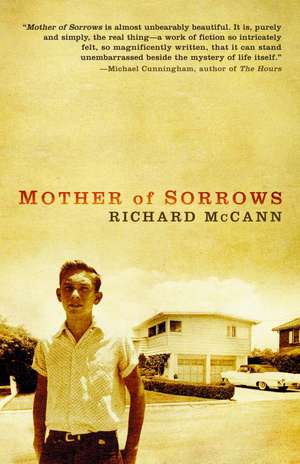

Mother of Sorrows

Autor Richard McCannen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mai 2006 – vârsta de la 14 până la 18 ani

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

Preț: 105.00 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 158

Preț estimativ în valută:

20.09€ • 20.90$ • 16.59£

20.09€ • 20.90$ • 16.59£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 24 martie-07 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400096213

ISBN-10: 1400096219

Pagini: 196

Dimensiuni: 125 x 209 x 14 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

ISBN-10: 1400096219

Pagini: 196

Dimensiuni: 125 x 209 x 14 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Notă biografică

Richard McCann’s work has appeared in The Atlantic Monthly, Esquire, Tin House, and Ploughshares, and in many anthologies, including Best American Essays 2000. He is the author of Ghost Letters, a book of poems. He has received fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, and from the Fulbright and Rockefeller Foundations. He lives in Washington, D.C., where he co-directs the graduate program in creative writing at American University.

Extras

Crêpe de Chine

Each night, after dinner, my father went downstairs to his workbench to build birdhouses, which he fashioned from scraps of wood left over from pine-paneling our basement. He was a connoisseur of birdhouses, my mother said. His favorite was a miniature replica of our ranch house, with a tiny Plexiglas picture window, a red Dutch door, and a shingled roof. It was a labor of love, he said the night he completed it.

My brother, Davis, went to his room, where he listened to Radio Moscow on his shortwave. As for me: I cleared the table.

“Sit with me, son,” my mother said. “Let’s pretend we’re sitting this dance out.”

She told me I was her best friend. She said I had the heart to understand her. She was forty-six. I was nine.

She sat at the table as if she were waiting to be photographed, holding her cigarette aloft. “Have I told you the story of my teapot?” she asked, lifting a Limoges pot from the table. She had been given the teapot by her mother, whom we called Dear—Dear One, Dear Me, Dearest of Us All. Dear had just recently entered a sanatorium for depression, after having given away some of her most cherished possessions. When she died at home a few months later—she’d returned to her deteriorated Brooklyn brownstone, where she slept on a roll-away bed in the basement—my mother found she’d left an unwitnessed will written entirely in rhymed couplets: “I spent as I went / Seeking love and content,” it began.

“No,” I told my mother as I examined the teapot’s gold-rimmed lid, “you haven’t told me about it.”

In fact, by then my mother had already told me about almost everything. But I wanted to hear everything again. What else in Carroll Knolls—our sunstruck subdivision of identical brick houses—could possibly have competed with the stories my mother would summon from her china or her incomplete sterling tea service or the violet Louis Sherry candy box where she kept her dried corsages? I wanted to live within the lull of her voice, soft and regretful, as she resuscitated the long-ago nights of her girlhood, those nights she waited for her parents to come home in taxicabs from parties, those nights they still lived in the largest house on Carroll Street, those nights before her parents’ divorce, before her father started his drinking.

She whispered magic word: crêpe de chine, Sherry Netherlands, Havilland, Stork Club, argent repousée . . .

Night after night she told me her stories.

Night after night I watched her smoke her endless Parliaments, stubbing out the lipstick-stained butts in a crystal ashtray. We sat at the half-cleared table like two deposed aristocrats for whom any word might serve as the switch of a minuterie that briefly lights a long corridor of memory—so long, in fact, the switch must be pressed repeatedly before they arrive at the door to their room.

She said her mother had once danced with the Prince of Wales.

She said her father had shaken hands with FDR and Al Capone.

She said she herself had once looked exactly like Merle Oberon.

To prove it, she showed me photos of herself taken during her first marriage, when she was barely twenty. From every photo she’d torn her ex-husband’s image, so that in most of them she was standing next to a jagged edge, and in some of them a part of her body—where he’d had his hand on her arm, perhaps—was torn away also.

She said life was fifty-fifty with happiness and heartache.

She said that when she was a girl she’d kept a diary in which she’d recorded the plots of her favorite movies.

She said that if I was lucky I too would inherit the gift of gab.

When I was little, she read me Goodnight, Moon. Goodnight, nobody. Goodnight, mush. And goodnight to the old lady whispering “hush.”

But otherwise, she read me no bedtime books. She told me no fairy tales.

Instead she came to my room at night to tell me stories that began like these: Once upon a time, I had a gold brush and comb set. Once upon a time, my parents looked like F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald. Once upon a time, I rode a pony in Central Park. Once upon a time, I had a silver fox coat.

Things she told me, sitting on the edge of my bed at night:

“I was born with a caul. That means I have a sixth sense.”

Or, touching her perfumed wrist to my cheek: “This is called ‘Shalimar.’ ”

Or, faintly humming: “Do you know this tune? Do you know ‘When I Grow Too Old to Dream, I’ll Have You to Remember’?”

Or sometimes when she coughed—her “nervous cough,” her “smoker’s cough”—she said, “One day, after I’m gone, you’ll hear a woman cough like this, and you’ll think she is me.”

From the Hardcover edition.

Each night, after dinner, my father went downstairs to his workbench to build birdhouses, which he fashioned from scraps of wood left over from pine-paneling our basement. He was a connoisseur of birdhouses, my mother said. His favorite was a miniature replica of our ranch house, with a tiny Plexiglas picture window, a red Dutch door, and a shingled roof. It was a labor of love, he said the night he completed it.

My brother, Davis, went to his room, where he listened to Radio Moscow on his shortwave. As for me: I cleared the table.

“Sit with me, son,” my mother said. “Let’s pretend we’re sitting this dance out.”

She told me I was her best friend. She said I had the heart to understand her. She was forty-six. I was nine.

She sat at the table as if she were waiting to be photographed, holding her cigarette aloft. “Have I told you the story of my teapot?” she asked, lifting a Limoges pot from the table. She had been given the teapot by her mother, whom we called Dear—Dear One, Dear Me, Dearest of Us All. Dear had just recently entered a sanatorium for depression, after having given away some of her most cherished possessions. When she died at home a few months later—she’d returned to her deteriorated Brooklyn brownstone, where she slept on a roll-away bed in the basement—my mother found she’d left an unwitnessed will written entirely in rhymed couplets: “I spent as I went / Seeking love and content,” it began.

“No,” I told my mother as I examined the teapot’s gold-rimmed lid, “you haven’t told me about it.”

In fact, by then my mother had already told me about almost everything. But I wanted to hear everything again. What else in Carroll Knolls—our sunstruck subdivision of identical brick houses—could possibly have competed with the stories my mother would summon from her china or her incomplete sterling tea service or the violet Louis Sherry candy box where she kept her dried corsages? I wanted to live within the lull of her voice, soft and regretful, as she resuscitated the long-ago nights of her girlhood, those nights she waited for her parents to come home in taxicabs from parties, those nights they still lived in the largest house on Carroll Street, those nights before her parents’ divorce, before her father started his drinking.

She whispered magic word: crêpe de chine, Sherry Netherlands, Havilland, Stork Club, argent repousée . . .

Night after night she told me her stories.

Night after night I watched her smoke her endless Parliaments, stubbing out the lipstick-stained butts in a crystal ashtray. We sat at the half-cleared table like two deposed aristocrats for whom any word might serve as the switch of a minuterie that briefly lights a long corridor of memory—so long, in fact, the switch must be pressed repeatedly before they arrive at the door to their room.

She said her mother had once danced with the Prince of Wales.

She said her father had shaken hands with FDR and Al Capone.

She said she herself had once looked exactly like Merle Oberon.

To prove it, she showed me photos of herself taken during her first marriage, when she was barely twenty. From every photo she’d torn her ex-husband’s image, so that in most of them she was standing next to a jagged edge, and in some of them a part of her body—where he’d had his hand on her arm, perhaps—was torn away also.

She said life was fifty-fifty with happiness and heartache.

She said that when she was a girl she’d kept a diary in which she’d recorded the plots of her favorite movies.

She said that if I was lucky I too would inherit the gift of gab.

When I was little, she read me Goodnight, Moon. Goodnight, nobody. Goodnight, mush. And goodnight to the old lady whispering “hush.”

But otherwise, she read me no bedtime books. She told me no fairy tales.

Instead she came to my room at night to tell me stories that began like these: Once upon a time, I had a gold brush and comb set. Once upon a time, my parents looked like F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald. Once upon a time, I rode a pony in Central Park. Once upon a time, I had a silver fox coat.

Things she told me, sitting on the edge of my bed at night:

“I was born with a caul. That means I have a sixth sense.”

Or, touching her perfumed wrist to my cheek: “This is called ‘Shalimar.’ ”

Or, faintly humming: “Do you know this tune? Do you know ‘When I Grow Too Old to Dream, I’ll Have You to Remember’?”

Or sometimes when she coughed—her “nervous cough,” her “smoker’s cough”—she said, “One day, after I’m gone, you’ll hear a woman cough like this, and you’ll think she is me.”

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Mother of Sorrows is almost unbearably beautiful. It is, purely and simply, the real thing — a work of fiction so intricately felt, so magnificently written, that it can stand unembarrassed beside the mystery of life itself.”–Michael Cunningham, author of The Hours

“Some of the cleanest, most elegant and unfussy prose I’ve read in ages. . . . [It] is, on one level, a gay coming-of-age narrative, and as such it ranks among the best. . . . But the ruling metaphors here are more universal: concealment and disclosure, assertion and invisibility.” –James Marcus, Los Angeles Times Book Review

“The voice in McCann’s Mother of Sorrows is purely his own — lyrical, melancholy, precise, refined.” –Newsday

“McCann holds such an exquisitely bright light over the landscape of 1950s suburban Maryland and the coming of age of his emotionally fragile, unnamed protagonist who appears in each interlocking story that the resulting book feels almost combustible. . . [His] prose is full of achingly sensual detail and imagery.” –The Washington Post Book World

“Some of the cleanest, most elegant and unfussy prose I’ve read in ages. . . . [It] is, on one level, a gay coming-of-age narrative, and as such it ranks among the best. . . . But the ruling metaphors here are more universal: concealment and disclosure, assertion and invisibility.” –James Marcus, Los Angeles Times Book Review

“The voice in McCann’s Mother of Sorrows is purely his own — lyrical, melancholy, precise, refined.” –Newsday

“McCann holds such an exquisitely bright light over the landscape of 1950s suburban Maryland and the coming of age of his emotionally fragile, unnamed protagonist who appears in each interlocking story that the resulting book feels almost combustible. . . [His] prose is full of achingly sensual detail and imagery.” –The Washington Post Book World

Descriere

"Mother of Sorrows" is a series of portraits of an American family living in the post-World War II suburbs of Washington, D.C.--a world of tract houses, fallout shelters, and sun-struck, treeless lawns, a world from which grief and sexuality have seemingly been banned.

Premii

- Stonewall Book Award Honor Book, 2006

- Lambda Literary Awards Nominee, 2005

- Literary Award Finalist, 2006