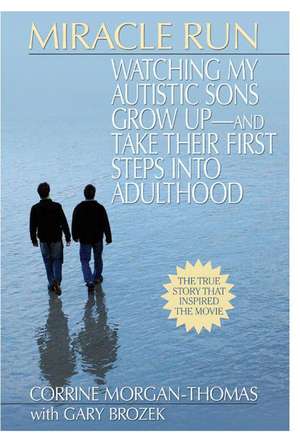

Miracle Run: Watching My Autistic Sons Grow Up - and Take Their First Steps Into Adulthood

Autor Corrine Morgan-Thomas Gary Brozeken Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 ian 2009 – vârsta de la 18 ani

The inspiration for the Lifetime movie and a guide for parents confronting their autistic children's journeys to adulthood.

Parents of autistic children often wonder: What will happen to our kids when they grow up? Can they work? Have relationships and their own families? Here is the poignant story of one woman watching her autistic boys reach adulthood.

A single mother barely making ends meet, Corrine Morgan-Thomas could hardly afford doctors for her twins, Stephen and Phillip. After their diagnosis of autism, no one else thought these boys would ever amount to anything. But Corrine managed single-handedly to keep the boys out of institutions-and in "regular" school. And their inspiring story became Lifetime television's Miracle Run.

The real miracle, though, was what happened where the movie left off-when Stephen and Phillip graduated to face adult autism. From their diagnosis to the present day, when the boys have grown into young men leading happy lives, Corrine's eye-opening story is full of candor, humor, and most of all, hope.

Parents of autistic children often wonder: What will happen to our kids when they grow up? Can they work? Have relationships and their own families? Here is the poignant story of one woman watching her autistic boys reach adulthood.

A single mother barely making ends meet, Corrine Morgan-Thomas could hardly afford doctors for her twins, Stephen and Phillip. After their diagnosis of autism, no one else thought these boys would ever amount to anything. But Corrine managed single-handedly to keep the boys out of institutions-and in "regular" school. And their inspiring story became Lifetime television's Miracle Run.

The real miracle, though, was what happened where the movie left off-when Stephen and Phillip graduated to face adult autism. From their diagnosis to the present day, when the boys have grown into young men leading happy lives, Corrine's eye-opening story is full of candor, humor, and most of all, hope.

Preț: 132.03 lei

Preț vechi: 138.98 lei

-5% Nou

Puncte Express: 198

Preț estimativ în valută:

25.26€ • 27.02$ • 21.06£

25.26€ • 27.02$ • 21.06£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 27 martie-10 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780425225820

ISBN-10: 0425225828

Pagini: 325

Dimensiuni: 140 x 208 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.39 kg

Editura: Berkley Publishing Group

ISBN-10: 0425225828

Pagini: 325

Dimensiuni: 140 x 208 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.39 kg

Editura: Berkley Publishing Group

Extras

In any teen’s life, two rites of passage stand out: first love and getting a driver’s license. As complicated as both those matters can be, when you factor autism into the equation, you have to have a mastery of higher math and a grasp of the chemistry of the volatile emotions of teenagers firmly in your mind.

Although I had mixed feelings about them falling in love, I firmly believed that Stephen and Phillip had the right to apply for and to try to get their driver’s licenses. If they passed the written and the driving tests, demonstrating the competency that any other citizen possessed, then why not?

On the other hand, I had some pretty good why- nots in mind. The anxiety level they both exhibited in new situations, especially when exposed to things like loud noises, would potentially make them a danger to themselves and to other drivers. All the medications that Phillip was on and the unpredictable interactions among those drugs didn’t make him a good candidate for driving. When I stacked those reasons up against their strong desire to drive, and what more potent symbol of a teen’s freedom and independence exists than driving, I was torn. I didn’t want to be the one to stand in the way of their dream being fulfilled. To give you a better idea of how much driving meant to him, Phillip had written a song aptly titled “The DMV Song.” I didn’t like to ever play favorites, but I could reasonably imagine Stephen being able to earn his license. With Phillip, I thought the odds were stacked against him.

On one occasion, I took them both to the DMV office. I turned them loose after telling them which line to stand in. I sat in a waiting area with my fingers crossed, hoping that they’d both fail the written test. I knew that would greatly disappoint them both, but failing on their own was better than me not allowing them to do something they wanted so badly to do. The first time Phillip took the written test, I could see that he was struggling. I don’t know if it was nerves or what, but I could read the panic in his eyes as he scanned the questions.

That surprised me since they had both studied very hard for the test. When Phillip completed his test and brought it to the clerk, he kind of shuffled up and looked as though he was about to collapse with in himself. It took a few moments for him to get his score, and when he was called back up, it was clear that he hadn’t passed. I breathed a deep sigh of relief. Stephen had already passed the written portion of the exam and was in line to take the vision test. I now only had one to worry about.

Then I noticed that the clerk had taken Phillip aside. I didn’t want to make a scene, so I stood up and inched my way closer to where the pair was standing. The clerk, obviously very sympathetic to Phillip’s plight, was asking him a series of really basic questions about driving. The next thing I knew, he was shaking Phillip’s hand and congratulating him for passing the written test. I couldn’t believe it. It was a nice gesture, but all I could think of was that he was hoping that Phillip wouldn’t make it past some of the other hurdles he had yet to face.

As it turned out, neither of the boys passed the driving portion of the exam. I was so relieved. They both vowed to work harder and to pass the next time. As bad as I felt rooting against my sons, I knew that in the end their not getting to drive was a good thing. I would hate for them to do harm to themselves and to another driver or pedestrian. Balancing what is right for them with the needs of the larger community is an ongoing task.

I believe that someday they will both be able to drive. Quite a few high- functioning autistics do, and I feel that once the twins mature a little more and learn to deal better with loud noises and such, they will be good drivers. One thing is for sure: they would never get lost. Stephen especially is like a human Global Positioning Satellite. I’m not fond of driving, and I frequently get lost, but if Stephen or Phillip is in the car with me, I never have to worry about finding my way. It is uncanny how we can be traveling in some unfamiliar place and they always manage to get me back on the road to home.

The twins still talk about getting their licenses, and I think that one day they will. They just have to be patient, a virtue whose importance we all became acutely aware of throughout the years.

As for that other major adolescent rite of passage— first love— I knew I wouldn’t be able to have the proverbial birds and the bees discussion with Stephen and Phillip. I knew that my nervousness and awkward attempts to communicate with them about reproduction and sexual intimacy would send the wrong signal to them. If I stuttered and stammered, hemmed and hawed, turned beet red and blanched at any of their questions I thought were too frank, all I would do was add to their confusion. I also knew that I owed it to them and to my daughter to make certain they received the proper information about sexual matters. There is a five- year age difference between Ali and the twins, they have different fathers, and though there was never any suggestion of inappropriate conduct on their part, I was paranoid about custody issues due to my previous experiences with child welfare folks.

For that reason, I sent the boys to a psychologist when they were about to enter their teens. The boys had received some instruction at school about reproduction, mostly a very clinical, very scientific parts- and- process inventory that had little to do with their real world concerns. I wanted them to go to someone who could speak with them on their level about all kinds of matters that I would have never been able to bring up: nocturnal emissions, masturbation, intercourse, spontaneous erections, and all the other things that had a blush factor of 10 or more.

Along with a discussion about those issues, I wanted the therapist to help me instruct the boys on what was appropriate behavior— not simply sexually but socially— with members of the opposite sex. I knew that the boys had developed an interest in girls and women. I used to bring home outdated magazines from the off ice— People and Cosmopolitan, mostly— and Stephen and Phillip would read them. They both seemed to be drawn to the ones with the photos of female celebrities on the cover. That was fine and normal, but I also wanted them to learn that what they saw on the covers of the magazines and what was in store for them in reality were two different things.

Because of patient- client confidentiality issues— and even If there weren’t those constraints placed on a therapist, I wouldn’t have asked anyway— I don’t know and can’t tell you the details of the discussions the boys had with him. I respected their privacy enough and trusted in the therapist enough to simply take them to the appointments, sit patiently in the waiting room for the hour to lapse, and then drive the boys home. Later, when Doug learned that the boys had received some additional sex education through the therapist, he referred to him as “Doctor Las Vegas— what they discuss in his off ice stays in his off ice.” And that’s exactly as I intended it.

I knew my limitations, and I didn’t want them to interfere with the twins getting the information they needed and deserved. I was willing to let go of my control over the situation and let someone with far more expertise than I possessed do the job for me.

Stephen and Phillip have both expressed a desire, as I’ve mentioned before, to date and to eventually marry. Stephen’s first foray into high school romance serves as an object lesson in the ways of the autistic heart.

Stephen’s self- confidence was boosted enormously by the press attention he was receiving. As one student told me when I went to pick the boys up from school— they were now considered BMOCs. I had no idea that kids in the nineties still used a phrase from my teenage years, an expression that even predates me, but if being a Big Man on Campus was what the twins were, then I was glad. I knew, of course, that this description was exaggerated. Agoura High was like most schools, where the football quarterback and the homecoming queen garnered the attention of the jocks and preps, were silently mocked by the skater dudes and the other social outcasts, and looked at with envious longing by the wannabes. There were other cliques, I’m sure, and Stephen’s running achievements meant he was no longer among the anonymous, faceless crowd who secretly hoped for attention but found comfort in blending in. Though the Supreme Court had outlawed one kind of segregation in the schools, another remained deeply entrenched— the cool kids and the not- cool kids could occupy the same physical space, but in a physics- defying fact of high school life, the cool kids could render the others invisible and mute.

One young woman who seemed to operate beyond all the laws of the social physics of high school was Laura Jakosky. She was the lead runner on the girls’ cross- country team, she excelled academically, she was a student leader, and she was one of the most popular and attractive girls at the school. A leggy blonde with long hair and eyes the color of the Pacific, she was a walking Beach Boys’ song. One day, she did the unexpected. She broke ranks and asked Stephen his name. Who could blame him for falling instantly in love?

Each spring, the school held a Vice- Versa dance, their variation on the Sadie Hawkins Day dance, when the girls were expected to ask the boys out. Stephen convinced himself that Laura liked him and was going to ask him, so he purchased tickets to the dance and waited expectantly for her to call. We learned much of this after the fact. We knew that Stephen liked Laura. Doug and I both tried to talk to him about what was appropriate behavior and how he could go about asking her out on a date If that was what he wanted to do. Doug tried to impress upon Stephen the importance of not just being a gentleman but being confident and specific. He said that he should have a plan in mind for what he wanted to do on the date. He showed Stephen the movie section in the newspaper and told him that instead of just lamely asking a girl if she wanted to go out, he should say that he wanted to take her to the movies and that X was playing at this time at this theater and would she like to go.

We made it clear, or so we hoped, that we weren’t talking about Laura specifically but with girls generally. We were trying to remain neutral on the Laura issue. We were in a tough spot. We knew Laura because of her association with the cross- country team, and we knew her by her very positive reputation. We knew that a girl like Laura could pick and choose from among the cream of the crop of young men at Agoura High School. How do you explain to your teenage son, one whose self- confidence was so newly formed as to be especially fragile, that he was aiming too high, that, as the expression goes, Laura was out of his league?

We could sense that Stephen was setting himself up for a painful fall, but who among us hasn’t been in the same position? Though the inevitable would likely hurt, we felt that if we really wanted Stephen to socialize and integrate himself fully into life, some painful lessons were going to come his way. As hard as it was for me to let go, I knew in this case that my interfering would really disrupt Stephen’s development. I had one ally in this regard.

Apparently, Stephen had made his feelings for Laura known. He didn’t verbalize them, but when he was at track practice, at every opportunity he would maneuver around so that he could stand next to her. He lacked the courage and skills to say hello and engage her in conversation, so he was essentially lurking around. Of course, Laura knew about Stephen’s condition and was patient with him, but she must have expressed her discomfort to her teammates. Word got back to Coach Duley, but he refused to intervene on their behalf. He later told me that no matter who was involved, unless something illegal or potentially threatening was going on (which there wasn’t), he would have expected the kids to sort things out themselves. He wasn’t the type to cross the line and get involved in their personal lives unless there was a clear need to do so. We didn’t know anything about this until after the fact.

Days before the dance, Stephen must have learned that Laura was not going with him but with someone else. He ran off instead of going to practice, a less- than- mature thing to do and a habit of his when he was disappointed. When I went to school to pick him up after practice, I immediately called the police when I learned he hadn’t shown up. He had already been missing for three hours. The Lost Hills Sheriffsent forty deputies and park officers; they were joined by what must have been a hundred volunteers from the community— athletes, parents, store owners, and even one elderly woman whose self- sacrifice and compassion had me in tears.

The search went on, and desperate for clues, one of the deputies asked Phillip if he had any idea where Stephen might have gone. Not one to willingly disappoint anyone, Phillip said, “Yes.” For two more hours a trio of deputies trailed after Phillip as he led them around and through the campus. He talked to them about his heroes, John Lennon and Eric Clapton. He asked the officers if they played a musical instrument. They tried to keep Phillip focused on finding Stephen, but Phillip had found three new friends. He would have kept them out there all night, but when the deputies worked their way back toward the front of the school, they spotted Stephen in a squad car. He was clutching a note in his hand. He’d written a love letter to Laura while hiding in the Andy Gump Porta- Potty less than a mile from the school.

I went to get him and did my best to find the words to console him, but he really didn’t want to hear anything from me. I felt so bad for him. Coach Duley was sympathetic and called Stephen the next day to give him the “other fish in the sea” speech. I knew it was too soon to talk to Stephen about making more appropriate choices in terms of how he expressed his disappointment. Running away wouldn’t solve anything, but I knew that he was angry, embarrassed, and possibly hoping that by running away he was showing Laura and everyone else the depths of his feelings for her. Though his choice didn’t demonstrate the greatest degree of emotional maturity, he was still just a kid, as much a victim of his hormones and lack of impulse control as any teen. He was confusing getting someone to feel sorry for him with really having a deep affection for him, a trap that quite a few adults I know sometimes fall into.

Laura’s family called us to explain her position. She wanted to be sure that Stephen understood, and that we understood, that she did like Stephen as a friend but that was all. I thanked them for phoning, wishing that Laura had made the call herself or, more especially, that she’d spoken to Stephen directly. We weren’t in any way blaming her, but we were still left with the difficult task of explaining some of the social complexities and nuances of the situation to our brokenhearted autistic son. Stephen tended to exist in a more black- and- white, on- or- off world of absolutes. I think that was why running appealed to him so much. You knew who the winners and losers were because of the absolute certainty of the stopwatch. There were few gray areas in athletic competition. If you did lose, you knew by exactly how much, and you could measure the amount you needed to improve to become a winner. Games of the heart, Stephen was coming to realize, were played by an entirely different set of rules.

While Stephen’s instincts and emotions led him to pursue Laura in the way he thought and felt was best, I was feeling my way along in the dark in dealing with the twins and their autistic adolescence. Letting go and learning to trust that my sons were resilient enough to deal with life’s bumps and bruises was by far, and remains, the most difficult thing I’ve ever had to do. Maybe this has been God’s way of testing me and making me a better person. I come from a long line of worriers, and maybe it was destiny to break that cycle somehow.

I know all parents worry about their kids. I know that my parents did and still do about me. I worry about all my kids equally. Ali is away at college, and I worry about her. She told me about an attempted rape in a campus parking garage, and I started to worry for her safety. Richard is in the Navy and away at sea on duty, and I worry about what might happen to his ship. I also worry about Doug. I worry about my dogs. I worry about my neighbors and the fires that swept through this part of Southern California. But with my autistic kids, the level or degree of worry I feel for and about them is somehow different from all the other worries I have and different from what I imagine other parents experience.

Maybe I’m wrong about that; maybe all this worrying and wondering and struggling to let go is normal. Maybe I’m no different and no more special than any other parent when it comes to the twin desires to hang on and to let go, to honor Phillip’s cry of “Freedom” and to protect them from the harm that independence might sometime bring.

Although I had mixed feelings about them falling in love, I firmly believed that Stephen and Phillip had the right to apply for and to try to get their driver’s licenses. If they passed the written and the driving tests, demonstrating the competency that any other citizen possessed, then why not?

On the other hand, I had some pretty good why- nots in mind. The anxiety level they both exhibited in new situations, especially when exposed to things like loud noises, would potentially make them a danger to themselves and to other drivers. All the medications that Phillip was on and the unpredictable interactions among those drugs didn’t make him a good candidate for driving. When I stacked those reasons up against their strong desire to drive, and what more potent symbol of a teen’s freedom and independence exists than driving, I was torn. I didn’t want to be the one to stand in the way of their dream being fulfilled. To give you a better idea of how much driving meant to him, Phillip had written a song aptly titled “The DMV Song.” I didn’t like to ever play favorites, but I could reasonably imagine Stephen being able to earn his license. With Phillip, I thought the odds were stacked against him.

On one occasion, I took them both to the DMV office. I turned them loose after telling them which line to stand in. I sat in a waiting area with my fingers crossed, hoping that they’d both fail the written test. I knew that would greatly disappoint them both, but failing on their own was better than me not allowing them to do something they wanted so badly to do. The first time Phillip took the written test, I could see that he was struggling. I don’t know if it was nerves or what, but I could read the panic in his eyes as he scanned the questions.

That surprised me since they had both studied very hard for the test. When Phillip completed his test and brought it to the clerk, he kind of shuffled up and looked as though he was about to collapse with in himself. It took a few moments for him to get his score, and when he was called back up, it was clear that he hadn’t passed. I breathed a deep sigh of relief. Stephen had already passed the written portion of the exam and was in line to take the vision test. I now only had one to worry about.

Then I noticed that the clerk had taken Phillip aside. I didn’t want to make a scene, so I stood up and inched my way closer to where the pair was standing. The clerk, obviously very sympathetic to Phillip’s plight, was asking him a series of really basic questions about driving. The next thing I knew, he was shaking Phillip’s hand and congratulating him for passing the written test. I couldn’t believe it. It was a nice gesture, but all I could think of was that he was hoping that Phillip wouldn’t make it past some of the other hurdles he had yet to face.

As it turned out, neither of the boys passed the driving portion of the exam. I was so relieved. They both vowed to work harder and to pass the next time. As bad as I felt rooting against my sons, I knew that in the end their not getting to drive was a good thing. I would hate for them to do harm to themselves and to another driver or pedestrian. Balancing what is right for them with the needs of the larger community is an ongoing task.

I believe that someday they will both be able to drive. Quite a few high- functioning autistics do, and I feel that once the twins mature a little more and learn to deal better with loud noises and such, they will be good drivers. One thing is for sure: they would never get lost. Stephen especially is like a human Global Positioning Satellite. I’m not fond of driving, and I frequently get lost, but if Stephen or Phillip is in the car with me, I never have to worry about finding my way. It is uncanny how we can be traveling in some unfamiliar place and they always manage to get me back on the road to home.

The twins still talk about getting their licenses, and I think that one day they will. They just have to be patient, a virtue whose importance we all became acutely aware of throughout the years.

As for that other major adolescent rite of passage— first love— I knew I wouldn’t be able to have the proverbial birds and the bees discussion with Stephen and Phillip. I knew that my nervousness and awkward attempts to communicate with them about reproduction and sexual intimacy would send the wrong signal to them. If I stuttered and stammered, hemmed and hawed, turned beet red and blanched at any of their questions I thought were too frank, all I would do was add to their confusion. I also knew that I owed it to them and to my daughter to make certain they received the proper information about sexual matters. There is a five- year age difference between Ali and the twins, they have different fathers, and though there was never any suggestion of inappropriate conduct on their part, I was paranoid about custody issues due to my previous experiences with child welfare folks.

For that reason, I sent the boys to a psychologist when they were about to enter their teens. The boys had received some instruction at school about reproduction, mostly a very clinical, very scientific parts- and- process inventory that had little to do with their real world concerns. I wanted them to go to someone who could speak with them on their level about all kinds of matters that I would have never been able to bring up: nocturnal emissions, masturbation, intercourse, spontaneous erections, and all the other things that had a blush factor of 10 or more.

Along with a discussion about those issues, I wanted the therapist to help me instruct the boys on what was appropriate behavior— not simply sexually but socially— with members of the opposite sex. I knew that the boys had developed an interest in girls and women. I used to bring home outdated magazines from the off ice— People and Cosmopolitan, mostly— and Stephen and Phillip would read them. They both seemed to be drawn to the ones with the photos of female celebrities on the cover. That was fine and normal, but I also wanted them to learn that what they saw on the covers of the magazines and what was in store for them in reality were two different things.

Because of patient- client confidentiality issues— and even If there weren’t those constraints placed on a therapist, I wouldn’t have asked anyway— I don’t know and can’t tell you the details of the discussions the boys had with him. I respected their privacy enough and trusted in the therapist enough to simply take them to the appointments, sit patiently in the waiting room for the hour to lapse, and then drive the boys home. Later, when Doug learned that the boys had received some additional sex education through the therapist, he referred to him as “Doctor Las Vegas— what they discuss in his off ice stays in his off ice.” And that’s exactly as I intended it.

I knew my limitations, and I didn’t want them to interfere with the twins getting the information they needed and deserved. I was willing to let go of my control over the situation and let someone with far more expertise than I possessed do the job for me.

Stephen and Phillip have both expressed a desire, as I’ve mentioned before, to date and to eventually marry. Stephen’s first foray into high school romance serves as an object lesson in the ways of the autistic heart.

Stephen’s self- confidence was boosted enormously by the press attention he was receiving. As one student told me when I went to pick the boys up from school— they were now considered BMOCs. I had no idea that kids in the nineties still used a phrase from my teenage years, an expression that even predates me, but if being a Big Man on Campus was what the twins were, then I was glad. I knew, of course, that this description was exaggerated. Agoura High was like most schools, where the football quarterback and the homecoming queen garnered the attention of the jocks and preps, were silently mocked by the skater dudes and the other social outcasts, and looked at with envious longing by the wannabes. There were other cliques, I’m sure, and Stephen’s running achievements meant he was no longer among the anonymous, faceless crowd who secretly hoped for attention but found comfort in blending in. Though the Supreme Court had outlawed one kind of segregation in the schools, another remained deeply entrenched— the cool kids and the not- cool kids could occupy the same physical space, but in a physics- defying fact of high school life, the cool kids could render the others invisible and mute.

One young woman who seemed to operate beyond all the laws of the social physics of high school was Laura Jakosky. She was the lead runner on the girls’ cross- country team, she excelled academically, she was a student leader, and she was one of the most popular and attractive girls at the school. A leggy blonde with long hair and eyes the color of the Pacific, she was a walking Beach Boys’ song. One day, she did the unexpected. She broke ranks and asked Stephen his name. Who could blame him for falling instantly in love?

Each spring, the school held a Vice- Versa dance, their variation on the Sadie Hawkins Day dance, when the girls were expected to ask the boys out. Stephen convinced himself that Laura liked him and was going to ask him, so he purchased tickets to the dance and waited expectantly for her to call. We learned much of this after the fact. We knew that Stephen liked Laura. Doug and I both tried to talk to him about what was appropriate behavior and how he could go about asking her out on a date If that was what he wanted to do. Doug tried to impress upon Stephen the importance of not just being a gentleman but being confident and specific. He said that he should have a plan in mind for what he wanted to do on the date. He showed Stephen the movie section in the newspaper and told him that instead of just lamely asking a girl if she wanted to go out, he should say that he wanted to take her to the movies and that X was playing at this time at this theater and would she like to go.

We made it clear, or so we hoped, that we weren’t talking about Laura specifically but with girls generally. We were trying to remain neutral on the Laura issue. We were in a tough spot. We knew Laura because of her association with the cross- country team, and we knew her by her very positive reputation. We knew that a girl like Laura could pick and choose from among the cream of the crop of young men at Agoura High School. How do you explain to your teenage son, one whose self- confidence was so newly formed as to be especially fragile, that he was aiming too high, that, as the expression goes, Laura was out of his league?

We could sense that Stephen was setting himself up for a painful fall, but who among us hasn’t been in the same position? Though the inevitable would likely hurt, we felt that if we really wanted Stephen to socialize and integrate himself fully into life, some painful lessons were going to come his way. As hard as it was for me to let go, I knew in this case that my interfering would really disrupt Stephen’s development. I had one ally in this regard.

Apparently, Stephen had made his feelings for Laura known. He didn’t verbalize them, but when he was at track practice, at every opportunity he would maneuver around so that he could stand next to her. He lacked the courage and skills to say hello and engage her in conversation, so he was essentially lurking around. Of course, Laura knew about Stephen’s condition and was patient with him, but she must have expressed her discomfort to her teammates. Word got back to Coach Duley, but he refused to intervene on their behalf. He later told me that no matter who was involved, unless something illegal or potentially threatening was going on (which there wasn’t), he would have expected the kids to sort things out themselves. He wasn’t the type to cross the line and get involved in their personal lives unless there was a clear need to do so. We didn’t know anything about this until after the fact.

Days before the dance, Stephen must have learned that Laura was not going with him but with someone else. He ran off instead of going to practice, a less- than- mature thing to do and a habit of his when he was disappointed. When I went to school to pick him up after practice, I immediately called the police when I learned he hadn’t shown up. He had already been missing for three hours. The Lost Hills Sheriffsent forty deputies and park officers; they were joined by what must have been a hundred volunteers from the community— athletes, parents, store owners, and even one elderly woman whose self- sacrifice and compassion had me in tears.

The search went on, and desperate for clues, one of the deputies asked Phillip if he had any idea where Stephen might have gone. Not one to willingly disappoint anyone, Phillip said, “Yes.” For two more hours a trio of deputies trailed after Phillip as he led them around and through the campus. He talked to them about his heroes, John Lennon and Eric Clapton. He asked the officers if they played a musical instrument. They tried to keep Phillip focused on finding Stephen, but Phillip had found three new friends. He would have kept them out there all night, but when the deputies worked their way back toward the front of the school, they spotted Stephen in a squad car. He was clutching a note in his hand. He’d written a love letter to Laura while hiding in the Andy Gump Porta- Potty less than a mile from the school.

I went to get him and did my best to find the words to console him, but he really didn’t want to hear anything from me. I felt so bad for him. Coach Duley was sympathetic and called Stephen the next day to give him the “other fish in the sea” speech. I knew it was too soon to talk to Stephen about making more appropriate choices in terms of how he expressed his disappointment. Running away wouldn’t solve anything, but I knew that he was angry, embarrassed, and possibly hoping that by running away he was showing Laura and everyone else the depths of his feelings for her. Though his choice didn’t demonstrate the greatest degree of emotional maturity, he was still just a kid, as much a victim of his hormones and lack of impulse control as any teen. He was confusing getting someone to feel sorry for him with really having a deep affection for him, a trap that quite a few adults I know sometimes fall into.

Laura’s family called us to explain her position. She wanted to be sure that Stephen understood, and that we understood, that she did like Stephen as a friend but that was all. I thanked them for phoning, wishing that Laura had made the call herself or, more especially, that she’d spoken to Stephen directly. We weren’t in any way blaming her, but we were still left with the difficult task of explaining some of the social complexities and nuances of the situation to our brokenhearted autistic son. Stephen tended to exist in a more black- and- white, on- or- off world of absolutes. I think that was why running appealed to him so much. You knew who the winners and losers were because of the absolute certainty of the stopwatch. There were few gray areas in athletic competition. If you did lose, you knew by exactly how much, and you could measure the amount you needed to improve to become a winner. Games of the heart, Stephen was coming to realize, were played by an entirely different set of rules.

While Stephen’s instincts and emotions led him to pursue Laura in the way he thought and felt was best, I was feeling my way along in the dark in dealing with the twins and their autistic adolescence. Letting go and learning to trust that my sons were resilient enough to deal with life’s bumps and bruises was by far, and remains, the most difficult thing I’ve ever had to do. Maybe this has been God’s way of testing me and making me a better person. I come from a long line of worriers, and maybe it was destiny to break that cycle somehow.

I know all parents worry about their kids. I know that my parents did and still do about me. I worry about all my kids equally. Ali is away at college, and I worry about her. She told me about an attempted rape in a campus parking garage, and I started to worry for her safety. Richard is in the Navy and away at sea on duty, and I worry about what might happen to his ship. I also worry about Doug. I worry about my dogs. I worry about my neighbors and the fires that swept through this part of Southern California. But with my autistic kids, the level or degree of worry I feel for and about them is somehow different from all the other worries I have and different from what I imagine other parents experience.

Maybe I’m wrong about that; maybe all this worrying and wondering and struggling to let go is normal. Maybe I’m no different and no more special than any other parent when it comes to the twin desires to hang on and to let go, to honor Phillip’s cry of “Freedom” and to protect them from the harm that independence might sometime bring.

Descriere

The inspiration for the Lifetime movie and a guide for parents confronting their autistic children's journeys to adulthood, this memoir recounts Morgan-Thomas' sons' determination to lead independent and happy adult lives.

Notă biografică

Corrine Morgan-Thomas