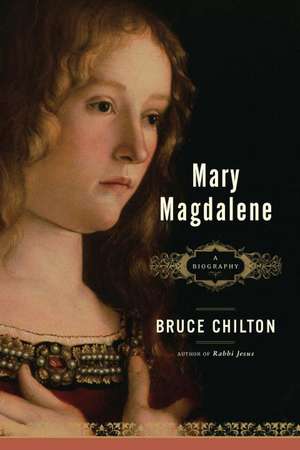

Mary Magdalene: A Biography

Autor Bruce Chiltonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 oct 2006

Chilton’s descriptions of who Mary Magdalene was and what she did challenge the male-dominated history of Christianity familiar to most readers. Placing Mary within the traditions of Jewish female savants, Chilton presents a visionary figure who was fully immersed in the mystical practices that shaped Jesus’ own teachings and a woman who was a religious master in her own right.

Preț: 88.66 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 133

Preț estimativ în valută:

16.97€ • 17.76$ • 14.12£

16.97€ • 17.76$ • 14.12£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780385513180

ISBN-10: 0385513186

Pagini: 220

Dimensiuni: 140 x 210 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.28 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: IMAGE

ISBN-10: 0385513186

Pagini: 220

Dimensiuni: 140 x 210 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.28 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: IMAGE

Notă biografică

Bruce Chilton is the Bernard Iddings Bell Professor of Religion at Bard College in Annandale–on–Hudson and priest at the Free Church of Saint John in Barrytown, New York. He is the author of many scholarly articles and books, including the widely acclaimed Rabbi Jesus and Rabbi Paul.

Extras

Chapter One

Possessed

* * *

And there were some women who had been healed from evil spirits and ailments--Mary who was called Magdalene, from whom seven demons had gone out, and Joanna, Khuza's wife (Herod's commissioner), and Susanna and many others who provided for them from their belongings.

Mary appears for the first time in the chronology of Jesus' life in this brief passage from Luke's Gospel (8:2-3). Luke indicates when she entered Jesus' life and why she sought him out. Jesus' reputation must have drawn her the ten hard miles from her home in Magdala to Capernaum, which is where he lived from 24 c.e. until the early part of 27 c.e. She probably came to him alone, on foot, over rock roads and rough paths, possessed by demons, her clothing in tatters. By my estimate, she sought him out in 25 c.e., after Jesus had become known in Galilee as a rabbi who opened his arms to people considered sinful and did battle with the demons that afflicted them. Jesus and Mary might conceivably have met when Jesus visited Magdala prior to 25 c.e., but there is no reference to that.

If she had begun her journey from Magdala with a woolen cloak--coveted by travelers for shelter at night as well as covering in rain and cold--that and any leather sandals she wore might well have been stolen. Cloaks and sandals, however, were not within reach of every family: The poor had to make their way barefoot, warmed only by the thick flax of their tunics. We can only imagine the toughness of these Galilean peasants, by day outdoors, even in the cold winter rains and occasional snow of the region.

Luke does not present Mary as the wealthy, elegant seductress of medieval legend and modern fantasy. In one vivid tale, frequently retold and embellished in the city of Ephesus in Asia Minor from the sixth century on, Mary was so wealthy that she was invited after Jesus' death to a dinner with Tiberius Caesar in Rome. She took the opportunity to preach of Jesus' Resurrection, only to be met with imperial derision. God would no more raise the dead, the emperor said, than he would turn the egg in Mary's hand from white to red. The egg immediately turned red. Orthodox Christians still recount this story at Easter, and Mary and her egg appear in the icons of Eastern Orthodoxy.

Some modern scholarship has attempted to buttress the picture of Mary's wealth by playing on her association with Joanna in Luke's Gospel, since Joanna had married into the prominent household of Herod Antipas, the ruler of Galilee. In one recent reconstruction, Mary and the influential Joanna were friends and colleagues in business; Mary exploited Joanna's contacts and used her own wealth to host dinner parties at which she employed Jesus as a comic. Revisionist readings, like medieval legends, can divert and refresh our imaginations, but they also show us how much the Western religious imagination still wants a rich and powerful Mary to protect the poor, defenseless Jesus.

But Luke's Gospel simply does not say Mary shared Joanna's status: It contrasts the two women. Among the women Luke mentions, Joanna, married to a government official, is aristocratic, perhaps wealthy, and well connected. Mary, on the other hand, doesn't have Joanna's status or connections. What she has are demons; no ancient text (nor any reasonable speculation) suggests that Jesus ever moved to Magdala or that Mary owned property there that she put at Jesus' disposal.

* * *

Luke does not indicate how old Mary was when she met Jesus, but she was most likely in her twenties, slightly older than he, mature enough to have developed a complicated case of possession (intimated by the reference to "seven demons"). The Gospels say nothing about her family. She was evidently unmarried at an age when one would expect a woman to have settled and produced children.

Given Mary's demonic possession, there is little mystery about her being single. Possession carried the stigma of impurity, not the natural impurity of childbirth (for example), but the contagion of an unclean spirit. She had no doubt been ostracized in Magdala in view of her many demons. The Jews of Galilee defined themselves, in contrast to the Gentiles around them, by their devotion to stringent laws of purity that were commanded by the Torah, the Law of Moses that was written in Hebrew and passed on in oral form in the Aramaic language. What they ate, whom they could eat and associate with, how they farmed, whom they could touch or not touch, the people they could marry, the kind of sex they had and when they had it--all this and more was determined by this Torah. The Galileans' purity was their identity, more precious and delightful in their minds than prosperity under the Romans or even survival. They resorted to violent resistance sporadically during the first century to expunge the impurity the Romans had brought to their land, even when that resistance proved suicidal.

"Unclean spirits," as Jesus and his followers often called demons, inhabited Mary. These demons were considered contagious, moving from person to person and place to place, transmitted by people like Mary who were known to be possessed. In the Hellenistic world, an invisible contagion of this kind was called a daimon, the origin of the word demon. But a daimon needn't be harmful in the sources of Greco-Roman thought. Daimones hovered in the space between the terrestrial world and the realm of the gods. When Socrates was asked how he knew how to act when he faced an ethical dilemma, he said that he listened to his daimonion ti, a nameless "little daimon" that guided him.

Judaism during this period referred to the same kind of forces, using the language of spirit and distinguishing between good spirits (such as angels and the Holy Spirit that God breathed over the world) and bad spirits. Jesus called harmful spiritual influences "unclean" or "evil" spirits, and the word daimon has been used in this sense within both Judaism and Christianity. After all, even a "good" daimon from the Hellenistic world was associated with idolatry, and that is why the term demon is used in a pejorative sense in modern languages influenced by Church practices.

Everyone in the ancient world, Jewish or not, agreed that daimonia could do harm, invading people, animals, and objects, inhabiting and possessing them. While daimonia are in some ways comparable to psychological complexes, they are also analogous to our bacteria, viruses, and microbes. People protected themselves from invisible daimonia with the care we devote to hygiene, and ancient experts listed them the way we catalog diseases and their alleged causes. Such lists have survived on fragments of papyrus that record the ancient craft of exorcism. The fact that these experts disagreed did not undermine belief in daimonia any more than changing health advice today makes people skeptical of science. Then, as now, conflict among experts only heightened belief in the vital importance of the subject.

Some scholars have argued that women in early Greece were thought more susceptible of possession than men, on the dubious grounds that their vaginas made their bodies vulnerable to entry. Ancient thought was usually subtler than that, and demons do not seem to have required many apertures or much room for maneuver. A person's eyes, ears, and nose were much more likely to expose him to their influences than any orifice below the waist.

* * *

However Mary came by her daimonia, they rendered her unclean within the society of Jewish Galilee. She was probably very much alone when she arrived in Capernaum.

In antiquity, women without families were vulnerable in ways that we can scarcely imagine. The Gospels typically identify a woman as a sister, wife, or mother of some man. That link was her protection. As happens in many cultures, a wife who was alone with any man but her husband in a private place became liable to the charge of adultery (Sotah 1:1-7 in the Mishnah, the tradition of Rabbinic teaching that put the Law of Moses into practice). Similarly, a man who stayed in his future father-in-law's house could not complain later that his wife was not a virgin, on the grounds that he might well have deflowered her, given half a chance. Women without men did not make themselves available; rather, men availed themselves of them.

From the custody of her father, a woman at puberty (around the age of thirteen) passed by marriage to the custody of a husband. Weddings were arranged between families that sought the advantage to both sides of increasing their families, the fields they farmed, the herds they tended, the labor force they could count on, and the contacts for trade that they could exploit. Marriage was a binding contract, sealed by a written record in literate communities, or by witnesses in illiterate peasant environments. A young woman remained in her father's home for a year or so after the marriage contract was agreed upon. Even with this delay of sexual relations, however, pregnant fourteen- and fifteen-year-old women must have been a relatively common sight.

This whole arrangement was designed to protect the purity of Israel's bloodlines by managing a woman's transition from puberty to childbearing with a husband who knew he had married a virgin. Taking another man's wife was therefore punishable by death in the Torah (Leviticus 20:10). Relations with a married woman constituted the sin of adultery, while seducing a virgin could be punished more lightly (Leviticus 22:16-17), sometimes only by a fine.

Unmarried women past the age of being virgins had a liminal, uncontrolled status, as troublesome to the families that had failed to marry them off as to the women themselves. Both men and women who had Israelite mothers but whose paternity was in doubt posed a particular problem when it came to marriage, because they could not marry most other Israelites. Like Jesus, Mary Magdalene might conceivably have been a mamzer, an Israelite whose paternity was doubtful and who was therefore restricted when it came to prospects for marriage.

Modern scholarship continues to parry the medieval tradition of portraying Mary as a prostitute at the time she encountered Jesus. But encouraging one's daughter to become a prostitute was prohibited, even if she was a financial burden. The punishment for promoting or allowing prostitution is not specified (Leviticus 19:29), and the fact is that prostitution did exist in and around Israel. But the practice was blamed for blighting the land. The whole concept behind the rules of purity was that Israel had been given a land to manage with attention and care so that it would continue to be fruitful. Sinful behavior produced impurity and pushed Israel toward annihilation: If Israelites stopped practicing the laws of purity, God threatened that the land itself would vomit them out (Leviticus 18:3-30).

Had Mary turned to prostitution before she met Jesus? Had she been raped or exploited during her journey from Magdala? Those are good questions, although no text or reasonable inference from a text answers them. To affirm or deny these possibilities takes us beyond the available evidence. But we can say that in Mary Magdalene's time and place--as in ours--likely victims of sin were often portrayed as being sinners themselves.

Luke's reference to Mary's seven demons encouraged the Western tradition that depicts her as a prostitute. Typical paintings portray her in lavish dress, arranging herself in front of a mirror, or abased in shame at Jesus' feet. Medieval piety associated vanity with prostitution, on the grounds that women sold themselves only because they enjoyed whoring, and pastoral theologians saw self-abasement, including flagellation on many occasions, as the best cure for this sin. Vanity and lust were kissing cousins within Mary's demonic menagerie prior to her exorcism, which was portrayed in the West as a conversion.

Mary Magdalene became popular as the patron saint of flagellants by the fourteenth century, and devotion to her and to the practice of self-inflicted pain was widespread. In one story of her life, she clawed at her skin until she bled, scored her breasts with stones, and tore out her hair, all as acts of penance for her self-indulgence. She long remained the ideal icon of mortification among the lay and clerical groups that encouraged similar penances. In 1375, an Italian fraternity of flagellants carried a banner during their processions as they whipped themselves; it depicts a giant enthroned Mary Magdalene. Her head reaches into the heavens and angels surround her. At her feet kneel four white-hooded figures, whose robes leave a gap at the back for ritual scourging.

Where did people in the medieval world find the material to produce such an image? Certainly not from the New Testament or from early traditions concerning Mary Magdalene. The woman whom the flagellants venerated was a combination of two different Marys: Mary Magdalene and Mary of Egypt. Mary of Egypt is herself a classic figure of Christian folklore, the whore turned ascetic. In stories that began to circulate during the sixth century, Mary of Egypt, for the sake of Christ, gave up her practice of prostitution during a pilgrimage to Jerusalem in the fourth century and lived in a cave for the rest of her life. This story was spliced into Mary Magdalene's biography.

According to this expanded tale, most famous in the thirteenth-century form in which it appears in The Golden Legend of Jacobus de Voragine, Mary traveled to France fourteen years after the Resurrection, founding churches and removing idols. In this lush legend, Mary Magdalene is confused with a completely different person in the Gospels, Mary of Bethany. This confusion provides her with a sister she never had (Martha of Bethany) as well as with a brother she never had (Lazarus). She could count on help in her missionary work from her brother Lazarus and her sister Martha, along with the aid of a boatload of Christians who had come with her and her siblings to Marseilles. Then she retreated for thirty anorexic years to an isolated cave in Provence, where she was fed miraculously during her times of prayer and meditation, when angels lifted her up to heaven.

The deep ambivalence about sexuality held by those within monastic culture did not, however, quite allow them to give up thinking about how desirable this former prostitute must have been after her conversion. She is often depicted as nude in the craggy rocks of La Sainte-Baume. Her long and lustrous hair, covering the parts of her body that modesty conventionally requires to be covered, is a staple of iconography in the West to this day, making Mary Magdalene the Lady Godiva of Christian spirituality.

From the Hardcover edition.

Possessed

* * *

And there were some women who had been healed from evil spirits and ailments--Mary who was called Magdalene, from whom seven demons had gone out, and Joanna, Khuza's wife (Herod's commissioner), and Susanna and many others who provided for them from their belongings.

Mary appears for the first time in the chronology of Jesus' life in this brief passage from Luke's Gospel (8:2-3). Luke indicates when she entered Jesus' life and why she sought him out. Jesus' reputation must have drawn her the ten hard miles from her home in Magdala to Capernaum, which is where he lived from 24 c.e. until the early part of 27 c.e. She probably came to him alone, on foot, over rock roads and rough paths, possessed by demons, her clothing in tatters. By my estimate, she sought him out in 25 c.e., after Jesus had become known in Galilee as a rabbi who opened his arms to people considered sinful and did battle with the demons that afflicted them. Jesus and Mary might conceivably have met when Jesus visited Magdala prior to 25 c.e., but there is no reference to that.

If she had begun her journey from Magdala with a woolen cloak--coveted by travelers for shelter at night as well as covering in rain and cold--that and any leather sandals she wore might well have been stolen. Cloaks and sandals, however, were not within reach of every family: The poor had to make their way barefoot, warmed only by the thick flax of their tunics. We can only imagine the toughness of these Galilean peasants, by day outdoors, even in the cold winter rains and occasional snow of the region.

Luke does not present Mary as the wealthy, elegant seductress of medieval legend and modern fantasy. In one vivid tale, frequently retold and embellished in the city of Ephesus in Asia Minor from the sixth century on, Mary was so wealthy that she was invited after Jesus' death to a dinner with Tiberius Caesar in Rome. She took the opportunity to preach of Jesus' Resurrection, only to be met with imperial derision. God would no more raise the dead, the emperor said, than he would turn the egg in Mary's hand from white to red. The egg immediately turned red. Orthodox Christians still recount this story at Easter, and Mary and her egg appear in the icons of Eastern Orthodoxy.

Some modern scholarship has attempted to buttress the picture of Mary's wealth by playing on her association with Joanna in Luke's Gospel, since Joanna had married into the prominent household of Herod Antipas, the ruler of Galilee. In one recent reconstruction, Mary and the influential Joanna were friends and colleagues in business; Mary exploited Joanna's contacts and used her own wealth to host dinner parties at which she employed Jesus as a comic. Revisionist readings, like medieval legends, can divert and refresh our imaginations, but they also show us how much the Western religious imagination still wants a rich and powerful Mary to protect the poor, defenseless Jesus.

But Luke's Gospel simply does not say Mary shared Joanna's status: It contrasts the two women. Among the women Luke mentions, Joanna, married to a government official, is aristocratic, perhaps wealthy, and well connected. Mary, on the other hand, doesn't have Joanna's status or connections. What she has are demons; no ancient text (nor any reasonable speculation) suggests that Jesus ever moved to Magdala or that Mary owned property there that she put at Jesus' disposal.

* * *

Luke does not indicate how old Mary was when she met Jesus, but she was most likely in her twenties, slightly older than he, mature enough to have developed a complicated case of possession (intimated by the reference to "seven demons"). The Gospels say nothing about her family. She was evidently unmarried at an age when one would expect a woman to have settled and produced children.

Given Mary's demonic possession, there is little mystery about her being single. Possession carried the stigma of impurity, not the natural impurity of childbirth (for example), but the contagion of an unclean spirit. She had no doubt been ostracized in Magdala in view of her many demons. The Jews of Galilee defined themselves, in contrast to the Gentiles around them, by their devotion to stringent laws of purity that were commanded by the Torah, the Law of Moses that was written in Hebrew and passed on in oral form in the Aramaic language. What they ate, whom they could eat and associate with, how they farmed, whom they could touch or not touch, the people they could marry, the kind of sex they had and when they had it--all this and more was determined by this Torah. The Galileans' purity was their identity, more precious and delightful in their minds than prosperity under the Romans or even survival. They resorted to violent resistance sporadically during the first century to expunge the impurity the Romans had brought to their land, even when that resistance proved suicidal.

"Unclean spirits," as Jesus and his followers often called demons, inhabited Mary. These demons were considered contagious, moving from person to person and place to place, transmitted by people like Mary who were known to be possessed. In the Hellenistic world, an invisible contagion of this kind was called a daimon, the origin of the word demon. But a daimon needn't be harmful in the sources of Greco-Roman thought. Daimones hovered in the space between the terrestrial world and the realm of the gods. When Socrates was asked how he knew how to act when he faced an ethical dilemma, he said that he listened to his daimonion ti, a nameless "little daimon" that guided him.

Judaism during this period referred to the same kind of forces, using the language of spirit and distinguishing between good spirits (such as angels and the Holy Spirit that God breathed over the world) and bad spirits. Jesus called harmful spiritual influences "unclean" or "evil" spirits, and the word daimon has been used in this sense within both Judaism and Christianity. After all, even a "good" daimon from the Hellenistic world was associated with idolatry, and that is why the term demon is used in a pejorative sense in modern languages influenced by Church practices.

Everyone in the ancient world, Jewish or not, agreed that daimonia could do harm, invading people, animals, and objects, inhabiting and possessing them. While daimonia are in some ways comparable to psychological complexes, they are also analogous to our bacteria, viruses, and microbes. People protected themselves from invisible daimonia with the care we devote to hygiene, and ancient experts listed them the way we catalog diseases and their alleged causes. Such lists have survived on fragments of papyrus that record the ancient craft of exorcism. The fact that these experts disagreed did not undermine belief in daimonia any more than changing health advice today makes people skeptical of science. Then, as now, conflict among experts only heightened belief in the vital importance of the subject.

Some scholars have argued that women in early Greece were thought more susceptible of possession than men, on the dubious grounds that their vaginas made their bodies vulnerable to entry. Ancient thought was usually subtler than that, and demons do not seem to have required many apertures or much room for maneuver. A person's eyes, ears, and nose were much more likely to expose him to their influences than any orifice below the waist.

* * *

However Mary came by her daimonia, they rendered her unclean within the society of Jewish Galilee. She was probably very much alone when she arrived in Capernaum.

In antiquity, women without families were vulnerable in ways that we can scarcely imagine. The Gospels typically identify a woman as a sister, wife, or mother of some man. That link was her protection. As happens in many cultures, a wife who was alone with any man but her husband in a private place became liable to the charge of adultery (Sotah 1:1-7 in the Mishnah, the tradition of Rabbinic teaching that put the Law of Moses into practice). Similarly, a man who stayed in his future father-in-law's house could not complain later that his wife was not a virgin, on the grounds that he might well have deflowered her, given half a chance. Women without men did not make themselves available; rather, men availed themselves of them.

From the custody of her father, a woman at puberty (around the age of thirteen) passed by marriage to the custody of a husband. Weddings were arranged between families that sought the advantage to both sides of increasing their families, the fields they farmed, the herds they tended, the labor force they could count on, and the contacts for trade that they could exploit. Marriage was a binding contract, sealed by a written record in literate communities, or by witnesses in illiterate peasant environments. A young woman remained in her father's home for a year or so after the marriage contract was agreed upon. Even with this delay of sexual relations, however, pregnant fourteen- and fifteen-year-old women must have been a relatively common sight.

This whole arrangement was designed to protect the purity of Israel's bloodlines by managing a woman's transition from puberty to childbearing with a husband who knew he had married a virgin. Taking another man's wife was therefore punishable by death in the Torah (Leviticus 20:10). Relations with a married woman constituted the sin of adultery, while seducing a virgin could be punished more lightly (Leviticus 22:16-17), sometimes only by a fine.

Unmarried women past the age of being virgins had a liminal, uncontrolled status, as troublesome to the families that had failed to marry them off as to the women themselves. Both men and women who had Israelite mothers but whose paternity was in doubt posed a particular problem when it came to marriage, because they could not marry most other Israelites. Like Jesus, Mary Magdalene might conceivably have been a mamzer, an Israelite whose paternity was doubtful and who was therefore restricted when it came to prospects for marriage.

Modern scholarship continues to parry the medieval tradition of portraying Mary as a prostitute at the time she encountered Jesus. But encouraging one's daughter to become a prostitute was prohibited, even if she was a financial burden. The punishment for promoting or allowing prostitution is not specified (Leviticus 19:29), and the fact is that prostitution did exist in and around Israel. But the practice was blamed for blighting the land. The whole concept behind the rules of purity was that Israel had been given a land to manage with attention and care so that it would continue to be fruitful. Sinful behavior produced impurity and pushed Israel toward annihilation: If Israelites stopped practicing the laws of purity, God threatened that the land itself would vomit them out (Leviticus 18:3-30).

Had Mary turned to prostitution before she met Jesus? Had she been raped or exploited during her journey from Magdala? Those are good questions, although no text or reasonable inference from a text answers them. To affirm or deny these possibilities takes us beyond the available evidence. But we can say that in Mary Magdalene's time and place--as in ours--likely victims of sin were often portrayed as being sinners themselves.

Luke's reference to Mary's seven demons encouraged the Western tradition that depicts her as a prostitute. Typical paintings portray her in lavish dress, arranging herself in front of a mirror, or abased in shame at Jesus' feet. Medieval piety associated vanity with prostitution, on the grounds that women sold themselves only because they enjoyed whoring, and pastoral theologians saw self-abasement, including flagellation on many occasions, as the best cure for this sin. Vanity and lust were kissing cousins within Mary's demonic menagerie prior to her exorcism, which was portrayed in the West as a conversion.

Mary Magdalene became popular as the patron saint of flagellants by the fourteenth century, and devotion to her and to the practice of self-inflicted pain was widespread. In one story of her life, she clawed at her skin until she bled, scored her breasts with stones, and tore out her hair, all as acts of penance for her self-indulgence. She long remained the ideal icon of mortification among the lay and clerical groups that encouraged similar penances. In 1375, an Italian fraternity of flagellants carried a banner during their processions as they whipped themselves; it depicts a giant enthroned Mary Magdalene. Her head reaches into the heavens and angels surround her. At her feet kneel four white-hooded figures, whose robes leave a gap at the back for ritual scourging.

Where did people in the medieval world find the material to produce such an image? Certainly not from the New Testament or from early traditions concerning Mary Magdalene. The woman whom the flagellants venerated was a combination of two different Marys: Mary Magdalene and Mary of Egypt. Mary of Egypt is herself a classic figure of Christian folklore, the whore turned ascetic. In stories that began to circulate during the sixth century, Mary of Egypt, for the sake of Christ, gave up her practice of prostitution during a pilgrimage to Jerusalem in the fourth century and lived in a cave for the rest of her life. This story was spliced into Mary Magdalene's biography.

According to this expanded tale, most famous in the thirteenth-century form in which it appears in The Golden Legend of Jacobus de Voragine, Mary traveled to France fourteen years after the Resurrection, founding churches and removing idols. In this lush legend, Mary Magdalene is confused with a completely different person in the Gospels, Mary of Bethany. This confusion provides her with a sister she never had (Martha of Bethany) as well as with a brother she never had (Lazarus). She could count on help in her missionary work from her brother Lazarus and her sister Martha, along with the aid of a boatload of Christians who had come with her and her siblings to Marseilles. Then she retreated for thirty anorexic years to an isolated cave in Provence, where she was fed miraculously during her times of prayer and meditation, when angels lifted her up to heaven.

The deep ambivalence about sexuality held by those within monastic culture did not, however, quite allow them to give up thinking about how desirable this former prostitute must have been after her conversion. She is often depicted as nude in the craggy rocks of La Sainte-Baume. Her long and lustrous hair, covering the parts of her body that modesty conventionally requires to be covered, is a staple of iconography in the West to this day, making Mary Magdalene the Lady Godiva of Christian spirituality.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

Praise for Rabbi Paul

“A worthwhile exploration of a life that has richly touched all of ours.” —Dallas Morning News

“[Chilton’s] inviting prose, ability to recreate the cultural contexts of Paul’s life, and deep affection for the Apostle bring new life to a tale that has been told many times before.” —Publishers Weekly

“An eloquent biographical masterpiece.” —Jerusalem Post

Praise for Rabbi Jesus

“Bruce Chilton’s masterpiece of religious narrative marks a genuinely new and important step beyond the now-faltering historical Jesus movement.” —Jacob Neusner, Jerusalem Post

“Open this book and see Jesus as you’ve never seen him . . . This is one heck of a good read.” —National Catholic Reporter

“Rabbi Jesus is a scholarly pursuit that reads more like a novel. The biography flows with the fluidity of an adventure tale, rich in characters, texture, and detail.” —The Herald-Sun (Durham, North Carolina)

From the Hardcover edition.

“A worthwhile exploration of a life that has richly touched all of ours.” —Dallas Morning News

“[Chilton’s] inviting prose, ability to recreate the cultural contexts of Paul’s life, and deep affection for the Apostle bring new life to a tale that has been told many times before.” —Publishers Weekly

“An eloquent biographical masterpiece.” —Jerusalem Post

Praise for Rabbi Jesus

“Bruce Chilton’s masterpiece of religious narrative marks a genuinely new and important step beyond the now-faltering historical Jesus movement.” —Jacob Neusner, Jerusalem Post

“Open this book and see Jesus as you’ve never seen him . . . This is one heck of a good read.” —National Catholic Reporter

“Rabbi Jesus is a scholarly pursuit that reads more like a novel. The biography flows with the fluidity of an adventure tale, rich in characters, texture, and detail.” —The Herald-Sun (Durham, North Carolina)

From the Hardcover edition.