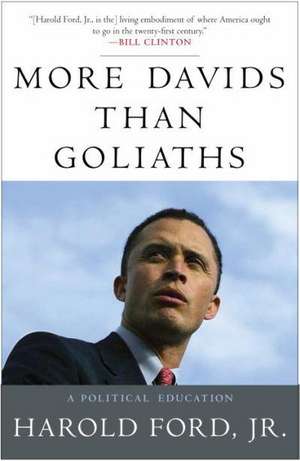

More Davids Than Goliaths: A Political Education

Autor Harold Ford, Jr.en Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 dec 2035

Reflecting on what he’s learned from his extended political family, the slings and arrows of the campaign trail, and those across our nation who inspire him, More Davids Than Goliaths explains Ford’s conviction, “At its best, leadership in government can solve, inspire, and heal.” Along the way, Ford reminds us that in America, there are more Davids than Goliaths, more solutions than problems, more that unites us than divides us.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 97.94 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 147

Preț estimativ în valută:

18.74€ • 19.64$ • 15.49£

18.74€ • 19.64$ • 15.49£

Carte nepublicată încă

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307408396

ISBN-10: 0307408396

Pagini: 256

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: Crown Publishing Group

Colecția Broadway

ISBN-10: 0307408396

Pagini: 256

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: Crown Publishing Group

Colecția Broadway

Notă biografică

Harold Ford, Jr., is an executive vice chairman at Bank of America in New York. In addition, he teaches public policy at New York University’s Wagner Graduate School of Public Service and chairs the Democratic Leadership Council. He and his wife, Emily, live in Manhattan.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

THE APPRENTICE

This is Harold Ford, Jr., and I’m campaigning for my daddy for Congress. If you want a better house to live in, better schools to go to, and lower cookie prices, vote for my daddy.” I made my first political ad when I was four years old. It was 1974, and my father was running for Congress. My mom propped me up on a brown folding table at the back of my dad’s campaign headquarters and I spoke into a microphone attached to a cassette recorder.

I did it in one take.

Politics was ingrained in me early. It was part of me in the best of ways. For my entire life, I’ve met and heard people, especially other politicians, talk about how they started early in politics by handing out leaflets, brochures, and so on. My start in politics was equally honest—a commercial for my dad on his first congressional campaign. In a lot of ways, politics was—and remains—a part of my genetic makeup, and, for that matter, so was my party identification. I learned to be a Democrat the old-fashioned way: I was told that I was going to be one by my father and mother.

The campaign headquarters was a comfortable setting for me. I was there almost every day. My folks would pick me up at preschool and take me to the headquarters, where I delighted in the hustle and bustle and the steady inrush and outrush of staff and volunteers. For as long as I can remember, I’ve loved being around people.

As a kid, I always felt comfortable around adults. I didn’t necessarily prefer adults over my peers, but sitting with, listening to, and talking in front of adults never really bothered me or made me nervous. I wasn’t overconfident or anything like that. But I wasn’t lacking confidence—I get that from both my mom and my dad. Nor was I different from other kids my age in that I enjoyed and played sports. It was more that I wanted to be a part of the conversation—I wanted to help in any way I could. I felt a particular but unarticulated closeness to the politics surrounding me—perhaps because it was my family involved and my dad’s name on the ballot.

A few days after I made the ad, I heard it on the radio. I was sitting between my parents in the car. My mother smiled. My father grinned. I remember, at a precocious moment, thinking at the time, “I enjoy talking, and I really enjoy talking about campaigning.” Although I didn’t appreciate what exactly my dad was going to do to get people better homes and kids better schools, I knew he was going to try.

After the ad, I started going to more and more campaign events with my parents. It isn’t uncommon for politicians to introduce their families or even to ask their families to join them onstage while they are speaking. And my dad would often do that. He would sometimes allow me to introduce him, and I often repeated my line from the radio ad. The cookie line was my favorite line in the introduction—my mother drafted that line. When introducing my dad, I always committed the additional lines to memory. I never used notes or read from a prepared text—even to this day, I don’t use prepared remarks. I will sometimes refer to notes, but never a written speech. I don’t use prepared remarks primarily because I find them hard to read with passion, sincerity, and force.

I remember speaking at one of my father’s congressional prayer breakfasts in Memphis when I was seven. My dad’s speaker that year was his congressional colleague and my parents’ longtime friend Andrew Young. I helped introduce Congressman Young. I reminded the audience how much a role model Congressman Young was to people of all ages, especially for aspiring politicians like me. Prior to the speech, I remember going with my dad and some other politicians to meet with Congressman Young in his hotel in downtown Memphis. I sat at the dining room table in the hotel with Congressman Young and my dad as they discussed politics. I was just absorbing. My dad’s focus was always people, especially hardworking poor people. My dad was listening closely to Congressman Young talk about how he and Maynard Jackson had built a black-white coalition in Atlanta premised on propelling black elected officials into high political offices and growing business opportunities for the entire Atlanta business community, including minority businesses. Memphis’s persistent and pernicious occupation with race had prevented us from electing an African American mayor and widening sustainable business opportunities and growth to black businesses in the city. My dad’s belief was that a racially diverse and successful Memphis business community was essential to better political and social cohesion in Memphis. One of the keys to realizing that dream was for the Memphis political landscape to become more racially and politically diverse first. Atlanta was a model for Memphis.

One of the things I learned from my dad at an early age about politics was never to allow jealousy, envy, or pettiness to get in the way of learning from a political peer. My dad inspired and taught a lot of politicians, younger and older, but he never shied away from learning himself. Andrew Young and Maynard Jackson are two southern politicians whom my dad respected and learned from.

Growing up in a political household seemed normal because it’s all I knew. There were three basic givens in the house for Jake, Isaac, and me. We had to do our homework every night, we had to go to church every Sunday (and oftentimes Sunday school), and we worked on political campaigns for my dad and my uncles.

There was only one of those I genuinely enjoyed and relished—campaigning. Don’t get me wrong, my parents didn’t force us to campaign, but it was expected. And my brothers loved it as well. But with all the expectations placed on us to campaign, there were not concurrent expectations for us to enter politics. My parents would have been as pleased or satisfied if any of us had elected to become a doctor, a teacher, a journalist, a scientist, a cop, or a lawyer—wherever our desires and abilities led us, they would have been fine with. Having said that, I don’t remember a time when politics, public service, and campaigns didn’t excite and drive me. Even after my parents moved us to Washington in 1979 during my dad’s third term in Congress, I very much looked forward to returning to Memphis in the summers, especially election summers, to join the campaign. The work for me was primarily grassroots—bumper stickering cars at shopping centers, putting up yard signs, and handing out campaign literature. The older I got, the more responsibility I was given. Eventually, I managed my dad’s campaigns and was responsible for more of the organizational aspects of the campaigns. I wrote the text of the literature, spoke on my dad’s behalf, organized fund-raising, and planned big events. But the grassroots work for me never stopped—even after he’d served ten terms in the Congress, my dad’s commitment to grass-roots campaigning never waned. We would always start and finish the day shaking hands, slapping on bumper stickers, and taking pictures with constituents at shopping centers, grocery stores, malls, and busy intersections. My passion for and comfort with retail politics developed honestly. It might even be genetic.

Every Sunday morning we had a ritual in the house. The arrangement was very straightforward—if you ate breakfast, you went to church. I ate every Sunday morning. My mother would fry chicken, boil rice, and bake biscuits almost every Sunday. Even my Jewish friends who would sleep over would be required to go to church with us in Washington if they had breakfast. Although my family never disavowed our membership at our home church in Memphis (Mt. Moriah-East Baptist Church, which is where my brothers and I were baptized by Reverend Melvin Charles Smith), we were visiting members at two churches in Washington: New Bethel Baptist, pastured by Reverend Walter Fauntroy, who was also Washington, D.C.’s delegate to Congress, and Metropolitan Baptist, pastured by Reverend H. Beecher Hicks. Initially, I was more comfortable in church in Memphis, but as we attended more and more services in D.C., I grew to love New Bethel and Metropolitan. Reverend Fauntroy was as good a gospel singer in the pulpit as he was a pastor.

On the campaign trail in 1996 during my first run for Congress, I’d often ask young parents where they attended church. I was often surprised by their answers, which can be best paraphrased as “I go to New Salem, but I can’t get my kids to go.” Or, “I attend Olive Grove Baptist, but I can’t get my kids to go.” I was surprised, if not shocked, to hear this because when I was growing up, kids didn’t have decision-making authority like that in any home that I knew of. Although eating breakfast was what triggered the requirement to go to church in my house, I always knew that even if I didn’t eat breakfast, I was still going to church. In short, there was no opt-out provision in the Ford household.

Sometimes we even had to go to church during the week.

When my parents were attending political and social events in the evenings, they would leave my brothers and me with one of the most wonderful families I’ve ever known, the Ingrams. The Ingram girls, Lori and Debra, were our primary babysitters. Their mother, Mrs. Ingram, was the moral pillar of the household, and she insisted that everyone accompany her to Lambert Church of God in Christ on Wednesday nights. We knew that if we went to the Ingrams’ on a Wednesday night, we would be going to church. It didn’t occur to us to argue. Wednesday night church wasn’t ideal, since we had just gone to church three days earlier and were due again in church four days later. However, Wednesday night church was bearable because the choir sang well at Lambert, and the pastor’s sermon was not as long on Wednesday as it was on Sunday. Although, Church of God in Christ sermons were always longer.

On Sunday, the thought of after-church dinner eased some of the pain of sitting through services.

From the Hardcover edition.

This is Harold Ford, Jr., and I’m campaigning for my daddy for Congress. If you want a better house to live in, better schools to go to, and lower cookie prices, vote for my daddy.” I made my first political ad when I was four years old. It was 1974, and my father was running for Congress. My mom propped me up on a brown folding table at the back of my dad’s campaign headquarters and I spoke into a microphone attached to a cassette recorder.

I did it in one take.

Politics was ingrained in me early. It was part of me in the best of ways. For my entire life, I’ve met and heard people, especially other politicians, talk about how they started early in politics by handing out leaflets, brochures, and so on. My start in politics was equally honest—a commercial for my dad on his first congressional campaign. In a lot of ways, politics was—and remains—a part of my genetic makeup, and, for that matter, so was my party identification. I learned to be a Democrat the old-fashioned way: I was told that I was going to be one by my father and mother.

The campaign headquarters was a comfortable setting for me. I was there almost every day. My folks would pick me up at preschool and take me to the headquarters, where I delighted in the hustle and bustle and the steady inrush and outrush of staff and volunteers. For as long as I can remember, I’ve loved being around people.

As a kid, I always felt comfortable around adults. I didn’t necessarily prefer adults over my peers, but sitting with, listening to, and talking in front of adults never really bothered me or made me nervous. I wasn’t overconfident or anything like that. But I wasn’t lacking confidence—I get that from both my mom and my dad. Nor was I different from other kids my age in that I enjoyed and played sports. It was more that I wanted to be a part of the conversation—I wanted to help in any way I could. I felt a particular but unarticulated closeness to the politics surrounding me—perhaps because it was my family involved and my dad’s name on the ballot.

A few days after I made the ad, I heard it on the radio. I was sitting between my parents in the car. My mother smiled. My father grinned. I remember, at a precocious moment, thinking at the time, “I enjoy talking, and I really enjoy talking about campaigning.” Although I didn’t appreciate what exactly my dad was going to do to get people better homes and kids better schools, I knew he was going to try.

After the ad, I started going to more and more campaign events with my parents. It isn’t uncommon for politicians to introduce their families or even to ask their families to join them onstage while they are speaking. And my dad would often do that. He would sometimes allow me to introduce him, and I often repeated my line from the radio ad. The cookie line was my favorite line in the introduction—my mother drafted that line. When introducing my dad, I always committed the additional lines to memory. I never used notes or read from a prepared text—even to this day, I don’t use prepared remarks. I will sometimes refer to notes, but never a written speech. I don’t use prepared remarks primarily because I find them hard to read with passion, sincerity, and force.

I remember speaking at one of my father’s congressional prayer breakfasts in Memphis when I was seven. My dad’s speaker that year was his congressional colleague and my parents’ longtime friend Andrew Young. I helped introduce Congressman Young. I reminded the audience how much a role model Congressman Young was to people of all ages, especially for aspiring politicians like me. Prior to the speech, I remember going with my dad and some other politicians to meet with Congressman Young in his hotel in downtown Memphis. I sat at the dining room table in the hotel with Congressman Young and my dad as they discussed politics. I was just absorbing. My dad’s focus was always people, especially hardworking poor people. My dad was listening closely to Congressman Young talk about how he and Maynard Jackson had built a black-white coalition in Atlanta premised on propelling black elected officials into high political offices and growing business opportunities for the entire Atlanta business community, including minority businesses. Memphis’s persistent and pernicious occupation with race had prevented us from electing an African American mayor and widening sustainable business opportunities and growth to black businesses in the city. My dad’s belief was that a racially diverse and successful Memphis business community was essential to better political and social cohesion in Memphis. One of the keys to realizing that dream was for the Memphis political landscape to become more racially and politically diverse first. Atlanta was a model for Memphis.

One of the things I learned from my dad at an early age about politics was never to allow jealousy, envy, or pettiness to get in the way of learning from a political peer. My dad inspired and taught a lot of politicians, younger and older, but he never shied away from learning himself. Andrew Young and Maynard Jackson are two southern politicians whom my dad respected and learned from.

Growing up in a political household seemed normal because it’s all I knew. There were three basic givens in the house for Jake, Isaac, and me. We had to do our homework every night, we had to go to church every Sunday (and oftentimes Sunday school), and we worked on political campaigns for my dad and my uncles.

There was only one of those I genuinely enjoyed and relished—campaigning. Don’t get me wrong, my parents didn’t force us to campaign, but it was expected. And my brothers loved it as well. But with all the expectations placed on us to campaign, there were not concurrent expectations for us to enter politics. My parents would have been as pleased or satisfied if any of us had elected to become a doctor, a teacher, a journalist, a scientist, a cop, or a lawyer—wherever our desires and abilities led us, they would have been fine with. Having said that, I don’t remember a time when politics, public service, and campaigns didn’t excite and drive me. Even after my parents moved us to Washington in 1979 during my dad’s third term in Congress, I very much looked forward to returning to Memphis in the summers, especially election summers, to join the campaign. The work for me was primarily grassroots—bumper stickering cars at shopping centers, putting up yard signs, and handing out campaign literature. The older I got, the more responsibility I was given. Eventually, I managed my dad’s campaigns and was responsible for more of the organizational aspects of the campaigns. I wrote the text of the literature, spoke on my dad’s behalf, organized fund-raising, and planned big events. But the grassroots work for me never stopped—even after he’d served ten terms in the Congress, my dad’s commitment to grass-roots campaigning never waned. We would always start and finish the day shaking hands, slapping on bumper stickers, and taking pictures with constituents at shopping centers, grocery stores, malls, and busy intersections. My passion for and comfort with retail politics developed honestly. It might even be genetic.

Every Sunday morning we had a ritual in the house. The arrangement was very straightforward—if you ate breakfast, you went to church. I ate every Sunday morning. My mother would fry chicken, boil rice, and bake biscuits almost every Sunday. Even my Jewish friends who would sleep over would be required to go to church with us in Washington if they had breakfast. Although my family never disavowed our membership at our home church in Memphis (Mt. Moriah-East Baptist Church, which is where my brothers and I were baptized by Reverend Melvin Charles Smith), we were visiting members at two churches in Washington: New Bethel Baptist, pastured by Reverend Walter Fauntroy, who was also Washington, D.C.’s delegate to Congress, and Metropolitan Baptist, pastured by Reverend H. Beecher Hicks. Initially, I was more comfortable in church in Memphis, but as we attended more and more services in D.C., I grew to love New Bethel and Metropolitan. Reverend Fauntroy was as good a gospel singer in the pulpit as he was a pastor.

On the campaign trail in 1996 during my first run for Congress, I’d often ask young parents where they attended church. I was often surprised by their answers, which can be best paraphrased as “I go to New Salem, but I can’t get my kids to go.” Or, “I attend Olive Grove Baptist, but I can’t get my kids to go.” I was surprised, if not shocked, to hear this because when I was growing up, kids didn’t have decision-making authority like that in any home that I knew of. Although eating breakfast was what triggered the requirement to go to church in my house, I always knew that even if I didn’t eat breakfast, I was still going to church. In short, there was no opt-out provision in the Ford household.

Sometimes we even had to go to church during the week.

When my parents were attending political and social events in the evenings, they would leave my brothers and me with one of the most wonderful families I’ve ever known, the Ingrams. The Ingram girls, Lori and Debra, were our primary babysitters. Their mother, Mrs. Ingram, was the moral pillar of the household, and she insisted that everyone accompany her to Lambert Church of God in Christ on Wednesday nights. We knew that if we went to the Ingrams’ on a Wednesday night, we would be going to church. It didn’t occur to us to argue. Wednesday night church wasn’t ideal, since we had just gone to church three days earlier and were due again in church four days later. However, Wednesday night church was bearable because the choir sang well at Lambert, and the pastor’s sermon was not as long on Wednesday as it was on Sunday. Although, Church of God in Christ sermons were always longer.

On Sunday, the thought of after-church dinner eased some of the pain of sitting through services.

From the Hardcover edition.