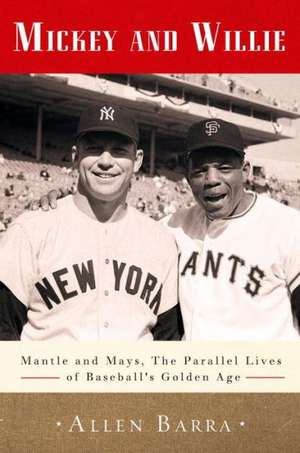

Mickey and Willie: Mantle and Mays, the Parallel Lives of Baseball's Golden Age

Autor Allen Barraen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mar 2014

Culturally, Mickey Mantle and Willie Mays were light-years apart. Yet they were nearly the same age and almost the same size, and they came to New York at the same time. They possessed virtually the same talents and played the same position. They were both products of generations of baseball-playing families, for whom the game was the only escape from a lifetime of brutal manual labor. Both were nearly crushed by the weight of the outsized expectations placed on them, first by their families and later by America. Both lived secret lives far different from those their fans knew. What their fans also didn't know was that the two men shared a close personal friendship--and that each was the only man who could truly understand the other's experience.

Preț: 141.03 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 212

Preț estimativ în valută:

26.99€ • 28.07$ • 22.28£

26.99€ • 28.07$ • 22.28£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 24 martie-07 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307716491

ISBN-10: 030771649X

Pagini: 479

Ilustrații: 3 8-PAGE INSERTS

Dimensiuni: 130 x 203 x 33 mm

Greutate: 0.43 kg

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

ISBN-10: 030771649X

Pagini: 479

Ilustrații: 3 8-PAGE INSERTS

Dimensiuni: 130 x 203 x 33 mm

Greutate: 0.43 kg

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

Notă biografică

ALLEN BARRA is the author of Inventing Wyatt Earp, The Last Coach, and Yogi Berra, as well as several essay collections. He is a regular contributor to such publications as the Wall Street Journal, Daily Beast, and Salon.

Extras

1

Fathers and Sons

If a scientific research team were to conduct an exhaustive study of the ideal places, times, and conditions for breeding the perfect baseball player, they’d surely come up with something very close to Westfield, Alabama, in the heart of Birmingham’s steel industry, or the mining district of Commerce, Oklahoma.

Thousands of southern blacks left their homes during the Depression and moved to industrial cities in the North, but in Westfield, Alabama, William Howard “Cat” Mays chose to stay home. Grueling as the work in the local steel mills was, Cat understood that the promise of a better life in towns like Gary, Indiana, Flint, Michigan, and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, was remote. He stayed in Alabama. At the same time, countless families from Oklahoma and adjoining states made the decision to abandon everything and make the hazardous trek to California; their stories would be told in prose by John Steinbeck and in song by Woody Guthrie. No one spoke for Elvin Charles “Mutt” Mantle, who chose to keep his family in Oklahoma, taking jobs as a road grader, tenant farmer, and, finally, miner to put food on the table.

For both Cat Mays and Mutt Mantle, the main recreation—practically the only one—was baseball, specifically the industrial league baseball organized by their companies. They raised their boys in a baseball culture. No fathers ever guided their sons toward professional baseball with more single-mindedness than Cat and Mutt. Both men saw baseball as a way to get their sons out of those small towns, out of the mills and mines, although they guided them in very different ways. And once Mickey and Willie left, neither ever lived in his hometown again.

Willie Howard Mays—why he was not named William like his father has never been explained—was born in Westfield on May 6, 1931. There’s no monument or plaque to mark the spot; little of the Westfield that Willie knew remains standing today. A pamphlet printed by the Birmingham Chamber of Commerce in the 1960s called it a “village,” which is inaccurate—Westfield was never a village or a town, but a community of neighborhoods populated by black working-class families whose lifeline was the steel mills in nearby Fairfield. Virtually all the houses were of the type called “shotgun”—it was said that you could fire a shotgun at the front door and the pellets would go out the back door. They were built and owned by mills such as the Tennessee Cast Iron and Railroad Company (TCI), the great subcorporation of U.S. Steel, officially to “benefit” the workers but in reality to maintain their dependence on their employers.

The larger town of Fairfield provided necessary services—such as schools—to the small nearby communities like Westfield. Fairfield was born in 1910, the same year that nearby Rickwood Field opened, and it was a planned community from the start, the result of U.S. Steel’s purchase of TCI.

Years later in his autobiography, Jackie Robinson, criticizing Willie for his lack of involvement in the civil rights movement, would remind Mays of his roots: “I hope Willie hasn’t forgotten his shotgun house in Birmingham slums, wind-whistling through its clapboards, as he sits in his $85,000 mansion in San Francisco’s fashionable Forest Hills, or the concentration camp atmosphere of the Shacktown of his boyhood.” 1

The house Willie grew up in was fairly standard for families of black steelworkers, and not terribly unlike those of most white steelworkers in the Birmingham area. In fact, it was not a great deal different from the house of a zinc miner in Commerce, Oklahoma, where Mickey Mantle grew up. Some might have rated the Mays home as superior: an early Mays biography describes the house he grew up in as “middle class.” 2 It’s doubtful anyone would have said that to describe the Mantles’ house in Commerce; Cat’s family had little money, but his house had electricity, which the Mantle home did not.

Today some of the neighborhoods in and around Westfield are in ruin. All that’s left of most of the original company houses is their foundations. The population has been shrinking steadily for decades, from perhaps 5,000 when Willie was born to just over 1,100 in 1990 and under 1,000 today. The steel industry that sustained these communities began deserting the Birmingham area in the late 1970s, and the industrial baseball leagues that produced Willie Mays were gone at least two decades before that.

The black population of Alabama yielded many fine baseball players, among them perhaps the game’s greatest pitcher, Satchel Paige; the leading home run hitter of the twentieth century, Henry Aaron; and arguably the greatest all-around player in the game’s history, Willie Mays. The greatest concentration of black baseball talent in the country was in the South, and in the South no state produced as many Negro League players as Alabama; in Alabama the preponderance of talent came from the industrial leagues of the Birmingham area.

Mays grew up in a baseball tradition that was more than half a century old when he was born. Baseball had been introduced to the Deep South after 1865 by Confederate soldiers who had learned the game either from their Union captors in prison camps or during breaks when men from the two armies would get together for some R&R before they resumed slaughtering one another. How the game came to be popular with southern blacks is a subject on which historians are split. Some say that free blacks learned it from their former masters. Others suggest that black soldiers in the Union Army, who numbered perhaps 200,000, picked it up from their white comrades. Yet a third possibility is that blacks watched white men play, then went home and played it themselves. It’s likely that all three factors had a role.

The father of black ball in Alabama was a man named Charles Isam Taylor, who went to Birmingham from South Carolina in 1904. A veteran of the U.S. Army and the Spanish-American War, Taylor worked his way through Clark College in Atlanta, where he helped organize the school’s first baseball team. For four years, Taylor made a living by staging and promoting (and sometimes playing in) baseball games for Birmingham’s black fans. In 1910, realizing that there was more money to be made above the Mason-Dixon Line (where black teams could be matched against white teams), Taylor moved his team to the industrial town of West Baden, Indiana. The fans were heartbroken, and at least one black newspaper, the Birmingham Reporter, continued to print items about their games, passing on information about the local lads who were playing ball so far from home. From there, Taylor fades into obscurity, but his brainchild of using the industrial leagues as a talent farm for a professional league lived on and flourished.

If there was one progressive aspect to the steel and coal barons who dominated Birmingham industry, it was that they saw the value of sponsoring baseball teams among the black as well as the white workforces. Baseball provided great exercise and improved morale enormously, and shirts with company names and logos proved to be cheap but effective advertising.

Lorenzo “Piper” Davis, the most important figure in Birmingham black ball history, was Willie Mays’s mentor and first manager. He told me in 1987, “There is a lot to be said about the way the companies treated us. It was the closest thing a black man could get to a square deal. They paid for bats and gloves and uniforms, and they even paid for our travel expenses to go play other company teams.” 3

Davis, of course, was speaking of a time in the late 1930s and early 1940s when the Birmingham steel industry, shaking off the Depression, was booming again, but from the years before World War I until the early 1950s, when a combination of factors ranging from the civil rights struggle to televised major league baseball eroded support for both the Negro Leagues and white minor leagues, Birmingham could lay claim to being the baseball capital of the South.

Allen Harvey Woodward, known to his friends for reasons no one can remember as “Rick,” was one of the big reasons. Rick was the son of steel baron Joseph Hersey Woodward and, despite his father’s indifference, was an enthusiastic supporter of Woodward Iron’s company team. In 1909 he made a daring move—supervising the construction of the first steel-and-concrete ballpark in the South. Rickwood Field, named in a radio contest and combining the owner’s nickname with the first part of his last name, became the home of a team called the Birmingham Barons, named for the coal and steel magnates who ran Birmingham. It would also be home, beginning in the early 1920s, to the Black Barons, who played on alternate Sundays and other days when the white team was traveling.

Rickwood Field opened on August 18, 1910. It was largely modeled after Shibe Park in Philadelphia, home of Connie Mack’s champion A’s—Mack himself came to Birmingham to advise Woodward on construction details—while also incorporating elements of Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field and Cincinnati’s Crosley Field (still known in 1910 as “Palace of the Fans”), ballparks that Willie Mays would still be performing in more than half a century later. Rickwood, which stands today as the oldest ballpark in the country, was for decades the crown jewel of southern baseball. It was as if history wanted to provide Willie Mays with a worthy stage from which to launch his legend.

Willie Mays would become the favorite ballplayer of New York’s liberal-leaning sportswriters, but there was a conservative streak in him that the writers never acknowledged. He came by it naturally enough. His father was named for William Howard Taft, who was president in 1912, the year Cat was born. Many blacks in Alabama, like blacks throughout the South, supported the racially progressive Republican Party of Abraham Lincoln, Teddy Roosevelt, and William Howard Taft. When the party turned more conservative, they continued to support it if only because most of the local political machines were controlled by white Democrats.

Birmingham after World War II would become one of the hotbeds of black civil rights activism, particularly when black GIs returned from the war. But there were pockets of the black population outside the city who did not easily understand or quickly respond to the call for civil rights. Willie Mays was raised in such neighborhoods, first in Westfield and then later a few miles away in Fairfield. When Willie was born, most black families in Westfield and the surrounding areas didn’t have roots there. They had come there for jobs in the mills and foundries, which had sprung up only in the late 1890s. Black mine and mill workers came to enjoy a certain autonomy and created a life for themselves less dehumanizing than was possible in much of Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and even South Alabama, where there weren’t many opportunities for blacks other than picking cotton, lumber sharecropping, and truck farming.

Because of the steel and coal industry, most of the black communities to the south and west of Birmingham were more or less self-sufficient and in most ways independent of the city. They had schools, churches, restaurants, and even movie theaters that were black-owned and -operated (though the movie houses got the films only after they had run in the white theaters). On Saturday afternoons, when there was a nickel to spare, young Willie would see the B-movie Westerns he loved so much and get to fantasize that he too would someday be a cowboy like Hoot Gibson, Gene Autry, Roy Rogers, or Johnny Mack Brown, who had been a football star at the Univer-sity of Alabama in the mid-1920s and became a national celebrity when the Crimson Tide won the 1926 Rose Bowl. At the same time, Mickey Mantle sat in all-white theaters in Commerce, Oklahoma, thrilling to the same celluloid cowboys, including Oklahoma’s own Tom Mix.

Willie’s father Cat—or sometimes “Kitty Cat” (or “Kat” with a “K” in early writings on Willie)—was, in the words of Charles Einstein, “a small bouncy, Buddha-tummied figure.” 4 His nickname came from his reflexes—his teammates always admired the way he broke immediately in the right direction on fly balls—and the way he sprang out of the batter’s box on bunts. William Howard Mays learned his baseball from his father, Walter, who had been a sharecropper in Tuscaloosa and was a pretty fair country pitcher. “It went from him through me,” said Cat, “and to the third generation, my own son. And they say the third generation is it.” 5

During Willie’s formative years, Cat worked in the “spike and bolt” shop of TCI and starred for its company team, just one of several organized teams he played for before and after the war. “I’d play for anybody who’d give you money,” he told Charles Einstein, “because every time somebody came to get me to play baseball, I’d say, ‘I can’t go, man—I got something to do,’ and he’d say, ‘Come on, man, I’ll give you $2.50.’ Sometimes when things was bad, you’d have to go for ten cent [sic] a game. And for that money you learned baseball. You know, I used to study the pitchers when I got on first base ’cause I could bunt my way on, and if I got on first base it was like getting a double. And to me, from second base to third base was much easier than from first to second.” 6

Sometime in 1930, Cat, maybe while picking up some spending money on a traveling ball team, met Annie Satterwhite. Annie was sixteen when Willie was born, but she and Cat never married. Her mother had been dead for several years, and sometime before that her father had abandoned the family. Not much is known about Annie, and Willie talked little about her in his adult years. Shortly after his birth, he was given over to the women he would call his aunts, his mother’s younger sisters: Sarah, thirteen, and Ernestine—or “Steen,” as Willie called her—just nine.

Or at least that’s the story Willie told numerous writers. The truth may be a great deal stranger. Willie never addressed the question of why his mother, who settled down near Westfield after she married a man named Frank McMorris, never brought him to live with her. Moreover, the true identities of Ernestine and Sarah have never been established. In the earliest books on Willie, the girls are said to be Annie’s younger sisters, as they are in James Hirsch’s massive 2010 biography: “As a baby, he was given to his mother’s two younger sisters, 13-year-old Sarah and 9-year-old Ernestine, who were his principal caretakers and who called him ‘Junior.’ ” Sarah was “the most important female figure in the boy’s life, a role she played even after Willie left Alabama to play for the Giants.” The makeshift family, writes Hirsch, “expanded to include two more children born out of wedlock, one from Sarah and one from Ernestine. Both women later married, Sarah to Cat’s cousin, Edgar May, who at some point lost the ‘s’ on his last name (or perhaps Cat Mays’s family added the ‘s’). Sarah May ended up raising her sister’s son while married to his father’s cousin.” 7

Fathers and Sons

If a scientific research team were to conduct an exhaustive study of the ideal places, times, and conditions for breeding the perfect baseball player, they’d surely come up with something very close to Westfield, Alabama, in the heart of Birmingham’s steel industry, or the mining district of Commerce, Oklahoma.

Thousands of southern blacks left their homes during the Depression and moved to industrial cities in the North, but in Westfield, Alabama, William Howard “Cat” Mays chose to stay home. Grueling as the work in the local steel mills was, Cat understood that the promise of a better life in towns like Gary, Indiana, Flint, Michigan, and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, was remote. He stayed in Alabama. At the same time, countless families from Oklahoma and adjoining states made the decision to abandon everything and make the hazardous trek to California; their stories would be told in prose by John Steinbeck and in song by Woody Guthrie. No one spoke for Elvin Charles “Mutt” Mantle, who chose to keep his family in Oklahoma, taking jobs as a road grader, tenant farmer, and, finally, miner to put food on the table.

For both Cat Mays and Mutt Mantle, the main recreation—practically the only one—was baseball, specifically the industrial league baseball organized by their companies. They raised their boys in a baseball culture. No fathers ever guided their sons toward professional baseball with more single-mindedness than Cat and Mutt. Both men saw baseball as a way to get their sons out of those small towns, out of the mills and mines, although they guided them in very different ways. And once Mickey and Willie left, neither ever lived in his hometown again.

Willie Howard Mays—why he was not named William like his father has never been explained—was born in Westfield on May 6, 1931. There’s no monument or plaque to mark the spot; little of the Westfield that Willie knew remains standing today. A pamphlet printed by the Birmingham Chamber of Commerce in the 1960s called it a “village,” which is inaccurate—Westfield was never a village or a town, but a community of neighborhoods populated by black working-class families whose lifeline was the steel mills in nearby Fairfield. Virtually all the houses were of the type called “shotgun”—it was said that you could fire a shotgun at the front door and the pellets would go out the back door. They were built and owned by mills such as the Tennessee Cast Iron and Railroad Company (TCI), the great subcorporation of U.S. Steel, officially to “benefit” the workers but in reality to maintain their dependence on their employers.

The larger town of Fairfield provided necessary services—such as schools—to the small nearby communities like Westfield. Fairfield was born in 1910, the same year that nearby Rickwood Field opened, and it was a planned community from the start, the result of U.S. Steel’s purchase of TCI.

Years later in his autobiography, Jackie Robinson, criticizing Willie for his lack of involvement in the civil rights movement, would remind Mays of his roots: “I hope Willie hasn’t forgotten his shotgun house in Birmingham slums, wind-whistling through its clapboards, as he sits in his $85,000 mansion in San Francisco’s fashionable Forest Hills, or the concentration camp atmosphere of the Shacktown of his boyhood.” 1

The house Willie grew up in was fairly standard for families of black steelworkers, and not terribly unlike those of most white steelworkers in the Birmingham area. In fact, it was not a great deal different from the house of a zinc miner in Commerce, Oklahoma, where Mickey Mantle grew up. Some might have rated the Mays home as superior: an early Mays biography describes the house he grew up in as “middle class.” 2 It’s doubtful anyone would have said that to describe the Mantles’ house in Commerce; Cat’s family had little money, but his house had electricity, which the Mantle home did not.

Today some of the neighborhoods in and around Westfield are in ruin. All that’s left of most of the original company houses is their foundations. The population has been shrinking steadily for decades, from perhaps 5,000 when Willie was born to just over 1,100 in 1990 and under 1,000 today. The steel industry that sustained these communities began deserting the Birmingham area in the late 1970s, and the industrial baseball leagues that produced Willie Mays were gone at least two decades before that.

The black population of Alabama yielded many fine baseball players, among them perhaps the game’s greatest pitcher, Satchel Paige; the leading home run hitter of the twentieth century, Henry Aaron; and arguably the greatest all-around player in the game’s history, Willie Mays. The greatest concentration of black baseball talent in the country was in the South, and in the South no state produced as many Negro League players as Alabama; in Alabama the preponderance of talent came from the industrial leagues of the Birmingham area.

Mays grew up in a baseball tradition that was more than half a century old when he was born. Baseball had been introduced to the Deep South after 1865 by Confederate soldiers who had learned the game either from their Union captors in prison camps or during breaks when men from the two armies would get together for some R&R before they resumed slaughtering one another. How the game came to be popular with southern blacks is a subject on which historians are split. Some say that free blacks learned it from their former masters. Others suggest that black soldiers in the Union Army, who numbered perhaps 200,000, picked it up from their white comrades. Yet a third possibility is that blacks watched white men play, then went home and played it themselves. It’s likely that all three factors had a role.

The father of black ball in Alabama was a man named Charles Isam Taylor, who went to Birmingham from South Carolina in 1904. A veteran of the U.S. Army and the Spanish-American War, Taylor worked his way through Clark College in Atlanta, where he helped organize the school’s first baseball team. For four years, Taylor made a living by staging and promoting (and sometimes playing in) baseball games for Birmingham’s black fans. In 1910, realizing that there was more money to be made above the Mason-Dixon Line (where black teams could be matched against white teams), Taylor moved his team to the industrial town of West Baden, Indiana. The fans were heartbroken, and at least one black newspaper, the Birmingham Reporter, continued to print items about their games, passing on information about the local lads who were playing ball so far from home. From there, Taylor fades into obscurity, but his brainchild of using the industrial leagues as a talent farm for a professional league lived on and flourished.

If there was one progressive aspect to the steel and coal barons who dominated Birmingham industry, it was that they saw the value of sponsoring baseball teams among the black as well as the white workforces. Baseball provided great exercise and improved morale enormously, and shirts with company names and logos proved to be cheap but effective advertising.

Lorenzo “Piper” Davis, the most important figure in Birmingham black ball history, was Willie Mays’s mentor and first manager. He told me in 1987, “There is a lot to be said about the way the companies treated us. It was the closest thing a black man could get to a square deal. They paid for bats and gloves and uniforms, and they even paid for our travel expenses to go play other company teams.” 3

Davis, of course, was speaking of a time in the late 1930s and early 1940s when the Birmingham steel industry, shaking off the Depression, was booming again, but from the years before World War I until the early 1950s, when a combination of factors ranging from the civil rights struggle to televised major league baseball eroded support for both the Negro Leagues and white minor leagues, Birmingham could lay claim to being the baseball capital of the South.

Allen Harvey Woodward, known to his friends for reasons no one can remember as “Rick,” was one of the big reasons. Rick was the son of steel baron Joseph Hersey Woodward and, despite his father’s indifference, was an enthusiastic supporter of Woodward Iron’s company team. In 1909 he made a daring move—supervising the construction of the first steel-and-concrete ballpark in the South. Rickwood Field, named in a radio contest and combining the owner’s nickname with the first part of his last name, became the home of a team called the Birmingham Barons, named for the coal and steel magnates who ran Birmingham. It would also be home, beginning in the early 1920s, to the Black Barons, who played on alternate Sundays and other days when the white team was traveling.

Rickwood Field opened on August 18, 1910. It was largely modeled after Shibe Park in Philadelphia, home of Connie Mack’s champion A’s—Mack himself came to Birmingham to advise Woodward on construction details—while also incorporating elements of Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field and Cincinnati’s Crosley Field (still known in 1910 as “Palace of the Fans”), ballparks that Willie Mays would still be performing in more than half a century later. Rickwood, which stands today as the oldest ballpark in the country, was for decades the crown jewel of southern baseball. It was as if history wanted to provide Willie Mays with a worthy stage from which to launch his legend.

Willie Mays would become the favorite ballplayer of New York’s liberal-leaning sportswriters, but there was a conservative streak in him that the writers never acknowledged. He came by it naturally enough. His father was named for William Howard Taft, who was president in 1912, the year Cat was born. Many blacks in Alabama, like blacks throughout the South, supported the racially progressive Republican Party of Abraham Lincoln, Teddy Roosevelt, and William Howard Taft. When the party turned more conservative, they continued to support it if only because most of the local political machines were controlled by white Democrats.

Birmingham after World War II would become one of the hotbeds of black civil rights activism, particularly when black GIs returned from the war. But there were pockets of the black population outside the city who did not easily understand or quickly respond to the call for civil rights. Willie Mays was raised in such neighborhoods, first in Westfield and then later a few miles away in Fairfield. When Willie was born, most black families in Westfield and the surrounding areas didn’t have roots there. They had come there for jobs in the mills and foundries, which had sprung up only in the late 1890s. Black mine and mill workers came to enjoy a certain autonomy and created a life for themselves less dehumanizing than was possible in much of Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and even South Alabama, where there weren’t many opportunities for blacks other than picking cotton, lumber sharecropping, and truck farming.

Because of the steel and coal industry, most of the black communities to the south and west of Birmingham were more or less self-sufficient and in most ways independent of the city. They had schools, churches, restaurants, and even movie theaters that were black-owned and -operated (though the movie houses got the films only after they had run in the white theaters). On Saturday afternoons, when there was a nickel to spare, young Willie would see the B-movie Westerns he loved so much and get to fantasize that he too would someday be a cowboy like Hoot Gibson, Gene Autry, Roy Rogers, or Johnny Mack Brown, who had been a football star at the Univer-sity of Alabama in the mid-1920s and became a national celebrity when the Crimson Tide won the 1926 Rose Bowl. At the same time, Mickey Mantle sat in all-white theaters in Commerce, Oklahoma, thrilling to the same celluloid cowboys, including Oklahoma’s own Tom Mix.

Willie’s father Cat—or sometimes “Kitty Cat” (or “Kat” with a “K” in early writings on Willie)—was, in the words of Charles Einstein, “a small bouncy, Buddha-tummied figure.” 4 His nickname came from his reflexes—his teammates always admired the way he broke immediately in the right direction on fly balls—and the way he sprang out of the batter’s box on bunts. William Howard Mays learned his baseball from his father, Walter, who had been a sharecropper in Tuscaloosa and was a pretty fair country pitcher. “It went from him through me,” said Cat, “and to the third generation, my own son. And they say the third generation is it.” 5

During Willie’s formative years, Cat worked in the “spike and bolt” shop of TCI and starred for its company team, just one of several organized teams he played for before and after the war. “I’d play for anybody who’d give you money,” he told Charles Einstein, “because every time somebody came to get me to play baseball, I’d say, ‘I can’t go, man—I got something to do,’ and he’d say, ‘Come on, man, I’ll give you $2.50.’ Sometimes when things was bad, you’d have to go for ten cent [sic] a game. And for that money you learned baseball. You know, I used to study the pitchers when I got on first base ’cause I could bunt my way on, and if I got on first base it was like getting a double. And to me, from second base to third base was much easier than from first to second.” 6

Sometime in 1930, Cat, maybe while picking up some spending money on a traveling ball team, met Annie Satterwhite. Annie was sixteen when Willie was born, but she and Cat never married. Her mother had been dead for several years, and sometime before that her father had abandoned the family. Not much is known about Annie, and Willie talked little about her in his adult years. Shortly after his birth, he was given over to the women he would call his aunts, his mother’s younger sisters: Sarah, thirteen, and Ernestine—or “Steen,” as Willie called her—just nine.

Or at least that’s the story Willie told numerous writers. The truth may be a great deal stranger. Willie never addressed the question of why his mother, who settled down near Westfield after she married a man named Frank McMorris, never brought him to live with her. Moreover, the true identities of Ernestine and Sarah have never been established. In the earliest books on Willie, the girls are said to be Annie’s younger sisters, as they are in James Hirsch’s massive 2010 biography: “As a baby, he was given to his mother’s two younger sisters, 13-year-old Sarah and 9-year-old Ernestine, who were his principal caretakers and who called him ‘Junior.’ ” Sarah was “the most important female figure in the boy’s life, a role she played even after Willie left Alabama to play for the Giants.” The makeshift family, writes Hirsch, “expanded to include two more children born out of wedlock, one from Sarah and one from Ernestine. Both women later married, Sarah to Cat’s cousin, Edgar May, who at some point lost the ‘s’ on his last name (or perhaps Cat Mays’s family added the ‘s’). Sarah May ended up raising her sister’s son while married to his father’s cousin.” 7