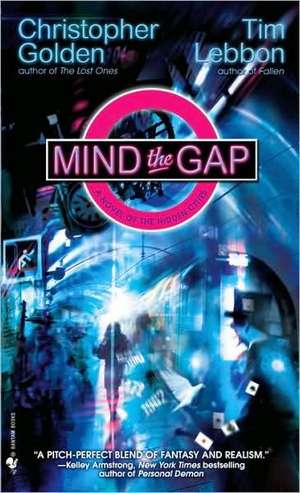

Mind the Gap: A Novel of the Hidden Cities

Autor Christopher Golden, Tim Lebbonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 dec 2034

falling through one of the cracks in the world.…

Two of today’s brightest stars of dark fantasy combine their award-winning, critically acclaimed talents in this spellbinding new tale of magic, terror, and adventure that begins when a young woman slips through the space between our everyday world and the one hiding just beneath it.

Always assume there’s someone after you. That was the paranoid wisdom her mother had hardwired into Jasmine Towne ever since she was a little girl. Now, suddenly on her own, Jazz is going to need every skill she has ever been taught to survive enemies both seen and unseen. For her mother had given Jazz one last invaluable piece of advice, written in her own blood.

Jazz Hide Forever

All her life Jazz has known them only as the “Uncles,” and her mother seemed to fear them as much as depend on them. Now these enigmatic, black-clad strangers are after Jazz for reasons she can’t fathom, and her only escape is to slip into the forgotten tunnels of London’s vast underground. Here she will meet a tribe of survivors calling themselves the United Kingdom and begin an adventure that links her to the ghosts of a city long past, a father she never knew, and a destiny she fears only slightly less than the relentless killers who’d commit any crime under heaven or earth to prevent her from fulfilling it.

From the Trade Paperback edition.

Preț: 46.45 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 70

Preț estimativ în valută:

8.89€ • 9.66$ • 7.47£

8.89€ • 9.66$ • 7.47£

Carte nepublicată încă

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780553590067

ISBN-10: 0553590065

Pagini: 384

Greutate: 0.19 kg

Editura: Random House Publishing Group

Colecția Spectra

ISBN-10: 0553590065

Pagini: 384

Greutate: 0.19 kg

Editura: Random House Publishing Group

Colecția Spectra

Recenzii

“A pitch-perfect blend of fantasy and realism. Golden and Lebbon craft a riveting tale of adventure that is both gritty and magical.” —Kelley Armstrong, author of Personal Demon

"Magical realism at its finest…. with mystery, magic, ghosts and a fascinating subterranean world.”—Sfrevu.com

“A dark urban fantasy that posits a world of multiple Londons, some real and some ghostly, an ancient legacy of magic, and a secret war between those who seek power to control it and those who seek to free it.”—Library Journal, starred review

“Super-fast pacing and creepy touches.”—Publishers Weekly

"Magical realism at its finest…. with mystery, magic, ghosts and a fascinating subterranean world.”—Sfrevu.com

“A dark urban fantasy that posits a world of multiple Londons, some real and some ghostly, an ancient legacy of magic, and a secret war between those who seek power to control it and those who seek to free it.”—Library Journal, starred review

“Super-fast pacing and creepy touches.”—Publishers Weekly

Notă biografică

Christopher Golden’s novels include The Lost Ones, The Myth Hunters, Wildwood Road, The Boys are Back in Town, The Ferryman, Strangewood, Of Saints and Shadows, and The Borderkind. Golden co-wrote the lavishly illustrated novel Baltimore, or, The Steadfast The Steadfast Tin Soldier and The Vampire, with Mike Mignola, and they are currently scripting it as a feature film for the New Regency. He has also written books for teens and young adults, including the thriller series Body of Evidence, honored by the New York Public Library and chosen as one of YALSA’s Best Books for Young Readers. Upcoming teen novels include Poison Ink for Delacorte, Soulless for MTV Books, and The Secret Journeys of Jack London, a collaboration with Tim Lebbon. With Thomas E. Sniegoski, he is the co-author of the dark fantasy series The Menagerie as well as the young readers fantasy series OutCast and the comic book miniseries Talent, both of which were recently acquired by Universal Pictures. Golden and Sniegoski also wrote the upcoming comic book miniseries The Sisterhood, currently in development as a feature film. Golden was born and raised in Massachusetts, where he still lives with his family. At present he is collaborating with Tim Lebbon on The Map of Moments, the second novel of The Hidden Cities.

Tim Lebbon has won two British Fantasy awards, a Bram Stoker award, and a Tombstone award, and has been a finalist for International Horror Guild and World Fantasy awards. Several of his novels and novellas are currently under option in the USA and the UK. He lives in South Wales with his wife and two children.

Tim Lebbon has won two British Fantasy awards, a Bram Stoker award, and a Tombstone award, and has been a finalist for International Horror Guild and World Fantasy awards. Several of his novels and novellas are currently under option in the USA and the UK. He lives in South Wales with his wife and two children.

Extras

Chapter One

little birds

Even before she saw the house, Jazz knew that something was wrong. She could smell it in the air, see it in the shifting shadows of the trees lining the street, hear it in the expectant silence. She could feel it in her bones.

Dread gave her pause, and for a moment she stood and listened to the stillness. She wanted to run, but she told herself not to be hasty, that her mother had long since hardwired her for paranoia and so her instincts should be trusted.

She hurried along a narrow, overgrown alleyway that emerged into a lane behind the row of terraced town houses. Not many people came this way, out beyond the gardens, and she was confident that she could move closer to home without being seen.

But seen by whom?

Her mother's voice rang through her head: Always assume there's someone after you until you prove there isn't. Maybe everyone had that cautionary voice in the back of their mind; their conscience, their Jiminy Cricket. For Jazz, it always sounded like her mother.

She walked along the path, carefully and slowly, avoiding piles of dog shit and the glistening shards of used needles. Every thirty seconds she paused and listened. The dreadful silence had passed and the sounds of normalcy seemed to fill the air again. Mothers shouted at misbehaving children, babies hollered, doors slammed, dogs barked, and TVs blared inanely into the spaces between. She let out a breath she hadn't been aware of holding. Maybe the heat and grime of the city had gotten to her more than usual today.

Trust your instincts, her mother would say.

"Yeah, right." Jazz crept along until she reached her home's back gate, then paused to take stock once more. The normal sounds and smells were still there, but, beyond the gate, the weighted silence remained. The windows were dark and the air felt thick, the way it did before a storm. It was as if her house was surrounded by a bubble of stillness, and that in itself was disquieting. Perhaps she's just asleep, Jazz thought. But, more unnerved than ever, she knew she should take no chances.

She backed along the alley for a dozen steps and waited outside her neighbor's gate. She peered through a knothole in the wood, scoping the garden. The house seemed to be silent and abandoned, but not in the same ominous fashion as her own. Birds still sang in this garden. She knew that Mr. Barker lived alone, that he went to work early and returned late every day. So unless his cleaners were in, his house would be deserted.

"Good," Jazz whispered. "It'll turn out to be nothing, but . . ." But at least it'll relieve the boredom. To and from school, day in, day out, few real friends, and her mother constantly on edge even though the Uncles made sure they never had any financial worries. No worries at all, the Uncles always said. . . .

Yeah, it'd turn out to be nothing, but better to be careful. If she ever told her mother she'd had some kind of dreadful intuition, even in the slightest, and had ignored it, the woman would be furious. Her mother trusted no one, and even though Jazz couldn't help but follow her in those beliefs, still she sometimes hated it. She wanted a life. She wanted friends.

She opened Mr. Barker's gate. The wall between their gardens was too high to see over, and from the back of his garden she could see only two upstairs windows in her house—her own bedroom window and the bathroom next to it. She looked up for a few seconds, then brashly walked the length of the garden to Barker's back door.

Nobody shouted, nobody came after her. The neighborhood noise continued. But to her left, over the wall, that deathly silence persisted.

Something is wrong, she thought.

Mr. Barker's back door was sensibly locked. Jazz closed her eyes and turned the handle a couple of times, gauging the pressure and resistance. She nodded in satisfaction; she should be able to pick it.

Taking a small pocketknife from her jeans, she opened the finest blade, slipped it into the lock, and felt around.

A bird called close by, startling her. She glanced up at the wall and saw a robin sitting on its top, barely ten feet away. Its head jerked this way and that, and it sang again.

Above the robin, past the wall, a shape was leaning from Jazz's bedroom window.

She froze. It was difficult to make out any details, silhouetted as the shape was against the sky, but when it turned, she saw the outline of a ponytail, the sharp corner of a shirt collar.

It was the Uncle who told her to call him Mort.

She never bothered with their names. To her they were just the Uncles, the name her mother had been using ever since Jazz could remember. They came to visit regularly, sometimes in pairs or threes, sometimes on their own. They would ask her mother how things were, whether she needed anything or if she'd "had any thoughts." They never accepted a drink or the offer of food, but they always left behind an envelope containing a sheaf of used ten- and twenty-pound notes.

They told Jazz that she never had to worry about anything, which only worried her more. When they left, her mother would slide the envelope into a drawer as though it was dirty.

But what was this one doing in her bedroom? Whatever his purpose, Jazz didn't like it. They had never, ever come into her room when she was at home, and her mother assured her that they did not snoop around when she was out. They were perfect gentlemen. Like gangsters, Jazz had said once, and we're their molls. Her mother had smiled but did not respond.

The Uncle turned his head, scanning the gardens and alleyway.

He'll see me. If the robin calls again and he looks down to locate it, he'll see me pressed here against Mr. Barker's back door.

The bird hopped along the head of the wall, pausing to peck at an insect or two. Jazz worked at the lock without looking, waiting for the feel of the tumblers snicking into place. One . . . two . . . three . . . two to go, and the last two were always the hardest.

The Uncle moved to withdraw back into the room, and Jazz let go of her breath in a sigh of relief.

The robin chirped, singing along with the chaotic London buzz of traffic and shouts.

The Uncle leaned from the window again just as Jazz felt the lock disengage. She turned the handle and pushed her way in behind the opening door, never looking away from the shadow of the man at her bedroom window.

He didn't see me, she thought. She left the door open; he'd be more likely to see the movement of it closing than to notice it was open.

The robin fluttered away.

Jazz did not wait to question what was happening, or why. She hurried through Mr. Barker's house, careful not to knock into any furniture, cautious as she opened or closed doors. She didn't want to make the slightest sound.

In his living room, she moved to the front window. The wooden Venetian blinds were closed, but, pressing her face to the wall, she could see past their edge. Out in the street, she saw just what she had feared.

Two large black cars were parked outside her house. Beamers.

Jazz's heart was thumping, her skin tingling. Something's happened. Rarely had more than three Uncles visited at once, and now there were two cars here, parked prominently in the street with windows still open and engines running, as if daring anyone to approach. They're a law unto themselves, her mother sometimes said.

Her mum had rarely said anything outright against the Uncles, but she never needed to. Her unease was there on her face for her daughter to see. But Jazz could not just sit here and spy on her own house, wondering what had gone wrong.

She and her mum had talked many times about fleeing the house if trouble ever came to the door. They'd made plans, created a virtual map in their minds, and once or twice they'd pursued the escape route, just to make sure it could really work.

All Jazz had to do now was reverse it.

She found Mr. Barker's attic hatch in one of his back bedrooms. This was a cold, sterile room with white walls, bare timber floors, and only an old rattan chair as furniture. She lifted the chair instead of dragging it, positioning it beneath the hatch, then stood carefully on its arms and pushed the hatch open. It tipped to the side and thumped onto the timber joists.

Jazz cringed and held her breath. It had been a soft impact, muffled in the attic. Unlikely it would travel through to her house; these places were solid.

Got to be more careful than that.

Fingers gripping the edge of the square hole in the ceiling, she pushed off the chair, trying to get her elbows over the lip of the hatch. The chair rocked, tipping onto two legs and then back again with another soft thud. She let her torso and legs dangle there for a while, preparing to haul herself up and in. Jazz was fitter than most girls her age—others were more interested in boys, drinking, and sex than in keeping themselves fit and healthy—but she also knew that she could easily hurt herself. One torn muscle and . . .

And what? I won't be able to run? She couldn't shake the sense of foreboding. The sun shone outside, a beautiful summer afternoon. But gray winter seemed to be closing in.

She lifted herself up into the darkness, sitting on the hatch's edge and resting for a moment. Listening. Looking for light from elsewhere. She still had no idea what had happened. If the Uncles were waiting for her to come home, perhaps they'd also be checking her house. And that could mean the attic too.

When her eyes had become accustomed to the darkness, she set off on hands and knees. Mr. Barker's attic had floorboards, so the going was relatively easy. The old bachelor didn't have much stuff to store, it seemed; there were a couple of taped-up boxes tucked into one corner and an open box of books slowly swelling with damp. Mustiness permeated the attic, and she wondered why he'd shoved the box up here. She hadn't seen a bookcase anywhere downstairs. There were rumors that Mr. Barker's wife had left him ten years ago, so perhaps these books held too many ghosts for him to live with.

At the wall dividing Barker's property from hers, Jazz crawled into the narrowing gap between floor and sloping roof. Right at the eaves, just where her mother said it would be, was a gap where a dozen blocks had been removed. Lazy builders, she'd said when Jazz had asked. But Jazz found it easy to imagine her mother up here with a chisel and hammer, while she was in school and Mr. Barker was at work.

She wriggled through the hole into her own attic. There were no floorboards here, and she had to move carefully from joist to joist. One slip and her foot or knee would break through the plasterboard ceiling into the house below. She guessed she was right above her bedroom.

A wooden beam creaked beneath her and she froze, cursing her clumsiness. She should have listened first, tried to figure out whether the Uncle was still in there. Too late now. She lowered her head, turned so that her ear pressed against the itching fiber-wool insulation, and held her breath.

Voices. Two men were talking, but she could barely hear their mumbled tones. She was pretty sure their voices did not come from directly below. Her room, she thought, was empty—for now.

There were two hatches that led down from the attic into the town house. One was above the landing, visible to anyone in the upstairs corridor or anyone looking up the stairs from below. And then there was the second, just to her right, which her mother had installed in Jazz's bedroom. Emergency escape, she'd said, smiling, when Jazz had asked what she was doing.

Everything you told me was right, Jazz thought. She felt tears threatening but couldn't go to that place yet. Not here, and not now.

She crawled to the hatch, feeling her way through the darkness. When she touched its bare wood and felt the handle, she paused for a minute, listening. She could still hear muffled voices, but they seemed to come from farther away than her bedroom.

Jazz closed her eyes and concentrated. Sometimes she could sense whether someone else was close. Most people called it a sixth sense, though usually it was a combination of the other five. With her, sometimes, it was different.

She frowned, opened her eyes, and grasped the handle.

Maybe there was an Uncle standing directly below her. Maybe not. There was only one way to find out.

Jazz lifted the hatch quickly and squinted against the sudden light. She leaned over the hole and found her room empty.

Good start, she thought. Everything her mother had said to her, everything she had been taught, shouted at her to flee. But there was something going on here that she had to understand before she could bring herself to run.

Jazz lowered herself from the hatch into her room, landing lightly on the tips of her toes, knees bending to absorb the impact. She remained in that pose, looking around her room and listening for movement from outside.

Her drawers had been opened, her bookcase upset, and clothes were strewn across the floor. The cover of her journal lay loose and torn on her bed like a gutted bird.

Mum! she thought. And for the first time, the fear came in hard. The Uncles had always protected and helped them, even if her mother had little respect for them. But now they seemed dangerous. It was as if their surface veneer had been stripped away and her perception of them was becoming clear at last.

She glanced back up at the ceiling hatch, close enough to her desk that it would be easy to jump up and disappear again.

The voices startled her. There were two of them, seeming to come from directly outside her door. She slid beside her bed and lay there listening, expecting Mort to enter her room at any second. He would not see her straightaway, but he would see the open hatch. And then they'd have her.

"We could be waiting here forever," one voice said. Mort.

"We won't. She'll be home soon." This other voice was female.

little birds

Even before she saw the house, Jazz knew that something was wrong. She could smell it in the air, see it in the shifting shadows of the trees lining the street, hear it in the expectant silence. She could feel it in her bones.

Dread gave her pause, and for a moment she stood and listened to the stillness. She wanted to run, but she told herself not to be hasty, that her mother had long since hardwired her for paranoia and so her instincts should be trusted.

She hurried along a narrow, overgrown alleyway that emerged into a lane behind the row of terraced town houses. Not many people came this way, out beyond the gardens, and she was confident that she could move closer to home without being seen.

But seen by whom?

Her mother's voice rang through her head: Always assume there's someone after you until you prove there isn't. Maybe everyone had that cautionary voice in the back of their mind; their conscience, their Jiminy Cricket. For Jazz, it always sounded like her mother.

She walked along the path, carefully and slowly, avoiding piles of dog shit and the glistening shards of used needles. Every thirty seconds she paused and listened. The dreadful silence had passed and the sounds of normalcy seemed to fill the air again. Mothers shouted at misbehaving children, babies hollered, doors slammed, dogs barked, and TVs blared inanely into the spaces between. She let out a breath she hadn't been aware of holding. Maybe the heat and grime of the city had gotten to her more than usual today.

Trust your instincts, her mother would say.

"Yeah, right." Jazz crept along until she reached her home's back gate, then paused to take stock once more. The normal sounds and smells were still there, but, beyond the gate, the weighted silence remained. The windows were dark and the air felt thick, the way it did before a storm. It was as if her house was surrounded by a bubble of stillness, and that in itself was disquieting. Perhaps she's just asleep, Jazz thought. But, more unnerved than ever, she knew she should take no chances.

She backed along the alley for a dozen steps and waited outside her neighbor's gate. She peered through a knothole in the wood, scoping the garden. The house seemed to be silent and abandoned, but not in the same ominous fashion as her own. Birds still sang in this garden. She knew that Mr. Barker lived alone, that he went to work early and returned late every day. So unless his cleaners were in, his house would be deserted.

"Good," Jazz whispered. "It'll turn out to be nothing, but . . ." But at least it'll relieve the boredom. To and from school, day in, day out, few real friends, and her mother constantly on edge even though the Uncles made sure they never had any financial worries. No worries at all, the Uncles always said. . . .

Yeah, it'd turn out to be nothing, but better to be careful. If she ever told her mother she'd had some kind of dreadful intuition, even in the slightest, and had ignored it, the woman would be furious. Her mother trusted no one, and even though Jazz couldn't help but follow her in those beliefs, still she sometimes hated it. She wanted a life. She wanted friends.

She opened Mr. Barker's gate. The wall between their gardens was too high to see over, and from the back of his garden she could see only two upstairs windows in her house—her own bedroom window and the bathroom next to it. She looked up for a few seconds, then brashly walked the length of the garden to Barker's back door.

Nobody shouted, nobody came after her. The neighborhood noise continued. But to her left, over the wall, that deathly silence persisted.

Something is wrong, she thought.

Mr. Barker's back door was sensibly locked. Jazz closed her eyes and turned the handle a couple of times, gauging the pressure and resistance. She nodded in satisfaction; she should be able to pick it.

Taking a small pocketknife from her jeans, she opened the finest blade, slipped it into the lock, and felt around.

A bird called close by, startling her. She glanced up at the wall and saw a robin sitting on its top, barely ten feet away. Its head jerked this way and that, and it sang again.

Above the robin, past the wall, a shape was leaning from Jazz's bedroom window.

She froze. It was difficult to make out any details, silhouetted as the shape was against the sky, but when it turned, she saw the outline of a ponytail, the sharp corner of a shirt collar.

It was the Uncle who told her to call him Mort.

She never bothered with their names. To her they were just the Uncles, the name her mother had been using ever since Jazz could remember. They came to visit regularly, sometimes in pairs or threes, sometimes on their own. They would ask her mother how things were, whether she needed anything or if she'd "had any thoughts." They never accepted a drink or the offer of food, but they always left behind an envelope containing a sheaf of used ten- and twenty-pound notes.

They told Jazz that she never had to worry about anything, which only worried her more. When they left, her mother would slide the envelope into a drawer as though it was dirty.

But what was this one doing in her bedroom? Whatever his purpose, Jazz didn't like it. They had never, ever come into her room when she was at home, and her mother assured her that they did not snoop around when she was out. They were perfect gentlemen. Like gangsters, Jazz had said once, and we're their molls. Her mother had smiled but did not respond.

The Uncle turned his head, scanning the gardens and alleyway.

He'll see me. If the robin calls again and he looks down to locate it, he'll see me pressed here against Mr. Barker's back door.

The bird hopped along the head of the wall, pausing to peck at an insect or two. Jazz worked at the lock without looking, waiting for the feel of the tumblers snicking into place. One . . . two . . . three . . . two to go, and the last two were always the hardest.

The Uncle moved to withdraw back into the room, and Jazz let go of her breath in a sigh of relief.

The robin chirped, singing along with the chaotic London buzz of traffic and shouts.

The Uncle leaned from the window again just as Jazz felt the lock disengage. She turned the handle and pushed her way in behind the opening door, never looking away from the shadow of the man at her bedroom window.

He didn't see me, she thought. She left the door open; he'd be more likely to see the movement of it closing than to notice it was open.

The robin fluttered away.

Jazz did not wait to question what was happening, or why. She hurried through Mr. Barker's house, careful not to knock into any furniture, cautious as she opened or closed doors. She didn't want to make the slightest sound.

In his living room, she moved to the front window. The wooden Venetian blinds were closed, but, pressing her face to the wall, she could see past their edge. Out in the street, she saw just what she had feared.

Two large black cars were parked outside her house. Beamers.

Jazz's heart was thumping, her skin tingling. Something's happened. Rarely had more than three Uncles visited at once, and now there were two cars here, parked prominently in the street with windows still open and engines running, as if daring anyone to approach. They're a law unto themselves, her mother sometimes said.

Her mum had rarely said anything outright against the Uncles, but she never needed to. Her unease was there on her face for her daughter to see. But Jazz could not just sit here and spy on her own house, wondering what had gone wrong.

She and her mum had talked many times about fleeing the house if trouble ever came to the door. They'd made plans, created a virtual map in their minds, and once or twice they'd pursued the escape route, just to make sure it could really work.

All Jazz had to do now was reverse it.

She found Mr. Barker's attic hatch in one of his back bedrooms. This was a cold, sterile room with white walls, bare timber floors, and only an old rattan chair as furniture. She lifted the chair instead of dragging it, positioning it beneath the hatch, then stood carefully on its arms and pushed the hatch open. It tipped to the side and thumped onto the timber joists.

Jazz cringed and held her breath. It had been a soft impact, muffled in the attic. Unlikely it would travel through to her house; these places were solid.

Got to be more careful than that.

Fingers gripping the edge of the square hole in the ceiling, she pushed off the chair, trying to get her elbows over the lip of the hatch. The chair rocked, tipping onto two legs and then back again with another soft thud. She let her torso and legs dangle there for a while, preparing to haul herself up and in. Jazz was fitter than most girls her age—others were more interested in boys, drinking, and sex than in keeping themselves fit and healthy—but she also knew that she could easily hurt herself. One torn muscle and . . .

And what? I won't be able to run? She couldn't shake the sense of foreboding. The sun shone outside, a beautiful summer afternoon. But gray winter seemed to be closing in.

She lifted herself up into the darkness, sitting on the hatch's edge and resting for a moment. Listening. Looking for light from elsewhere. She still had no idea what had happened. If the Uncles were waiting for her to come home, perhaps they'd also be checking her house. And that could mean the attic too.

When her eyes had become accustomed to the darkness, she set off on hands and knees. Mr. Barker's attic had floorboards, so the going was relatively easy. The old bachelor didn't have much stuff to store, it seemed; there were a couple of taped-up boxes tucked into one corner and an open box of books slowly swelling with damp. Mustiness permeated the attic, and she wondered why he'd shoved the box up here. She hadn't seen a bookcase anywhere downstairs. There were rumors that Mr. Barker's wife had left him ten years ago, so perhaps these books held too many ghosts for him to live with.

At the wall dividing Barker's property from hers, Jazz crawled into the narrowing gap between floor and sloping roof. Right at the eaves, just where her mother said it would be, was a gap where a dozen blocks had been removed. Lazy builders, she'd said when Jazz had asked. But Jazz found it easy to imagine her mother up here with a chisel and hammer, while she was in school and Mr. Barker was at work.

She wriggled through the hole into her own attic. There were no floorboards here, and she had to move carefully from joist to joist. One slip and her foot or knee would break through the plasterboard ceiling into the house below. She guessed she was right above her bedroom.

A wooden beam creaked beneath her and she froze, cursing her clumsiness. She should have listened first, tried to figure out whether the Uncle was still in there. Too late now. She lowered her head, turned so that her ear pressed against the itching fiber-wool insulation, and held her breath.

Voices. Two men were talking, but she could barely hear their mumbled tones. She was pretty sure their voices did not come from directly below. Her room, she thought, was empty—for now.

There were two hatches that led down from the attic into the town house. One was above the landing, visible to anyone in the upstairs corridor or anyone looking up the stairs from below. And then there was the second, just to her right, which her mother had installed in Jazz's bedroom. Emergency escape, she'd said, smiling, when Jazz had asked what she was doing.

Everything you told me was right, Jazz thought. She felt tears threatening but couldn't go to that place yet. Not here, and not now.

She crawled to the hatch, feeling her way through the darkness. When she touched its bare wood and felt the handle, she paused for a minute, listening. She could still hear muffled voices, but they seemed to come from farther away than her bedroom.

Jazz closed her eyes and concentrated. Sometimes she could sense whether someone else was close. Most people called it a sixth sense, though usually it was a combination of the other five. With her, sometimes, it was different.

She frowned, opened her eyes, and grasped the handle.

Maybe there was an Uncle standing directly below her. Maybe not. There was only one way to find out.

Jazz lifted the hatch quickly and squinted against the sudden light. She leaned over the hole and found her room empty.

Good start, she thought. Everything her mother had said to her, everything she had been taught, shouted at her to flee. But there was something going on here that she had to understand before she could bring herself to run.

Jazz lowered herself from the hatch into her room, landing lightly on the tips of her toes, knees bending to absorb the impact. She remained in that pose, looking around her room and listening for movement from outside.

Her drawers had been opened, her bookcase upset, and clothes were strewn across the floor. The cover of her journal lay loose and torn on her bed like a gutted bird.

Mum! she thought. And for the first time, the fear came in hard. The Uncles had always protected and helped them, even if her mother had little respect for them. But now they seemed dangerous. It was as if their surface veneer had been stripped away and her perception of them was becoming clear at last.

She glanced back up at the ceiling hatch, close enough to her desk that it would be easy to jump up and disappear again.

The voices startled her. There were two of them, seeming to come from directly outside her door. She slid beside her bed and lay there listening, expecting Mort to enter her room at any second. He would not see her straightaway, but he would see the open hatch. And then they'd have her.

"We could be waiting here forever," one voice said. Mort.

"We won't. She'll be home soon." This other voice was female.