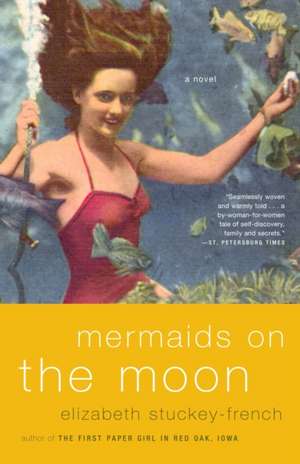

Mermaids on the Moon

Autor Elizabeth Stuckey-Frenchen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 iun 2003

Preț: 120.18 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 180

Preț estimativ în valută:

22.100€ • 24.01$ • 18.99£

22.100€ • 24.01$ • 18.99£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 25 martie-08 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780385498975

ISBN-10: 0385498977

Pagini: 272

Dimensiuni: 132 x 206 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

ISBN-10: 0385498977

Pagini: 272

Dimensiuni: 132 x 206 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

Notă biografică

Elizabeth Stuckey-French is the author of the short story collection The First Paper Girl in Red Oak, Iowa. Her stories have appeared in The Atlantic Monthly, Gettysburg Review, Southern Review, Five Points, and other literary journals. She lives in Tallahassee, Florida, where she teaches fiction writing at Florida State University.

Extras

One

The Fantasy Doll Theater had no telephone, so France drove out to tell Bruno about her mother's disappearance. The theater, where Bruno staged his Fantasy Doll shows, was thirty miles north of Indianapolis, on a county road a few miles from the town of Cedar Valley, up on a rise where the wind always blew. There was a magnificent view, but France was sure Bruno never noticed the rise and fall of the corn, rolling out for miles, the endless green grid broken up occasionally by a farmhouse glowing white under oak and maple trees. This morning, as usual, rain clouds filled the sky. France pulled up next to Bruno's van with the bashed-in side, a van he'd bought from a family who didn't have the insurance to fix it. She hated the sight of it.

When she got out of her Toyota she felt assaulted by sounds. A row of rocking chairs, with Bruno's wooden dolls propped up in them, rocked and squeaked in the wind. Other dolls spun around in a tin merry-go-round, ringing bells as they went. His theater and workshop were in what used to be an old general store. Big tin tubes--wind catchers--stuck up through the roof fantasy doll show--2 dollar admission read the hand-painted sign over the door.

Bruno began carving dolls soon after he and France started seeing each other again. A farmer mowing ditches near Bruno's house knocked down one of the cedar posts lining the county road, and Bruno'd helped himself to the post and crafted his first doll. He carved and painted a face, attached movable arms and legs made of pine, and after he finished, he announced that he'd found his calling. He figured out how to use wind power to make his dolls move and dance, sure they would draw a crowd.

Inside the dim, barnlike room, which smelled of mouse turds, was a little stage crowded with brightly dressed wooden dolls, and facing the stage were rows of chairs set up for the audience that never came. Bruno crouched on the stage among his dolls, wearing cutoffs and a tank shirt, oblivious, as usual, to the chill in the air. He'd played football at Indiana and had kept that build, even though he never exercised anymore. His golden brown hair was still thick and wavy. The lightly etched lines around his eyes looked as though he could wipe them away if he wanted to.

At the moment he was tying an ivory-colored bonnet under the chin of a doll wearing a ruffly, Little-House-on-the-Prairie dress. He dressed all the dolls in clothes he found at the thrift store, and he painted their lips and eyes and fingernails. They all had nameplates hanging like reading glasses from their necks. Wilma. Peanut. He didn't seem surprised to see France, even though he hadn't been expecting her until evening. It was her weekend to stay with him. "Francie Pants, meet Francie Pants," he said. Francie Pants was the first doll Bruno'd based on her, and she felt surprised and slightly offended by the doll's attire. "I can't decide," Bruno said, adjusting the doll's bonnet. "She sings, but should she play an instrument too? Maybe a fiddle."

"How about a washtub?" France suggested. She sat down on the edge of the stage, tucking her skirt around her legs. She'd never worn prairie clothes in her entire life. Right now she was dressed for work in a bright knit shirt and long black skirt, and when she left here they'd be covered in dust. "You forgot the corncob pipe," she told Bruno, trying to keep her tone light.

"Don't get prickly," said Bruno, grinning at her. "This here's the inner France. The one you try to hide. Your inner Pioneer."

"Whatever," France said. She'd rather he'd dressed it like a werewolf. "You've got three more dolls to make," she reminded him.

"One doll at a time. That's my motto."

Bruno was downwardly mobile. He lived in his parents' old frame house in Cedar Valley, which was stuffed with junk he'd collected and junk his parents had left behind when they retired to California, and he refused to either clean it up or move. He'd gone from managing three of his father's Mr. Donut restaurants to construction work to carving birdhouses and now dolls. If it weren't for France he wouldn't have even considered selling the dolls--he peddled firewood in the winter and produce in the summer for pocket money. But France knew she shouldn't nag him about making more dolls, or he'd dig his heels in. Besides, that wasn't why she'd come.

"Mom's gone," France said. "Nobody knows where she is."

Bruno was still fiddling with the new doll's bonnet. "Maybe she swam off with the real mermaids," he said. Unlike her father, Bruno didn't overtly make fun of her mother for donning a tail again at age sixty--could someone who dressed up dolls and put on Fantasy Doll shows cast any stones?--but he often referred to Grendy and her swimming partners as fake mermaids, contrasting them with the real ones who were out there somewhere.

Where had Grendy gone? Bruno's guess was as good as any. The only place she'd ever talked about going was back to Florida, and she got her wish three years ago, in 1997, when Mermaid Springs hosted a Mermaids of Yesteryear Reunion. All former mermaids were invited back to put on a special retrospective show. France and her father encouraged Grendy, who'd been a mermaid at Mermaid Springs from 1958-61, to attend the reunion. France's younger sister Beauvais had been dead for two years, and Grendy needed something to help her through the shock, so she grew her hair out, lost ten pounds, and went. The reunion was such a success that Mermaid Springs scheduled the older mermaids for regular performances. Earlier this year, in the spring of 2000, after North retired from the ministry of Cedar Valley Methodist Church, he and Grendy bought a second home in Mermaid City so she could participate in the Mermaids of Yesteryear shows. North acted like he thought the whole thing was ludicrous. "Why would people pay to watch fat old ladies swim?" he'd asked France, and, although she'd frowned at him, she'd wondered the same thing. Grendy refused to be offended. "Merhags, that's what we are," she said.

Over a hundred mermaids had come to the 1997 reunion, and quite a few wanted to swim in the first monthly shows, but after a while only a few diehards were left. The older mermaids weren't paid, just given free passes, and gradually most of them decided that it wasn't worth the trouble. Now there were only four left, and one of them was Grendy.

"Everything gets clear underwater," Grendy'd said, speaking to France from her home in Mermaid City. "I'm happier underwater than I've ever been on land. It's my salvation."

At first North had grumbled about hating Florida, but then he took a part-time job as an assistant pastor at Mermaid Springs Methodist and began playing golf again, and France, relieved, thought they were mellowing into their new life.

Then, this morning, she got her father's phone call from Florida. France lived in the Broad Ripple section of Indianapolis, in a large sunny studio apartment with unadorned white walls, furnished with a leather couch and armchair, a trunk doubling as a coffee table, a white iron bed, and a few other things she'd taken from the house she'd shared with her ex-husband, Ray. She had just finished the Star and was washing the coffeepot. She felt dread before she'd even said hello.

"I've got something to tell you," her father said, sounding almost gleeful. "Your mother's run off."

"You're lying." Her parents had been married for thirty-nine years.

"Hold on," he said. "Hold on. She left me a note that says she has to go find herself and she'll be in touch. She took the old Volvo."

"Find herself?" Her mother would never say that. "When's she coming back?"

"No idea. But there's no reason to be alarmed. She's a grown woman. She just got a bee in her bonnet."

"Why wouldn't I be alarmed?" France sat down at her kitchen table. "How could she leave without saying where she was going? And what about Theo?"

"It was a bit self-centered," he said piously, in his minister's voice. "She left Theo behind." Theo was Beauvais's six-year-old son. He had been strapped in his car seat, in the car with his mother, when a teenager in a Jeep veered over the center line and hit them head-on, killing Beauvais but leaving Theo unharmed. Beauvais had never revealed who Theo's father was, so North and Grendy took custody of him. France couldn't believe her mother had gone off and left him.

"Maybe something happened to her," France said. "Maybe she's been abducted."

"You've been watching too much TV," her father said. "Remember, she's done this before."

When France was eight and Beauvais six, Grendy disappeared for over a week. What France mostly remembered about that time was staying at the neighbors' house while her father went to Tucson to bring her mother back. The neighbors' house was dark and scary, with unfamiliar sour smells, small portions of food and strange rules--only one glass of milk per meal and lights out at seven-thirty. France and Beauvais slept in their sleeping bags in the living room, and as they lay wide awake in the twilight, Beauvais would tell her that their parents were never coming back, that they were now the Hunts' children and she'd better get used to it. After their mother returned there was never any discussion about her leaving, no explanation given. They all pretended it hadn't happened. But it had happened, and it was happening again. France, to her horror, was overwhelmed with the same fear and anxiety she'd felt back then.

Pressing the receiver too hard against her ear, she realized she was now outside, on the balcony of her apartment, watching a man try to start his Corvette in the parking lot. The engine stuttered and stuttered but wouldn't catch. She shivered. It was too cool for August. She could hear water still running in the kitchen. "Are you there?" she said into the phone.

Her father sighed. "I'm sorry."

"For what?"

"That this is so upsetting to you. How do you think it makes me feel? I'm the one who got left."

"I thought she was happy," France said. "I thought you were both happy."

"Join the club," said her father.

"Are you going to stay down in Mermaid City?"

"Oh no," he said. "Theo and I are coming back to Indiana ASAP. But the thing is, I can't take care of him by myself."

France felt the last piece of solid ground dissolving underneath her. "What are you saying?"

"I'm wondering if he could come stay in Indianapolis with you. Your mother's the one who took care of him. I'm too old to take care of a six-year-old."

"You're only sixty-six."

Her father lowered his voice. "He makes me nervous. There's something wrong with him."

"What? What's wrong with him?"

North laughed, a strangled little sound. "He's obsessive. He acts like a cat. He memorizes scientific facts and recites them at strange moments, but when you ask him a simple yes or no question, he can't answer. He avoids kids his own age. Can't get him to throw anything away. He has these terrible outbursts. I'm afraid he's mentally ill."

"Have you talked to a doctor?"

"Your mother won't admit there's a problem. But he's getting worse. I just can't handle him."

"What makes you think I can handle him?" France said, hating the whiny tone of her voice. She felt as if she were being sucked backward into a vortex. "Poor Theo," she said, to steady herself. She loved Theo, she did. He had seemed a bit strange when she saw him last Christmas at her parents' house in Cedar Valley. He paced back and forth, twiddling his fingers as he sang Christmas carols in his flat, toneless voice. She'd tried to talk to him, but his mind was somewhere else. "Don't you think he's gone through enough changes?" France asked her father. "He's probably freaked out about this."

"It would just be till your mother comes back."

"If she does," France said, and told her father she had to go.

Bruno hung a nameplate around his new doll's neck. Francie Pants had tons of freckles and irritatingly wholesome blue eyes. That thing is not me, France thought.

"Theo will love her," Bruno said.

She told Bruno about her father asking her to take Theo.

"Theo's a real treat," Bruno said. "Nothing wrong with Theo." Last Christmas, France had taken Theo to visit Bruno's studio, and he'd fit right in. He'd walked over to Wilma, the cowgirl doll, who was perched on a wooden rocking horse, and snatched the blond wig off her head, plopping it down on his own. He was exactly the same size as the dolls.

"Put that filthy wig back," France had said, but Bruno was laughing, so Theo'd ignored her. Later, Bruno and Theo went into town to get hamburgers, and, at Theo's suggestion, they put Wilma in the front passenger seat to ride along with them. Bruno never put the wig back on her, deciding he preferred her bald.

Bruno would be a terrible father, France had thought. He'd let a kid get away with anything. He wanted to marry France and have children, but marriage, France told him, was hard enough with no kids. Her first marriage had spooked her. She met Ray during her junior year at Purdue, when she was living in a sorority house and slowly losing her mind because of it. Ray, whose parents paid the rent for his off-campus apartment and the insurance premiums on his BMW, was halfheartedly working toward a degree in business administration. He spent all his money on clothes and all his spare time playing pool. He voted for Reagan. He and France had nothing in common, but they did not perceive this to be a problem. After they married they began to have violent arguments where they hurled things at each other. Sex got to be horribly self-conscious and somehow beside the point. They supplemented their own college furniture in the townhouse with office furniture Ray stole from whatever job he happened to have. France was relieved to be able, after five years, to leave it all behind, which she did when she got her first decent paying social work job and could afford to live on her own.

But the social work job also took a toll. It required her to investigate child abuse cases and to be a surrogate parent to abused and neglected foster kids for whom she could do next to nothing. She'd decided by then that she did not want children. Her own, or anybody else's. She wanted peace and quiet and order. But she also wanted Bruno, who was as resistant to changing his life as she was to changing hers.

From the Hardcover edition.

The Fantasy Doll Theater had no telephone, so France drove out to tell Bruno about her mother's disappearance. The theater, where Bruno staged his Fantasy Doll shows, was thirty miles north of Indianapolis, on a county road a few miles from the town of Cedar Valley, up on a rise where the wind always blew. There was a magnificent view, but France was sure Bruno never noticed the rise and fall of the corn, rolling out for miles, the endless green grid broken up occasionally by a farmhouse glowing white under oak and maple trees. This morning, as usual, rain clouds filled the sky. France pulled up next to Bruno's van with the bashed-in side, a van he'd bought from a family who didn't have the insurance to fix it. She hated the sight of it.

When she got out of her Toyota she felt assaulted by sounds. A row of rocking chairs, with Bruno's wooden dolls propped up in them, rocked and squeaked in the wind. Other dolls spun around in a tin merry-go-round, ringing bells as they went. His theater and workshop were in what used to be an old general store. Big tin tubes--wind catchers--stuck up through the roof fantasy doll show--2 dollar admission read the hand-painted sign over the door.

Bruno began carving dolls soon after he and France started seeing each other again. A farmer mowing ditches near Bruno's house knocked down one of the cedar posts lining the county road, and Bruno'd helped himself to the post and crafted his first doll. He carved and painted a face, attached movable arms and legs made of pine, and after he finished, he announced that he'd found his calling. He figured out how to use wind power to make his dolls move and dance, sure they would draw a crowd.

Inside the dim, barnlike room, which smelled of mouse turds, was a little stage crowded with brightly dressed wooden dolls, and facing the stage were rows of chairs set up for the audience that never came. Bruno crouched on the stage among his dolls, wearing cutoffs and a tank shirt, oblivious, as usual, to the chill in the air. He'd played football at Indiana and had kept that build, even though he never exercised anymore. His golden brown hair was still thick and wavy. The lightly etched lines around his eyes looked as though he could wipe them away if he wanted to.

At the moment he was tying an ivory-colored bonnet under the chin of a doll wearing a ruffly, Little-House-on-the-Prairie dress. He dressed all the dolls in clothes he found at the thrift store, and he painted their lips and eyes and fingernails. They all had nameplates hanging like reading glasses from their necks. Wilma. Peanut. He didn't seem surprised to see France, even though he hadn't been expecting her until evening. It was her weekend to stay with him. "Francie Pants, meet Francie Pants," he said. Francie Pants was the first doll Bruno'd based on her, and she felt surprised and slightly offended by the doll's attire. "I can't decide," Bruno said, adjusting the doll's bonnet. "She sings, but should she play an instrument too? Maybe a fiddle."

"How about a washtub?" France suggested. She sat down on the edge of the stage, tucking her skirt around her legs. She'd never worn prairie clothes in her entire life. Right now she was dressed for work in a bright knit shirt and long black skirt, and when she left here they'd be covered in dust. "You forgot the corncob pipe," she told Bruno, trying to keep her tone light.

"Don't get prickly," said Bruno, grinning at her. "This here's the inner France. The one you try to hide. Your inner Pioneer."

"Whatever," France said. She'd rather he'd dressed it like a werewolf. "You've got three more dolls to make," she reminded him.

"One doll at a time. That's my motto."

Bruno was downwardly mobile. He lived in his parents' old frame house in Cedar Valley, which was stuffed with junk he'd collected and junk his parents had left behind when they retired to California, and he refused to either clean it up or move. He'd gone from managing three of his father's Mr. Donut restaurants to construction work to carving birdhouses and now dolls. If it weren't for France he wouldn't have even considered selling the dolls--he peddled firewood in the winter and produce in the summer for pocket money. But France knew she shouldn't nag him about making more dolls, or he'd dig his heels in. Besides, that wasn't why she'd come.

"Mom's gone," France said. "Nobody knows where she is."

Bruno was still fiddling with the new doll's bonnet. "Maybe she swam off with the real mermaids," he said. Unlike her father, Bruno didn't overtly make fun of her mother for donning a tail again at age sixty--could someone who dressed up dolls and put on Fantasy Doll shows cast any stones?--but he often referred to Grendy and her swimming partners as fake mermaids, contrasting them with the real ones who were out there somewhere.

Where had Grendy gone? Bruno's guess was as good as any. The only place she'd ever talked about going was back to Florida, and she got her wish three years ago, in 1997, when Mermaid Springs hosted a Mermaids of Yesteryear Reunion. All former mermaids were invited back to put on a special retrospective show. France and her father encouraged Grendy, who'd been a mermaid at Mermaid Springs from 1958-61, to attend the reunion. France's younger sister Beauvais had been dead for two years, and Grendy needed something to help her through the shock, so she grew her hair out, lost ten pounds, and went. The reunion was such a success that Mermaid Springs scheduled the older mermaids for regular performances. Earlier this year, in the spring of 2000, after North retired from the ministry of Cedar Valley Methodist Church, he and Grendy bought a second home in Mermaid City so she could participate in the Mermaids of Yesteryear shows. North acted like he thought the whole thing was ludicrous. "Why would people pay to watch fat old ladies swim?" he'd asked France, and, although she'd frowned at him, she'd wondered the same thing. Grendy refused to be offended. "Merhags, that's what we are," she said.

Over a hundred mermaids had come to the 1997 reunion, and quite a few wanted to swim in the first monthly shows, but after a while only a few diehards were left. The older mermaids weren't paid, just given free passes, and gradually most of them decided that it wasn't worth the trouble. Now there were only four left, and one of them was Grendy.

"Everything gets clear underwater," Grendy'd said, speaking to France from her home in Mermaid City. "I'm happier underwater than I've ever been on land. It's my salvation."

At first North had grumbled about hating Florida, but then he took a part-time job as an assistant pastor at Mermaid Springs Methodist and began playing golf again, and France, relieved, thought they were mellowing into their new life.

Then, this morning, she got her father's phone call from Florida. France lived in the Broad Ripple section of Indianapolis, in a large sunny studio apartment with unadorned white walls, furnished with a leather couch and armchair, a trunk doubling as a coffee table, a white iron bed, and a few other things she'd taken from the house she'd shared with her ex-husband, Ray. She had just finished the Star and was washing the coffeepot. She felt dread before she'd even said hello.

"I've got something to tell you," her father said, sounding almost gleeful. "Your mother's run off."

"You're lying." Her parents had been married for thirty-nine years.

"Hold on," he said. "Hold on. She left me a note that says she has to go find herself and she'll be in touch. She took the old Volvo."

"Find herself?" Her mother would never say that. "When's she coming back?"

"No idea. But there's no reason to be alarmed. She's a grown woman. She just got a bee in her bonnet."

"Why wouldn't I be alarmed?" France sat down at her kitchen table. "How could she leave without saying where she was going? And what about Theo?"

"It was a bit self-centered," he said piously, in his minister's voice. "She left Theo behind." Theo was Beauvais's six-year-old son. He had been strapped in his car seat, in the car with his mother, when a teenager in a Jeep veered over the center line and hit them head-on, killing Beauvais but leaving Theo unharmed. Beauvais had never revealed who Theo's father was, so North and Grendy took custody of him. France couldn't believe her mother had gone off and left him.

"Maybe something happened to her," France said. "Maybe she's been abducted."

"You've been watching too much TV," her father said. "Remember, she's done this before."

When France was eight and Beauvais six, Grendy disappeared for over a week. What France mostly remembered about that time was staying at the neighbors' house while her father went to Tucson to bring her mother back. The neighbors' house was dark and scary, with unfamiliar sour smells, small portions of food and strange rules--only one glass of milk per meal and lights out at seven-thirty. France and Beauvais slept in their sleeping bags in the living room, and as they lay wide awake in the twilight, Beauvais would tell her that their parents were never coming back, that they were now the Hunts' children and she'd better get used to it. After their mother returned there was never any discussion about her leaving, no explanation given. They all pretended it hadn't happened. But it had happened, and it was happening again. France, to her horror, was overwhelmed with the same fear and anxiety she'd felt back then.

Pressing the receiver too hard against her ear, she realized she was now outside, on the balcony of her apartment, watching a man try to start his Corvette in the parking lot. The engine stuttered and stuttered but wouldn't catch. She shivered. It was too cool for August. She could hear water still running in the kitchen. "Are you there?" she said into the phone.

Her father sighed. "I'm sorry."

"For what?"

"That this is so upsetting to you. How do you think it makes me feel? I'm the one who got left."

"I thought she was happy," France said. "I thought you were both happy."

"Join the club," said her father.

"Are you going to stay down in Mermaid City?"

"Oh no," he said. "Theo and I are coming back to Indiana ASAP. But the thing is, I can't take care of him by myself."

France felt the last piece of solid ground dissolving underneath her. "What are you saying?"

"I'm wondering if he could come stay in Indianapolis with you. Your mother's the one who took care of him. I'm too old to take care of a six-year-old."

"You're only sixty-six."

Her father lowered his voice. "He makes me nervous. There's something wrong with him."

"What? What's wrong with him?"

North laughed, a strangled little sound. "He's obsessive. He acts like a cat. He memorizes scientific facts and recites them at strange moments, but when you ask him a simple yes or no question, he can't answer. He avoids kids his own age. Can't get him to throw anything away. He has these terrible outbursts. I'm afraid he's mentally ill."

"Have you talked to a doctor?"

"Your mother won't admit there's a problem. But he's getting worse. I just can't handle him."

"What makes you think I can handle him?" France said, hating the whiny tone of her voice. She felt as if she were being sucked backward into a vortex. "Poor Theo," she said, to steady herself. She loved Theo, she did. He had seemed a bit strange when she saw him last Christmas at her parents' house in Cedar Valley. He paced back and forth, twiddling his fingers as he sang Christmas carols in his flat, toneless voice. She'd tried to talk to him, but his mind was somewhere else. "Don't you think he's gone through enough changes?" France asked her father. "He's probably freaked out about this."

"It would just be till your mother comes back."

"If she does," France said, and told her father she had to go.

Bruno hung a nameplate around his new doll's neck. Francie Pants had tons of freckles and irritatingly wholesome blue eyes. That thing is not me, France thought.

"Theo will love her," Bruno said.

She told Bruno about her father asking her to take Theo.

"Theo's a real treat," Bruno said. "Nothing wrong with Theo." Last Christmas, France had taken Theo to visit Bruno's studio, and he'd fit right in. He'd walked over to Wilma, the cowgirl doll, who was perched on a wooden rocking horse, and snatched the blond wig off her head, plopping it down on his own. He was exactly the same size as the dolls.

"Put that filthy wig back," France had said, but Bruno was laughing, so Theo'd ignored her. Later, Bruno and Theo went into town to get hamburgers, and, at Theo's suggestion, they put Wilma in the front passenger seat to ride along with them. Bruno never put the wig back on her, deciding he preferred her bald.

Bruno would be a terrible father, France had thought. He'd let a kid get away with anything. He wanted to marry France and have children, but marriage, France told him, was hard enough with no kids. Her first marriage had spooked her. She met Ray during her junior year at Purdue, when she was living in a sorority house and slowly losing her mind because of it. Ray, whose parents paid the rent for his off-campus apartment and the insurance premiums on his BMW, was halfheartedly working toward a degree in business administration. He spent all his money on clothes and all his spare time playing pool. He voted for Reagan. He and France had nothing in common, but they did not perceive this to be a problem. After they married they began to have violent arguments where they hurled things at each other. Sex got to be horribly self-conscious and somehow beside the point. They supplemented their own college furniture in the townhouse with office furniture Ray stole from whatever job he happened to have. France was relieved to be able, after five years, to leave it all behind, which she did when she got her first decent paying social work job and could afford to live on her own.

But the social work job also took a toll. It required her to investigate child abuse cases and to be a surrogate parent to abused and neglected foster kids for whom she could do next to nothing. She'd decided by then that she did not want children. Her own, or anybody else's. She wanted peace and quiet and order. But she also wanted Bruno, who was as resistant to changing his life as she was to changing hers.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Seamlessly woven and warmly told . . . a by-woman-for-women tale of self-discovery, family and secrets.” —St. Petersburg Times

“Stuckey-French . . . has a deep sensibility for the intimate dramas of unheralded lives played out on the miniscule stages of supermarkets, family restaurants and trailer parks.” —The Miami Herald

“Hilarious and wacky, this story displays a variety of family loves and disappointments in a quirky, original way.” —Elizabeth Strout, author of Amy and Isabelle

“Funny and witty, filled with enough quirky characters to open its own amusement park.”—San Francisco Chronicle

“A lot of fun. . . . Creates a believable world of women aging not with resigned grace but with feisty zest.” —The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

“Stuckey-French . . . has a deep sensibility for the intimate dramas of unheralded lives played out on the miniscule stages of supermarkets, family restaurants and trailer parks.” —The Miami Herald

“Hilarious and wacky, this story displays a variety of family loves and disappointments in a quirky, original way.” —Elizabeth Strout, author of Amy and Isabelle

“Funny and witty, filled with enough quirky characters to open its own amusement park.”—San Francisco Chronicle

“A lot of fun. . . . Creates a believable world of women aging not with resigned grace but with feisty zest.” —The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

Descriere

From the author of "The First Paper Girl in Red Oak, Iowa" comes a witty, whimsical, and refreshingly offbeat novel about the mysterious disappearance of an aging mermaid.