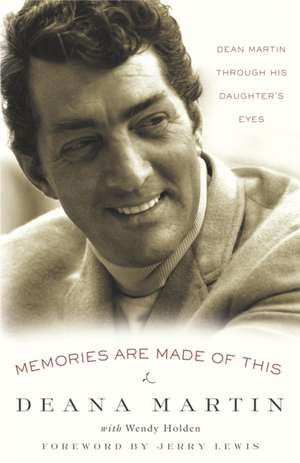

Memories Are Made of This: Dean Martin Through His Daughter's Eyes

Autor Deana Martin Jerry Lewis Wendy Holdenen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 oct 2005

In this heartfelt memoir, Deana recalls the constantly changing blended family that marked her youth, along with the unexpected moments of silliness and tenderness that this unusual Hollywood family shared. She candidly reveals the impact of Dean’s fame and characteristic aloofness, but delights in sharing wonderful, never-before-told stories about her father and his pallies known as the Rat Pack. This enchanting account of life as the daughter of one of Hollywood’s sexiest icons will leave you entertained, delighted, and nostalgic for a time gone by.

Preț: 91.34 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 137

Preț estimativ în valută:

17.48€ • 18.18$ • 14.43£

17.48€ • 18.18$ • 14.43£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400098330

ISBN-10: 1400098335

Pagini: 298

Ilustrații: 16-PAGE PHOTO INSERT; 30 B&W PH

Dimensiuni: 132 x 201 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.34 kg

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

ISBN-10: 1400098335

Pagini: 298

Ilustrații: 16-PAGE PHOTO INSERT; 30 B&W PH

Dimensiuni: 132 x 201 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.34 kg

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

Notă biografică

Deana Martin is an actress, entertainer, and author living with her husband in Beverly Hills, California. She is the director of the Deana Martin Foundation and the producer and driving force behind the annual Dean Martin Festival. Visit Deana on the Web at deanamartin.com.

Extras

Chapter One

Inside each of us is a small, dark place we can escape to when we're in pain. It is a silent sanctuary where comforting thoughts and memories wash over us, providing a soothing balm for the fear we're feeling inside. I first discovered mine when I was quite small. Cared for by an aunt while my mother disappeared for three days, I was sent to live with my father, a man I barely knew despite the name I bore.

I can vividly recall standing in the foyer of his opulent Beverly Hills mansion, along with three big boxes of clothes belonging to me and my two older sisters. A woman I knew as my stepmother picked up each item between her thumb and forefinger. "No, not this," she'd say, or, "This looks clean, we'll keep it," or-with a sympathetic look-"This can go to Goodwill." One of the boxes was mine, and

I stood staring at my only possessions being picked over and graded.

That first interminable summer in my father's house, I remained completely mute, breaking my silence only occasionally to whisper my fears to my sisters, from whom I became inseparable. My arms were pocked with hives, my skin raw from nervous scratching. While my father worked hard to maintain his position in Hollywood, revered by his millions of fans, his little Deana sat clutching the banisters every night. Dressed in one of my stepmother's baby-doll nighties, I dripped silent tears on the top step of his grand staircase, grieving for a loss too enormous for a nine-year-old child to comprehend.

On August 19, 1948, the day I was born in the Leroy Sanatorium, New York City, my father was busy doing what he did best. I emerged into the world at the very same moment a desperate woman threw herself from the window of the Russian embassy across the street. The media throng that gathered outside to cover the mystery suicide had no idea that Dean Martin's fourth child was bawling for attention just feet away.

Dad was on the other end of the country at the time, with his comedy partner, Jerry Lewis, playing at Slapsy Maxie's Café, a popular new nightclub on Wilshire Boulevard in Los Angeles. Theirs was the hottest ticket in town, and regularly filling front-row seats were friends like Humphrey Bogart, Tony Curtis, and Janet Leigh. Sitting alongside them would be stars like Fred Astaire, Clark Gable, Joan Crawford, Jane Wyman, James Cagney, and Gary Cooper, as well as just about every studio head and entertainment executive in town. Dad opened each show with a song. The minute he walked out onto that stage, the atmosphere was electric. His image, style, magnetism, class, and talent just lit up the club. Hollywood's brightest settled back into their seats, eagerly anticipating what lay ahead.

Dad and Jerry were superstars, earning around ten thousand dollars a week just after the end of the Second World War. They were about to sign a ten-movie, five-year deal with Paramount Studios worth $1,250,000. They also had a separate recording contract with Capitol Records and a radio deal with NBC. With three young children and my recent arrival, Dad was finally succeeding in paying off the debts that had dogged him for years, and funding the fairy-tale lifestyle he hoped to create for us all.

My mother, Betty, called Dad at the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel the night I was born to tell him he had a new daughter to add to his family. He was so deeply asleep when he took the call that he thought it was someone fooling around and hung up. Hours later, Dad rang back to see if his hazy memory of the previous night was correct. It was true. Mother had given him another baby girl. Between them, they settled on the name Deana Angela. Dad had always wanted at least some of his children to be named after him. Having successfully chosen the names Craig, Gail, and Claudia, Mother was only too happy to comply with Dad's request. At the hospital, the registrar misspelled my name, writing it as Dina on my birth certificate, much to Mother's annoyance. It was a mistake that was to be repeated throughout my life. When the gossip columnist Walter Winchell wrote in his Sunday column that my name was Dinah, my mother was exasperated. She sang the line from the song, "Dinah? Is there anyone finah in the state of Carolina?" and muttered, "Can't Winchell get anything right?"

It was two months before my father finally met me. His West Coast debut of The Martin & Lewis Show and his first movie role with Jerry in the film My Friend Irma kept him more than three thousand miles from 315 West 106th Street and Riverside, New York. That was where I shared an apartment with my mother, brother, and sisters and our housekeeper, Sue. Staying with us were my maternal grandmother, Gertrude, and my young aunts Anne and Barbara, who'd come from Philadelphia to help with my arrival. In the apartment above us was the singer Lena Horne, whose children played with us from an early age.

I finally came face to face with my father in Philadelphia, where Patti Lewis, Jerry's wife, accompanied the Martin family to a long-awaited reunion. Having taken me in his arms, he beamed adoringly into my big hazel eyes. Dad then announced that we were all moving to California. We returned to New York almost immediately to start packing, while my mother's family traveled home, their task complete. It was an emotional parting. To add to the tears, Mother's close friend, the actor Jackie Cooper, came to bid her good-bye.

"I wish you weren't going to Hollywood, Betty," he told her, giving her a warm embrace. "I just know it's gonna break your heart." Mother wondered what he knew.

For a brief period after my arrival, my parents enjoyed real happiness. Dad loved being a family man, and reveled in being a star. He could hardly believe how much his fortunes had changed. "Who'd have thunk it?" he would say. "For a boy from Steubenville, Ohio?"

He was always proud of where he came from, and mentioned it whenever he could. My grandfather Gaetano Crocetti had traveled to Steubenville shortly after arriving at Ellis Island in New York in 1913. A nineteen-year-old farm laborer, he came from Montesilvano, Italy, near Pescara on the Adriatic coast, following his two elder brothers to eastern Ohio. Steubenville was thirty-five miles west of Pittsburgh and had a large Italian immigrant population. Once settled, my grandfather became a barber. He embraced his new life but never lost his impenetrable Italian accent or his love for the old country.

My grandmother Angela Barra was born in Fernwood, Ohio, to parents who emigrated from Italy. She was raised by German nuns who taught her all the things that a young lady needed to know: The art of cooking, caring for a home, and, most important, they taught her how to sew. This was a skill, that she developed into a lucrative profession, as she became known as the finest seamstress in the region. Because of her, all of the boys in the neighborhood had beautifully handcrafted clothes, either new or altered from older suits. When we were children she made many of our finest outfits, all matching, and it was she who gave my father his impeccable sense of style. She also gave my grandfather his American nickname "Guy." On Sunday, October 25, 1914, at the age of sixteen, Angela married Guy at St. Anthony of Padua Church in Steubenville, Ohio. Their first child, Guglielmo, known to me as Uncle Bill, was born on June 24, 1916. Dad, who was baptized Dino Crocetti at the same church, was their second child. He was born June 7, 1917.

My grandmother was an excellent homemaker and a wonderful cook. Her sons were raised on traditional Italian cuisine such as spaghetti and meatballs, veal or sausage with peppers, and Dad's favorite-pasta fagioli. My grandfather was a respected barber, and his sons were never lacking for anything. All he ever wanted was their health and happiness. He also hoped that one day they might work alongside him in his barbershop.

Dad grew up in a close-knit neighborhood that served as an extended family. With his cousins John, Archie, and Robert, he played bocce ball and baseball in the lots behind their houses and swam in the Ohio River. There was church every Sunday, where Dad and Uncle Bill were altar boys; Boy Scouts, where he was the drummer; and the Sons of Italy social events. Until he was five years old, Dad spoke predominantly Italian, but that changed when he started going to school.

Learning English as a second language gave Dad a slow and easy style of speaking that remained with him for the rest of his life. Like all children, he began picking up phrases and expressions from his school friends and soon sounded just like them. Unlike his studious brother, Dad spent much of his spare time watching westerns at the local movie house, the Olympic. Sometimes he would hang out at the poolrooms and nightclubs that were opening to cater to the increasing numbers of steelworkers in the town, which became known as "Little Chicago." It was great entertainment, and all done openly within a few yards of his father's shop.

For a time some of Dad's friends joked that the only chair he was heading for was not the swiveling type in his father's barbershop. Dad even added a funny line about that into the song Mr. Wonderful years later, that went, "Back home in Steubenville, they're doubting all this, I swear. / They're still betting six-to-five I get the chair."

Dad once told an interviewer, "I had a great time growing up in Steubenville. I had everything I could possibly want-women, music, nightclubs, and liquor-and to think I had all of that when I was only thirteen."

My father learned from an early age that charm, good looks, and a smile could help him find everything from employment to hot bread at the Steubenville Bakery. He was, at different times, a milkman, a gas station attendant, and a store assistant.

He loved to sing, which he did at any opportunity, never passing up an invitation to entertain. He had a beautiful voice and enjoyed sharing it. The idea of making a living from singing first came to him when some friends pushed him onto the stage of a club called Walker's Café. He was sixteen. "Go on," they urged, "you can do it."

Cracking jokes between songs, with lines like "You should see my girlfriend, she has such beautiful teeth . . . both of them!"-Dad won over the crowd and soon started to pick up a few extra dollars singing at other venues around town. His role models were the Mills Brothers, who were fellow Ohioans, and Bing Crosby, whose records he played on a wind-up gramophone until he wore them out. Dad looked good and sang great, was well mannered, and had impeccable taste in clothes and girls. The combination made for a heady mix.

But the salary for a nightclub singer was meager at best. Forever humming tunes in his snap-brimmed hat, he began running errands for those making the most of Prohibition. He did everything from dealing at illegal card games to delivering bootleg whiskey throughout the area-the alcohol he claimed was so potent he could have run his car on it. He was a card dealer at the Rex Cigar Store, where he slipped so many silver dollars down his trouser legs and into shoes that he jangled when he walked. It was money his bosses didn't begrudge him, and which he quickly spent.

My aunt Violet used to say to him, "Dino, you never have any money."

He'd smile and reply, "I don't need money, Vi, I'm good looking."

Dad kept working, taking on different jobs, and accepting donations from friends who subsidized his pay so that he would keep singing. His only alternative was a career in the steel mills of Ohio and West Virginia-something he tried briefly. "I couldn't breathe in that place," Dad told me many years later, shaking his head. "I have nothing but respect for those guys. They're tough, but it wasn't for me."

He took up prizefighting briefly, under the pseudonym Kid Crochet, for ten dollars a match, breaking and permanently disfiguring the little finger on his right hand. He traveled the state, working as a croupier or a roulette stickman in numerous clubs across Ohio. By the time he was in his late teens, he was a worldly-wise young man earning twice as much as his father. He knew what he wanted-the world beyond the river. The dream was crystallized by a road trip to California with a friend in 1936. There he soaked up the atmosphere of Hollywood and wondered wistfully if one day he would be part of its magic.

His greatest desire was to pursue his singing career, and in 1939 he was finally offered a full-time job as the lead singer in the Ernie McKay Band in Columbus, Ohio. He was twenty-two. It was Ernie who gave him his first stage name, Dino Martini, in the hope of cashing in on the popularity of a heartthrob Italian singer named Nino Martini. Not long afterward, Dad was lured to Cleveland by Sammy Watkins and his orchestra. Sammy insisted on another name change, and this time it would stick. In a rented tuxedo and under an entirely new identity-Dean Martin-Dad sang the liltingly romantic songs that were to become his own. The stars were aligning.

It was 1941 and my mother, Elizabeth (Betty) MacDonald, was eighteen years old and a student in Swarthmore, Pennsylvania, when she first met Dad. Pretty, a world-class lacrosse athlete with a good singing voice and a tremendous sense of fun, she was one of five sisters much admired by the local young men. She was in Cleveland with her father, Bill MacDonald, who was being relocated there as a senior salesman for Schenley Whisky.

It was in the Vogue Room of the Hollenden Hotel where Dad was rehearsing that my mother first set eyes on him. Twenty-three years old, with dark wavy hair, and billed as "The Boy with the Tall, Dark, Handsome Voice," Dad was the best-looking man she'd ever seen. The mutual attraction was instant, and Dad fell for the Irish twinkle in Mother's eyes.

As an added insurance policy, Mother-who, having four sisters, knew how to attract attention-arrived at his show later that night wearing a big red sombrero. "Just to make sure he noticed me," she'd say, glowing from the memory.

From the Hardcover edition.

Inside each of us is a small, dark place we can escape to when we're in pain. It is a silent sanctuary where comforting thoughts and memories wash over us, providing a soothing balm for the fear we're feeling inside. I first discovered mine when I was quite small. Cared for by an aunt while my mother disappeared for three days, I was sent to live with my father, a man I barely knew despite the name I bore.

I can vividly recall standing in the foyer of his opulent Beverly Hills mansion, along with three big boxes of clothes belonging to me and my two older sisters. A woman I knew as my stepmother picked up each item between her thumb and forefinger. "No, not this," she'd say, or, "This looks clean, we'll keep it," or-with a sympathetic look-"This can go to Goodwill." One of the boxes was mine, and

I stood staring at my only possessions being picked over and graded.

That first interminable summer in my father's house, I remained completely mute, breaking my silence only occasionally to whisper my fears to my sisters, from whom I became inseparable. My arms were pocked with hives, my skin raw from nervous scratching. While my father worked hard to maintain his position in Hollywood, revered by his millions of fans, his little Deana sat clutching the banisters every night. Dressed in one of my stepmother's baby-doll nighties, I dripped silent tears on the top step of his grand staircase, grieving for a loss too enormous for a nine-year-old child to comprehend.

On August 19, 1948, the day I was born in the Leroy Sanatorium, New York City, my father was busy doing what he did best. I emerged into the world at the very same moment a desperate woman threw herself from the window of the Russian embassy across the street. The media throng that gathered outside to cover the mystery suicide had no idea that Dean Martin's fourth child was bawling for attention just feet away.

Dad was on the other end of the country at the time, with his comedy partner, Jerry Lewis, playing at Slapsy Maxie's Café, a popular new nightclub on Wilshire Boulevard in Los Angeles. Theirs was the hottest ticket in town, and regularly filling front-row seats were friends like Humphrey Bogart, Tony Curtis, and Janet Leigh. Sitting alongside them would be stars like Fred Astaire, Clark Gable, Joan Crawford, Jane Wyman, James Cagney, and Gary Cooper, as well as just about every studio head and entertainment executive in town. Dad opened each show with a song. The minute he walked out onto that stage, the atmosphere was electric. His image, style, magnetism, class, and talent just lit up the club. Hollywood's brightest settled back into their seats, eagerly anticipating what lay ahead.

Dad and Jerry were superstars, earning around ten thousand dollars a week just after the end of the Second World War. They were about to sign a ten-movie, five-year deal with Paramount Studios worth $1,250,000. They also had a separate recording contract with Capitol Records and a radio deal with NBC. With three young children and my recent arrival, Dad was finally succeeding in paying off the debts that had dogged him for years, and funding the fairy-tale lifestyle he hoped to create for us all.

My mother, Betty, called Dad at the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel the night I was born to tell him he had a new daughter to add to his family. He was so deeply asleep when he took the call that he thought it was someone fooling around and hung up. Hours later, Dad rang back to see if his hazy memory of the previous night was correct. It was true. Mother had given him another baby girl. Between them, they settled on the name Deana Angela. Dad had always wanted at least some of his children to be named after him. Having successfully chosen the names Craig, Gail, and Claudia, Mother was only too happy to comply with Dad's request. At the hospital, the registrar misspelled my name, writing it as Dina on my birth certificate, much to Mother's annoyance. It was a mistake that was to be repeated throughout my life. When the gossip columnist Walter Winchell wrote in his Sunday column that my name was Dinah, my mother was exasperated. She sang the line from the song, "Dinah? Is there anyone finah in the state of Carolina?" and muttered, "Can't Winchell get anything right?"

It was two months before my father finally met me. His West Coast debut of The Martin & Lewis Show and his first movie role with Jerry in the film My Friend Irma kept him more than three thousand miles from 315 West 106th Street and Riverside, New York. That was where I shared an apartment with my mother, brother, and sisters and our housekeeper, Sue. Staying with us were my maternal grandmother, Gertrude, and my young aunts Anne and Barbara, who'd come from Philadelphia to help with my arrival. In the apartment above us was the singer Lena Horne, whose children played with us from an early age.

I finally came face to face with my father in Philadelphia, where Patti Lewis, Jerry's wife, accompanied the Martin family to a long-awaited reunion. Having taken me in his arms, he beamed adoringly into my big hazel eyes. Dad then announced that we were all moving to California. We returned to New York almost immediately to start packing, while my mother's family traveled home, their task complete. It was an emotional parting. To add to the tears, Mother's close friend, the actor Jackie Cooper, came to bid her good-bye.

"I wish you weren't going to Hollywood, Betty," he told her, giving her a warm embrace. "I just know it's gonna break your heart." Mother wondered what he knew.

For a brief period after my arrival, my parents enjoyed real happiness. Dad loved being a family man, and reveled in being a star. He could hardly believe how much his fortunes had changed. "Who'd have thunk it?" he would say. "For a boy from Steubenville, Ohio?"

He was always proud of where he came from, and mentioned it whenever he could. My grandfather Gaetano Crocetti had traveled to Steubenville shortly after arriving at Ellis Island in New York in 1913. A nineteen-year-old farm laborer, he came from Montesilvano, Italy, near Pescara on the Adriatic coast, following his two elder brothers to eastern Ohio. Steubenville was thirty-five miles west of Pittsburgh and had a large Italian immigrant population. Once settled, my grandfather became a barber. He embraced his new life but never lost his impenetrable Italian accent or his love for the old country.

My grandmother Angela Barra was born in Fernwood, Ohio, to parents who emigrated from Italy. She was raised by German nuns who taught her all the things that a young lady needed to know: The art of cooking, caring for a home, and, most important, they taught her how to sew. This was a skill, that she developed into a lucrative profession, as she became known as the finest seamstress in the region. Because of her, all of the boys in the neighborhood had beautifully handcrafted clothes, either new or altered from older suits. When we were children she made many of our finest outfits, all matching, and it was she who gave my father his impeccable sense of style. She also gave my grandfather his American nickname "Guy." On Sunday, October 25, 1914, at the age of sixteen, Angela married Guy at St. Anthony of Padua Church in Steubenville, Ohio. Their first child, Guglielmo, known to me as Uncle Bill, was born on June 24, 1916. Dad, who was baptized Dino Crocetti at the same church, was their second child. He was born June 7, 1917.

My grandmother was an excellent homemaker and a wonderful cook. Her sons were raised on traditional Italian cuisine such as spaghetti and meatballs, veal or sausage with peppers, and Dad's favorite-pasta fagioli. My grandfather was a respected barber, and his sons were never lacking for anything. All he ever wanted was their health and happiness. He also hoped that one day they might work alongside him in his barbershop.

Dad grew up in a close-knit neighborhood that served as an extended family. With his cousins John, Archie, and Robert, he played bocce ball and baseball in the lots behind their houses and swam in the Ohio River. There was church every Sunday, where Dad and Uncle Bill were altar boys; Boy Scouts, where he was the drummer; and the Sons of Italy social events. Until he was five years old, Dad spoke predominantly Italian, but that changed when he started going to school.

Learning English as a second language gave Dad a slow and easy style of speaking that remained with him for the rest of his life. Like all children, he began picking up phrases and expressions from his school friends and soon sounded just like them. Unlike his studious brother, Dad spent much of his spare time watching westerns at the local movie house, the Olympic. Sometimes he would hang out at the poolrooms and nightclubs that were opening to cater to the increasing numbers of steelworkers in the town, which became known as "Little Chicago." It was great entertainment, and all done openly within a few yards of his father's shop.

For a time some of Dad's friends joked that the only chair he was heading for was not the swiveling type in his father's barbershop. Dad even added a funny line about that into the song Mr. Wonderful years later, that went, "Back home in Steubenville, they're doubting all this, I swear. / They're still betting six-to-five I get the chair."

Dad once told an interviewer, "I had a great time growing up in Steubenville. I had everything I could possibly want-women, music, nightclubs, and liquor-and to think I had all of that when I was only thirteen."

My father learned from an early age that charm, good looks, and a smile could help him find everything from employment to hot bread at the Steubenville Bakery. He was, at different times, a milkman, a gas station attendant, and a store assistant.

He loved to sing, which he did at any opportunity, never passing up an invitation to entertain. He had a beautiful voice and enjoyed sharing it. The idea of making a living from singing first came to him when some friends pushed him onto the stage of a club called Walker's Café. He was sixteen. "Go on," they urged, "you can do it."

Cracking jokes between songs, with lines like "You should see my girlfriend, she has such beautiful teeth . . . both of them!"-Dad won over the crowd and soon started to pick up a few extra dollars singing at other venues around town. His role models were the Mills Brothers, who were fellow Ohioans, and Bing Crosby, whose records he played on a wind-up gramophone until he wore them out. Dad looked good and sang great, was well mannered, and had impeccable taste in clothes and girls. The combination made for a heady mix.

But the salary for a nightclub singer was meager at best. Forever humming tunes in his snap-brimmed hat, he began running errands for those making the most of Prohibition. He did everything from dealing at illegal card games to delivering bootleg whiskey throughout the area-the alcohol he claimed was so potent he could have run his car on it. He was a card dealer at the Rex Cigar Store, where he slipped so many silver dollars down his trouser legs and into shoes that he jangled when he walked. It was money his bosses didn't begrudge him, and which he quickly spent.

My aunt Violet used to say to him, "Dino, you never have any money."

He'd smile and reply, "I don't need money, Vi, I'm good looking."

Dad kept working, taking on different jobs, and accepting donations from friends who subsidized his pay so that he would keep singing. His only alternative was a career in the steel mills of Ohio and West Virginia-something he tried briefly. "I couldn't breathe in that place," Dad told me many years later, shaking his head. "I have nothing but respect for those guys. They're tough, but it wasn't for me."

He took up prizefighting briefly, under the pseudonym Kid Crochet, for ten dollars a match, breaking and permanently disfiguring the little finger on his right hand. He traveled the state, working as a croupier or a roulette stickman in numerous clubs across Ohio. By the time he was in his late teens, he was a worldly-wise young man earning twice as much as his father. He knew what he wanted-the world beyond the river. The dream was crystallized by a road trip to California with a friend in 1936. There he soaked up the atmosphere of Hollywood and wondered wistfully if one day he would be part of its magic.

His greatest desire was to pursue his singing career, and in 1939 he was finally offered a full-time job as the lead singer in the Ernie McKay Band in Columbus, Ohio. He was twenty-two. It was Ernie who gave him his first stage name, Dino Martini, in the hope of cashing in on the popularity of a heartthrob Italian singer named Nino Martini. Not long afterward, Dad was lured to Cleveland by Sammy Watkins and his orchestra. Sammy insisted on another name change, and this time it would stick. In a rented tuxedo and under an entirely new identity-Dean Martin-Dad sang the liltingly romantic songs that were to become his own. The stars were aligning.

It was 1941 and my mother, Elizabeth (Betty) MacDonald, was eighteen years old and a student in Swarthmore, Pennsylvania, when she first met Dad. Pretty, a world-class lacrosse athlete with a good singing voice and a tremendous sense of fun, she was one of five sisters much admired by the local young men. She was in Cleveland with her father, Bill MacDonald, who was being relocated there as a senior salesman for Schenley Whisky.

It was in the Vogue Room of the Hollenden Hotel where Dad was rehearsing that my mother first set eyes on him. Twenty-three years old, with dark wavy hair, and billed as "The Boy with the Tall, Dark, Handsome Voice," Dad was the best-looking man she'd ever seen. The mutual attraction was instant, and Dad fell for the Irish twinkle in Mother's eyes.

As an added insurance policy, Mother-who, having four sisters, knew how to attract attention-arrived at his show later that night wearing a big red sombrero. "Just to make sure he noticed me," she'd say, glowing from the memory.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“From her heart, Deana Martin has told a frank and honest account of what her life was like with her famous father and family. It has been a wild ride, with lots of ups and downs, written with honesty, love, and understanding.” —Regis Philbin

Descriere

Martin presents a heartfelt memoir of her father, recalling her early childhood, when she and her siblings were left in the erratic care of Dean's loving but alcoholic first wife, the constantly changing blended family that marked her youth, along with the unexpected moments of silliness and tenderness that this unusual Hollywood family shared.