the Arab Baath Socialist Party walked up and laid down a wreath in front of the small gas flame that burned from a hole set in a granite circle between the two halves of the dome. Then four middle-aged men in suits from the Iraqi National Student Union walked up and laid down a wreath. Then five men in suits and one woman in a suit from the Iraqi National Teachers' Union, etc.

As each delegation approached the end of the carpet, a brigadier general and two soldiers stepped in to escort them. The soldiers flanked the head of the delegation, who carried the wreath, and the three of them walked the last few steps to the flame with a properly slow, funereal gait. When the head of the delegation laid down the wreath, the soldiers did a little dance. Facing the monument, they brought their right legs up waist-high, and then stomped them down, made a half turn so they faced each other, and did it again, then executed a neat half circle to change sides, and a third high step-stomp. Facing front again, they did two rapid stomps, first with the left leg, then with the right; then an about face and a final stomp before the walk back down the carpet.

And on and on it went, all of a bleak, bleached sameness, each party trudging up, laying down its wreath as the honor guard jigged, trudging back: the General Secretariat of Iraqi Economic Advisers, the Iraqi Geologists' Union, the Iraqi Doctors' Union, the Union of Employees of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Iraqi Women's Federation, the Iraqi Friends of the Children Association, the General Federation of Arab Women, the Union of Employees of the Ministry of Information and Culture. As each group approached, the minder read its name off the wreath and whispered it in my ear. Once, he got excited. "Here is a group coming up that has no name on its wreath," he said. The oddity of this caused him to fall prey to a sudden false and wild hope. "Maybe it is just citizens." But then the breeze blew away a palm leaf that had been hiding a tag. "Oh," said the minder. "No. It is the Union of Employees of the Ministry of the Interior."

He seemed a little embarrassed, but the paucity of ordinary citizens was hardly his fault. Over the last quarter century, the Leader had killed off, one way or another, an astonishing number of the ordinary citizens of Iraq, and many of those left living in the winter of 1991 were too crippled or drunk or hungry to gin up much enthusiasm for the celebration of their condition.

Notă biografică

Michael Kelly