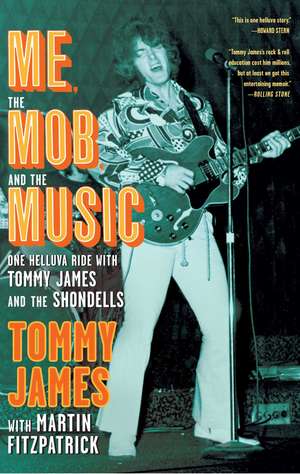

Me, the Mob, and the Music: One Helluva Ride with Tommy James & The Shondells

Autor Tommy James Cu Martin Fitzpatricken Limba Engleză Paperback – 13 apr 2011

In 1966, Tommy James' record 'Hanky Panky' was re-discovered by a Pittsburgh DJ who started playing it on heavy rotation, prompting a tremendous response. James found himself in the office of Morris Levy at Roulette Records, where he was handed a pen and ominously promised 'one helluva ride'. Morris Levy, the legendary 'godfather' of the music business, needed a hit and 'Hanky Panky' would be his. The song went to #1; James went on to record many more hits; and Levy continued to reign.

Me, the Mob, and the Musictells the intimate story of the complex and sometimes terrifying relationship between the bright-eyed, sweet-faced blonde musician from the heartland and the big, bombastic, brutal bully from the Bronx, who hustled, cheated, and swindled his way to the top of the music industry. It is also the story of this swaggering, wildly creative era of rock n' roll when the hits kept coming and payola and the strong arm tactics of the mob were the norm, and what it was like, for better or worse, to be in the middle of it.

Preț: 99.98 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 150

Preț estimativ în valută:

19.13€ • 19.90$ • 15.80£

19.13€ • 19.90$ • 15.80£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 25 martie-08 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781439172889

ISBN-10: 1439172889

Pagini: 240

Dimensiuni: 140 x 214 x 8 mm

Greutate: 0.22 kg

Editura: Scribner

Colecția Scribner

ISBN-10: 1439172889

Pagini: 240

Dimensiuni: 140 x 214 x 8 mm

Greutate: 0.22 kg

Editura: Scribner

Colecția Scribner

Notă biografică

Tommy James (born Thomas Gregory Jackson, April 29, 1947, Dayton, Ohio) is the pop-rock star best known as the leader of Tommy James and the Shondells. Performing locally in Niles, Michigan, from the age of 12, James went on to record many top hits, including "Hanky Panky," "I Think We're Alone Now," "Mony Mony," "Crimson and Clover," "Sweet Cherry Wine," "Mirage," "Do Something to Me," "Gettin’ Together," "Crystal Blue Persuasion," and "Draggin' the Line." He has sold over 100 million records, has been awarded twenty-three gold singles, and nine gold and platinum albums. His songs are widely used in television and film, and have been covered by Joan Jett, Billy Idol, Tiffany, Tom Jones, Prince, and R.E.M. Tommy James continues to tour the country and record.

Extras

PROLOGUE

May 21, 1990.

The day began with me rushing off to Chicago to do a concert promoting the release of my new album Hi-Fi and the single “Go.” It was my first studio album in nearly ten years. I was to meet Ron Alexenburg, the head of Aegis Records, and my manager, Carol Ross, at Newark Airport to catch a flight to Chicago. The band had already gone ahead, and we were all pretty excited about starting the nineties off with a new project. A host of radio stations and press were going to be there. Because Chicago had launched so many of our past successes, it seemed the perfect city to begin our tour. As my wife, Lynda, and I were about to leave, the phone suddenly rang. I was in a rush and kind of annoyed when I answered. It was my accountant, Howard Comart. In a very subdued voice he said, “Morris is asking for you. If you want to see him you’d better get up here right away.”

“Oh my God, Howard, I’m dashing out the door to do a show in Chicago. I’ll be back first thing tomorrow morning and I’ll come right up.” There was a pause. Howard said, “Well, okay.” But there was a tremor in his voice. I gave him my hotel number in Chicago and told him to keep me posted.

When I got to the airport, I told Ron and Carol the situation, and it cast a shadow over our otherwise joyful morning. The Godfather of the music business, Morris Levy, was dying of cancer. We all had a feeling of disbelief because none of us had ever thought of Morris as anything but invincible. In his sixty-two years, he had created and controlled one of the biggest independent music publishing companies; managed and was partners with the most famous rock and roll disc jockey, Alan Freed; owned the most famous jazz club in history, Birdland; and owned one of the most successful independent record labels of the fifties and sixties, Roulette Records, which also was my record label for eight years.

Morris and I had been exchanging messages through Howard, our mutual accountant, for several weeks, almost like two kids passing notes back and forth in school. I knew he understood how saddened I was by the whole thing and that despite everything, I genuinely cared about him.

When we got off the plane at O’Hare, I was suddenly filled with the old excitement; a sold-out show, in Chicago, to promote a new record. It felt good to feel this again twenty-four years after first signing with Morris and Roulette. Our road manager met us at baggage claim, a limo was waiting outside, and we loaded up and headed for the hotel. The rest of the day went pretty smoothly, the sound check and all the backstage stuff. But all I kept thinking about was Morris. Lynda kept checking our messages at the hotel hourly.

The show went great; the audience went crazy, dancing in the aisles, standing on their seats screaming for more. We played a combination of the hits and the new stuff, but even on stage I was preoccupied. We ended the show with “Mony Mony,” like we had done ten thousand times, and did the usual encore. Like always I was hot, sweaty, and out of breath when I came off stage. Carol and Ron met me by the stage door and we all walked back to the dressing room. I had an interview to do with a young radio guy from a local pop station. There was a lot of whooping and hollering around me as I sat down to catch my breath in front of the dressing room mirror. The DJ started asking me questions and I could see the cassette player rolling. The interview had begun. I started off with how great it was to be back in Chicago, then Lynda suddenly came into the room holding a piece of paper. She said, “I’m sorry to interrupt, Tommy, but Morris Levy died.”

There was just silence. All day long I had been thinking about what I was going to say to him, and now I’d never get the chance. I’d heard stories of how emaciated he had become and had imagined what I would feel seeing him like that, but it didn’t matter now because I would never see him again.

At that point my interviewer said, “Excuse me, Tommy, can I ask you a question?” I nodded and he said, “Who is Morris Levy?”

Wow, who is Morris Levy? I looked at him in astonishment and realized this kid couldn’t be more than twenty-one or twenty-two years old.

“How much time do we have?”

“As much time as you want. I came for an in-depth interview.”

“Well, you’re going to get one. Is that tape recorder still running?”

© 2010 Tommy James

May 21, 1990.

The day began with me rushing off to Chicago to do a concert promoting the release of my new album Hi-Fi and the single “Go.” It was my first studio album in nearly ten years. I was to meet Ron Alexenburg, the head of Aegis Records, and my manager, Carol Ross, at Newark Airport to catch a flight to Chicago. The band had already gone ahead, and we were all pretty excited about starting the nineties off with a new project. A host of radio stations and press were going to be there. Because Chicago had launched so many of our past successes, it seemed the perfect city to begin our tour. As my wife, Lynda, and I were about to leave, the phone suddenly rang. I was in a rush and kind of annoyed when I answered. It was my accountant, Howard Comart. In a very subdued voice he said, “Morris is asking for you. If you want to see him you’d better get up here right away.”

“Oh my God, Howard, I’m dashing out the door to do a show in Chicago. I’ll be back first thing tomorrow morning and I’ll come right up.” There was a pause. Howard said, “Well, okay.” But there was a tremor in his voice. I gave him my hotel number in Chicago and told him to keep me posted.

When I got to the airport, I told Ron and Carol the situation, and it cast a shadow over our otherwise joyful morning. The Godfather of the music business, Morris Levy, was dying of cancer. We all had a feeling of disbelief because none of us had ever thought of Morris as anything but invincible. In his sixty-two years, he had created and controlled one of the biggest independent music publishing companies; managed and was partners with the most famous rock and roll disc jockey, Alan Freed; owned the most famous jazz club in history, Birdland; and owned one of the most successful independent record labels of the fifties and sixties, Roulette Records, which also was my record label for eight years.

Morris and I had been exchanging messages through Howard, our mutual accountant, for several weeks, almost like two kids passing notes back and forth in school. I knew he understood how saddened I was by the whole thing and that despite everything, I genuinely cared about him.

When we got off the plane at O’Hare, I was suddenly filled with the old excitement; a sold-out show, in Chicago, to promote a new record. It felt good to feel this again twenty-four years after first signing with Morris and Roulette. Our road manager met us at baggage claim, a limo was waiting outside, and we loaded up and headed for the hotel. The rest of the day went pretty smoothly, the sound check and all the backstage stuff. But all I kept thinking about was Morris. Lynda kept checking our messages at the hotel hourly.

The show went great; the audience went crazy, dancing in the aisles, standing on their seats screaming for more. We played a combination of the hits and the new stuff, but even on stage I was preoccupied. We ended the show with “Mony Mony,” like we had done ten thousand times, and did the usual encore. Like always I was hot, sweaty, and out of breath when I came off stage. Carol and Ron met me by the stage door and we all walked back to the dressing room. I had an interview to do with a young radio guy from a local pop station. There was a lot of whooping and hollering around me as I sat down to catch my breath in front of the dressing room mirror. The DJ started asking me questions and I could see the cassette player rolling. The interview had begun. I started off with how great it was to be back in Chicago, then Lynda suddenly came into the room holding a piece of paper. She said, “I’m sorry to interrupt, Tommy, but Morris Levy died.”

There was just silence. All day long I had been thinking about what I was going to say to him, and now I’d never get the chance. I’d heard stories of how emaciated he had become and had imagined what I would feel seeing him like that, but it didn’t matter now because I would never see him again.

At that point my interviewer said, “Excuse me, Tommy, can I ask you a question?” I nodded and he said, “Who is Morris Levy?”

Wow, who is Morris Levy? I looked at him in astonishment and realized this kid couldn’t be more than twenty-one or twenty-two years old.

“How much time do we have?”

“As much time as you want. I came for an in-depth interview.”

“Well, you’re going to get one. Is that tape recorder still running?”

© 2010 Tommy James

Recenzii

"Tommy James's story is one of the most interesting of any of the 1960s rockers. . . . His story reads like a music-industry version of 'Goodfellas.'"--Denver Post

“A boisterous memoir . . . It’s high time that [Tommy James] had a book to himself.”

—Janet Maslin, The New York Times

"Tommy James' rock & roll education cost him millions, but at least we got this entertaining memoir."--Rolling Stone

"This is one helluva story."--Howard Stern

“A boisterous memoir . . . It’s high time that [Tommy James] had a book to himself.”

—Janet Maslin, The New York Times

"Tommy James' rock & roll education cost him millions, but at least we got this entertaining memoir."--Rolling Stone

"This is one helluva story."--Howard Stern

Descriere

Tommy James’s wild and entertaining true story of his career—part rock & roll fairytale, part mob epic—that “reads like a music-industry version of Goodfellas” (The Denver Post).