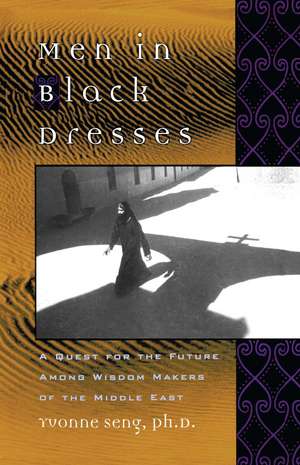

Men in Black Dresses: A Quest for the Future Among Wisdom-Makers of the Middle East

Autor Yvonne L. Sengen Limba Engleză Paperback – 18 noi 2003

Men In Black Dresses takes the reader behind the walls of desert monasteries, Sufi enclaves, ancient cathedrals and mosques -- where the author knocks, uninvited, and waits for the wise men to allow her in. Once inside, they discuss the universal concerns of the environment and the Internet, the building of a global community, and the education of coming generations, as well as the state of the human spirit.

Preț: 120.63 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 181

Preț estimativ în valută:

23.08€ • 23.95$ • 19.30£

23.08€ • 23.95$ • 19.30£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 22 februarie-08 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780743477260

ISBN-10: 074347726X

Pagini: 304

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Ediția:Original

Editura: Gallery Books

Colecția Gallery Books

Locul publicării:New York, United States

ISBN-10: 074347726X

Pagini: 304

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Ediția:Original

Editura: Gallery Books

Colecția Gallery Books

Locul publicării:New York, United States

Notă biografică

Yvonne Seng, Ph.D., is a cultural historian specializing in the Middle East and Turkey. Based in Washington, D.C., she has taught courses on peace studies at American University's Center for Global Peace, and on religion, history and Islamic culture at Georgetown and Princeton Universities and Wesley Theological Seminary. In 2000, she was a speaker at the State of the World Forum's special session on faith and technology. Born in Australia, she has worked and traveled widely in the Middle East.

Extras

Chapter One: The Nile Train

This is Cairo, Mother of the World, as Egyptians fondly call her. It's 1984. And I'm having trouble with my eyes.

In the Middle East, as in the Mediterranean in general, eyes have a secret language that my university professors never explained. Entire codes hide in the raising of an eyebrow, in the batting of lashes, and in full-frontal eye contact, that stirs up a slurry of self-consciousness and anger inside me. Throughout my life I've always felt different, but that was my internal landscape. Here, I am visibly different; tall and sandy blond, I stand out like a stevedore at a tea party.

Over the past months, I've found myself lowering my own eyes. I haven't seen the sky in weeks. And now that I have for a few short minutes, I'll be damned if I'm going to lower them again.

The old man's eyes on the Nile train, however, are more probing and direct than any I've yet experienced. Rheumy with cataracts, red-rimmed and swollen from decades of desert sand no longer brushed away, they are at once cold and hot, enforcing a distance yet drawing me toward the fire. They take no interest in my hair, my skin, even my own eyes. These are mere externalities. His eyes drill beneath my damp white shirt, down to somewhere deep inside me. Like a skilled archaeologist, the old man takes a sounding of my soul.

I can't move, but neither do I lower my eyes.

While he fingers my inner depths, I study the smacks of history recorded on his own skin. I meet him inch for inch. His face is distended with gravity like the wax of a molten candle through which God has pushed and pulled his fingers. The once-soft ground of this man's forehead is now graven with the prints of pain and sorrow. Sweat seeps from his sunken cheeks like moisture from the walls of an underground cave and trickles into a long growth of beard that separates head from body, person from person. This gray, barbed hedge says barricade. No small bird would dare mistake it for the cottony nest of Father Christmas.

In the background, a primitive air conditioner cranks into action and the train prepares to move forward. Still we continue our probes. Passengers in the last stages of settling in stuff their luggage overhead and into every available crevice around us, but we don't move. The tea maker rattles his kettle on a butane stove at the end of the corridor and stacks his mountain of small glass cups for when the brew is ready. The family across from us is tucking into their picnic breakfasts, unfurling leaves of fresh bread, unwrapping homemade sandwiches. Pungent smells of white cheese, cucumbers and boiled eggs, fresh tomatoes and olives are being quietly salted into my memory.

I dig for a clue to the old man's identity, his reason for being on the train and bothering me. A thick silver chain with an ornate medallion of the Virgin Mary pulls at his neck. The train lurches forward, thumps the metal sharply against his chest and I imagine that under that dusty black robe, his heart is callused from the weight of his profession.

So this is a holy man, I rationalize, but not a Muslim. A man of God. A Copt, an old monk, perhaps. The Egyptian deserts are riddled with monasteries, some of the world's earliest. Today's descendants of the ancient Copts, Egypt's first Christians, consider themselves the Sons of the Pharaohs, a living and vital link to the past. Predominantly Orthodox, they include a subminority of Catholics and Protestants. I'm not sure and don't care which he is. I just resent his intrusion.

God, I hunger for silence.

The inspection over, he speaks, first in French, then English.

"You will be pleased to sit with me," he says.

Not an invitation or an order, it is a statement of fact. The clucking of passengers, who have been observing us closely, warns me that any protest will be useless and, more than that, unwise. They've determined that I should give up my coveted window seat and sit with the holy man. By the communication of eyes, eyebrows, and a secret garrison of small, loaded gestures, they've taken charge of the next several hours of my life and, given a chance, will gladly take over the rest of it.

The train shuffles south along the Nile, and I gradually relax into the surrender of the journey and the company of my enforced companion. I crane past the holy man's full beard to see the desert villages but he blocks my view. For the first hour or so he is an enraptured etymologist, giving derivations of the village names in Greek, Italian, Coptic and Arabic interspersed with a similar excursion into terms used in the Church.

We pass inland and beyond time, and I become pupil to his teacher. He nods when I correctly answer the questions he poses about the history of the region and pauses to take mental note where I fail.

"Beni-Suweyf," he recites as the train passes through a village south of Cairo. "Do you know the meaning of this name?"

I'm a captive, therefore a wary, audience. He's leading me back to the safety of grade school, which I at first resist as I sense I'm being set up.

The spider at his trap, he pulls information from me about myself and gives none in return. Save that his name is Nuweiba.

My perverse colonial respect for old-timers eventually wins out. Do I know the meaning of Beni-Suweyf, he asks me again.

"Sons of the Sword," I reply, anxious to prove I have learned something during all that bloody self-flagellation in preparation for grad school at the University of Chicago.

"Yes, but do you know why they are called this?" he asks.

I shake my head out of respect. I'm learning that in Egypt, a question often serves as the introduction to a long story and that the richest moments come through listening. Some of the best storytellers, I'm also learning, are tricksters.

The old man doesn't bother to wait for a reply.

"They were given this title in the old days for their bravery in fighting," Nuweiba says and begins to pull me forward into the adventure of the past.

He rolls the coral of his rosary through his fingers as he recites the names of villages and towns like Hail Marys on that mystical string. From time to time he mops his face with the folded white handkerchief he pulls from the internal pocket of his dark robe. An unfortunate young man in an adjacent seat turns on a transistor radio but quickly shuts off the joyful crowing of a balladeer when met with the elder's scowl. The carriage moves forward in respectful hush commanded by the holy man's presence.

By midmorning the sun pierces the metal of the train carriage with no more resistance than a knife against a rusting can. Passengers lie slumped in their seats like deflatable dolls, their collars unbuttoned, moving one hand occasionally to fan themselves with wilted, humid newspapers.

We continue southward to the lulling motion of the train and the hypnotic click of the old man's prayer beads. His recitation of villages gradually slows.

Mallawi....

Manfalut....

The rest of the train is asleep, but we continue talking.

Nuweiba has assumed I am continuing on to that great tourist trek from Asyout to Luxor or Abu Simbel to see the monuments of the Pharaohs. I tell him, rather smugly, that the desert oasis is my destination.

He pauses.

We listen to the train track's hypnotic clack.

"On your own?" he finally asks. "Are you not afraid?"

One of the cardinal rules for women traveling alone is never -- never -- admit you're traveling alone. Always have someone meeting you at the station, an imaginary friend of a friend of the family. I can't be bothered with the lies anymore. I'm tired of manufacturing a happy nuclear family. I carry photos of my sister's children, selling them off as my own. I offer my wedding ring as false evidence of a glowing eight-year marriage.

The back of my shirt is stuck to the seat. Sweat trails down my calf.

"Afraid?" I reply. "Of what?"

He doesn't answer, but watches my steady flush. I've let my guard down and he's seen it.

Growing up in Australia, I didn't have to hop a train to find excitement. Our sprawling house in the tropics was built on stilts to catch the occasional breeze and the underhouse breezeway served as a cool place of banishment and solitude for an introspective child. In the long, rainy season, however, my refuge became a tribal meeting ground for a rite of passage.

When we siblings and cousins had exhausted the twenty-year supply of National Geographic, had grown tired of chasing each other around the sweeping, rain-soaked verandahs and disintegrated into warfare, my mother would appear in the doorway of the kitchen, where she had barricaded herself with her sister and a few gin fizzes. She would place one hand on her generous hip and point the other toward Hell.

"Go. Now," she would say with that calm authority she used with the cattle dogs, a couple of which were quartered below in the breezeway. "Go. Now. Go to Hell."

We were free.

For hours, as the drumming rain formed red-clay islands under the house, we were masters of our own antipodes. Occasionally a snake would float by in the runoff. If it were dead, it would become another prop in our games of Robinson Crusoe, Swiss Family Robinson, or the abridged version of Lord of the Flies. If alive, we'd step back with respect.

In this netherworld of restless children, our favorite game by far was "Spider," the Australian version of "Chicken." We'd hold our young sunburned hands above the nests of the venomous funnel-web and trap-door spiders to test our reflexes. If bitten, you had minutes before a particularly nasty death, and with no casualties so far, the odds rose with the water level. That was only the beginning. That's where boys became useful.

There were always older cousins or neighbors in some corner under the house gawking at a purloined copy of Playboy or attempting to smoke cigarettes made from rolled up newspaper or sugarcane leaves. At the peak of concentration, just before the spiders were wagered to leap at you, one of the boys would sneak up behind you and place a hand on your shoulder. You knew he was going to do it, but just not when.

You were never to scream.

Go bug-eyed, yes, but never scream.

That was part of the game, the fear of the half-known, the half-anticipated -- the spider's leap versus the hand on the shoulder -- as was the betting on the side. From upstairs, we could hear the laughter of our mothers and knew they were telling those grown-up stories that we never quite understood. Life was pretty good when you lived on the edge of a small world.

I'm now heading to a dot on the map you need a magnifying glass to read. I'm going to test the spider. I want that surge of adrenaline I felt as a child just to prove I'm still alive. My world is now larger, but the horizon is smaller.

My pretext for going to the oasis is to retrace the steps of a turn-of-the-century archaeologist, whose field notes I stumbled on while doing research at the Smithsonian. Buy me another drink and I'll tell you the truth. I'm going because I've been told I shouldn't. It's dangerous for a girl. Perfect. I'm going there to check my ability to survive alone again and to test my will to live. At this point in my life, it's divorce or suicide. Perhaps I exaggerate, but not much.

I'm not going to explain to the holy man on the Nile train about my childhood game of challenging the spiders. Neither am I going to tell him about the promise I made last year to the archaeologist's ghost after finding his yellowed field notes. About his fears of a disappearing world. Nuweiba is part of that world, and I am suddenly ashamed.

"Not particularly," I finally reply to his silence. "Why? Should I be afraid?"

The isolated oasis has its own laws, he explains, and can even be dangerous for a woman traveling alone.

In the days of the Pharaohs, it was a magical holding cell for their souls, halfway to the next world, before they became gods. Under Persian and Greek rule and well into the Christian era it was a bloody prison outpost, and until recent history, African slaves were castrated there and cauterized in the broiling sands. It sounds just fine.

I shrug. I appear impudent, I know, but the last thing I want is someone trying to interfere with my life. The next to last thing is another bloody lecture.

Instead of a lecture, however, the old man hits his fingertips together for emphasis, forms them into a tent, a pyramid, and begins to drive the wedge into the barrier I am quickly throwing up between us.

"So. That explains it. So you are going on a journey. A pilgrimage," he says like a bad fortune-teller. "Or are you planning to test fate?"

I don't reply. Save me. Surely I'm not that transparent.

"Then we should talk," he answers my silence.

He raises the palm of his hand toward me, whether in blessing or to stem my resistance, isn't important. Again, it is not a command, but a statement of fact. He turns immediately to the subject of religion, or rather, the soul I'm about to expose to fate like some bare-breasted pagan to the sun. Again, I guard my answers.

There is a story in my family, apocryphal, I'm sure. Once, as a child, when I'd been thrown out of school, I hurried home to my mother.

"Mum, am I a bloody little pagan?" I asked.

"Why, dear?" she responded.

"Because that's what the headmistress says I am," I replied.

I am told my mother didn't miss a beat but replied, straight-faced.

"No, child," she said. "You're not a pagan. You're just feral."

This I don't relate to the old man, but the memory makes me laugh and I begin to relax. Once we settle that I'm Christian, but not Catholic, the subject of my soul is no longer a pressing concern. That is, I'm within the fold and that's all that matters. There is no lecture.

To be an agnostic or an atheist, not to believe in a Greater Being outside (or carried inside) one's self, is for most in the Middle East an unnatural act. It means that you are alone and do not belong to a group, that you are without guidance from the wise ones, and therefore you suffer. The concept of a moral compass is strong here, an ancient compass that's calibrated with the poles of the community, its elders, and the wisdom of history they pass down.

On his part, the old man reveals that he is a humble member of the Catholic Coptic Church, from the diocese of Asyout. Nothing more. Nuweiba is insisting on his mysteries.

We resettle into our grudging companionship and solitary thoughts. We drift off into sleep, woken hours later by the tea-maker rattling through the carriage with his tray of hot tea.

Gray and ill-tempered, ripped from unsatisfying sleep, Nuweiba dips the end of a sugar cube into his glass of tea and watches it dissolve.

His black eyes latch onto mine as he sips the scalding tea.

"I have a secret," he finally says.

I don't answer. We all have secrets.

"A secret," he repeats, and concentrates his gaze on my face. "I am going to die."

He drops the remainder of the sugar cube into his tea and stirs it.

Why is he telling me this? We are all going to die; it's inevitable. In the last flush of extended youth, I'm more willing to lock horns in a challenge with death than to undergo the slow degradation of aging.

He looks past me, and quietly repeats: "I'm going home to die. This is my secret."

He isn't speaking to me; he's saying the words out loud to a stranger so he can hear them himself, perhaps for the first time. He's savoring them. The words, like the intimacies and addresses exchanged between strangers, are meant to fade at journey's end.

He has diabetes and the doctors say there is nothing they can do. He's just been to Cairo for prayers, twenty-two days in Cairo, and is returning home to die. Nobody else knows yet.

We both turn away and sink back into our own thoughts. He doesn't expect a reply and there is nothing I know how to say.

I am impressionable enough, however, to be flattered by the intimacy of this stranger, and to be entrusted with a secret by a holy man. He is wise enough to play me like a fiddle. In return for his intimacy, he exacts a promise.

"On your journey, you would like to see the future, then?" he asks, pulling gently on the thread he's created between us.

Of course I do. Secretly, don't we all? I pause, for I sense a sly conundrum, and nod out of curiosity of where the game is going.

"Then you must make this dying man a promise," he advances.

A pact with the devil? Have I been completely charmed by this old trickster in black robes?

I nod.

"Promise me you will return one day," he says slowly, staring me in the eyes. "Then will you see the future."

I'm slightly mystified by the extra care he's taking with his words.

"Why not today?" I ask. I'm not so sure about the future. If it looks good, however, I might stick around.

He thinks about it.

"When you return," he says. "But not today."

"Sure," I say. But I don't expect to survive the desert oasis.

"Good," is all he says, but with the finality of a deal struck. I've made a promise to a dying man, and damn, he is going to keep me to it.

I admit that I feel slightly manipulated, for he must know he's planted the seed of a dare, or challenge, I'd rise to. He knows, after all, about the game of spiders.

I add that promise to the one I made the previous year after reading the archaeologist's journal in the basement of the museum. That promise has led me to the train ride with the old man. I'm fast becoming an irretrievable link in a chain of good intentions.

As the Nile train approaches Asyout, a black-robed priest, who has been sitting nearby, comes forward to attend the elder. He hands the holy man a towering black hat and arranges its long veil as he helps him stand. From under the seat the attendant retrieves an ornate stave, its head decorated with silver, and places it in the elder's hand, which he then kisses.

The transformation complete, my traveling companion steps past me, without acknowledging my presence. He has become a magician. I no longer exist.

As the priest leads him down the aisle, strangers press forward to kiss the old man's hand. Their eyes are fixed on his, pleading for answers to their unspoken troubles. Some bow and try to touch or kiss the hem of his long dusty gown, others begin to cry, but he dismisses them, telling them coldly to stand. To have dignity. I catch the anger that flashes in his eyes and I'm chilled by the change in the holy man.

He walks past them toward a crowd of black-robed monks and priests who are waiting to claim him with unrestrained affection. He, in turn, is detached. He no longer belongs here. Like the ancients of the desert oasis to which I am going, he has already begun his journey to another world.

The dying old man is the venerable Bishop Nuweiba, the Catholic Coptic Bishop of Asyout and Upper Egypt. This is the beginning of Egypt's own Time of Troubles in which Islamic extremists are targeting Copts, Egypt's Christians, as agents of the West. This is part of the fallout of the Iranian Revolution. The responsibility for his community and the political interests of the Egyptian government are only two of the furrows engraved into his brow.

On the platform Bishop Nuweiba stops and glances over his shoulder. I'm standing near the train with my duffel and camera bags, watching the crowd disperse. He nods with some annoyance that he has to tell me to follow. Not an invitation or command, but a statement of fact. I am to have lunch with him and the monks at the cathedral before I head by bus into the desert.

Like a forgotten child, I am oddly pleased. Perhaps I'll keep my promise after all.

Copyright © 2003 by Yvonne J. Seng

This is Cairo, Mother of the World, as Egyptians fondly call her. It's 1984. And I'm having trouble with my eyes.

In the Middle East, as in the Mediterranean in general, eyes have a secret language that my university professors never explained. Entire codes hide in the raising of an eyebrow, in the batting of lashes, and in full-frontal eye contact, that stirs up a slurry of self-consciousness and anger inside me. Throughout my life I've always felt different, but that was my internal landscape. Here, I am visibly different; tall and sandy blond, I stand out like a stevedore at a tea party.

Over the past months, I've found myself lowering my own eyes. I haven't seen the sky in weeks. And now that I have for a few short minutes, I'll be damned if I'm going to lower them again.

The old man's eyes on the Nile train, however, are more probing and direct than any I've yet experienced. Rheumy with cataracts, red-rimmed and swollen from decades of desert sand no longer brushed away, they are at once cold and hot, enforcing a distance yet drawing me toward the fire. They take no interest in my hair, my skin, even my own eyes. These are mere externalities. His eyes drill beneath my damp white shirt, down to somewhere deep inside me. Like a skilled archaeologist, the old man takes a sounding of my soul.

I can't move, but neither do I lower my eyes.

While he fingers my inner depths, I study the smacks of history recorded on his own skin. I meet him inch for inch. His face is distended with gravity like the wax of a molten candle through which God has pushed and pulled his fingers. The once-soft ground of this man's forehead is now graven with the prints of pain and sorrow. Sweat seeps from his sunken cheeks like moisture from the walls of an underground cave and trickles into a long growth of beard that separates head from body, person from person. This gray, barbed hedge says barricade. No small bird would dare mistake it for the cottony nest of Father Christmas.

In the background, a primitive air conditioner cranks into action and the train prepares to move forward. Still we continue our probes. Passengers in the last stages of settling in stuff their luggage overhead and into every available crevice around us, but we don't move. The tea maker rattles his kettle on a butane stove at the end of the corridor and stacks his mountain of small glass cups for when the brew is ready. The family across from us is tucking into their picnic breakfasts, unfurling leaves of fresh bread, unwrapping homemade sandwiches. Pungent smells of white cheese, cucumbers and boiled eggs, fresh tomatoes and olives are being quietly salted into my memory.

I dig for a clue to the old man's identity, his reason for being on the train and bothering me. A thick silver chain with an ornate medallion of the Virgin Mary pulls at his neck. The train lurches forward, thumps the metal sharply against his chest and I imagine that under that dusty black robe, his heart is callused from the weight of his profession.

So this is a holy man, I rationalize, but not a Muslim. A man of God. A Copt, an old monk, perhaps. The Egyptian deserts are riddled with monasteries, some of the world's earliest. Today's descendants of the ancient Copts, Egypt's first Christians, consider themselves the Sons of the Pharaohs, a living and vital link to the past. Predominantly Orthodox, they include a subminority of Catholics and Protestants. I'm not sure and don't care which he is. I just resent his intrusion.

God, I hunger for silence.

The inspection over, he speaks, first in French, then English.

"You will be pleased to sit with me," he says.

Not an invitation or an order, it is a statement of fact. The clucking of passengers, who have been observing us closely, warns me that any protest will be useless and, more than that, unwise. They've determined that I should give up my coveted window seat and sit with the holy man. By the communication of eyes, eyebrows, and a secret garrison of small, loaded gestures, they've taken charge of the next several hours of my life and, given a chance, will gladly take over the rest of it.

The train shuffles south along the Nile, and I gradually relax into the surrender of the journey and the company of my enforced companion. I crane past the holy man's full beard to see the desert villages but he blocks my view. For the first hour or so he is an enraptured etymologist, giving derivations of the village names in Greek, Italian, Coptic and Arabic interspersed with a similar excursion into terms used in the Church.

We pass inland and beyond time, and I become pupil to his teacher. He nods when I correctly answer the questions he poses about the history of the region and pauses to take mental note where I fail.

"Beni-Suweyf," he recites as the train passes through a village south of Cairo. "Do you know the meaning of this name?"

I'm a captive, therefore a wary, audience. He's leading me back to the safety of grade school, which I at first resist as I sense I'm being set up.

The spider at his trap, he pulls information from me about myself and gives none in return. Save that his name is Nuweiba.

My perverse colonial respect for old-timers eventually wins out. Do I know the meaning of Beni-Suweyf, he asks me again.

"Sons of the Sword," I reply, anxious to prove I have learned something during all that bloody self-flagellation in preparation for grad school at the University of Chicago.

"Yes, but do you know why they are called this?" he asks.

I shake my head out of respect. I'm learning that in Egypt, a question often serves as the introduction to a long story and that the richest moments come through listening. Some of the best storytellers, I'm also learning, are tricksters.

The old man doesn't bother to wait for a reply.

"They were given this title in the old days for their bravery in fighting," Nuweiba says and begins to pull me forward into the adventure of the past.

He rolls the coral of his rosary through his fingers as he recites the names of villages and towns like Hail Marys on that mystical string. From time to time he mops his face with the folded white handkerchief he pulls from the internal pocket of his dark robe. An unfortunate young man in an adjacent seat turns on a transistor radio but quickly shuts off the joyful crowing of a balladeer when met with the elder's scowl. The carriage moves forward in respectful hush commanded by the holy man's presence.

By midmorning the sun pierces the metal of the train carriage with no more resistance than a knife against a rusting can. Passengers lie slumped in their seats like deflatable dolls, their collars unbuttoned, moving one hand occasionally to fan themselves with wilted, humid newspapers.

We continue southward to the lulling motion of the train and the hypnotic click of the old man's prayer beads. His recitation of villages gradually slows.

Mallawi....

Manfalut....

The rest of the train is asleep, but we continue talking.

Nuweiba has assumed I am continuing on to that great tourist trek from Asyout to Luxor or Abu Simbel to see the monuments of the Pharaohs. I tell him, rather smugly, that the desert oasis is my destination.

He pauses.

We listen to the train track's hypnotic clack.

"On your own?" he finally asks. "Are you not afraid?"

One of the cardinal rules for women traveling alone is never -- never -- admit you're traveling alone. Always have someone meeting you at the station, an imaginary friend of a friend of the family. I can't be bothered with the lies anymore. I'm tired of manufacturing a happy nuclear family. I carry photos of my sister's children, selling them off as my own. I offer my wedding ring as false evidence of a glowing eight-year marriage.

The back of my shirt is stuck to the seat. Sweat trails down my calf.

"Afraid?" I reply. "Of what?"

He doesn't answer, but watches my steady flush. I've let my guard down and he's seen it.

Growing up in Australia, I didn't have to hop a train to find excitement. Our sprawling house in the tropics was built on stilts to catch the occasional breeze and the underhouse breezeway served as a cool place of banishment and solitude for an introspective child. In the long, rainy season, however, my refuge became a tribal meeting ground for a rite of passage.

When we siblings and cousins had exhausted the twenty-year supply of National Geographic, had grown tired of chasing each other around the sweeping, rain-soaked verandahs and disintegrated into warfare, my mother would appear in the doorway of the kitchen, where she had barricaded herself with her sister and a few gin fizzes. She would place one hand on her generous hip and point the other toward Hell.

"Go. Now," she would say with that calm authority she used with the cattle dogs, a couple of which were quartered below in the breezeway. "Go. Now. Go to Hell."

We were free.

For hours, as the drumming rain formed red-clay islands under the house, we were masters of our own antipodes. Occasionally a snake would float by in the runoff. If it were dead, it would become another prop in our games of Robinson Crusoe, Swiss Family Robinson, or the abridged version of Lord of the Flies. If alive, we'd step back with respect.

In this netherworld of restless children, our favorite game by far was "Spider," the Australian version of "Chicken." We'd hold our young sunburned hands above the nests of the venomous funnel-web and trap-door spiders to test our reflexes. If bitten, you had minutes before a particularly nasty death, and with no casualties so far, the odds rose with the water level. That was only the beginning. That's where boys became useful.

There were always older cousins or neighbors in some corner under the house gawking at a purloined copy of Playboy or attempting to smoke cigarettes made from rolled up newspaper or sugarcane leaves. At the peak of concentration, just before the spiders were wagered to leap at you, one of the boys would sneak up behind you and place a hand on your shoulder. You knew he was going to do it, but just not when.

You were never to scream.

Go bug-eyed, yes, but never scream.

That was part of the game, the fear of the half-known, the half-anticipated -- the spider's leap versus the hand on the shoulder -- as was the betting on the side. From upstairs, we could hear the laughter of our mothers and knew they were telling those grown-up stories that we never quite understood. Life was pretty good when you lived on the edge of a small world.

I'm now heading to a dot on the map you need a magnifying glass to read. I'm going to test the spider. I want that surge of adrenaline I felt as a child just to prove I'm still alive. My world is now larger, but the horizon is smaller.

My pretext for going to the oasis is to retrace the steps of a turn-of-the-century archaeologist, whose field notes I stumbled on while doing research at the Smithsonian. Buy me another drink and I'll tell you the truth. I'm going because I've been told I shouldn't. It's dangerous for a girl. Perfect. I'm going there to check my ability to survive alone again and to test my will to live. At this point in my life, it's divorce or suicide. Perhaps I exaggerate, but not much.

I'm not going to explain to the holy man on the Nile train about my childhood game of challenging the spiders. Neither am I going to tell him about the promise I made last year to the archaeologist's ghost after finding his yellowed field notes. About his fears of a disappearing world. Nuweiba is part of that world, and I am suddenly ashamed.

"Not particularly," I finally reply to his silence. "Why? Should I be afraid?"

The isolated oasis has its own laws, he explains, and can even be dangerous for a woman traveling alone.

In the days of the Pharaohs, it was a magical holding cell for their souls, halfway to the next world, before they became gods. Under Persian and Greek rule and well into the Christian era it was a bloody prison outpost, and until recent history, African slaves were castrated there and cauterized in the broiling sands. It sounds just fine.

I shrug. I appear impudent, I know, but the last thing I want is someone trying to interfere with my life. The next to last thing is another bloody lecture.

Instead of a lecture, however, the old man hits his fingertips together for emphasis, forms them into a tent, a pyramid, and begins to drive the wedge into the barrier I am quickly throwing up between us.

"So. That explains it. So you are going on a journey. A pilgrimage," he says like a bad fortune-teller. "Or are you planning to test fate?"

I don't reply. Save me. Surely I'm not that transparent.

"Then we should talk," he answers my silence.

He raises the palm of his hand toward me, whether in blessing or to stem my resistance, isn't important. Again, it is not a command, but a statement of fact. He turns immediately to the subject of religion, or rather, the soul I'm about to expose to fate like some bare-breasted pagan to the sun. Again, I guard my answers.

There is a story in my family, apocryphal, I'm sure. Once, as a child, when I'd been thrown out of school, I hurried home to my mother.

"Mum, am I a bloody little pagan?" I asked.

"Why, dear?" she responded.

"Because that's what the headmistress says I am," I replied.

I am told my mother didn't miss a beat but replied, straight-faced.

"No, child," she said. "You're not a pagan. You're just feral."

This I don't relate to the old man, but the memory makes me laugh and I begin to relax. Once we settle that I'm Christian, but not Catholic, the subject of my soul is no longer a pressing concern. That is, I'm within the fold and that's all that matters. There is no lecture.

To be an agnostic or an atheist, not to believe in a Greater Being outside (or carried inside) one's self, is for most in the Middle East an unnatural act. It means that you are alone and do not belong to a group, that you are without guidance from the wise ones, and therefore you suffer. The concept of a moral compass is strong here, an ancient compass that's calibrated with the poles of the community, its elders, and the wisdom of history they pass down.

On his part, the old man reveals that he is a humble member of the Catholic Coptic Church, from the diocese of Asyout. Nothing more. Nuweiba is insisting on his mysteries.

We resettle into our grudging companionship and solitary thoughts. We drift off into sleep, woken hours later by the tea-maker rattling through the carriage with his tray of hot tea.

Gray and ill-tempered, ripped from unsatisfying sleep, Nuweiba dips the end of a sugar cube into his glass of tea and watches it dissolve.

His black eyes latch onto mine as he sips the scalding tea.

"I have a secret," he finally says.

I don't answer. We all have secrets.

"A secret," he repeats, and concentrates his gaze on my face. "I am going to die."

He drops the remainder of the sugar cube into his tea and stirs it.

Why is he telling me this? We are all going to die; it's inevitable. In the last flush of extended youth, I'm more willing to lock horns in a challenge with death than to undergo the slow degradation of aging.

He looks past me, and quietly repeats: "I'm going home to die. This is my secret."

He isn't speaking to me; he's saying the words out loud to a stranger so he can hear them himself, perhaps for the first time. He's savoring them. The words, like the intimacies and addresses exchanged between strangers, are meant to fade at journey's end.

He has diabetes and the doctors say there is nothing they can do. He's just been to Cairo for prayers, twenty-two days in Cairo, and is returning home to die. Nobody else knows yet.

We both turn away and sink back into our own thoughts. He doesn't expect a reply and there is nothing I know how to say.

I am impressionable enough, however, to be flattered by the intimacy of this stranger, and to be entrusted with a secret by a holy man. He is wise enough to play me like a fiddle. In return for his intimacy, he exacts a promise.

"On your journey, you would like to see the future, then?" he asks, pulling gently on the thread he's created between us.

Of course I do. Secretly, don't we all? I pause, for I sense a sly conundrum, and nod out of curiosity of where the game is going.

"Then you must make this dying man a promise," he advances.

A pact with the devil? Have I been completely charmed by this old trickster in black robes?

I nod.

"Promise me you will return one day," he says slowly, staring me in the eyes. "Then will you see the future."

I'm slightly mystified by the extra care he's taking with his words.

"Why not today?" I ask. I'm not so sure about the future. If it looks good, however, I might stick around.

He thinks about it.

"When you return," he says. "But not today."

"Sure," I say. But I don't expect to survive the desert oasis.

"Good," is all he says, but with the finality of a deal struck. I've made a promise to a dying man, and damn, he is going to keep me to it.

I admit that I feel slightly manipulated, for he must know he's planted the seed of a dare, or challenge, I'd rise to. He knows, after all, about the game of spiders.

I add that promise to the one I made the previous year after reading the archaeologist's journal in the basement of the museum. That promise has led me to the train ride with the old man. I'm fast becoming an irretrievable link in a chain of good intentions.

As the Nile train approaches Asyout, a black-robed priest, who has been sitting nearby, comes forward to attend the elder. He hands the holy man a towering black hat and arranges its long veil as he helps him stand. From under the seat the attendant retrieves an ornate stave, its head decorated with silver, and places it in the elder's hand, which he then kisses.

The transformation complete, my traveling companion steps past me, without acknowledging my presence. He has become a magician. I no longer exist.

As the priest leads him down the aisle, strangers press forward to kiss the old man's hand. Their eyes are fixed on his, pleading for answers to their unspoken troubles. Some bow and try to touch or kiss the hem of his long dusty gown, others begin to cry, but he dismisses them, telling them coldly to stand. To have dignity. I catch the anger that flashes in his eyes and I'm chilled by the change in the holy man.

He walks past them toward a crowd of black-robed monks and priests who are waiting to claim him with unrestrained affection. He, in turn, is detached. He no longer belongs here. Like the ancients of the desert oasis to which I am going, he has already begun his journey to another world.

The dying old man is the venerable Bishop Nuweiba, the Catholic Coptic Bishop of Asyout and Upper Egypt. This is the beginning of Egypt's own Time of Troubles in which Islamic extremists are targeting Copts, Egypt's Christians, as agents of the West. This is part of the fallout of the Iranian Revolution. The responsibility for his community and the political interests of the Egyptian government are only two of the furrows engraved into his brow.

On the platform Bishop Nuweiba stops and glances over his shoulder. I'm standing near the train with my duffel and camera bags, watching the crowd disperse. He nods with some annoyance that he has to tell me to follow. Not an invitation or command, but a statement of fact. I am to have lunch with him and the monks at the cathedral before I head by bus into the desert.

Like a forgotten child, I am oddly pleased. Perhaps I'll keep my promise after all.

Copyright © 2003 by Yvonne J. Seng

Recenzii

Peter Russell Author, The Global Brain and From Science to God Powerful and eloquent. Yvonne Seng's style takes us on a personal quest into the rich, but little explored, realm of Middle Eastern mysticism.

David Ignatius Associate editor and columnist, The Washington Post Yvonne Seng takes the reader on an exotic and enlightening journey to visit the mystical religious figures -- the Men in Black Dresses -- who guide the soul of the Arab world. Their ancient wisdom has timely relevance for the Western world.

David Ignatius Associate editor and columnist, The Washington Post Yvonne Seng takes the reader on an exotic and enlightening journey to visit the mystical religious figures -- the Men in Black Dresses -- who guide the soul of the Arab world. Their ancient wisdom has timely relevance for the Western world.