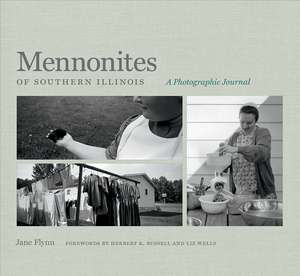

Mennonites of Southern Illinois: A Photographic Journal

Autor Jane Flynn Cuvânt înainte de Herbert K. Russell, Liz Liz Wellsen Limba Engleză Paperback – 24 iun 2024

Offering a glimpse into a world largely misunderstood by mainstream society, this book documents the period of eight years that Jane Flynn practiced with Mennonites in two different Southern Illinois communities: Stonefort, and Mount Pleasant in Anna. Despite her status as an outsider, Flynn was welcomed and allowed to photograph the Mennonites in their homes, making applesauce, farming, and beekeeping.

Escaping persecution from the Catholic Church in Europe, the Mennonites arrived in America in 1683, settling in what is now Pennsylvania. Today, they live in almost all 50 states, Canada, and South America. To reflect the Mennonites’ manual-labor lifestyle, Flynn processed her black-and-white photographs by hand and hand-printed them in a dark room. The imagery explores the Mennonites’ labors, leisure, and faith by documenting their homes, places of work and worship, and the Illinois Ozark landscape they inhabit.

Similar to the Amish and the Quakers, Mennonites consider the Bible the supreme authority and insist on a separation between church and state. To enact that separation, they distinguish themselves from society in speech, dress, business, recreation, education, pacifism, and by refusing to participate in politics. They believe in nonconformity to the world, discipleship, and being born again through adult baptism. With Mennonites of Southern Illinois, Jane Flynn provides representation for these closed communities and illustrates the Mennonites’ struggle to find and maintain balance between rustic and modern life while remaining faithful to their religious beliefs.

Preț: 137.95 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 207

Preț estimativ în valută:

26.40€ • 27.63$ • 21.84£

26.40€ • 27.63$ • 21.84£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 15-29 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780809339402

ISBN-10: 0809339404

Pagini: 152

Ilustrații: 93

Dimensiuni: 235 x 216 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.43 kg

Ediția:First Edition

Editura: Southern Illinois University Press

Colecția Southern Illinois University Press

ISBN-10: 0809339404

Pagini: 152

Ilustrații: 93

Dimensiuni: 235 x 216 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.43 kg

Ediția:First Edition

Editura: Southern Illinois University Press

Colecția Southern Illinois University Press

Notă biografică

Jane Flynn received her MFA in media arts with a focus on photography from Southern Illinois University Carbondale. Her work appears frequently in professional exhibitions in the United States and internationally, such as The Montgomery Photo Festival presented by the Society of Arts & Crafts, the Women's Caucus Exhibition of the World Record FotoFocus Biennial, and the 29th Cedarhurst Biennial. Recipient of the 2022 Merit Award in Black & White from the 2022 Montgomery Photo Festival, Flynn continues practicing photography and specializes in capturing her subjects in their natural, unedited form.

Extras

PREFACE

The Mennonites, or “plain people” as they refer to themselves, took as much interest in my presence in their community as I did in their presence in the larger community of southern Illinois. Despite having grown up in vastly different circumstances, our sharing of memories, stories of our home countries, of our different traditions, and of our different lifestyles became foundational in the development of relationships and subsequent friendships and my photographic representation of them. The resulting photographs are an intimate document of my experiences and relationships that developed over the past nine years spent to date with Mennonites in two small, rural communities, but principally in and around Mount Pleasant. The imagery should, however, not be considered as a complete documentation of all things Mennonite. While all Mennonites are Anabaptists, different churches have varying practices with regards to certain biblical principles. An example of this would be photography; the Stonefort/Carrier Mills community are very strict with regards to having their picture taken. They allowed me to photograph their businesses, and themselves at work. They would, however, not pose before my camera for a family portrait. Additionally, all of their daily discourse and church services are spoken in various forms of German, which further hampered my access to the community and church services. As such, the majority of my relationships and friendships were made within the Mount Pleasant community, who speak English within the home and church services.

The traditional practices of gender roles also had a significant influence on what I could and could not access within the community as a woman. As per Mark 10:1-12, women are considered subservient to men, and when married, they serve their husbands. God, man, woman is considered as the order of headship, as per biblical teachings. Women are highly respected for their domestic roles, working within the home once they are married, where it is not unusual to have as many as ten children; all children, regardless of their abilities, are considered gifts from God, and are lovingly welcomed into the community. Those unable to bear their own children will often adopt from outside the community, and raise their children as all Mennonite children are raised. Like all youth, they will then decide whether or not to be baptized, and therefore join the church, at an appropriate age. Biblical gender roles are taught to children from a young age; girls will usually work within the home, while boys may have chores on the farm or help their fathers. By the time children are old enough to walk and talk, boys will be sitting with their fathers, and girls with their mothers in church and social settings. When socializing in groups, women will usually interact together with their young children or babies, and the men and boys will sit and interact in a different area. These gender roles have influenced what I have and haven't had access to; for instance, I found myself largely socializing and working alongside women and children, but never within groups of men. To view the work is to view many (but not all) of my personal experiences of being present in a conservative practicing Christian community which upholds biblical values and practices of gender identity.

By acting in line with their practices and principles, I have been gracefully accepted into their community. I did not want to push worldly practices onto the community, in a vain effort to document areas where single women would not have otherwise been present, and as such the work documents experiences from a female oriented presence. The comfort my subjects have in front of my lens is a direct result of being so accepted into their ranks. This graceful acceptance is a result of not putting my subjects in a position of being uncomfortable or pushing their socially accepted roles and boundaries, and to do so would have undoubtedly produced a result very different from the images you see in this book. My subjects have always been gracious, kind, and accepting of my presence in the community, regardless of my outsider status, and the work visually reflects this; I have not tried to make uncomfortable or ugly imagery of my subjects, as this would be very much out of line with my experiences and personal friendships.

My first experience of this acceptance was when I first attended church at Mount Pleasant, having been invited following an interview with the minister, whom I first met at a Street Meeting on Southern Illinois University campus. Upon first entering the church, I was immediately struck by everyone's kindness; many people introduced themselves to me, and I was asked if I would like to sit next to various different women. Although in worldly apparel and appearing distinctly different from the women that I sat amongst, I was warmly welcomed into the service, as all guests are. This was my first taste of the true Christian kindness and acceptance that has characterized all my interactions with the community, despite my status as an 'outsider'. That Sunday morning I was, and continue to be, warmly welcomed into their church, their homes, and their businesses with true Christian kindness.

Periodically throughout the year, there are opportunities for the women to sign up as hostess to serve lunch after the service in their homes. Guests to the service (who may have travelled from many miles away) are invited, alongside friends and family from the church congregation. On my third visit to church, I was invited to lunch by Wanda Weaver, who I have always been close with since our first encounter that Sunday. After everyone ate, the women tidied up the kitchen; dishes were washed, dried and put away, while the table was returned to its original size by removing all the extra leaves and chairs added to accommodate the many guests. After tidying up, all the women sat down to visit in the living room. Wanda and I sat together, discussing various aspects of our lives. I asked her how many children she had; ten! That was the first time I knowingly met anyone who had raised ten children. They are all now grown and live throughout different states in the US. She shared with me a book on the Scottish landscape that she found in a thrift store, and I was able to identify many of the places depicted. She had many questions about life in the UK, and expressed her concern for me, living without any family nearby to help should I need any help or become unwell, so she wrote down her and Glen's contact information, on a small slip of paper that I still, to this day, keep in my wallet. When I write to her and Glen, I still get out that small slip to refer to their address. That seemingly small gesture of reaching out to me offering assistance with anything should I need it was so heartwarming, and a level of acceptance and kindness I had not ever come across before having known Glen and Wanda for such a short amount of time. Later, I would go on to spend most Sunday afternoons visiting their home after church service and spent many holidays there too, including Thanksgiving, a holiday which we do not celebrate in Scotland.

I would attend the Mount Pleasant church for eight more months, building friendships and attending lunch with various families within the community before being asked by my new friend Ruby Weaver if I ever had wished for a dress. Shortly after, we discovered we born only days apart, and so as a birthday gift, she sewed me a Mennonite dress. Known as a “cape dress”, in reference to the 'cape’ which is an additional layer of fabric, attached at the neckline, that covers the bust down to the waist, where it is sewn into the elastic casing. Functionally, it adds an additional layer of modesty to cover the women’s figure, as well as visually separating the wearer from worldly fashions.

This act of acceptance by the community was distinctly touching, given that I had never owned a handmade dress before. In exchange for my dress, I made Ruby a family portrait, showing Ruby, her husband, Titus, and their then seven-month old daughter, Erica. The use of a mechanically reproducible craft (the photograph) in exchange for a unique, one-off item can be seen as symbolic of our relationship and the corresponding worlds from which we belong. In a society where material goods become disposable, to have a one-off, unique dress is unusual.

Attending church weekly did not come without mixed reactions. My parents have taken a keen interest in my newfound relationships, while comments from many friends and close colleagues have been mixed. “Are you a Mennonite now?” is often asked in a strange tone, particularly after hearing I was gifted a dress. One friend went so far as to exclaim that we could no longer be friends should I become a member of the Mennonite church, which would be in stark contrast to the Mennonites acceptance of those different from themselves. As the Bible encourages, Mennonites practice Christian kindness to their neighbors, who they regularly interact with, visit with, and gift homemade foodstuffs. Those that have strayed from the community or have perhaps become lost on their journey as Christians are regularly prayed for at home and in prayer meetings held at the church. Many of my other friends found the stories and photos of my interactions fascinating, and viewers often asked me to take them to church, about how I became involved, and about my friendships.

As my relationships within the community grew, I was consistently struck by the misunderstandings about plain people by the majority of society. Among many things, the most striking include the belief that they are exempt from paying taxes, live “off the grid,” (a term I have deliberately chosen to use here for its myriad of mixed meanings and connotations) and do not register the births of their children. Although none of these assumptions are true, I mention them as they speak of the misunderstanding the general population has about plain people, who consider themselves to be in the world, but not of the world. As stated in Romans 12:2 “And be not conformed to this world: but be ye transformed by the renewing of your mind, that ye may prove what [is] that good, and acceptable, and perfect, will of God.” The world is considered a place to pass through, and while their salvation and subsequent entrance into heaven is not guaranteed, their strict adherence to biblical teachings, kindness, and unconditional acceptance of those who want to do right in the eyes of the Lord are something to be marveled at. They live a Bible-taught way of life as evidenced in every area of living: speech, dress, business, social purity, recreation, education, and non-participation in politics and warfare. They are strongly opposed to war, and are now given religious exemption from the United States’ military draft. They believe in the separation of church and state, nonconformity to the world, discipleship, and being born again by practicing adult baptism.

Some Mennonites refer to themselves as “The Quiet in the Land”, and it is a phrase I came across multiple times in the copious amounts of reading I did before approaching the church in Mount Pleasant. Quiet should not be taken literally, for their homes are often quite noisy—numerous children, friends, and neighbors often gather for meals—but the noise comes from the occupants rather than gadgets such as televisions and radios. In keeping with their lifestyle, it is believed that the television and radio spreads evil messages, and can therefore corrupt Christian beliefs. As such, children are found playing together, building things, or reading books. A favorite game is to play church! Those that are not old enough to read, or cannot read well, are always begging to have a story read to them. Story-telling is used for entertainment purposes as well as reinforcing biblical principles and practices, and there are many conservative Christian publishers that publish books especially for conservative Anabaptists, both for adults and children. These books often show characters in plain dress, in a rural setting, the sort of areas in which many plain communities live.

This quieter home experience, away from all the gadgets and modern 'smart' devices stands in stark contrast to the lives of many families today, who often use 'screen time' as a child minder, in an attempt to save two already overburdened parents the headache of having to entertain the children, having both spent the day at nine-to-five jobs. This all-too-real modern parental practice calls us to consider whether or not our current lifestyle is actually desirable, not to mention a practical approach, for our families. I had to ask myself, would our marriages last longer, our children be emotionally and physically healthier, and our lives be less materially focused if one parent were able to stay home?

My journey in meeting with, fellowshipping, and developing friendships in such a conservative Christian community has afforded me many opportunities to consider my current way of life, kindness and thoughtfulness towards others. Children are taught the acronym 'JOY', which stands for Jesus, Others, Yourself, and is the order in which they are taught to consider others. In contrast to these teachings, at the time of my first sermon in Mount Pleasant, I was single, without any dependents, and living with no family in the same country. I essentially had free rein on what I did with my time, my money, and my efforts. However, it was at a service about contentment that changed this for me. I distinctly remember being deeply touched by the idea of sacrifice, and how making small sacrifices would benefit others. After all, would we all really miss that twenty-dollar bill sitting in our wallets? Or would it be more beneficial to donate it to another cause? I couldn’t, honestly, even tell you what sum of money is in my wallet right now, which leads me to be believe that I wouldn’t miss it should it one day vanish.

[end of excerpt]

The Mennonites, or “plain people” as they refer to themselves, took as much interest in my presence in their community as I did in their presence in the larger community of southern Illinois. Despite having grown up in vastly different circumstances, our sharing of memories, stories of our home countries, of our different traditions, and of our different lifestyles became foundational in the development of relationships and subsequent friendships and my photographic representation of them. The resulting photographs are an intimate document of my experiences and relationships that developed over the past nine years spent to date with Mennonites in two small, rural communities, but principally in and around Mount Pleasant. The imagery should, however, not be considered as a complete documentation of all things Mennonite. While all Mennonites are Anabaptists, different churches have varying practices with regards to certain biblical principles. An example of this would be photography; the Stonefort/Carrier Mills community are very strict with regards to having their picture taken. They allowed me to photograph their businesses, and themselves at work. They would, however, not pose before my camera for a family portrait. Additionally, all of their daily discourse and church services are spoken in various forms of German, which further hampered my access to the community and church services. As such, the majority of my relationships and friendships were made within the Mount Pleasant community, who speak English within the home and church services.

The traditional practices of gender roles also had a significant influence on what I could and could not access within the community as a woman. As per Mark 10:1-12, women are considered subservient to men, and when married, they serve their husbands. God, man, woman is considered as the order of headship, as per biblical teachings. Women are highly respected for their domestic roles, working within the home once they are married, where it is not unusual to have as many as ten children; all children, regardless of their abilities, are considered gifts from God, and are lovingly welcomed into the community. Those unable to bear their own children will often adopt from outside the community, and raise their children as all Mennonite children are raised. Like all youth, they will then decide whether or not to be baptized, and therefore join the church, at an appropriate age. Biblical gender roles are taught to children from a young age; girls will usually work within the home, while boys may have chores on the farm or help their fathers. By the time children are old enough to walk and talk, boys will be sitting with their fathers, and girls with their mothers in church and social settings. When socializing in groups, women will usually interact together with their young children or babies, and the men and boys will sit and interact in a different area. These gender roles have influenced what I have and haven't had access to; for instance, I found myself largely socializing and working alongside women and children, but never within groups of men. To view the work is to view many (but not all) of my personal experiences of being present in a conservative practicing Christian community which upholds biblical values and practices of gender identity.

By acting in line with their practices and principles, I have been gracefully accepted into their community. I did not want to push worldly practices onto the community, in a vain effort to document areas where single women would not have otherwise been present, and as such the work documents experiences from a female oriented presence. The comfort my subjects have in front of my lens is a direct result of being so accepted into their ranks. This graceful acceptance is a result of not putting my subjects in a position of being uncomfortable or pushing their socially accepted roles and boundaries, and to do so would have undoubtedly produced a result very different from the images you see in this book. My subjects have always been gracious, kind, and accepting of my presence in the community, regardless of my outsider status, and the work visually reflects this; I have not tried to make uncomfortable or ugly imagery of my subjects, as this would be very much out of line with my experiences and personal friendships.

My first experience of this acceptance was when I first attended church at Mount Pleasant, having been invited following an interview with the minister, whom I first met at a Street Meeting on Southern Illinois University campus. Upon first entering the church, I was immediately struck by everyone's kindness; many people introduced themselves to me, and I was asked if I would like to sit next to various different women. Although in worldly apparel and appearing distinctly different from the women that I sat amongst, I was warmly welcomed into the service, as all guests are. This was my first taste of the true Christian kindness and acceptance that has characterized all my interactions with the community, despite my status as an 'outsider'. That Sunday morning I was, and continue to be, warmly welcomed into their church, their homes, and their businesses with true Christian kindness.

Periodically throughout the year, there are opportunities for the women to sign up as hostess to serve lunch after the service in their homes. Guests to the service (who may have travelled from many miles away) are invited, alongside friends and family from the church congregation. On my third visit to church, I was invited to lunch by Wanda Weaver, who I have always been close with since our first encounter that Sunday. After everyone ate, the women tidied up the kitchen; dishes were washed, dried and put away, while the table was returned to its original size by removing all the extra leaves and chairs added to accommodate the many guests. After tidying up, all the women sat down to visit in the living room. Wanda and I sat together, discussing various aspects of our lives. I asked her how many children she had; ten! That was the first time I knowingly met anyone who had raised ten children. They are all now grown and live throughout different states in the US. She shared with me a book on the Scottish landscape that she found in a thrift store, and I was able to identify many of the places depicted. She had many questions about life in the UK, and expressed her concern for me, living without any family nearby to help should I need any help or become unwell, so she wrote down her and Glen's contact information, on a small slip of paper that I still, to this day, keep in my wallet. When I write to her and Glen, I still get out that small slip to refer to their address. That seemingly small gesture of reaching out to me offering assistance with anything should I need it was so heartwarming, and a level of acceptance and kindness I had not ever come across before having known Glen and Wanda for such a short amount of time. Later, I would go on to spend most Sunday afternoons visiting their home after church service and spent many holidays there too, including Thanksgiving, a holiday which we do not celebrate in Scotland.

I would attend the Mount Pleasant church for eight more months, building friendships and attending lunch with various families within the community before being asked by my new friend Ruby Weaver if I ever had wished for a dress. Shortly after, we discovered we born only days apart, and so as a birthday gift, she sewed me a Mennonite dress. Known as a “cape dress”, in reference to the 'cape’ which is an additional layer of fabric, attached at the neckline, that covers the bust down to the waist, where it is sewn into the elastic casing. Functionally, it adds an additional layer of modesty to cover the women’s figure, as well as visually separating the wearer from worldly fashions.

This act of acceptance by the community was distinctly touching, given that I had never owned a handmade dress before. In exchange for my dress, I made Ruby a family portrait, showing Ruby, her husband, Titus, and their then seven-month old daughter, Erica. The use of a mechanically reproducible craft (the photograph) in exchange for a unique, one-off item can be seen as symbolic of our relationship and the corresponding worlds from which we belong. In a society where material goods become disposable, to have a one-off, unique dress is unusual.

Attending church weekly did not come without mixed reactions. My parents have taken a keen interest in my newfound relationships, while comments from many friends and close colleagues have been mixed. “Are you a Mennonite now?” is often asked in a strange tone, particularly after hearing I was gifted a dress. One friend went so far as to exclaim that we could no longer be friends should I become a member of the Mennonite church, which would be in stark contrast to the Mennonites acceptance of those different from themselves. As the Bible encourages, Mennonites practice Christian kindness to their neighbors, who they regularly interact with, visit with, and gift homemade foodstuffs. Those that have strayed from the community or have perhaps become lost on their journey as Christians are regularly prayed for at home and in prayer meetings held at the church. Many of my other friends found the stories and photos of my interactions fascinating, and viewers often asked me to take them to church, about how I became involved, and about my friendships.

As my relationships within the community grew, I was consistently struck by the misunderstandings about plain people by the majority of society. Among many things, the most striking include the belief that they are exempt from paying taxes, live “off the grid,” (a term I have deliberately chosen to use here for its myriad of mixed meanings and connotations) and do not register the births of their children. Although none of these assumptions are true, I mention them as they speak of the misunderstanding the general population has about plain people, who consider themselves to be in the world, but not of the world. As stated in Romans 12:2 “And be not conformed to this world: but be ye transformed by the renewing of your mind, that ye may prove what [is] that good, and acceptable, and perfect, will of God.” The world is considered a place to pass through, and while their salvation and subsequent entrance into heaven is not guaranteed, their strict adherence to biblical teachings, kindness, and unconditional acceptance of those who want to do right in the eyes of the Lord are something to be marveled at. They live a Bible-taught way of life as evidenced in every area of living: speech, dress, business, social purity, recreation, education, and non-participation in politics and warfare. They are strongly opposed to war, and are now given religious exemption from the United States’ military draft. They believe in the separation of church and state, nonconformity to the world, discipleship, and being born again by practicing adult baptism.

Some Mennonites refer to themselves as “The Quiet in the Land”, and it is a phrase I came across multiple times in the copious amounts of reading I did before approaching the church in Mount Pleasant. Quiet should not be taken literally, for their homes are often quite noisy—numerous children, friends, and neighbors often gather for meals—but the noise comes from the occupants rather than gadgets such as televisions and radios. In keeping with their lifestyle, it is believed that the television and radio spreads evil messages, and can therefore corrupt Christian beliefs. As such, children are found playing together, building things, or reading books. A favorite game is to play church! Those that are not old enough to read, or cannot read well, are always begging to have a story read to them. Story-telling is used for entertainment purposes as well as reinforcing biblical principles and practices, and there are many conservative Christian publishers that publish books especially for conservative Anabaptists, both for adults and children. These books often show characters in plain dress, in a rural setting, the sort of areas in which many plain communities live.

This quieter home experience, away from all the gadgets and modern 'smart' devices stands in stark contrast to the lives of many families today, who often use 'screen time' as a child minder, in an attempt to save two already overburdened parents the headache of having to entertain the children, having both spent the day at nine-to-five jobs. This all-too-real modern parental practice calls us to consider whether or not our current lifestyle is actually desirable, not to mention a practical approach, for our families. I had to ask myself, would our marriages last longer, our children be emotionally and physically healthier, and our lives be less materially focused if one parent were able to stay home?

My journey in meeting with, fellowshipping, and developing friendships in such a conservative Christian community has afforded me many opportunities to consider my current way of life, kindness and thoughtfulness towards others. Children are taught the acronym 'JOY', which stands for Jesus, Others, Yourself, and is the order in which they are taught to consider others. In contrast to these teachings, at the time of my first sermon in Mount Pleasant, I was single, without any dependents, and living with no family in the same country. I essentially had free rein on what I did with my time, my money, and my efforts. However, it was at a service about contentment that changed this for me. I distinctly remember being deeply touched by the idea of sacrifice, and how making small sacrifices would benefit others. After all, would we all really miss that twenty-dollar bill sitting in our wallets? Or would it be more beneficial to donate it to another cause? I couldn’t, honestly, even tell you what sum of money is in my wallet right now, which leads me to be believe that I wouldn’t miss it should it one day vanish.

[end of excerpt]

Cuprins

CONTENTS

Foreword by Herb Russell

Foreword by Liz Wells

Preface

Acknowledgments

Photographs

Bibliography

Endnotes

Foreword by Herb Russell

Foreword by Liz Wells

Preface

Acknowledgments

Photographs

Bibliography

Endnotes

Recenzii

“Flynn’s exquisite photos capture the simplicity and humility of Mennonite faith and life.”—Donald B. Kraybill, author of Concise Encyclopedia of Amish, Brethren, Hutterites, and Mennonites

“Informative and beautifully composed black white photos of a Mennonite community in southern and western Illinois. The images depict many characteristics of these particular Mennonite cultures, including plain church building exteriors and interiors, homes, plain clothing, farms and businesses, schools, family groupings, and more. The collection is significant for visualizing contemporary Mennonites and for future researchers.”—Steven D. Reschly, author of The Amish on the Iowa Prairie, 1840-1910, coeditor of Strangers at Home: Amish and Mennonite Women in History, and coauthor of Amish Women and the Great Depression

“Jane Flynn’s book of photographs and text is filled with compassion and insight reaped from her unique access to life among Southern Illinois’ Mennonites. Her Scottish roots are underpinned by an ancient history and her respectful, truthful documents of the ‘plain people’ show Flynn’s fascination with the traditions of another culture. Her careful diligence to show the truths about her experiences has created a book that sets a new bar for compassionate documentary.”—Daniel Overturf, photographer and coauthor of Illinois Trails and Traces: Portraits and Stories along the State’s Historic Routes

“An impressive compendium of captioned B/W photographs of Mennonites and two of their communities in Illinois, Jane Flynn's "Mennonites of Southern Illinois: A Photographic Journal" from the Southern Illinois University Press is extraordinary and unreservedly recommended for personal, professional, community, and college/university library American Photography collections and supplemental Mennonite curriculum studies lists.” —Midwest Book Review

“Informative and beautifully composed black white photos of a Mennonite community in southern and western Illinois. The images depict many characteristics of these particular Mennonite cultures, including plain church building exteriors and interiors, homes, plain clothing, farms and businesses, schools, family groupings, and more. The collection is significant for visualizing contemporary Mennonites and for future researchers.”—Steven D. Reschly, author of The Amish on the Iowa Prairie, 1840-1910, coeditor of Strangers at Home: Amish and Mennonite Women in History, and coauthor of Amish Women and the Great Depression

“Jane Flynn’s book of photographs and text is filled with compassion and insight reaped from her unique access to life among Southern Illinois’ Mennonites. Her Scottish roots are underpinned by an ancient history and her respectful, truthful documents of the ‘plain people’ show Flynn’s fascination with the traditions of another culture. Her careful diligence to show the truths about her experiences has created a book that sets a new bar for compassionate documentary.”—Daniel Overturf, photographer and coauthor of Illinois Trails and Traces: Portraits and Stories along the State’s Historic Routes

“An impressive compendium of captioned B/W photographs of Mennonites and two of their communities in Illinois, Jane Flynn's "Mennonites of Southern Illinois: A Photographic Journal" from the Southern Illinois University Press is extraordinary and unreservedly recommended for personal, professional, community, and college/university library American Photography collections and supplemental Mennonite curriculum studies lists.” —Midwest Book Review

Descriere

Offering a glimpse into a world largely misunderstood by mainstream society, this book documents the period of eight years that Jane Flynn practiced with Mennonites in two different Southern Illinois communities: Stonefort, and Mount Pleasant in Anna. The imagery explores the Mennonites’ labors, leisure, and faith by documenting their homes, places of work and worship, and the Illinois Ozark landscape they inhabit.