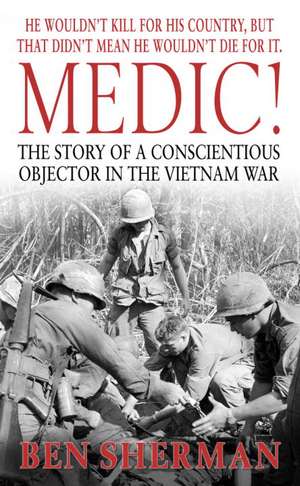

Medic!: The Story of a Conscientious Objector in the Vietnam War

Autor Ben Shermanen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mai 2004

Preț: 47.25 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 71

Preț estimativ în valută:

9.04€ • 9.44$ • 7.48£

9.04€ • 9.44$ • 7.48£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 15-29 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780891418481

ISBN-10: 0891418482

Pagini: 304

Dimensiuni: 110 x 178 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.15 kg

Ediția:Mass Market.

Editura: Presidio Press

Locul publicării:United States

ISBN-10: 0891418482

Pagini: 304

Dimensiuni: 110 x 178 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.15 kg

Ediția:Mass Market.

Editura: Presidio Press

Locul publicării:United States

Extras

1

Bags

The bags are exactly where I should begin. They are where the war ended for fifty-eight thousand, and where it started for me. Black rubberized bags with reinforced plastic handles on each end, they were strong and durable, with heavy zippers you could pull with your whole fist.

Entering the morgue tent, one hesitated to take a full breath. My first duty in Vietnam was spent zipping up smells. The only solace was that the remains had quit screaming. Some bodies had the distinct odor of burnt cloth or flesh. Others simply gave off old sweat, bad socks, tobacco, or belly gas. Even a tent vaporized with Lysol couldn't cut the continuous olfactory blight of human waste staining the underwear of the shell left behind.

Our caring was meticulous, even while we tried, in our own way, to put our minds elsewhere. Each personal item was tagged, each button refastened. Neglected pockets and stripes were neatly resewn. Homely, wondering faces were shaved and cleaned. Without a sound, we each functioned with one mind, one obligation. Someone inventoried each coin, chain, watch, wallet, ring, and all were placed in small brown paper sacks. No one wanted their loved one coming home with someone else's personal stuff in his pocket or with field dirt ringing his neck. And the army didn't want a hometown mortician opening the box to find a mess instead of a hero.

For every face locked into every rubber womb, I made a quiet promise to do this or that with my life for his sake. With some pride, I thought that as a medic I stood for part of the solution. I had come to this place to save a life, not take one. This plugging of rectums with cotton balls was a temporary setback. In one year minus one day, I could scrutinize my life for whatever meaning this horror held. A year from now I might even laugh out loud again.

"Graves Registration?" I asked the clerk. "But I'm a medic."

"New medics get the morgue tent first. Anything's better than the bush. Nobody asks for the morgue. But it'll pop your cherry. You'll be ready for anything after a few days of body-packing."

"Uh, I don't . . ."

"I know. The guys over there'll show you what to do. They're not grave diggers, either. Plain old medics like you."

"We dig graves here?"

"Nope. 'Grave diggers' are what we call the regular morgue specialists, lifers in Saigon at the big hospitals."

"Uh-huh." I scrambled to keep up. His words and feet were way ahead of me, heading down the dirt road.

"We don't get that many DOA anyway. It'll be pretty boring here. Just passing a few days, y'know? Only bodies we get are those who died in flight or across the street at 3d Surg. Most field KIAs go straight to Saigon. Then home."

KIA. Killed in action.

Upon entering the tent, the clerk handed me a blue tunic to exchange for my fatigue shirt, then disappeared without another word. Two lanky black medics worked over a corpse on a stainless steel table. They nodded politely but didn't speak. Their mouths puffed forward in a pout, like you had to hold your lips a certain way to concentrate. Their eyes were swollen, and I rubbed my own as the stench of disinfectant mixed with the humidity in the tent. I hung my fatigue shirt on a hook by the door next to their two. The stenciled names weren't showing. I didn't introduce myself, and they didn't offer.

The two of them taught me by show rather than tell. When they were done preparing the corpse, I helped roll him onto an open rubber bag. One of them placed the brown paper sack full of personal belongings carefully between the knees as the other zipped the bag from the feet up over the head. A chill rocketed from my toes to my neck at the sound. The two of them picked up the full heavy bag by the two side handles and slid it into a silver aluminum box, then closed the cover and snapped it shut.

The gurney bumped over the back threshold of the tent as they rolled the box out to be stored in a refrigerated steel building behind the morgue. Somebody else would ship him home.

Stacked at the end of the morgue tent were more six-foot-long aluminum boxes. Ten or twelve of them. Each one eventually took somebody home. Near the stack of caskets, an open shelf stored extra sets of large fatigue pants and shirts and piles of olive drab T-shirts and socks. An open bandage box held dozens of packs of varying brands and quantities of cigarettes.

I helped with the next KIA, who was about five years younger than I. This one's fatigues were wet and bloody, so we cut the clothes off. We carefully washed his arms, face, feet, even behind his ears and between his fingers. Then we dressed him carefully in new starched fatigues from the shelves in the corner. We all scrubbed our hands thoroughly afterward.

On the second day we packed three more bodies, all dank with the musk of too many days in rice paddies. You couldn't inhale in our tent without the sharp medical scent of liquid soap and alcohol cutting through the stench of death. One of the medics showed me how he stuffed unused cigarette filters into his nostrils. It didn't work. The disgusting odor cut through everything.

The morgue tent could have been called Purgatory. The casualties weren't part of the fighting force anymore, but they hadn't yet touched down in their hometowns, where friends, family, and high school teachers would be there to greet them for the final time. Where they'd soon be war heroes.

Until then, inside this tent, the three of us took our time and paid attention to detail. These bodies were important. They were different from us only in that they were going home early.

In bags. Once closed, you couldn't see the bewildered faces anymore. You couldn't smell the blood, excrement, dried mud, or urine. Each one we zipped meant everyone had quit messing with him. No snipers or booby traps or command-detonated mines to slow his walk. No weight of cumbersome gear, weapons, and ammunition. No whistling rockets or mortars in his ears just before they hit. No sudden flinching or jerking. No fear. What a way to leave.

Repeatedly before me, on a cold stainless steel table, lay the one common denominator of escalated conflict: dead bodies. No matter what provokes nations to war upon each other--land, oil, trade, religion--this bagging of boys is as fundamental to war as haiku is to poetry.

High speeding metal

Slamming through muscle and bone

How war begins, ends

I scribbled the words on the back of a red toe tag. I didn't know it yet, but the tranquility of this Purgatory was far better than the screaming that preceded it, the hysteria I would catch up with soon enough in the field. For now, our shop remained eternally mute.

As soldiers, we were all isolated from the World. None of us saw the nightly news or read the newspapers. We didn't know enough to care one way or the other. GIs are not allowed opinions. Basic training whips the smartass out of every individual, one at a time, and creates a government-issue fighting soldier who doesn't have too many original thoughts. Real warriors are either alive and afraid, or dead and quiet. In the field there were no lines, no battles, no war strategies. Guerrilla warfare is nowhere and everywhere at the same time. My recollection of Vietnam has nothing to do with politics or Americans shouting in the streets back home. It's about serving in a humid foreign jungle, flicking horsefly mosquitoes, eating crappy food, trying to find a bit of shade or a beer or a soft breeze to slice into the humidity that hung on our necks. And about trying to stay alive.

My official papers said I was a noncombatant, which meant that I didn't carry a weapon. It didn't mean I wasn't going to get shot at, it just meant I didn't carry a weapon. But being a medic meant much more than carrying a weapon. It meant ten weeks of bloody movies, hypodermic needle drills, greased catheters slipped into wilting penises, splints made of tree limbs, fireman body-carries through mud, machine gun tracers colliding over crawling bodies, a morphine Syrette administered to a bare thigh in front of the whole gawking platoon.

Medics carried responsibility for more than dry feet, salt tablets, syphilis, and puncture wounds. A platoon leader relied on his medic to report on the morale and mobility of the troops. A medevac pilot relied on the medics to get out into the battlefield and back quickly. Operating room surgeons who had years of study and more years of practice relied on "ten-week wonders" like me to scrub, monitor vitals, sponge, pass instruments, administer anesthetics, even carve out and sew up wounds.

The grunts called me Doc, and it sounded like both Mom and Priest.

Medics were trusted to perform when needed. We treated abrasions, gave haircuts, soothed anger, and inspected rashes of unknown origin in all the typical places. We also confiscated marijuana; treated cuts, bug bites, and abrasions; and continually nagged people to keep their feet clean and their dicks to themselves. Yet no matter how much a medic bitched, he held your ticket home alive--if he knew his stuff. For that reason, I belonged to a proud fraternity.

I wondered if all new medics caught morgue duty as a way to desensitize us. You couldn't have one of us puking into an open wound. The clerk had said "temporary" duty. To some extent the whole war seemed like a fleeting mishap in my otherwise normal life. "Temporary" would have to be my mantra.

Working in the morgue tent may have been gruesome and smelly, but it kept us feeling reasonably safe. The hundred-degree heat started early, stayed through the afternoon, and hung on late into the evening. Inside the tent seemed even hotter than outside. If a monsoon dumped rain on us for fifteen minutes, the temperature might drop five degrees. Minutes later it climbed back up to over a hundred, with ninety-nine percent humidity. It seemed that even if the bullets and rockets missed, the weather would probably kill me.

I slept intermittently the first night after morgue duty. I awoke twice to sirens warning of incoming rockets. Half awake, I'd scramble into the bunkers. It felt much more like a nuisance than real safety. After a day of dead bodies, one can only experience a heightened level of fear for so long, then the nerves just go numb. The second night I remained in the morgue, passing time straightening clothes and supplies. When the sirens blasted again, at least I didn't have to wake up. And I was certainly in the right place if I bought the farm. Weary and bored, I wrote a note and took it out to the refrigerated building. I opened the last casket we'd prepared and dropped it in with the bagged body.

The third day I wrote something special and added it to three of the bags. The first two notes were simply "Smooth sailing" and "Good luck on the other side." But in the late morning I got inspired and wrote a full letter. I imagined the Stateside mortician opening the bag, reading it, and passing it on to the family. I asked if they had thought about this guy much before he died, and if they had thought about anything else since. I wrote about who and where I was, and that I wanted to know about the fellow whose body I had tended. I asked them to write and tell me about him.

I didn't get any replies. Didn't really expect any. I had dared to cross the line into somebody's grief without invitation. What could they write back anyway? But I had to do something to make the bodies real for me. Otherwise, we were stuffing limp meat into containers.

The bodies came sporadically. As we zipped away somebody's son, I thought that this one couldn't have been more than seventeen, at least five years younger than the guy wrapping him in a bag. He had perfect teeth. Must have had braces. I wondered what that had cost his folks. Looking down, I saw that what had been his last meal now stained my forearms.

I scoured my hands and arms clear up to the shoulders, standing at the sink long enough to hide my tears from the others. One of the two medics approached and put his hand on my back. I turned to look at him, trying to bite back my feelings.

"I'm Vincent," he said. "That there is Satterfield."

2

Papers

Selective Service System

CLASSIFICATION

Local Board No. 23

September 24, 1964

TO: Benjamin Ray Sherman,

Selective Service No. 4 23 46 321

1. By authority of the Selective Service Regulations 100.4, you are hereby classified 2-S [student deferment].

2. This classification will terminate if at any time the reasons thereof cease to exist. It is your duty to report that fact immediately to this local board.

3. It is your continuous duty to report for induction at such time and place as may hereafter be fixed by this local board.

October 10, 1964

Dear Ben,

I truly look forward to our meeting. I haven't seen you since you were but a lad of four or five, quite active I recall. Your dear mother seemed to be the only authority you heeded. This is a good choice, by the way.

In preparation for our visit next week, I have jotted some notes for your consideration.

1. First, your question about not complying: Conviction for a draft law violation typically means up to five years' imprisonment at a federal penitentiary and a fine of up to $10,000.

2. You may apply for Conscientious Objector [CO] status by filling out a Form 150 (enclosed) and sending it to your Selective Service Board.

3. By reading, you can see that you are required to write an essay about your reasons, the religious nature of your beliefs, the development of those beliefs since early childhood, and any public or private expressions of your pacifism. You may also be required to appear in person before your board to answer their questions about what you have submitted.

4. 1-O status means alternative service. You state that you are not willing to serve the military in any fashion. That matches my status in WWII. I served five years in a CO internment camp, not much unlike a prison. Nowadays, this classification is almost impossible to receive unless you are a member of the Quaker church, or one similar, or you are the son of a minister.

Bags

The bags are exactly where I should begin. They are where the war ended for fifty-eight thousand, and where it started for me. Black rubberized bags with reinforced plastic handles on each end, they were strong and durable, with heavy zippers you could pull with your whole fist.

Entering the morgue tent, one hesitated to take a full breath. My first duty in Vietnam was spent zipping up smells. The only solace was that the remains had quit screaming. Some bodies had the distinct odor of burnt cloth or flesh. Others simply gave off old sweat, bad socks, tobacco, or belly gas. Even a tent vaporized with Lysol couldn't cut the continuous olfactory blight of human waste staining the underwear of the shell left behind.

Our caring was meticulous, even while we tried, in our own way, to put our minds elsewhere. Each personal item was tagged, each button refastened. Neglected pockets and stripes were neatly resewn. Homely, wondering faces were shaved and cleaned. Without a sound, we each functioned with one mind, one obligation. Someone inventoried each coin, chain, watch, wallet, ring, and all were placed in small brown paper sacks. No one wanted their loved one coming home with someone else's personal stuff in his pocket or with field dirt ringing his neck. And the army didn't want a hometown mortician opening the box to find a mess instead of a hero.

For every face locked into every rubber womb, I made a quiet promise to do this or that with my life for his sake. With some pride, I thought that as a medic I stood for part of the solution. I had come to this place to save a life, not take one. This plugging of rectums with cotton balls was a temporary setback. In one year minus one day, I could scrutinize my life for whatever meaning this horror held. A year from now I might even laugh out loud again.

"Graves Registration?" I asked the clerk. "But I'm a medic."

"New medics get the morgue tent first. Anything's better than the bush. Nobody asks for the morgue. But it'll pop your cherry. You'll be ready for anything after a few days of body-packing."

"Uh, I don't . . ."

"I know. The guys over there'll show you what to do. They're not grave diggers, either. Plain old medics like you."

"We dig graves here?"

"Nope. 'Grave diggers' are what we call the regular morgue specialists, lifers in Saigon at the big hospitals."

"Uh-huh." I scrambled to keep up. His words and feet were way ahead of me, heading down the dirt road.

"We don't get that many DOA anyway. It'll be pretty boring here. Just passing a few days, y'know? Only bodies we get are those who died in flight or across the street at 3d Surg. Most field KIAs go straight to Saigon. Then home."

KIA. Killed in action.

Upon entering the tent, the clerk handed me a blue tunic to exchange for my fatigue shirt, then disappeared without another word. Two lanky black medics worked over a corpse on a stainless steel table. They nodded politely but didn't speak. Their mouths puffed forward in a pout, like you had to hold your lips a certain way to concentrate. Their eyes were swollen, and I rubbed my own as the stench of disinfectant mixed with the humidity in the tent. I hung my fatigue shirt on a hook by the door next to their two. The stenciled names weren't showing. I didn't introduce myself, and they didn't offer.

The two of them taught me by show rather than tell. When they were done preparing the corpse, I helped roll him onto an open rubber bag. One of them placed the brown paper sack full of personal belongings carefully between the knees as the other zipped the bag from the feet up over the head. A chill rocketed from my toes to my neck at the sound. The two of them picked up the full heavy bag by the two side handles and slid it into a silver aluminum box, then closed the cover and snapped it shut.

The gurney bumped over the back threshold of the tent as they rolled the box out to be stored in a refrigerated steel building behind the morgue. Somebody else would ship him home.

Stacked at the end of the morgue tent were more six-foot-long aluminum boxes. Ten or twelve of them. Each one eventually took somebody home. Near the stack of caskets, an open shelf stored extra sets of large fatigue pants and shirts and piles of olive drab T-shirts and socks. An open bandage box held dozens of packs of varying brands and quantities of cigarettes.

I helped with the next KIA, who was about five years younger than I. This one's fatigues were wet and bloody, so we cut the clothes off. We carefully washed his arms, face, feet, even behind his ears and between his fingers. Then we dressed him carefully in new starched fatigues from the shelves in the corner. We all scrubbed our hands thoroughly afterward.

On the second day we packed three more bodies, all dank with the musk of too many days in rice paddies. You couldn't inhale in our tent without the sharp medical scent of liquid soap and alcohol cutting through the stench of death. One of the medics showed me how he stuffed unused cigarette filters into his nostrils. It didn't work. The disgusting odor cut through everything.

The morgue tent could have been called Purgatory. The casualties weren't part of the fighting force anymore, but they hadn't yet touched down in their hometowns, where friends, family, and high school teachers would be there to greet them for the final time. Where they'd soon be war heroes.

Until then, inside this tent, the three of us took our time and paid attention to detail. These bodies were important. They were different from us only in that they were going home early.

In bags. Once closed, you couldn't see the bewildered faces anymore. You couldn't smell the blood, excrement, dried mud, or urine. Each one we zipped meant everyone had quit messing with him. No snipers or booby traps or command-detonated mines to slow his walk. No weight of cumbersome gear, weapons, and ammunition. No whistling rockets or mortars in his ears just before they hit. No sudden flinching or jerking. No fear. What a way to leave.

Repeatedly before me, on a cold stainless steel table, lay the one common denominator of escalated conflict: dead bodies. No matter what provokes nations to war upon each other--land, oil, trade, religion--this bagging of boys is as fundamental to war as haiku is to poetry.

High speeding metal

Slamming through muscle and bone

How war begins, ends

I scribbled the words on the back of a red toe tag. I didn't know it yet, but the tranquility of this Purgatory was far better than the screaming that preceded it, the hysteria I would catch up with soon enough in the field. For now, our shop remained eternally mute.

As soldiers, we were all isolated from the World. None of us saw the nightly news or read the newspapers. We didn't know enough to care one way or the other. GIs are not allowed opinions. Basic training whips the smartass out of every individual, one at a time, and creates a government-issue fighting soldier who doesn't have too many original thoughts. Real warriors are either alive and afraid, or dead and quiet. In the field there were no lines, no battles, no war strategies. Guerrilla warfare is nowhere and everywhere at the same time. My recollection of Vietnam has nothing to do with politics or Americans shouting in the streets back home. It's about serving in a humid foreign jungle, flicking horsefly mosquitoes, eating crappy food, trying to find a bit of shade or a beer or a soft breeze to slice into the humidity that hung on our necks. And about trying to stay alive.

My official papers said I was a noncombatant, which meant that I didn't carry a weapon. It didn't mean I wasn't going to get shot at, it just meant I didn't carry a weapon. But being a medic meant much more than carrying a weapon. It meant ten weeks of bloody movies, hypodermic needle drills, greased catheters slipped into wilting penises, splints made of tree limbs, fireman body-carries through mud, machine gun tracers colliding over crawling bodies, a morphine Syrette administered to a bare thigh in front of the whole gawking platoon.

Medics carried responsibility for more than dry feet, salt tablets, syphilis, and puncture wounds. A platoon leader relied on his medic to report on the morale and mobility of the troops. A medevac pilot relied on the medics to get out into the battlefield and back quickly. Operating room surgeons who had years of study and more years of practice relied on "ten-week wonders" like me to scrub, monitor vitals, sponge, pass instruments, administer anesthetics, even carve out and sew up wounds.

The grunts called me Doc, and it sounded like both Mom and Priest.

Medics were trusted to perform when needed. We treated abrasions, gave haircuts, soothed anger, and inspected rashes of unknown origin in all the typical places. We also confiscated marijuana; treated cuts, bug bites, and abrasions; and continually nagged people to keep their feet clean and their dicks to themselves. Yet no matter how much a medic bitched, he held your ticket home alive--if he knew his stuff. For that reason, I belonged to a proud fraternity.

I wondered if all new medics caught morgue duty as a way to desensitize us. You couldn't have one of us puking into an open wound. The clerk had said "temporary" duty. To some extent the whole war seemed like a fleeting mishap in my otherwise normal life. "Temporary" would have to be my mantra.

Working in the morgue tent may have been gruesome and smelly, but it kept us feeling reasonably safe. The hundred-degree heat started early, stayed through the afternoon, and hung on late into the evening. Inside the tent seemed even hotter than outside. If a monsoon dumped rain on us for fifteen minutes, the temperature might drop five degrees. Minutes later it climbed back up to over a hundred, with ninety-nine percent humidity. It seemed that even if the bullets and rockets missed, the weather would probably kill me.

I slept intermittently the first night after morgue duty. I awoke twice to sirens warning of incoming rockets. Half awake, I'd scramble into the bunkers. It felt much more like a nuisance than real safety. After a day of dead bodies, one can only experience a heightened level of fear for so long, then the nerves just go numb. The second night I remained in the morgue, passing time straightening clothes and supplies. When the sirens blasted again, at least I didn't have to wake up. And I was certainly in the right place if I bought the farm. Weary and bored, I wrote a note and took it out to the refrigerated building. I opened the last casket we'd prepared and dropped it in with the bagged body.

The third day I wrote something special and added it to three of the bags. The first two notes were simply "Smooth sailing" and "Good luck on the other side." But in the late morning I got inspired and wrote a full letter. I imagined the Stateside mortician opening the bag, reading it, and passing it on to the family. I asked if they had thought about this guy much before he died, and if they had thought about anything else since. I wrote about who and where I was, and that I wanted to know about the fellow whose body I had tended. I asked them to write and tell me about him.

I didn't get any replies. Didn't really expect any. I had dared to cross the line into somebody's grief without invitation. What could they write back anyway? But I had to do something to make the bodies real for me. Otherwise, we were stuffing limp meat into containers.

The bodies came sporadically. As we zipped away somebody's son, I thought that this one couldn't have been more than seventeen, at least five years younger than the guy wrapping him in a bag. He had perfect teeth. Must have had braces. I wondered what that had cost his folks. Looking down, I saw that what had been his last meal now stained my forearms.

I scoured my hands and arms clear up to the shoulders, standing at the sink long enough to hide my tears from the others. One of the two medics approached and put his hand on my back. I turned to look at him, trying to bite back my feelings.

"I'm Vincent," he said. "That there is Satterfield."

2

Papers

Selective Service System

CLASSIFICATION

Local Board No. 23

September 24, 1964

TO: Benjamin Ray Sherman,

Selective Service No. 4 23 46 321

1. By authority of the Selective Service Regulations 100.4, you are hereby classified 2-S [student deferment].

2. This classification will terminate if at any time the reasons thereof cease to exist. It is your duty to report that fact immediately to this local board.

3. It is your continuous duty to report for induction at such time and place as may hereafter be fixed by this local board.

October 10, 1964

Dear Ben,

I truly look forward to our meeting. I haven't seen you since you were but a lad of four or five, quite active I recall. Your dear mother seemed to be the only authority you heeded. This is a good choice, by the way.

In preparation for our visit next week, I have jotted some notes for your consideration.

1. First, your question about not complying: Conviction for a draft law violation typically means up to five years' imprisonment at a federal penitentiary and a fine of up to $10,000.

2. You may apply for Conscientious Objector [CO] status by filling out a Form 150 (enclosed) and sending it to your Selective Service Board.

3. By reading, you can see that you are required to write an essay about your reasons, the religious nature of your beliefs, the development of those beliefs since early childhood, and any public or private expressions of your pacifism. You may also be required to appear in person before your board to answer their questions about what you have submitted.

4. 1-O status means alternative service. You state that you are not willing to serve the military in any fashion. That matches my status in WWII. I served five years in a CO internment camp, not much unlike a prison. Nowadays, this classification is almost impossible to receive unless you are a member of the Quaker church, or one similar, or you are the son of a minister.

Descriere

In 1968, Ben Sherman objected to serving as a soldier in Vietnam, but chose to become a medic. Mistakenly left for dead during a chopper rescue in a fierce firefight, Sherman became one of the very few army KIAs to return and share his experience.com.