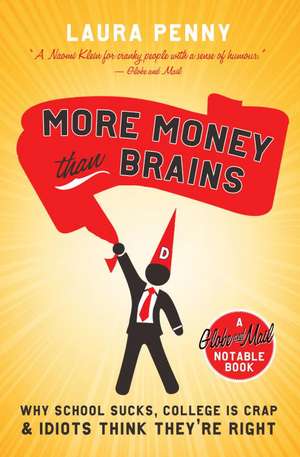

More Money Than Brains: Why School Sucks, College Is Crap, & Idiots Think They're Right: Globe and Mail Notable Books

Autor Laura Pennyen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mar 2011

Public education in the United States is in such pitiful shape, the president wants to replace it. Test results from Canadian public schools indicate that Canadian students are at least better at taking tests than their American cousins. On both sides of the border, education is rapidly giving way to job training, and learning how to think for yourself and for the sake of dipping into the vast ocean of human knowledge is going distinctly out of fashion.

It gets worse, says Laura Penny, university lecturer and scathingly funny writer. Paradoxically, in the two nations that have among the best universities, libraries, and research institutions in the world, intellectuals are largely distrusted and yelping ignoramuses now clog the arenas of public discourse.

A brilliant defence of the humanities and social sciences, More Money Than Brains takes a deadly and extremely funny aim at those who would dumb us down.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 102.70 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 154

Preț estimativ în valută:

19.66€ • 20.47$ • 16.61£

19.66€ • 20.47$ • 16.61£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780771070495

ISBN-10: 0771070497

Pagini: 250

Dimensiuni: 132 x 201 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: McClelland & Stewart

Seria Globe and Mail Notable Books

ISBN-10: 0771070497

Pagini: 250

Dimensiuni: 132 x 201 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: McClelland & Stewart

Seria Globe and Mail Notable Books

Recenzii

"More Money Than Brains is a ferocious defence of the arts and humanities against the philistine influence of Homo economicus (subspecies Goldman Sachsus). . . [Penny's] unflinching willingness to entertain puts her light years ahead of her Canadian competitors."

— Globe and Mail

"An unflinching indictment of North American education, politics and media."

— Toronto Star

From the Hardcover edition.

— Globe and Mail

"An unflinching indictment of North American education, politics and media."

— Toronto Star

From the Hardcover edition.

Cuprins

One Don’t Need No Edjumacation

Two At the Arse End of the Late, Great Enlightenment

Three Is Our Schools Sucking?

Four Screw U or Hate My Professors

Five Bully vs. Nerd: On the Persistence of Freedumb in Political Life

Six More Is Less: The Media-Entertainment Perplex

Seven If You’re So Smart, Why Ain’t You Rich?

Notes

From the Hardcover edition.

Two At the Arse End of the Late, Great Enlightenment

Three Is Our Schools Sucking?

Four Screw U or Hate My Professors

Five Bully vs. Nerd: On the Persistence of Freedumb in Political Life

Six More Is Less: The Media-Entertainment Perplex

Seven If You’re So Smart, Why Ain’t You Rich?

Notes

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Chapter One

DON’T NEED NO EDJUMACATION

When I was a bespectacled baby nerd, pudgy, precocious prey for bullies, my parents consoled me with a beautiful lie. Someday, in magical places called college and work, being smart would be cool. I’d have the last laugh while the bullies were slaving away at crummy jobs. My mom and dad said youth was their time to shine, the high point for the popular, truculent lunkheads who mocked spelling bees and science fairs. Their lives would be all downhill after grade 12. Then nerds like me would become doctors and lawyers and maybe even prime minister, and profit from the dimwittedness of our former tormentors. Let ’em have their stupid dances and hockey games, they said. The future belonged to the weird kids who dug microscopes and dictionaries.

This, like many of my parents’ reassuring fibs, was partly true. There was no Santa, but there were plenty of Santas in the malls every December. The power of nerdiness did indeed propel many of my fellow Poindexters into respectable professions. The Poindexters ߝ the pallid, indoorsy, owlish sorts who always got picked last for teams ߝ have become coders and chemists and brokers and communications experts. But the struggle between bullies and nerds certainly did not end, as promised, when we graduated. Nor do nerds always emerge victorious in the contests of adult life. The bullies persevered and proliferated, went online and on TV and the radio, into politics and industry, and found new venues for numerous variations on a familiar theme: Fuck you, four-eyes.

I am not surprised that bullies continue to hate nerds, that the dudes who shove weedy science fair winners into lockers grow up to reject carbon taxes and vote for “strong” leaders. No, what shocks me is the number of self-hating nerds who are willing to pander to the bullies, the countless pundits and politicos who deploy their A-student skills in the service of anti-intellectualism.

This anti-intellectualism is at odds with all our talk about the importance of good schools. North Americans lavish a lot of rhetoric and resources on education. Politicians, pundits, business leaders, and concerned citizens natter on about the need to train workers to stay competitive in a global information economy, where knowledge is power. Post-secondary enrolment has reached record highs and private colleges of varying legitness have sprung up all over North America to cater to our seemingly insatiable hunger for classes. We also spend millions on books, toys, DVDs, video games, and supplements that claim to boost young ߝ or aging ߝ brains.

Never have so many been so schooled! But all this extra education has not turned the majority of North Americans into nerds, or nerdophiles. Our well-intentioned attempts to push and prod every semi-sentient kid through university seem to be backfiring. More people spending money and time on degrees has produced a surprising toxic side effect: more people who hate school ߝ and nerds.

The bachelor’s degree has become a costly high-school diploma, the new middle-class normal. Ergo, higher ed has been demoted to the level of a racket, a swindle, a series of pointless exertions one must complete to get the golden ticket to a good job. Listen to talk radio, watch Fox News, and you’ll learn that nerds are the real bullies. We dastardly bastards run the continent’s most widespread and shameless kid-snatching operation, spiriting people’s beloved offspring away for years so we can make them think (and drink) strange things for our own amusement and enrichment. The con has gone so well that we’ve started hustling suckers of all ages, luring hard-working adults and innocent seniors into our cunning scholastic traps. We extort money, effort, and time from taxpayers, students, and their families by threatening them with the dread spectre of unemployability. Then we teach material our students will never, ever use at work ߝ or anywhere else, for that matter. What do we know-it-alls know about work? It’s not like any of us has ever been there or done any.

Some of the people who spin this spiel are dropouts, such as Glenn Beck and Rush Limbaugh, who matriculated in morning-zoo shows and Top 40 Countdown radio. Beck and Limbaugh present their lack of academic credentials as proof of their moral and intellectual purity. At the same time, they ape the academics they claim to abhor: Limbaugh refers to himself as a professor from the Limbaugh Institute of Advanced Conservative Studies, and Beck scribbles Byzantine charts on a chalkboard as if he’s lecturing undergrads.

Then there are all their fellow-travellers, folks like Ann Coulter and Mark Levin, who have perfectly respectable degrees from elite schools ߝ the very academic institutions they incessantly deride. Politicians such as Dubya and Mitt Romney pull the same act. Pay no attention to my fancy degree or Harvard M.B.A. or the family fortunes that funded my first-class credentials. I’m a commonsensical commoner, a straighttalkin’ shitkicker just like you.

This exceedingly cynical summary of education ߝ that it is a swindle perpetrated by sophists ߝ is not that much of an exaggeration, alas. I’ve seen this view of education, phrased in much more vulgar terms, on many a message board. I’ve encountered more genteel versions of it in political speeches, editorials, and letters to the editor. This dismissive attitude is also evident in other popular phrases. Overeducated is now common parlance. Yet you never hear that someone is overrich or oversexy. Perpetual student is rarely a ringing endorsement of someone’s commitment to “lifelong learning,” to bum a bit of educratic euphemese. When we come across terms such as academic or theoretical in the media, they usually mean “irrelevant” or “imaginary,” mere mental exercises at a remove from the serious business of life. “You think you’re so smart” is never a compliment; the only thing worse than being smart is thinking that you are.

This attitude affects the way students approach university. Many want to get credentials that guarantee them super-awesome careers, but they don’t need no edjumacation. I’ve taught useless liberal-artsy subjects such as English and philosophy for a decade, and some of my students have been quite frank. No offence, Miss, but reading, thinking, and writing are wastes of time and boring as hell. They were never gonna use English . . . even though they had to do precisely that to bitch about its uselessness.

I love teaching, but there are days when I feel like a goddamn cartwright, like a practitioner and proponent of archaic and eccentric arts the kids will not need in the glorious analphabetic future. Sonnets, semicolons, and history might as well be alchemy or phrenology. As long as, like, people can, like, understand you, like, what’s the diff, y’know? Nobody cares about that old stuff. Nobody understands those long words. Nobody ever got hired because they could parse rhyme schemes or pick an argument apart or write a sentence, except for nerds like me, who squander our lives totally overanalyzing every little thing.

It would be a gross generalization to simply say that North Americans are ignorant and anti-intellectual. That would also make a really short book; I could print it in a hundred-point font, illustrate it with pictures of boobs and monster trucks, and then wait to see if it proved itself with boffo sales. It is more accurate to say that North Americans have a love-hate relationship with knowledge. We overestimate the value and reliability of certain uses of intelligence and can be quite disdainful towards mental pursuits that do not result in new stocks, synthetic foodstuffs, pills, or modes of conveyance. If we’re going to endure the insufferable tedium of learning, we do so for one reason: to make the big bucks.

We have, for the past few decades, steadily favoured money over brains. This is not to say that the moneyed are stupid. No, sir! The money-minded would not be so very moneyed if they were not armed with intellect, if they had not invested gross-buckets in their own stable of brains. It takes a surfeit of intellect to create complex financial instruments such as derivatives or to convince people that they need to deodorize, adorn, or alter yet another part of their body. The difference between money and brains is not a matter of how much either side of this divide knows. No, the big difference is the way they see knowledge and why they think intelligence is good. When I say “money,” I mean those who think you learn to earn, that our relation to knowledge is instrumental. When I say “brains,” I mean those who want to learn, who see knowing as an end in itself rather than the means to an end.

The mental work we have been exhorted to pursue is valuable because it is lucrative, not because it is smart. The kinds of thinking we have praised and celebrated, like the innovations of the Internet geek and the heroic entrepreneur or the efficiency of the ruthless CEO, are shrewd, technical ways of assessing the world, interpretations that turn complex states of affairs into calculable measures such as commodity prices and page clicks.

The irony is that our overwhelming emphasis on money, our conviction that markets are the smartest systems of all, has resulted in three recessions and one global market meltdown in the past thirty years. The more-money-than-brains mindset has obvious disadvantages for brains, and the 2008 fiscal collapse suggests that it is not so great for money either. But this crash also gives North Americans a chance to reassess our values and reconsider what we want from our political institutions, education systems, and markets. It is an opportune moment to think about we think about thinking, to examine our domestic intelligence failures and recalibrate the relation between money and brains.

The most obvious example of this shift is Barack Obama’s victory in the 2008 U.S. election, which pundits described as a victory for brains, a Revenge of the Nerds moment after the long, idiotic Bush nightmare. Carlin Romano, a professor and critic, wrote an article for the Chronicle of Higher Education in 2009 that sums up this sentiment nicely: “Philosopher-prez in chief and cosmopolitan in chief. After all this time, you figure, we were entitled to one. It looks as if we’ve got him.”

Obama has made admirable statements about education and his own good old-fashioned liberal arts degree. This is, admittedly, pretty sweet after nearly a decade of presidential pissing in the general direction of fancy book-learnin’. But I think it is way too hasty and optimistic to assume that Obama’s election means smarts are cool again, and that America resolves henceforth to be kinder and gentler to its oft-mocked eggheads.

Saying that Obama’s win marks the end of anti-intellectualism is a lot like saying it means the end of racism. Sure, it’s a good sign, but it’s not like the guy is six feet of antidote. Moreover, Obama’s presidency has inspired a seething right-wing backlash and stupefying coverage of his every snooty foible and flash of hauteur. Jeez, President College can’t even eat right like regular people! When he visited a greasy burger joint for the express purpose of supping with slovenly commoners, he had the audacity to request Dijon, a notoriously French mustard. A sign of Eurosocialist allegiances? Bien sûr.

The post-electoral Republican leadership vacuum was promptly filled by some of the right’s most gleefully proficient nerd-bashers, figures such as Sarah Palin, Glenn Beck, and Rush Limbaugh. All present themselves as mavericks, the only ones brave enough to speak emotive truth to factual power, outsiders marginalized by the uppity chattering classes in Hollywood, New York, and Washington.

These pseudo-populists insist that intellectuals are the real idiots. Ivy League city types think they are so smart, but that only goes to show how deluded and distant from common sense they are. As St. Ronald Reagan said in one of his most famous speeches ߝ 1964’s “A Time for Choosing” ߝ “it’s not that our liberal friends are ignorant. It’s just that they know so much that isn’t so.” The right-wing message is loud and clear: complex matters like climate change and foreign relations and the economy are complex because the elitists and the bureaucrats make them that way, to serve their own agendas and exclude just plain folks from the political process. Have any of these brainiacs ever done something really complicated, like run a Podunk town or make payroll? Didn’t think so!

The most rudimentary business skills or beavering one’s way to bosshood beat teaching or studying at some of the world’s finest universities. Once we’ve established that universities are a joke, a fiendishly elaborate scheme to overcharge people for beer, it is easy to discount any body of facts or ostensible expertise that emanates from them. If expertise in general is fake, a self-serving liberal chimera, then it stands to reason that experts are the biggest frauds of all: empty suits who have nothing to offer but words and dipsy-doodle ideas they expect working people to pay for. The people and the pols become fact-proof, and those who huck information at them align themselves with the patronizing pedants of Team Pantywaist.

This sort of anti-intellectualism is not new. It has been part of American political life ever since Andrew Jackson played the role of Old Hickory. Canadians like to fancy themselves above this sort of pseudo-populist politicking and think that it is the neighbours’ problem. But the Conservative Party’s campaigns against Liberal leaders Stéphane Dion and Michael Ignatieff were just as anti-intellectual, in their own stolid Canadian way, as the invective of the red-meat, redstate crowds at McCain-Palin rallies or anti-tax tea parties.

Professors like Romano, and the mainstream press, have covered Obama’s cosmopolitanism approvingly. They hope it will help ameliorate American relations with the rest of the world. Of course, this is also one of the things that drives Obama’s detractors wild. Drawing huge crowds in Europe, pronouncing Middle Eastern place names correctly, and nabbing a Nobel for nothing are all suspect. Being far’n-friendly is an un-American affectation.

Stephen Harper and company appealed to the Canadian version of this provincial small-mindedness when they ran negative ads that sneered at Ignatieff for describing himself as “horribly cosmopolitan.” His success in and familiarity with foreign lands was not an asset. No, instead he was cheating on Canada, whoring around with the likes of the BBC and Harvard.

I am not a fan of the man, but the Con campaign against him is so frigging brutal it makes me want to like Count Iggy. Consider this gem from their website, Ignatieff.me:

. . . Ignatieff has written next-to-nothing about

the economy ߝ the most pressing issue facing

Canada (and the world) ߝ today. Sure, he’ll talk

your ear off about abstract poetry, nationalism,

the importance of public intellectuals and the

British Royals. But when it comes to the practical

issues that affect real Canadian families ߝ especially

in a recession ߝ he’s invisible.

I love that they lead their shit list with abstract poetry, like Ignatieff is Björk or the ghost of Ezra Pound. The only thing worse than poetry? Abstract poetry, which exists solely to make students feel stupid and professors feel smug. Then there’s nationalism. Nope, can’t see how that relates to governing a nation. (Silly Libs, always thinking this is a country instead of an economy!) The gratuitous monarch-bashing is odd, given that HRH is still smiling gravely from our legal tender; perhaps a right-wing plan is in the works to replace her visage with the image of an oil derrick ߝ our one true queen and head of state.

The Cons and their ad hacks sloppily conflate two kinds of elitism. They mock Ignatieff for living in chi-chi digs in downtown Toronto instead of in the sticks or the burbs, the real Canada. He sips espresso and dips biscotti rather than sucking back double-doubles and Boston creams at the coffee dispensary of the people. Then they attack him for being a brain and a bore, for his sojourns in Yerp and at Harvard. To slam Ignatieff as “cosmopolitan” is typical right-wing nativism, divvying up the citizenry with criteria such as their proximity to livestock and dirt roads and their distance from gay bars and a decent latte. What is hilarious is seeing them mock Ignatieff ’s wealth and privilege. This from Conservatives? They love money, and the people who make lots of it.

Efforts to paint Ignatieff as a tourist, a mere visitor in his own land, play on the idea that intellectuals are always foreigners, outsiders from some theoretical fairyland. We see an even more extreme version of this notion in the Birther conspiracies that allege Obama was not born in America.

The small-town values message ߝ on both sides of the forty-ninth parallel ߝ is clear. Real patriots stay wherever Jesus and their mama’s cooter drop ’em.

This hostility to all things foreign or urban rides shotgun with anti-intellectualism; it’s all part of the same virulent reverse snobbery. Canadians and Americans express their reverse snobbery in slightly different ways, which I will return to later on when we look more closely at politics, in Chapter Five. I’ll also look at some of the differences between righty and lefty anti-intellectualism in that chapter. Republicans and the Alberta wing of Canadian politics have made exceptional contributions in the field of reverse snobbery, but they certainly do not have a monopoly on pseudo-populist poses and ideas. Democrats, Liberals, and the NDP also drop their G’s, chug brewskis, and sing the praises of Joe Six-Pack. They can’t attain high office without pandering to the lowest common denominator, especially when their opponents are spending so much money trying to convince the public that educated candidates are supercilious snobs.

Before we get into different flavours of anti-intellectual invective, let us look at some of the assumptions that disparate nerd-bashers share. Here is a short list of some of the most frequent allegations against the brainy.

1. Nerds are arrogant and think they are better than you.

Nerds do not think they are better than you. Nerds are better than you, in their particular fields, unless you happen to be an even more devoted nerd. This is a fact. However, I must admit, as a good Canadian, that I felt quite dickish typing the phrase “better than you.” North America’s shared egalitarian ideals are admirable, but pseudo-populism exploits those noble notions to level the culture, to raze evidence and argument, to belittle learning so that legitimate scientific research and the myths of creationists represent “both sides of the story.” A pediatrician and Playboy pin-up Jenny McCarthy are equally entitled to pontificate about the potential risks of vaccines. Any chump can go online and tell the world that Shakespeare blows and those dopey books about the sparkly vampire who won’t put out are the BEST EVAR!!1!!.

We have really put the duh in democracy, creating a perverse equality that entitles everyone to speak to every issue, regardless of how much they know about it. We see this on the news all the time. Ask celebrities about foreign policy, quiz the man on the street about the recession, read tweets and emails from the viewers. When a news show does invite experts to speak, producers make sure to get a batch representing “both sides” of the issue and have them squawk over each other for five barely intelligible minutes.

At the same time as the masses were being endowed with the inalienable right to rate everything on the Web or have their 140-character pensées voiced by CNN’s Rick Sanchez, economic inequality increased and social mobility declined. The moneyed elite became more so and the cultural elite became increasingly obsolete, drowned out and washed away by a tsunami of tweets.

Becoming a nerd is hardly a viable route to the top of the social food chain when nerds are the butt of jokes, the official spokespeople for imaginary things and superannuated crud. Anyone taking classics or history for the prestige is either at Oxford or stuck in 1909. The idea that someone would get a liberal arts education to secure a perch above the lowly hordes is a misreading of current cultural conditions, given the well-worn “D’ya want fries with that?” jokes that are your reward for completing a B.A.

Conversely, people constantly use money as a form of social display. Obese SUVs, blinged-out watches, brand-name clothing, and monster homes are more flagrant and effective signifiers of one’s worldly success and status than a head full of Hume or haikus. Several fields of human endeavour do a much better job of cultivating our feelings of better-than-you-ness than the long, humbling slog of study ߝ marketing, advertising, cosmetic dentistry, and a goodly chunk of the rap industry, to name but a few.

2. Nerds are lazy losers who expect money for nothing.

Are there lazy professors? Of course. Every occupation has its drag-ass dregs. What I take issue with is the caricature of professors as a slack species, a class of sluggards who teach a few hours a week and then get the whole summer off. Schoolteachers suffer from the same summers-off PR problem.

Education frequently bears the brunt of anti-public-sector sentiment. Those in the learning professions are painted as the most feckless wing of the ever-expanding civil service. This is one of the reasons why, in debates about public education, charter schools are now touted as the solution. We’ll talk about them in Chapter Three, “Is Our Schools Sucking?” For the time being, suffice it to say that the appeal of charter schools is their claim to cut three things that the more-money-than-brains mindset cannot abide: government, unions, and bureaucracy.

At least schoolteachers get some sympathy for coping with your junior snot-noses and teenage hoodlums. Profs don’t even get points for being glorified babysitters. And the hours we spend doing the rest of the gig ߝ committee meetings, research, presenting conference papers, and attending university schmoozefests ߝ are not always visible or legible to the general public, so they do not quite count as work either.

The idea that mental work is not really work is a hangover from old economies, from our days of hewing wood, drawing water, and making cars. But North America’s economies are increasingly dependent on service work and office work, on the kind of labour that makes more memos, meetings, and minutes than old-fangled objects. The dematerialization of labour and the deindustrializing of the North American economy are anxiety-making social changes that have cast many workers to the winds. It’s little wonder that many cling to mythic mid-twentieth-century notions about who really works for a living.

For example, shortly after Dubya began bailing out big banks and businesses, sales of Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged surged. The right-wing press read this as a sign of the Silent Majority’s resistance to creeping socialism. Government growth was going to make productive people go Galt! But all of Rand’s heroic capitalists triumph in industries that are now dead or bleeding. It’s easy to write potboilers that posit sharp moral distinctions between the makers and the takers when you live in a big-shouldered factory world where people still make things.

The collapse of the old manufacturing economy and the growth of the new service and financial economy make Rand’s ideology not just simplistic but downright nostalgic, a fantasia of a capitalism that never really was, and one that is highly unlikely to “return” soon. The producer/consumer distinction that drives her work is tough to sustain when our biggest product is consumption. It’s hard to guess what that shameless elitist Howard Roark would hate more: the socialist bank bailout, the skeevy second-handing mortgage peddlers, or the miles and miles of tacky abandoned McMansions.

The Rand revival is also weird considering what happened to the world’s most prominent Randian, Alan Greenspan. After years of being hailed as a guru for his outstanding achievements in the field of low, low interest rates as chairman of the Federal Reserve Board, Greenspan was hauled before Congress to explain why the markets had gone sour. He seemed unpleasantly surprised that the banking system could not rely on the virtue of selfishness as a regulatory restraint. When he was asked if his “ideology” had influenced his decisions, he admitted, “Yes, I’ve found a flaw. I don’t know how significant or permanent it is. But I’ve been very distressed by that fact.”

I can just picture Rand somewhere in Hell watching his testimony, eating Yankee dollars to calm her nerves as her acolyte apologized to the ultimate second-handers, those bureaucratic leeches and appropriators. (Ayn is doubly horrified when she realizes she is eating ߝ aaargh ߝ rubles. This is Hell!)

I digress. The main point is that academia is not the leisurely ivied stroll it is rumoured to be. If anything, a weak academic job market has made everyone but the exceptionally fortunate work much harder and has engendered the kind of competition, red in tooth and claw, that free marketeers always praise. Money for nothing is a much more accurate description of cashing in on swelling Internet stocks or soaring house prices. People love money for nothing! That’s why the lotto is so successful. That’s why Greenspan was hailed as a genius for making money as cheap as borscht. It’s money for thinking ߝ which looks suspiciously like nothing ߝ that the public seems to object to.

3. Nerds are social engineers who want to tell everyone what to do.

The only thing worse than a slothful prof is a bossy one. Intellectuals are always itching to advise, to embroil the public in diabolical social experiments. Daycare, gay rights, multiculturalism, and women working are good examples of the sort of social change the right thinks that nerds have engineered. Lefty allegations of evil egghead meddling point to things like cubic or part-fish tomatoes, weapons manufacturing, Big Pharma, and global trade agreements.

Different political groups, on the right and the left, often share a key presupposition: experts want to control you, thus expertise itself is a sinister force. Moreover, both agree that so-called experts only mess up the natural order of things. For example, conservatives contend that activist judges ruined heterosexual marriage with 2.3 kids, while lefties argue that Monsanto’s chemists wrecked gnarly local veggies grown in genuine organic manure.

In Anti-intellectualism in American Life, Richard Hofstader argues that the public increasingly distrust expertise precisely because they have become so dependent on it. As American society became more complex and highly organized after the world wars, the power of the experts grew, and people became increasingly nervous about their activities and proclivities, their sway over society. Complexity, Hofstader says, has “steadily whittled away the functions the ordinary citizen can intelligently and comprehendingly perform for himself.”

North American society has continued to become more complex, more technologically sophisticated, since Hofstader wrote these words nearly fifty years ago, in the early days of the TV age. We now rely on new experts, such as the programmers who keep our online banking sites up and running. Technology may make us feel like we are performing more functions for ourselves ߝ pay bills in your jammies with the click of a mouse! ߝ but comprehension fails many of us when the site or modem crashes. All those easy-to-navigate web pages are floating on an unseen sea of technical expertise.

Lack of computer savvy is just the tip of the not-knowing, of the systems we depend on that stretch beyond our individual ken. The more complex shit gets, the more we are engulfed by structures we do not and cannot comprehend, the more anxious we get about our understanding of the world and suck on our soggy, well-gnawed ideological binkies.

This is why explanations such as “intellectual elites ruined everything” are so appealing. They order apparently chaotic events and turn them into familiar stories of good versus evil. The big problem with this particular tale is that it credits nerds with positively super-villainous powers and plans. After we destroy traditional values, we shall repair to our mountain hideaway and turn on the Weather Machine! The mad scientist and the loony prof are hardy pop-culture stereotypes. But they are also alive and well in political life and public discourse, where brains get the blame for social changes that come from a confluence of political and economic causes.

4. Nerds have never run anything real and they live in a candy-coloured dream world.

It seems silly to dispute the existence of schools. We’ve all seen them, and the vast majority of us have attended one or more. Nevertheless, the academic realm is not just excluded from the real world but pitted against it, described as its opposite, as if it does not properly exist. This opposition between school and the real, between learning and doing, does students a great disservice by sending them the mixed message that school is very important, but most of the stuff you learn there is not!

So cram, cheat, pass, and forget. Binge and purge info when required, then advance to the next level and the next until you reach the end screen of graduation and enter regularly scheduled reality, already in progress. It’s okay to game the system when the system is a game. You jump through hoops so employers know you can jump through hoops; nobody gives a shit whether you majored in regular hoops, flaming hoops, or jumping and juggling at the same time.

A number of post-secondary institutions, ranging from accredited universities to substandard diploma mills, try to pitch themselves as education for the “real world,” which perpetuates the notion that campuses are spun of fairy dust and wishes. This split between academia and reality is based on the popular conception of thought and action as polar opposites. Thinking is not the necessary precursor to action, or simply another kind of activity. Instead, thought is the enemy of efficacy and resolve, a perilously querulous anti-productive drag. Doubt is the mark of the quisling. Deliberation is flip-flopping or waffling, failure or unwillingness to heed the call of the heart and the gut. Consideration equals procrastination. Perspiration trumps contemplation.

This sense that activity is real and thinking is artificial is not confined to either side of the political aisle. The right wing’s dismissal of academia as unreal may be more straightforward and full-throated, but the activist left is equally hostile towards tenured stooges who sit in cushy offices writing about poor people’s problems in elite, specialized jargon poor people cannot read.

Others who appoint themselves arbiters of the real do so from a perspective that pleads political neutrality, that speaks for the common sense that politicians and professors of all stripes have abjured. These denizens of the real world, such as business owners, managers, lobbyists, and pundits, are qualified to call for the demise of fields they know nothing about precisely because they know nothing about them. Here ignorance functions as proof of their savvy, a sign that Mr. or Ms. Real World is too sharp to be hornswoggled by some fraudulent, futile major like literature, history, philosophy, or women’s studies.

Occasionally Mr. Real World will cap his argument by insisting that he has read the compleat works of Lofty Classic on his own time, to unwind from the rigours of reality. If he can do some poncy English major’s alleged job on evenings and weekends, it is hardly real work. Culture may well be elevating and all ߝ that’s why he reads Lofty Classic instead of the trash his office mates prefer ߝ but it remains secondary and adjacent to the real world.

We can surmise from such speeches what is not real. The real world is not made of words or art or the past or idealistic theories about equality. Where is this real world and what is it made of? Most people who use the phrase “the real world” are referring to entities like the economy and jobs and money. That makes this particular tenet of reverse snobbery absurd. What newspaper have they been reading throughout the crashes and recessions of the past few years? The Pie-Eyed Optimist Times? The Hooray for Everything Herald Tribune?

Economic turbulence causes real suffering. At the same time, though, it is loopy to deny that vast tracts of modern capitalism are notional, speculative, crazy-brilliant conceptual constructs made up of digital bits and jargon and math that are every bit as imaginary and actual as Hamlet. The word real has been besmirched by prefixes such as “keepin’ it” and suffixes like “-ity TV.” When it appears between the and world, it becomes a rhetorical cudgel, a club to clobber thinking that has no immediate practical value ߝ or at least none that Mr. or Ms. Real World can ascertain.

5. Nerds are living in the past, hung up on defunct ideas.

We often point to our magnificent technological achievements as evidence of our triumph over those benighted primitives who preceded us. I definitely get this vibe from my students. “Why do we need to read this old stuff?” they grouse. It’s, like, old, from the back-in-the-day times when people shat in buckets and were too stupid to invent cool stuff like cellphones. The past is just one long, smelly error until we get to the car, computer, and iPod.

Anything that happened before the students were born is part of the same undifferentiated mass. Sporadically the void spits up costume movies and video games that make youngsters hazily aware of periods such as the toga times and the era of men in silly wigs and skin-tight breeches. Much of their historical knowledge is actually pop-cultural. They recognize evil Nazis and surly, embittered Vietnam vets from Oscar-bait and action movies and games like Call of Duty. But they do not have a very robust sense of when things happened, or what came before them.

Sometimes this ignorance of history expresses itself in the form of backhanded compliments. My English undergrads seem surprised when something old turns out to be interesting. Even though we have much better scary things now, like the Saw franchise, Poe is not boring ߝ or at least not as boring as Macbeth. They cannot quite believe that a rickety claptrap machine like “The Tell-Tale Heart” still functions in spite of its advanced age. And nineteenth-century lit is not really even old in nerd years.

This notion is a testament to the way that technical and economic reasoning elbow out other ways of thinking and dominate student expectations, regardless of their major. If it’s new, it’s more likely to be true and to falsify or negate whatever came before. Reading-intensive subjects such as literature and philosophy, and history itself, suffer under this paradigm, since books and lectures have become antiquated knowledge-delivery systems, consigned to the scrap heap by the predigested info globs of PowerPoint slide shows.

Retention is being outsourced to our prosthetic brains. Why clog your head with tedious facts about the past when you can simply demand an exam review sheet or consult Google or Wikipedia? But there’s something else at work here too. I remember prodding one particularly inert group of undergraduate dial tones thus: “I get the sense that you guys aren’t really interested in what people two hundred years ago thought.” They shrugged. No, not really, was the classroom consensus. What the hell did it have to do with them?

We see a similar shrugging in public life. In a 2009 appearance on HBO’s Real Time with Bill Maher, Republican Meghan McCain declared, “I wouldn’t know; I wasn’t born yet,” when Democratic strategist Paul Begala mentioned the way Reagan had blamed many of his problems on Carter. Another prominent Republican blonde, former White House press secretary Dana Perino, displayed the same whatevs attitude in 2007. In a press conference she dodged a question comparing Bush’s policy to Kennedy’s handling of the Cuban missile crisis. Later, on an NPR quiz show, Perino admitted, “I was panicked a bit because I really don’t know about . . . the Cuban missile crisis . . . It had to do with Cuba and missiles, I’m pretty sure.”

How could she know? Perino is a pup. She was born in 1972, a decade after the 1962 U.S.-Soviet nuclear showdown. It’s not like she was there.

This Young Earth thinking ߝ I am Year Zero! ߝ obliterates history. Meghan McCain and my bored students are essentially Whig historians who do not know what the term Whig history means. They think that they live in the best of all possible worlds and act as though all previous generations were just eejits, fumbling and bumbling their way towards the world we live in now, where everyone knows better. Consequently, they are free to ignore the past. This is sad, and scary, because it means they are like goldfish in a bowl, totally trapped in their own cultural moment, unable to consider it critically or compare it to anything.

6. Nerds are negative nellies: pessimists and player-haters.

The only kind of thinking that sells really well is positive thinking. Unfortunately, this is not thinking at all. For example, The Secret book and DVD both did gangbusters. Those who market The Secret and hawk its law of attraction maintain that “it is the culmination of many centuries of great thinkers, scientists, artists and philosophers.” But I’m quite confident that both Jesus and Leonardo da Vinci had a more challenging and complicated world view than “wishing extra-hard makes it so,” which is what the gurus of The Secret teach their terminally credulous followers.

In a similar vein, many of the most successful mega-churches of recent years retail prosperity gospels, reassuring you that Jesus wants you to be rich, that you are all (to filch a phrase from the troublingly toothy Joel Osteen) “God’s masterpiece.” Never mind that Christ’s instructions to would-be followers are quite explicit, right there in the Bible in red type: yard sale, drain the accounts, give it all away, and get back to me when I know you really mean it. Some of the most popular strains of contemporary Christianity have more to say about getting than giving, casting the Lord as a celestial career coach and concierge and the priest or minister as a ߝ gross portmanteau alert ߝ pastorpreneur.

In a 2008 New York Times op ed, writer Barbara Ehrenreich linked the popularity of New Agey and Christianish positive thinking to the mortgage meltdown. She wrote:

The idea is [that] . . . thinking things, “visualizing”

them ߝ ardently and with concentration ߝ actually

makes them happen. You will be able to pay that

adjustable rate mortgage or, at the other end of

the transaction, turn thousands of bad mortgages

into giga-profits, the reasoning goes, if only you

truly believe that you can.

All that complicated fiscal math was a towering cathedral of logic tottering on a squidgy foundation of feelings. John Maynard Keynes used the term animal spirits to describe the psychological or emotional underpinnings of the market, such as trust and confidence. The Internet and housing bubbles of the past twenty years were periods of overconfidence, of investors getting skunk-drunk on optimism. The crashes and slumps of 2000, 2008, and 2009 were the hangover and morning-after regrets as hot dot-coms and formerly foxy mortgages proved coyote ugly in the merciless morning sun.

Our valorization of belief, our conviction that faith and certitude are virtues, makes the hard work of thinking look pretty dour in comparison. Doubt, skepticism, research, revision, sustained criticism: all of these read as negative, which is a big cultural no-no. Staying positive in spite of the odds, in spite of the facts, is lauded as beneficial to our physical and spiritual health and our capacity to accumulate wealth.

Rational thought has become an excluded middle, squished and muffled by more popular mental modes such as wishing and counting. The practical, money-minded side dismisses thinking as useless navel-gazing, and the wishful one sees it as a major downer, bad thoughts that beckon bad news. Criticizing is just complaining ߝ another object of bipartisan scorn. The right contends that lefty criticisms of markets or the latest war are blame-America-firsting, the mewling and puling of moon-bat losers who are jealous of the successes of suits and soldiers. At the other end of the ideological spectrum from these beefy pragmatists, the flaky and wishful also take a dim view of criticism. They decry negative energy and channelling too much of one’s vital force into corrosive pessimism, lest one poison oneself with hatred.

Even though these two camps appear to have little in common, they both contend that criticism is a wholly personal matter. This is another sign of the decline of reasonable argument; objections are routinely reduced to personal or private squabbles, expressions of petty passions such as jealousy or bitterness. Cons attribute liberal gripes to the individual whinger’s envy or thwarted longing to be the boss of everyone. New Agers exhort us to let go of the unhappy thoughts, as focusing on them will curdle our spirit. In both cases, it is actually all about you: narcissism in the guise of traditional morality or the latest spirituality.

The rugged-individualist and hippy-trippy versions of pro-positive rhetoric both sound awfully retrograde to me. Complaints about complaining, no matter their political slant, all tell us the same thing: Shut up and smile, smile, smile. Keep a gratitude journal, churls. You can thank your executive liege lords for the gift of unpaid overtime and your daily ladlefuls of high-fructose corn gruel.

This complaint ߝ that nerds are negative ߝ is not as goofy or paranoid as the preceding five. Professors can appear negative when they debunk some cherished notion or drop more bad news about our expanding debts, waistlines, and environmental wreckage. But this is one of the most valuable public services nerds provide. Negativity and pessimism are seriously ߝ maybe even dangerously ߝ underrated in North America.

Astute readers have doubtless noticed that these six complaints about nerds contradict each other. But intrepid anti-intellectuals continue to combine them, jumping from charge to charge in the space of a single op ed, speech, sentence, or protest sign. Can someone please let me know if we’re supposed to be lazy losers who can’t hack it in the real world, or corrupters of youth, enemies of capital, and despoilers of democracy? I’d like to adjust my alarm clock accordingly.

This kind of cognitive dissonance is not a problem if you deny that cogitation has value, if you insist that feelings and beliefs are more authentic, more democratic, more trustworthy than ideas. The realm of feelings and beliefs is much more accommodating than reason or history, allowing nerd-bashers to posit a world where intellectuals are simultaneously ineffectual and threatening, buffoons and tempters, failures at life and the covert masters of the world.

Public discourse is a messy mélange of bean-counting, belligerence, and bathos, of number crunching and emoting. We veer from childish wishes (house prices will go up forever!) and hysterical declarations to narrow calculations and reductive analyses. Just watch your local news team as they whipsaw between raw numbers (box-office totals, the GDP, unemployment rates, grim health stat o’ the day) and ploys to jerk tears, fear, and aaws from their audience (house fire, terrorists, child abduction, kid eats ice cream). Numbers and stats bob in a sentimental slop, a swampy slurry of bits of hard data and buckets of mushy manipulation.

Education might look like one of the most centrist issues possible, given that virtually everyone, from wealthy employers to impecunious hippies, agrees that kids should be well-educated. Even the most boorish politician knows better than to run on a platform of fewer, crappier schools and lazier, thicker children. But this nice warm unanimity dissipates quickly when we start talking about why we need good schools, what we mean by good schools, and how we might improve schools.

Arguments about schools and universities, and the way we conduct those arguments, show us that the North American public is quite riven about the life of the mind. We may be dismissive of intellectual life, but we are also exceedingly defensive about it. We are quite anxious about our collective intelligence, constantly fretting about the better students of worse lands supplanting our slack little button-mashing screen junkies.

Again, though, this concern has more to do with money than brains. We’re not worried that our kids will be less well-read than Chinese students. Instead we fear that they will lose out economically and technologically, that the flow of shit work will turn against us and we will be stuck making the poisonous toys and tainted toothpaste, horror of horrors. This is why there are campaigns to get more kids to study the STEM disciplines: science, tech, engineering, and math.

Of course these subjects are important; even Mr. and Ms. Real World will condone them. But it’s foolish and counterproductive to insist that these are the only subjects that really matter and that we should starve the spendthrift arts to save the sciences. First, this ignores the economy of most post-secondary institutions. Science students require a panoply of expensive equipment, which is subsidized by el cheapo arts majors. Pricey instructional tech is slowly creeping into the liberal arts, but the majority of humanities classes require nothing more than a room and a prof and a pile of books.

If that prof is an adjunct ߝ and many in the liberal arts are ߝ the labour costs for the class are less than a single student’s tuition fee. The other twenty-nine, forty-nine, or ninety-nine cheques are free to fund the more important functions and tools of the modern university: new computers for the geeks, feeding the protective blubbery layers of administrators and fundraisers, and splashing out for marketing baubles like snazzier dorms and shinier brochures and websites.

Second, pushing kids who have no interest in a topic to study it as a means to an end guarantees that there will be a goodly number of incompetent, resentful dullards drawing blood and drafting blueprints in the near future. And that’s if they last that long, gritting their teeth and sticking it out till graduation. Nearly half of the people who start a college degree in the U.S.A. never finish it. Steering someone towards a particular major is too little, too late. Cultivating quality nerds is a process that has to start much earlier.

When employers bitch and moan about college grads ߝ can’t read, can’t write, stare blankly when you mention the before-times ߝ their complaints suggest that liberal-artsy skills such as general knowledge and linguistic ability do have some use after all. But a rigorous humanities education also teaches you that there are values other than use, that there is more to human existence than being an employee busy brown-nosing or, better yet, becoming the boss.

Our insistence that everything, especially education, need be useful is wrong-headed. The presumption that everything exists merely for our use is spectacularly ignorant and wantonly destructive, and it’s partly responsible for our ongoing and intertwined economic and environmental difficulties. Moreover, the idea that we are hard-nosed pragmatists, that North Americans venerate usefulness above all things, is utterly at odds with all that crazy shit we’ve just bought and hope to replace and upgrade someday soon, when this whole recession/depression thing finally blows over.

Every university offers a couple of courses that sound kooky and easy to mock in an op ed. But have you been in a Wal-Mart or on Amazon.com lately? How much of that junk is, strictly speaking, useful? It’s pretty hilarious that a culture so devoted to toys and divertissements and status symbols and paraprofessions and pseudo-sciences pitches hissy fits about usefulness when students are wasting their time and money on literature, history, and philosophy. No, it’s far better for them to drop out and pursue a higher calling, like popularizing another cheap piece of plastic guaranteed to delight and serve for mere minutes before it clogs landfills from here to eternity. If they must learn, they should study something really real, something with lots of rote memorizing and right or wrong answers, or the latest trendy, tradesy e-degree. Hell, then they can come up with something truly useful, like a new iFart application.

Throughout this book, I will look at the way our more-money-than-brains mindset affects schools, universities, politics, and pop culture. First, though, a caveat: one of the risks of writing a book like this is the “get off my lawn” tone that creeps into conversations about ignorance and anti-intellectualism. Teachers have bitched about the kids today since Socrates and Saint Augustine bemoaned their feckless charges. Every generation seems to turn declinist when it starts to sag and flag. I would like to avoid this kind of argumentum ad fogeyum.

First, it is unfair to all the great students I’ve had, smart kids of all ages who still care about reading and thinking. Second, I can’t really make a proper declinist argument ߝ one that traces a drop-off from a high point. At the risk of sounding Meghan McCainish, I was born after the periods that other cultural critics cite as periods of intellectual verve and pro-nerd sentiment, such as Hofstader’s early 1960s.

I’m not really interested in pursuing the gap between our particular cultural moment and some wiser age, anyway. It’s not like we can hop in the way-back machine and pretend away developments such as the cable spectrum or the Web, nor would I want to do so. The Internet can be an invaluable resource. There are plenty of intelligent blogs and even more plum dumb books. No medium has the monopoly on bad ideas. Explanations that heap all the blame on text messaging or video games and rap are no better than fulminations against the intellectual elite.

I’m not worried about our failing to live up to the past, though it is a bummer to see so many blithely forget it. This is a really teachery thing to say, but North America’s problem is that it is not living up to its potential. What interests me is the gap between our speeches about schools and the actual school system. What interests me is the gap between North America’s technical sophistication and our ignorance and intolerance of other branches of knowledge.

Pandering to the common folks and their simple ways is the brightly coloured cultural candy-coating on the bitter pill of policies that are anything but populist. Sarah Palin, who has enjoyed a six-figure income for some time, plays working-class heroine by serving moose chili with a side of word salad. She swings the real-world cudgel with indefatigable vim. I’m sure she believes every garbled word, but her white-trash minstrel show in fact equates being working class with being an ignoramus.

Palin’s popularity is a perfect example of the way class has been divorced from wealth and is now wedded to cultural signifiers like religion, rhetoric, and hobbies. People born to trust-fundom and the beneficiaries of the past few bubbles ߝ members of the loftiest economic classes ߝ are not the elite. Rather, the elitists are the ones who sound like they’ve spent too much time in class. A delightful example of this occurred when Lady de Rothschild, a mogul and Clinton fundraiser, decamped to the McCain campaign because she feared that Barack Obama was an elitist. In an interview with CNN’s Wolf Blitzer, she said it was so sad to see the Democratic Party “play the class card,” and then ended by alleging that Blitzer was the elitist, not her.

I reckon that Wolf makes a pretty penny for being on CNN whenever Larry King and Anderson Cooper aren’t. Still, his talking-head salary likely approximates the fresh flower budget for the de Rothschild family estates. But Blitzer is part of the media and de Rothschild, the humble daughter of an aviation company owner in Jersey, just happened to make a pile and marry into a family synonymous with wealth. She is an ordinary self-made millionaire aristocrat who wants to live in an America where anybody ߝ nay, everybody! ߝ can be an ordinary self-made millionaire aristocrat too.

The anti-elitist invective against nerds is laughable when you consider its sources. It is quite a feat of magician’s misdirection, a depressingly effective conjuring of pointy-headed straw men and scarecrows. One of the brutal truths of anti-intellectualism, or at least the version that currently prevails, is that it does not harm intellectuals that much. Oh sure, the name-calling, the snarky op eds, and the budget cuts sting. Job losses and ill-paid part-time gigs ߝ all the rage lately in ostensibly elite fields such as journalism and academia ߝ are difficult to bear. The acquaintances and relatives disappointed that you are not a “real” doctor can also be a swift kick in the ego.

These insults and indignities are flesh wounds compared to the damage that anti-intellectualism inflicts on some of the groups that embrace it ardently, that defend their ignorance as a virtue, be they the too-cool-for-school kids who inadvertently consign themselves to lives of poverty and drudgery or the electorates that must endure policies enacted by plutocratic pols playing just plain folks in order to pick their pockets.

Jeremiads against the nerd elite play on our egalitarian sympathies, but they seem misplaced and daffy given the obeisance we render to other, much more powerful elites. Anti-intellectualism and ignorance have crummy socio-economic consequences, and they do some serious ethical damage too. Institutions such as the free press, democracy, and free markets collapse into farragoes of corruption and incompetence without the scrutiny of an informed populace. Notions such as universal suffrage and inalienable human rights are inextricably linked to the idea of universal human reason, the sense that we are all thinking people who can disagree and debate matters without resorting to fisticuffs or deadly force. When we valorize ignorance and debase reason, we diminish man and the humanity that dwells within him, to bum an old-fashioned phrase from Kant.

From the Hardcover edition.

DON’T NEED NO EDJUMACATION

When I was a bespectacled baby nerd, pudgy, precocious prey for bullies, my parents consoled me with a beautiful lie. Someday, in magical places called college and work, being smart would be cool. I’d have the last laugh while the bullies were slaving away at crummy jobs. My mom and dad said youth was their time to shine, the high point for the popular, truculent lunkheads who mocked spelling bees and science fairs. Their lives would be all downhill after grade 12. Then nerds like me would become doctors and lawyers and maybe even prime minister, and profit from the dimwittedness of our former tormentors. Let ’em have their stupid dances and hockey games, they said. The future belonged to the weird kids who dug microscopes and dictionaries.

This, like many of my parents’ reassuring fibs, was partly true. There was no Santa, but there were plenty of Santas in the malls every December. The power of nerdiness did indeed propel many of my fellow Poindexters into respectable professions. The Poindexters ߝ the pallid, indoorsy, owlish sorts who always got picked last for teams ߝ have become coders and chemists and brokers and communications experts. But the struggle between bullies and nerds certainly did not end, as promised, when we graduated. Nor do nerds always emerge victorious in the contests of adult life. The bullies persevered and proliferated, went online and on TV and the radio, into politics and industry, and found new venues for numerous variations on a familiar theme: Fuck you, four-eyes.

I am not surprised that bullies continue to hate nerds, that the dudes who shove weedy science fair winners into lockers grow up to reject carbon taxes and vote for “strong” leaders. No, what shocks me is the number of self-hating nerds who are willing to pander to the bullies, the countless pundits and politicos who deploy their A-student skills in the service of anti-intellectualism.

This anti-intellectualism is at odds with all our talk about the importance of good schools. North Americans lavish a lot of rhetoric and resources on education. Politicians, pundits, business leaders, and concerned citizens natter on about the need to train workers to stay competitive in a global information economy, where knowledge is power. Post-secondary enrolment has reached record highs and private colleges of varying legitness have sprung up all over North America to cater to our seemingly insatiable hunger for classes. We also spend millions on books, toys, DVDs, video games, and supplements that claim to boost young ߝ or aging ߝ brains.

Never have so many been so schooled! But all this extra education has not turned the majority of North Americans into nerds, or nerdophiles. Our well-intentioned attempts to push and prod every semi-sentient kid through university seem to be backfiring. More people spending money and time on degrees has produced a surprising toxic side effect: more people who hate school ߝ and nerds.

The bachelor’s degree has become a costly high-school diploma, the new middle-class normal. Ergo, higher ed has been demoted to the level of a racket, a swindle, a series of pointless exertions one must complete to get the golden ticket to a good job. Listen to talk radio, watch Fox News, and you’ll learn that nerds are the real bullies. We dastardly bastards run the continent’s most widespread and shameless kid-snatching operation, spiriting people’s beloved offspring away for years so we can make them think (and drink) strange things for our own amusement and enrichment. The con has gone so well that we’ve started hustling suckers of all ages, luring hard-working adults and innocent seniors into our cunning scholastic traps. We extort money, effort, and time from taxpayers, students, and their families by threatening them with the dread spectre of unemployability. Then we teach material our students will never, ever use at work ߝ or anywhere else, for that matter. What do we know-it-alls know about work? It’s not like any of us has ever been there or done any.

Some of the people who spin this spiel are dropouts, such as Glenn Beck and Rush Limbaugh, who matriculated in morning-zoo shows and Top 40 Countdown radio. Beck and Limbaugh present their lack of academic credentials as proof of their moral and intellectual purity. At the same time, they ape the academics they claim to abhor: Limbaugh refers to himself as a professor from the Limbaugh Institute of Advanced Conservative Studies, and Beck scribbles Byzantine charts on a chalkboard as if he’s lecturing undergrads.

Then there are all their fellow-travellers, folks like Ann Coulter and Mark Levin, who have perfectly respectable degrees from elite schools ߝ the very academic institutions they incessantly deride. Politicians such as Dubya and Mitt Romney pull the same act. Pay no attention to my fancy degree or Harvard M.B.A. or the family fortunes that funded my first-class credentials. I’m a commonsensical commoner, a straighttalkin’ shitkicker just like you.

This exceedingly cynical summary of education ߝ that it is a swindle perpetrated by sophists ߝ is not that much of an exaggeration, alas. I’ve seen this view of education, phrased in much more vulgar terms, on many a message board. I’ve encountered more genteel versions of it in political speeches, editorials, and letters to the editor. This dismissive attitude is also evident in other popular phrases. Overeducated is now common parlance. Yet you never hear that someone is overrich or oversexy. Perpetual student is rarely a ringing endorsement of someone’s commitment to “lifelong learning,” to bum a bit of educratic euphemese. When we come across terms such as academic or theoretical in the media, they usually mean “irrelevant” or “imaginary,” mere mental exercises at a remove from the serious business of life. “You think you’re so smart” is never a compliment; the only thing worse than being smart is thinking that you are.

This attitude affects the way students approach university. Many want to get credentials that guarantee them super-awesome careers, but they don’t need no edjumacation. I’ve taught useless liberal-artsy subjects such as English and philosophy for a decade, and some of my students have been quite frank. No offence, Miss, but reading, thinking, and writing are wastes of time and boring as hell. They were never gonna use English . . . even though they had to do precisely that to bitch about its uselessness.

I love teaching, but there are days when I feel like a goddamn cartwright, like a practitioner and proponent of archaic and eccentric arts the kids will not need in the glorious analphabetic future. Sonnets, semicolons, and history might as well be alchemy or phrenology. As long as, like, people can, like, understand you, like, what’s the diff, y’know? Nobody cares about that old stuff. Nobody understands those long words. Nobody ever got hired because they could parse rhyme schemes or pick an argument apart or write a sentence, except for nerds like me, who squander our lives totally overanalyzing every little thing.

It would be a gross generalization to simply say that North Americans are ignorant and anti-intellectual. That would also make a really short book; I could print it in a hundred-point font, illustrate it with pictures of boobs and monster trucks, and then wait to see if it proved itself with boffo sales. It is more accurate to say that North Americans have a love-hate relationship with knowledge. We overestimate the value and reliability of certain uses of intelligence and can be quite disdainful towards mental pursuits that do not result in new stocks, synthetic foodstuffs, pills, or modes of conveyance. If we’re going to endure the insufferable tedium of learning, we do so for one reason: to make the big bucks.

We have, for the past few decades, steadily favoured money over brains. This is not to say that the moneyed are stupid. No, sir! The money-minded would not be so very moneyed if they were not armed with intellect, if they had not invested gross-buckets in their own stable of brains. It takes a surfeit of intellect to create complex financial instruments such as derivatives or to convince people that they need to deodorize, adorn, or alter yet another part of their body. The difference between money and brains is not a matter of how much either side of this divide knows. No, the big difference is the way they see knowledge and why they think intelligence is good. When I say “money,” I mean those who think you learn to earn, that our relation to knowledge is instrumental. When I say “brains,” I mean those who want to learn, who see knowing as an end in itself rather than the means to an end.

The mental work we have been exhorted to pursue is valuable because it is lucrative, not because it is smart. The kinds of thinking we have praised and celebrated, like the innovations of the Internet geek and the heroic entrepreneur or the efficiency of the ruthless CEO, are shrewd, technical ways of assessing the world, interpretations that turn complex states of affairs into calculable measures such as commodity prices and page clicks.

The irony is that our overwhelming emphasis on money, our conviction that markets are the smartest systems of all, has resulted in three recessions and one global market meltdown in the past thirty years. The more-money-than-brains mindset has obvious disadvantages for brains, and the 2008 fiscal collapse suggests that it is not so great for money either. But this crash also gives North Americans a chance to reassess our values and reconsider what we want from our political institutions, education systems, and markets. It is an opportune moment to think about we think about thinking, to examine our domestic intelligence failures and recalibrate the relation between money and brains.

The most obvious example of this shift is Barack Obama’s victory in the 2008 U.S. election, which pundits described as a victory for brains, a Revenge of the Nerds moment after the long, idiotic Bush nightmare. Carlin Romano, a professor and critic, wrote an article for the Chronicle of Higher Education in 2009 that sums up this sentiment nicely: “Philosopher-prez in chief and cosmopolitan in chief. After all this time, you figure, we were entitled to one. It looks as if we’ve got him.”

Obama has made admirable statements about education and his own good old-fashioned liberal arts degree. This is, admittedly, pretty sweet after nearly a decade of presidential pissing in the general direction of fancy book-learnin’. But I think it is way too hasty and optimistic to assume that Obama’s election means smarts are cool again, and that America resolves henceforth to be kinder and gentler to its oft-mocked eggheads.

Saying that Obama’s win marks the end of anti-intellectualism is a lot like saying it means the end of racism. Sure, it’s a good sign, but it’s not like the guy is six feet of antidote. Moreover, Obama’s presidency has inspired a seething right-wing backlash and stupefying coverage of his every snooty foible and flash of hauteur. Jeez, President College can’t even eat right like regular people! When he visited a greasy burger joint for the express purpose of supping with slovenly commoners, he had the audacity to request Dijon, a notoriously French mustard. A sign of Eurosocialist allegiances? Bien sûr.

The post-electoral Republican leadership vacuum was promptly filled by some of the right’s most gleefully proficient nerd-bashers, figures such as Sarah Palin, Glenn Beck, and Rush Limbaugh. All present themselves as mavericks, the only ones brave enough to speak emotive truth to factual power, outsiders marginalized by the uppity chattering classes in Hollywood, New York, and Washington.

These pseudo-populists insist that intellectuals are the real idiots. Ivy League city types think they are so smart, but that only goes to show how deluded and distant from common sense they are. As St. Ronald Reagan said in one of his most famous speeches ߝ 1964’s “A Time for Choosing” ߝ “it’s not that our liberal friends are ignorant. It’s just that they know so much that isn’t so.” The right-wing message is loud and clear: complex matters like climate change and foreign relations and the economy are complex because the elitists and the bureaucrats make them that way, to serve their own agendas and exclude just plain folks from the political process. Have any of these brainiacs ever done something really complicated, like run a Podunk town or make payroll? Didn’t think so!

The most rudimentary business skills or beavering one’s way to bosshood beat teaching or studying at some of the world’s finest universities. Once we’ve established that universities are a joke, a fiendishly elaborate scheme to overcharge people for beer, it is easy to discount any body of facts or ostensible expertise that emanates from them. If expertise in general is fake, a self-serving liberal chimera, then it stands to reason that experts are the biggest frauds of all: empty suits who have nothing to offer but words and dipsy-doodle ideas they expect working people to pay for. The people and the pols become fact-proof, and those who huck information at them align themselves with the patronizing pedants of Team Pantywaist.

This sort of anti-intellectualism is not new. It has been part of American political life ever since Andrew Jackson played the role of Old Hickory. Canadians like to fancy themselves above this sort of pseudo-populist politicking and think that it is the neighbours’ problem. But the Conservative Party’s campaigns against Liberal leaders Stéphane Dion and Michael Ignatieff were just as anti-intellectual, in their own stolid Canadian way, as the invective of the red-meat, redstate crowds at McCain-Palin rallies or anti-tax tea parties.

Professors like Romano, and the mainstream press, have covered Obama’s cosmopolitanism approvingly. They hope it will help ameliorate American relations with the rest of the world. Of course, this is also one of the things that drives Obama’s detractors wild. Drawing huge crowds in Europe, pronouncing Middle Eastern place names correctly, and nabbing a Nobel for nothing are all suspect. Being far’n-friendly is an un-American affectation.

Stephen Harper and company appealed to the Canadian version of this provincial small-mindedness when they ran negative ads that sneered at Ignatieff for describing himself as “horribly cosmopolitan.” His success in and familiarity with foreign lands was not an asset. No, instead he was cheating on Canada, whoring around with the likes of the BBC and Harvard.

I am not a fan of the man, but the Con campaign against him is so frigging brutal it makes me want to like Count Iggy. Consider this gem from their website, Ignatieff.me:

. . . Ignatieff has written next-to-nothing about

the economy ߝ the most pressing issue facing

Canada (and the world) ߝ today. Sure, he’ll talk

your ear off about abstract poetry, nationalism,

the importance of public intellectuals and the

British Royals. But when it comes to the practical

issues that affect real Canadian families ߝ especially

in a recession ߝ he’s invisible.

I love that they lead their shit list with abstract poetry, like Ignatieff is Björk or the ghost of Ezra Pound. The only thing worse than poetry? Abstract poetry, which exists solely to make students feel stupid and professors feel smug. Then there’s nationalism. Nope, can’t see how that relates to governing a nation. (Silly Libs, always thinking this is a country instead of an economy!) The gratuitous monarch-bashing is odd, given that HRH is still smiling gravely from our legal tender; perhaps a right-wing plan is in the works to replace her visage with the image of an oil derrick ߝ our one true queen and head of state.

The Cons and their ad hacks sloppily conflate two kinds of elitism. They mock Ignatieff for living in chi-chi digs in downtown Toronto instead of in the sticks or the burbs, the real Canada. He sips espresso and dips biscotti rather than sucking back double-doubles and Boston creams at the coffee dispensary of the people. Then they attack him for being a brain and a bore, for his sojourns in Yerp and at Harvard. To slam Ignatieff as “cosmopolitan” is typical right-wing nativism, divvying up the citizenry with criteria such as their proximity to livestock and dirt roads and their distance from gay bars and a decent latte. What is hilarious is seeing them mock Ignatieff ’s wealth and privilege. This from Conservatives? They love money, and the people who make lots of it.

Efforts to paint Ignatieff as a tourist, a mere visitor in his own land, play on the idea that intellectuals are always foreigners, outsiders from some theoretical fairyland. We see an even more extreme version of this notion in the Birther conspiracies that allege Obama was not born in America.

The small-town values message ߝ on both sides of the forty-ninth parallel ߝ is clear. Real patriots stay wherever Jesus and their mama’s cooter drop ’em.

This hostility to all things foreign or urban rides shotgun with anti-intellectualism; it’s all part of the same virulent reverse snobbery. Canadians and Americans express their reverse snobbery in slightly different ways, which I will return to later on when we look more closely at politics, in Chapter Five. I’ll also look at some of the differences between righty and lefty anti-intellectualism in that chapter. Republicans and the Alberta wing of Canadian politics have made exceptional contributions in the field of reverse snobbery, but they certainly do not have a monopoly on pseudo-populist poses and ideas. Democrats, Liberals, and the NDP also drop their G’s, chug brewskis, and sing the praises of Joe Six-Pack. They can’t attain high office without pandering to the lowest common denominator, especially when their opponents are spending so much money trying to convince the public that educated candidates are supercilious snobs.

Before we get into different flavours of anti-intellectual invective, let us look at some of the assumptions that disparate nerd-bashers share. Here is a short list of some of the most frequent allegations against the brainy.

1. Nerds are arrogant and think they are better than you.

Nerds do not think they are better than you. Nerds are better than you, in their particular fields, unless you happen to be an even more devoted nerd. This is a fact. However, I must admit, as a good Canadian, that I felt quite dickish typing the phrase “better than you.” North America’s shared egalitarian ideals are admirable, but pseudo-populism exploits those noble notions to level the culture, to raze evidence and argument, to belittle learning so that legitimate scientific research and the myths of creationists represent “both sides of the story.” A pediatrician and Playboy pin-up Jenny McCarthy are equally entitled to pontificate about the potential risks of vaccines. Any chump can go online and tell the world that Shakespeare blows and those dopey books about the sparkly vampire who won’t put out are the BEST EVAR!!1!!.

We have really put the duh in democracy, creating a perverse equality that entitles everyone to speak to every issue, regardless of how much they know about it. We see this on the news all the time. Ask celebrities about foreign policy, quiz the man on the street about the recession, read tweets and emails from the viewers. When a news show does invite experts to speak, producers make sure to get a batch representing “both sides” of the issue and have them squawk over each other for five barely intelligible minutes.

At the same time as the masses were being endowed with the inalienable right to rate everything on the Web or have their 140-character pensées voiced by CNN’s Rick Sanchez, economic inequality increased and social mobility declined. The moneyed elite became more so and the cultural elite became increasingly obsolete, drowned out and washed away by a tsunami of tweets.

Becoming a nerd is hardly a viable route to the top of the social food chain when nerds are the butt of jokes, the official spokespeople for imaginary things and superannuated crud. Anyone taking classics or history for the prestige is either at Oxford or stuck in 1909. The idea that someone would get a liberal arts education to secure a perch above the lowly hordes is a misreading of current cultural conditions, given the well-worn “D’ya want fries with that?” jokes that are your reward for completing a B.A.