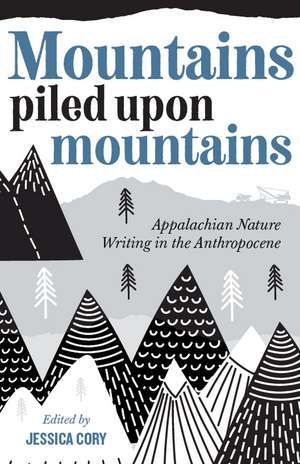

Mountains Piled upon Mountains: Appalachian Nature Writing in the Anthropocene

Editat de Jessica Coryen Limba Engleză Paperback – aug 2019

Mountains Piled upon Mountains features nearly fifty writers from across Appalachia sharing their place-based fiction, literary nonfiction, and poetry. Moving beyond the tradition of transcendental nature writing, much of the work collected here engages current issues facing the region and the planet (such as hydraulic fracturing, water contamination, mountaintop removal, and deforestation), and provides readers with insights on the human-nature relationship in an era of rapid environmental change.

This book includes a mix of new and recent creative work by established and emerging authors. The contributors write about experiences from northern Georgia to upstate New York, invite parallels between a watershed in West Virginia and one in North Carolina, and often emphasize connections between Appalachia and more distant locations. In the pages of Mountains Piled upon Mountains are celebration, mourning, confusion, loneliness, admiration, and other emotions and experiences rooted in place but transcending Appalachia’s boundaries.

This book includes a mix of new and recent creative work by established and emerging authors. The contributors write about experiences from northern Georgia to upstate New York, invite parallels between a watershed in West Virginia and one in North Carolina, and often emphasize connections between Appalachia and more distant locations. In the pages of Mountains Piled upon Mountains are celebration, mourning, confusion, loneliness, admiration, and other emotions and experiences rooted in place but transcending Appalachia’s boundaries.

Preț: 155.45 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 233

Preț estimativ în valută:

29.75€ • 30.94$ • 24.56£

29.75€ • 30.94$ • 24.56£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 25 martie-08 aprilie

Livrare express 08-14 martie pentru 32.43 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781946684905

ISBN-10: 1946684902

Pagini: 360

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.5 kg

Ediția:1st Edition

Editura: West Virginia University Press

Colecția West Virginia University Press

ISBN-10: 1946684902

Pagini: 360

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.5 kg

Ediția:1st Edition

Editura: West Virginia University Press

Colecția West Virginia University Press

Recenzii

“Mountains Piled upon Mountains is a collection of writings that does more than record the observations of Appalachian authors on their environment. It is also a timely call to action: to preserve what might be lost and, most hopefully, what might yet be resurrected. Jessica Cory has given us an important addition to our region’s literature.”

Ron Rash, author of Above the Waterfall

Ron Rash, author of Above the Waterfall

“From the introduction onward, this collection, filled with bright surprises and sharp challenges, engaged my emotions, mind, and senses. Taking in its life-giving poems, heart-piercing stories, and ethically profound essays, night after night I pondered this collection, drank in Appalachia and nature, and felt my sense of wonder and connection renewed.”

Chris Green, director of the Loyal Jones Appalachian Center, Berea College

Chris Green, director of the Loyal Jones Appalachian Center, Berea College

Notă biografică

Jessica Cory teaches in the English department at Western Carolina University. She grew up in southeastern Ohio, and her work has been published in ellipsis…, A Poetry Congeries, and other journals.

Extras

Introduction

Let’s be clear: Appalachian nature writing is nothing new. Recently a colleague, the wonderful Dr. Mae Miller Claxton, declared that “every Appalachian writer is an environmentalist”—and she’s right. With roots in the oral histories of the indigenous peoples who resided in these mountains and continuing on with the explorers and naturalists who found themselves in the region, nature writing has a rich and developed history in Appalachia. William Bartram’s Travels is often credited as the seminal work of Appalachian nature writing, and Horace Kephart notes in Our Southern Highlanders that “William Bartram of Philadelphia came plant-hunting into the mountains of western Carolina and spread their fame to the world”; he goes on to refer to Bartram as “the botanist who discovered this Eden.” Kephart’s admiration of Bartram struck a chord, too, with Edward Abbey, who is best known for his musings on desert life. In one of Abbey’s lesser-known works, his “Natural and Human History” essay in Eliot Porter’s Appalachian Wilderness: The Great Smoky Mountains, Abbey quotes Kephart’s praises and expands on the ideas first put forth by these pioneers of the genre. Mountains Piled upon Mountains continues to develop this understanding of the importance of Appalachian nature and human engagement with it, as well as further examines the definition of “the nature focused text” as “a cultural-literary text.”1 The popularization of the term Anthropocene over the last decade to describe our new epoch as one marked by human influence only serves to further these connections between nature and culture and, as such, the texts that spring from this relationship.2 By bringing together both well-known and emerging Appalachian writers to explore Appalachian nature in the Anthropocene, this collection shows that nature writing in and of the region continues to flourish and evolve centuries after Bartram’s legacy and the continuation of human involvement in the natural world.

Certainly, collections of nature writing that focus on particular areas of Appalachia exist. Excellent examples include George Ellison’s two-volume High Vistas, which examines western North Carolina and the Great Smokies; The Height of Our Mountains by Michael Branch and Daniel Philippon, covering the Blue Ridge Mountains and Shenandoah Valley of Virginia; and Neil Carpathios’s Every River on Earth: Writing from Appalachian Ohio. However, as Heike Shaefer notes, nature writing is often a regionalist endeavor.3 Consequently, these collections, while helpful in understanding and appreciating the human engagement with Appalachian nature, offer a limited scope that diminishes the similarities of Appalachian areas and reduces the broader voice that the region as a whole can uplift, adding to the larger conversation of Appalachia and its natural (and, in some cases, man-made) environments. Regional place-based writing certainly provides those familiar and unfamiliar with the area with an “ecologically informed [redefinition] of human identity and cultural practices.”4 However, it’s my hope that a compilation of nature writing representative of the entire Appalachian region provides readers with a more comprehensive scope and understanding of Appalachian nature, culture, and people.

When selecting the works to be included in this collection, I considered the public perception of Appalachia, particularly by those who may live and work outside of the region. Often there is the misconception that Appalachian authors (and, indeed, Appalachia itself) are simply rural, white, and male. Though the latter part of that assumption has begun to fade with the fame of Kathryn Stripling Byer, Ann Pancake, and others, the perception—and to an extent, the reality of Appalachian literature being largely white—still persists. As Althea Webb reveals, “Appalachia has always had a racially and ethnically diverse population that has been significant and influential. Migration and mobility has shifted patterns of diversity within sub-regions and particular counties, but many areas recall traditions of inclusive collaboration unlikely to have taken hold outside the mountains.”5 Fortunately, there has been a recent effort to include and incorporate Affrilachian and Native American authors in the study of Appalachian literature. As these authors help to create the ecological history of the region, it’s important that we consider their works with the same, if not more, appreciation with which we approach more demographically homogenous Appalachian texts.

By having a better understanding of the history of nature writing in Appalachia and by gaining insight into the motives of writers who engage with nature, we’re encouraged to analyze our own ways of interacting with the natural world, especially as human engagement has become the marker for our current epoch. Are we activists fighting in the war against mountaintop removal? Do we shop at our local farmer’s market? Perhaps some of us garden or raise animals for meat. Or maybe we enjoy sipping our coffee on the front porch and watching the hummingbirds flit in and out, sipping their sugar water from the red glass ornament hanging from the hook beside the butterfly bush. All of these methods of interaction are important, as they shape our worldview and impact our human experience.

As evidenced in the works of Kephart, Bartram, Abbey, and many others, nature writing is almost always created with one or more of a few select purposes. These objectives include to recount an event tied inextricably to the natural world, to contemplate or appreciate a facet of one’s natural environment, to express outrage and raise awareness of environmental destruction, to encourage others to preserve or protect part of the natural world, to explore potential benefits and drawbacks as humans continue to evolve within and beside nature, and, finally, to celebrate the wonders and bounty that nature provides.

Meditation on aspects of the natural world, as the section on contemplation evidences, whether in simply appreciating nature’s beauty or being enthralled by its capabilities, can have an amazingly therapeutic effect on both the meditator and the reader. Many Appalachian writers throughout the ages have contemplated either the infinitesimal or the overwhelming. From Annie Dillard who in A Pilgrim at Tinker Creek describes the minute evolution of caterpillar eggs to Barbara Kingsolver who rhapsodizes on the positive effects of local food production on the region’s landscape and economy in Animal, Vegetable, Miracle: A Year of Food Life, Appalachian writers are hoping to create in their readers a similar contemplation or at least to help readers see nature’s relevance. Perhaps changing the mind of a single reader is all it will take to change the larger man-versus-nature narrative.

In Taylor Brown’s “Harper,” we see a young man’s contemplation and engagement with nature play a pivotal role in his coming of age and understanding. A similar importance of contemplation as part of one’s journey can be found in Jeanne Larsen’s “At Goshen Pass, the Search” wherein entering nature without the extraneous “necessities” of modern life is “like . . . going into rehab.” Echoing the role of nature on one’s journey, David Young and Lisa Ezzard ponder in their works how nature and their experiences within it affect their thoughts and thought patterns, and how nature shapes the people we become. Continuing the inward focus that contemplation often takes, Scott Honeycutt and Felicia Mitchell use nature as a touchstone to contemplate human impermanence, as Mitchell muses on a “name I’ll forget / before I forget why I wanted to remember it all” and Honeycutt reflects on “the silence of hills and returning to / nothing that beauty of lost hours.” The internal dialogue that the natural world facilitates can be pivotal not only to writers but also to the rest of us as we struggle to fit in moments of self-reflection amid our busy schedules and demanding societal pace.

It’s important to note, however, that nature-based contemplation isn’t all inward-focused navel-gazing; often an aspect of nature will spark a curiosity that puts nature itself in the place of the role of the protagonist. G. C. Waldrep and Stephen Cushman, for example, channel plants in their poems “White Trillium” and “Green Zebra,” wherein the tomato realizes it “had evaded human improvement.” Gene Hyde’s “Shooting Rivers and Smoldering Churches: Fire and Rain in Appalachia” examines the role of water, specifically rainfall, in the region, as does John Robinson’s “Evening Storm.” This placement of nature at the forefront of contemplation, rather than simply the medium, allows readers to notice the ways in which their perceptions of nature are shaped by human interaction.

Recounting an experience is another common way for writers to engage with nature and help their readers connect to a particular place. Many times, we find something in nature that an experience or memory is tied to. Perhaps it’s berry picking with an older cousin or eating one of grandpa’s tomatoes, fresh off the vine. Maybe it’s the wafting scent of lilac or honeysuckle that reminds us of our childhoods, playing barefoot with the cool, slick blades of grass sliding between our toes. By describing a particular setting, writers are able to reenter their experiences and take the reader with them, as we see in the section that focuses on this purpose. In Sarah Beth Childers’s “Beaver Pond,” we see the narrator recounting her trips as a young girl to Beaver Pond with her father and uncle, a place she returns to in order to find solace and remember her uncle after his passing, but all that’s left are “a few dried-out sticks, gnawed to sharp white points” with no pond in sight. These themes of recollection and loss can also be found in Jesse Graves’s “Our Mother,” whose speaker is reminded of his loss by the “blackberry-scented” air. In Ellen Perry’s “Joni and Jesus,” we see the changing seasons parallel Joni’s relationship with her brother, Jackson, and her reflection on the loss of that relationship. Finally, Scott Honeycutt’s tragicomic “Reverie with Chestnut Trees” paints a portrait of a deceased loved one encountering the changed landscape of modern-day Appalachia. By using nature to channel the memories of their loved ones, these writers are able to maintain a sense of connection to their beloveds despite their physical absence.

However, recounting doesn’t have to involve a physical loss. In Bill King’s “Going for Tadpoles in My Son’s 18th Year,” the speaker not only recounts an experience that he shares with his son but also rhapsodizes on how quickly childhood fades into adulthood. M. W. Smith also attains a sense of nostalgia in “Spring Box,” which recalls a simpler time when “Drinking, tying flies, laughing” reigned, but now remain “only a vague narrative.” These writers show that by fully immersing themselves in the experiences and reveries provided by the natural world, they are honoring not only nature but also themselves.

While meaningful contemplation and engagement with nature can be enjoyable for its own sake, it can also lead to the discovery of larger issues, exemplified in the section on destruction. In modern-day Appalachia, rife with hydraulic fracturing (or “fracking”), injection wells, logging, mountaintop removal, contaminated water, and continued underground and strip mining, the exploitation of Appalachia and those who call it home is palpable, as is the destruction such practices bring to the natural world. As many residents and nature lovers try to resist, fight, or perhaps even cope with the damage being perpetrated on their landscapes, writing is often a tool that they use, as Susan Deer Cloud notes in “Mountaintops, Appalachia.” In addition to Deer Cloud, this collection also showcases many other writers taking to task the destructive measures of energy companies and other corporations. Julia Spicher Kasdorf’s speaker narrowly avoids confrontation with energy sector workers in “American Bittersweet,” and Lisa Hayes-Minney discusses the dangerous side effects of fracking, which companies continually dispute. Madison Jones in “At Heaven’s Dirty Riverbank” echoes Hayes-Minney’s concern about the impact of environmental peril. In order to halt the environmental degradation taking place in Appalachia, additional action is necessary, and it’s clear that many writers hope that their works can be a catalyst for such action by bringing attention to these exploitative systems and measures.

Sometimes larger-scale destructions, such as long-term effects or systemic destabilization, occur long after the immediate danger appears to have ceased. One classic example of destruction can be found in Kathryn Stripling Byer’s “Just before Dawn,” based on the debris flow, or mudslide, that occurred in Maggie Valley, North Carolina, in 2003 when a woman died as mud engulfed her home. Heavy rains and a faulty retaining wall were blamed for the event. Debris flows can often be expedited by human infrastructure or interference. As we are shown in Ben Burgholzer’s “Border Waters,” Julia Spicher Kasdorf’s “They Call It a Strip Job,” and Byer’s “On Waterrock Knob,” exploitative land practices can result in irrecoverable damage to the environment and to those who depend on it for survival. In addition to destruction of the land to gain access to natural resources, Heather Ransom’s “Stockholm State: A History” exposes how the systems at work in the region can damage the region’s own citizens.

Clean drinking water and uncontaminated air are a necessity for everyone, including those with occupations that endanger the very land they inhabit. While it’s easy to associate destruction with exploitation, the other side of the argument brings about the issue of destruction of one’s way of life. In Ed Davis’s “Making Paradise,” the locals are terrified of losing their livelihood as loggers and paper manufacturing workers. Destruction can also be so simple that it becomes commonplace, as Michael McFee takes notice of in “Devil’s Rope.” It’s important to note that even destruction that appears to be nominal can wind up having a serious impact, and often the impact isn’t felt until intervention becomes a complicated and arduous matter.

When writing about environmental destruction, many authors choose to champion preservation. Preservation, in one sense, involves taking care of the environment rather than defending it from those who wish to exploit it for their own means. In this section, Brent Martin brings our attention to the history of conservationism and preservation in “Appalachian Wildness and the Death of the Sublime” by noting a historical issue that continues in many parts of Appalachia today: “Urban and industrial America called for conservation and preservation, while rural Americans, as well as corporate America, saw the vast expanse of publicly owned land as either a common space to be utilized or as a natural resource base to be exploited for profit.” Laura Henry-Stone discusses preservation in her essay, “Hemlocks, Adelgids, and People: Ecological Learning from an Appalachian Triad,” showing how even small-scale actions can make an impact.

Preservation in another sense can be seen as an action taken to avoid erasure of memories, customs, and histories. In this view of preservation, Gail Tyson’s “Man Talk” and “Frog and Tadpole,” and Julia Spicher Kasdorf’s “Home Farm,” portray the struggle of preserving one’s way of life. In these poems, we see how family and community members uphold traditions. Such writing of preservation has a lengthy history in the region. Much of Appalachian culture, including the indigenous cultures of the Ani’yunwi’ya (Cherokee), Shawanwa (Shawnee), Coyaha (Yuchi), Chikasha (Chickasaw), Lenape (Delaware), and Mvskoke Etvlwv (Muscogee/Creek), was, and still is, passed down through oral tradition. Unfortunately, as families and lineages are separated by forced removal, diaspora, migration, or simply death, these oral histories are not always passed on. Recording, by writing or other means, allows the continued existence of these histories and provides a way for future generations to learn about the cultural heritages of the Appalachian region. Emma Bell Miles’s The Spirit of the Mountains is one such example of writing to preserve the mountain culture, as are the narratives of Sarah Gudger, Dan Bogie, Harriet Mason, and many other former slaves, whose recorded experiences help add to our historical and cultural knowledge of the Appalachian region. In my essay “Uprooted,” I both preserve what I know about my family’s history and argue that the tradition of farming in Appalachia needs to be preserved and handed down as well. Preserving these stories of Appalachian individuals and communities allows us to understand and honor the full range of Appalachian experience.

While some community members may band together to preserve their livelihoods, other Appalachians may feel the need to protect themselves and their landscapes from these community members. Protection in Appalachia can look very different depending on which side you’re on. Since this collection focuses on nature, understandably the vast majority of works in this section center on protecting the natural world from the man-made forces that jeopardize it. In Katie Fallon’s “Forest Disturbance,” the vulnerable forest is put at risk by privately held mineral rights below its humus. In George Hovis’s “Your Mee-Maw vs. CXP Oil & Gas, LLC,” a grandmother takes a stand to protect her land from the effects of fracking. Rick Van Noy’s “Take in the Waters: On the Birthplace of Rivers, West Virginia” and Kathryn Stripling Byer’s “Waynesville Watershed” remind us of Wilma Dykeman’s warning in The French Broad: “Water is a living thing; it is life itself,” and if the water quality suffers, “all the network of creatures that live by water, including man himself” are in danger. Thomas Rain Crowe also echoes Dykeman’s sentiment that “if the fundamental ingredients of living [are] sounds and good, the furbelows [can] be done without.” In his essay, “In Praise of Wilderness: Getting What You Give Up,” Crowe suggests that in protecting the land, we are truly protecting ourselves. What these writers convey is a theme often found in Appalachian literature: that to survive on the land, one must protect it.

To close the section, Rosemary Royston takes us in a new direction: protecting oneself and one’s family by natural (and, save the death of a blackbird, largely nonviolent) folkloric methods. These poems and the suggested protection methods are based on Royston’s recent research from “Edain McCoy’s Mountain Magick: Folk Wisdom from the Heart of Appalachia, along with stories shared with [her] by those who’ve lived the majority of their lives in Appalachia.” Her poems both remind us of the region’s cultural heritage as well as how the region is ever evolving.

Evolving views on folkloric protection methods are just one way Appalachia has changed over the centuries. However, what comes to mind more immediately than myths when transformation and Appalachia are discussed is the industrial presence in the region. As industry progresses and changes the landscape as well as the way of life for many residents, uncertainty and anxiety creep in and are often expressed in the essays and poems in this section focusing on Appalachia’s evolution. The discussion of nature versus industry, or what some may tout as “progress,” particularly in Appalachia, has long been a source of fuel for writers. In an 1899 issue of McClure’s Magazine, Sarah Barnwell Elliott contributed a piece called “Progress,” centering on the feared changes of a widespread railroad industry. Concerns about change, whether largely unfounded or based on science and economics, continue today in the nature writing of Appalachia.

This section begins with Ann Pancake’s “Letter to West Virginia, November 2016,” exposing us to the contradictions and evolutions both the land and its people endure and the hopeful idea “that tearing down clears an emptiness for opportunity.” Writer doris diosa davenport’s “cycles and (scrambled) seasons” echoes this complex and often cyclic evolution of both nature and our own lives. In “High Water,” Mark Powell presents the transformation of numerous characters against a natural world that moves from foreground to background and back again in a sort of ethereal evolution all its own. Stephen Cushman’s “Love in the Age of Inattention” and Felicia Mitchell’s “Towhee” bring to light the effects of technology not only on human relationships but also on human relationships with nature. As Mitchell notes, “I am complicit here / . . . Without thinking, wasting electricity / I can disturb the universe.” While the effects of humans on nature cannot be negated, Libby Falk Jones, Larry D. Thacker, and Jesse Graves focus instead on the evolution of nature itself, particularly the signs of seasonal transformation, such as the “Bush budding white, crocus unfolding” in Jones’s “February Springtime in the Mountains” or the way in which “the first cold nights have curled / the edges of forest-floor ginger” in Graves’s “October Woods.” In many ways, these seasonal transitions shape our everyday lives.

These changes in season are more than just beautiful; they’re often reasons to celebrate. Just think of the way the natural world plays a role in many of our own celebrations. Many of us marvel at the first snow of the season or carve pumpkins for our front porches in late autumn. We spend time swimming in lakes and rivers at summertime get-togethers and hunt morels in the late spring. As prominent a role as nature plays, it’s no wonder artists and writers invoke its beauty in celebration. In this section focusing on such celebration, Jane Harrington’s “Settling” revels in the relief Cornelius is able to experience when met with opportunity in a difficult landscape. “How to Avoid the Widow Maker” by Jim Minick may not seem to be celebratory at first read—the speaker is felling trees, after all. However, triumphing over a widow maker certainly is celebratory, as knowledge and skill aren’t always enough to avoid a falling tree. These examples display the harmony that can arise when humans and nature are truly integrated.

The natural world can often remind us to celebrate those who mean the most to us as well. In Jeremy Michael Reed’s “In Tennessee I Found a Firefly,” the speaker’s time in the yard, alone except for fireflies, causes him to reflect on the love he shares with his partner: “the way love bends / over time, the way a hushed phrase / creates flash of lightning.” M. W. Smith’s speaker is also reminded to celebrate his loved one—a deceased grandfather—by the “eight hundred acres” this “unofficial town mayor” left behind. Whether it’s a hiking trail that we’ve trekked with a spouse or a fishing hole where we caught our first trout, nature is full of small reminders to honor our loved ones and experiences.

While the themes of honor and respect for nature are present in Susan Deer Cloud’s “Clingmans Dome Before Thanksgiving” and Lisa Ezzard’s “Wine Is the Color of Blood,” the respect is very much earned, as the speakers wrangle with the natural world. By juxtaposing a celebratory tone with surprisingly intimidating imagery, Deer Cloud’s “Spanish moss hanging like lynched ghosts / in the mists” and Ezzard’s “I spit and feel the sharp edge on the palate” may seem at odds initially. This combination, however, makes the celebration seem much more deserved, hard won. When Deer Cloud’s “lovers” are “lit to bedazzlement” among “frozen trees, broken weeds, limp grasses,” the reader knows that a journey through the natural world can be just as difficult as many of the other journeys we face, but just like the more mundane sojourns, the view at the end is often worth it. These pieces also serve as reminders that reasons to celebrate are perhaps not always easy to identify; it’s by excavating through the “gnarled vines” that we find true joy.

In whole, this collection represents a wide swath of Appalachian engagement with nature during a time of great environmental change. The natural world in Appalachia is incredibly significant for a variety of reasons—its obvious beauty, its ample biodiversity, and its struggle, the latter of which is indelibly tied to the Anthropocene. On a more national or global scale, the immense exploitation and degradation of the Appalachian landscape is both cause for concern and reason for hope: if people here can learn to live in balance and harmony with nature, then it’s possible anywhere. The writers in this collection seem to share the goal that, while it may not be easy, such a future is possible. While the spectrum and experiences can vary widely, as do the writers’ understandings and encounters with the natural world, they also implore us to explore the role nature plays in our own lives and communities and to deepen those connections in light of what the Anthropocene might mean for ourselves, our communities, and our world.

Let’s be clear: Appalachian nature writing is nothing new. Recently a colleague, the wonderful Dr. Mae Miller Claxton, declared that “every Appalachian writer is an environmentalist”—and she’s right. With roots in the oral histories of the indigenous peoples who resided in these mountains and continuing on with the explorers and naturalists who found themselves in the region, nature writing has a rich and developed history in Appalachia. William Bartram’s Travels is often credited as the seminal work of Appalachian nature writing, and Horace Kephart notes in Our Southern Highlanders that “William Bartram of Philadelphia came plant-hunting into the mountains of western Carolina and spread their fame to the world”; he goes on to refer to Bartram as “the botanist who discovered this Eden.” Kephart’s admiration of Bartram struck a chord, too, with Edward Abbey, who is best known for his musings on desert life. In one of Abbey’s lesser-known works, his “Natural and Human History” essay in Eliot Porter’s Appalachian Wilderness: The Great Smoky Mountains, Abbey quotes Kephart’s praises and expands on the ideas first put forth by these pioneers of the genre. Mountains Piled upon Mountains continues to develop this understanding of the importance of Appalachian nature and human engagement with it, as well as further examines the definition of “the nature focused text” as “a cultural-literary text.”1 The popularization of the term Anthropocene over the last decade to describe our new epoch as one marked by human influence only serves to further these connections between nature and culture and, as such, the texts that spring from this relationship.2 By bringing together both well-known and emerging Appalachian writers to explore Appalachian nature in the Anthropocene, this collection shows that nature writing in and of the region continues to flourish and evolve centuries after Bartram’s legacy and the continuation of human involvement in the natural world.

Certainly, collections of nature writing that focus on particular areas of Appalachia exist. Excellent examples include George Ellison’s two-volume High Vistas, which examines western North Carolina and the Great Smokies; The Height of Our Mountains by Michael Branch and Daniel Philippon, covering the Blue Ridge Mountains and Shenandoah Valley of Virginia; and Neil Carpathios’s Every River on Earth: Writing from Appalachian Ohio. However, as Heike Shaefer notes, nature writing is often a regionalist endeavor.3 Consequently, these collections, while helpful in understanding and appreciating the human engagement with Appalachian nature, offer a limited scope that diminishes the similarities of Appalachian areas and reduces the broader voice that the region as a whole can uplift, adding to the larger conversation of Appalachia and its natural (and, in some cases, man-made) environments. Regional place-based writing certainly provides those familiar and unfamiliar with the area with an “ecologically informed [redefinition] of human identity and cultural practices.”4 However, it’s my hope that a compilation of nature writing representative of the entire Appalachian region provides readers with a more comprehensive scope and understanding of Appalachian nature, culture, and people.

When selecting the works to be included in this collection, I considered the public perception of Appalachia, particularly by those who may live and work outside of the region. Often there is the misconception that Appalachian authors (and, indeed, Appalachia itself) are simply rural, white, and male. Though the latter part of that assumption has begun to fade with the fame of Kathryn Stripling Byer, Ann Pancake, and others, the perception—and to an extent, the reality of Appalachian literature being largely white—still persists. As Althea Webb reveals, “Appalachia has always had a racially and ethnically diverse population that has been significant and influential. Migration and mobility has shifted patterns of diversity within sub-regions and particular counties, but many areas recall traditions of inclusive collaboration unlikely to have taken hold outside the mountains.”5 Fortunately, there has been a recent effort to include and incorporate Affrilachian and Native American authors in the study of Appalachian literature. As these authors help to create the ecological history of the region, it’s important that we consider their works with the same, if not more, appreciation with which we approach more demographically homogenous Appalachian texts.

By having a better understanding of the history of nature writing in Appalachia and by gaining insight into the motives of writers who engage with nature, we’re encouraged to analyze our own ways of interacting with the natural world, especially as human engagement has become the marker for our current epoch. Are we activists fighting in the war against mountaintop removal? Do we shop at our local farmer’s market? Perhaps some of us garden or raise animals for meat. Or maybe we enjoy sipping our coffee on the front porch and watching the hummingbirds flit in and out, sipping their sugar water from the red glass ornament hanging from the hook beside the butterfly bush. All of these methods of interaction are important, as they shape our worldview and impact our human experience.

As evidenced in the works of Kephart, Bartram, Abbey, and many others, nature writing is almost always created with one or more of a few select purposes. These objectives include to recount an event tied inextricably to the natural world, to contemplate or appreciate a facet of one’s natural environment, to express outrage and raise awareness of environmental destruction, to encourage others to preserve or protect part of the natural world, to explore potential benefits and drawbacks as humans continue to evolve within and beside nature, and, finally, to celebrate the wonders and bounty that nature provides.

Meditation on aspects of the natural world, as the section on contemplation evidences, whether in simply appreciating nature’s beauty or being enthralled by its capabilities, can have an amazingly therapeutic effect on both the meditator and the reader. Many Appalachian writers throughout the ages have contemplated either the infinitesimal or the overwhelming. From Annie Dillard who in A Pilgrim at Tinker Creek describes the minute evolution of caterpillar eggs to Barbara Kingsolver who rhapsodizes on the positive effects of local food production on the region’s landscape and economy in Animal, Vegetable, Miracle: A Year of Food Life, Appalachian writers are hoping to create in their readers a similar contemplation or at least to help readers see nature’s relevance. Perhaps changing the mind of a single reader is all it will take to change the larger man-versus-nature narrative.

In Taylor Brown’s “Harper,” we see a young man’s contemplation and engagement with nature play a pivotal role in his coming of age and understanding. A similar importance of contemplation as part of one’s journey can be found in Jeanne Larsen’s “At Goshen Pass, the Search” wherein entering nature without the extraneous “necessities” of modern life is “like . . . going into rehab.” Echoing the role of nature on one’s journey, David Young and Lisa Ezzard ponder in their works how nature and their experiences within it affect their thoughts and thought patterns, and how nature shapes the people we become. Continuing the inward focus that contemplation often takes, Scott Honeycutt and Felicia Mitchell use nature as a touchstone to contemplate human impermanence, as Mitchell muses on a “name I’ll forget / before I forget why I wanted to remember it all” and Honeycutt reflects on “the silence of hills and returning to / nothing that beauty of lost hours.” The internal dialogue that the natural world facilitates can be pivotal not only to writers but also to the rest of us as we struggle to fit in moments of self-reflection amid our busy schedules and demanding societal pace.

It’s important to note, however, that nature-based contemplation isn’t all inward-focused navel-gazing; often an aspect of nature will spark a curiosity that puts nature itself in the place of the role of the protagonist. G. C. Waldrep and Stephen Cushman, for example, channel plants in their poems “White Trillium” and “Green Zebra,” wherein the tomato realizes it “had evaded human improvement.” Gene Hyde’s “Shooting Rivers and Smoldering Churches: Fire and Rain in Appalachia” examines the role of water, specifically rainfall, in the region, as does John Robinson’s “Evening Storm.” This placement of nature at the forefront of contemplation, rather than simply the medium, allows readers to notice the ways in which their perceptions of nature are shaped by human interaction.

Recounting an experience is another common way for writers to engage with nature and help their readers connect to a particular place. Many times, we find something in nature that an experience or memory is tied to. Perhaps it’s berry picking with an older cousin or eating one of grandpa’s tomatoes, fresh off the vine. Maybe it’s the wafting scent of lilac or honeysuckle that reminds us of our childhoods, playing barefoot with the cool, slick blades of grass sliding between our toes. By describing a particular setting, writers are able to reenter their experiences and take the reader with them, as we see in the section that focuses on this purpose. In Sarah Beth Childers’s “Beaver Pond,” we see the narrator recounting her trips as a young girl to Beaver Pond with her father and uncle, a place she returns to in order to find solace and remember her uncle after his passing, but all that’s left are “a few dried-out sticks, gnawed to sharp white points” with no pond in sight. These themes of recollection and loss can also be found in Jesse Graves’s “Our Mother,” whose speaker is reminded of his loss by the “blackberry-scented” air. In Ellen Perry’s “Joni and Jesus,” we see the changing seasons parallel Joni’s relationship with her brother, Jackson, and her reflection on the loss of that relationship. Finally, Scott Honeycutt’s tragicomic “Reverie with Chestnut Trees” paints a portrait of a deceased loved one encountering the changed landscape of modern-day Appalachia. By using nature to channel the memories of their loved ones, these writers are able to maintain a sense of connection to their beloveds despite their physical absence.

However, recounting doesn’t have to involve a physical loss. In Bill King’s “Going for Tadpoles in My Son’s 18th Year,” the speaker not only recounts an experience that he shares with his son but also rhapsodizes on how quickly childhood fades into adulthood. M. W. Smith also attains a sense of nostalgia in “Spring Box,” which recalls a simpler time when “Drinking, tying flies, laughing” reigned, but now remain “only a vague narrative.” These writers show that by fully immersing themselves in the experiences and reveries provided by the natural world, they are honoring not only nature but also themselves.

While meaningful contemplation and engagement with nature can be enjoyable for its own sake, it can also lead to the discovery of larger issues, exemplified in the section on destruction. In modern-day Appalachia, rife with hydraulic fracturing (or “fracking”), injection wells, logging, mountaintop removal, contaminated water, and continued underground and strip mining, the exploitation of Appalachia and those who call it home is palpable, as is the destruction such practices bring to the natural world. As many residents and nature lovers try to resist, fight, or perhaps even cope with the damage being perpetrated on their landscapes, writing is often a tool that they use, as Susan Deer Cloud notes in “Mountaintops, Appalachia.” In addition to Deer Cloud, this collection also showcases many other writers taking to task the destructive measures of energy companies and other corporations. Julia Spicher Kasdorf’s speaker narrowly avoids confrontation with energy sector workers in “American Bittersweet,” and Lisa Hayes-Minney discusses the dangerous side effects of fracking, which companies continually dispute. Madison Jones in “At Heaven’s Dirty Riverbank” echoes Hayes-Minney’s concern about the impact of environmental peril. In order to halt the environmental degradation taking place in Appalachia, additional action is necessary, and it’s clear that many writers hope that their works can be a catalyst for such action by bringing attention to these exploitative systems and measures.

Sometimes larger-scale destructions, such as long-term effects or systemic destabilization, occur long after the immediate danger appears to have ceased. One classic example of destruction can be found in Kathryn Stripling Byer’s “Just before Dawn,” based on the debris flow, or mudslide, that occurred in Maggie Valley, North Carolina, in 2003 when a woman died as mud engulfed her home. Heavy rains and a faulty retaining wall were blamed for the event. Debris flows can often be expedited by human infrastructure or interference. As we are shown in Ben Burgholzer’s “Border Waters,” Julia Spicher Kasdorf’s “They Call It a Strip Job,” and Byer’s “On Waterrock Knob,” exploitative land practices can result in irrecoverable damage to the environment and to those who depend on it for survival. In addition to destruction of the land to gain access to natural resources, Heather Ransom’s “Stockholm State: A History” exposes how the systems at work in the region can damage the region’s own citizens.

Clean drinking water and uncontaminated air are a necessity for everyone, including those with occupations that endanger the very land they inhabit. While it’s easy to associate destruction with exploitation, the other side of the argument brings about the issue of destruction of one’s way of life. In Ed Davis’s “Making Paradise,” the locals are terrified of losing their livelihood as loggers and paper manufacturing workers. Destruction can also be so simple that it becomes commonplace, as Michael McFee takes notice of in “Devil’s Rope.” It’s important to note that even destruction that appears to be nominal can wind up having a serious impact, and often the impact isn’t felt until intervention becomes a complicated and arduous matter.

When writing about environmental destruction, many authors choose to champion preservation. Preservation, in one sense, involves taking care of the environment rather than defending it from those who wish to exploit it for their own means. In this section, Brent Martin brings our attention to the history of conservationism and preservation in “Appalachian Wildness and the Death of the Sublime” by noting a historical issue that continues in many parts of Appalachia today: “Urban and industrial America called for conservation and preservation, while rural Americans, as well as corporate America, saw the vast expanse of publicly owned land as either a common space to be utilized or as a natural resource base to be exploited for profit.” Laura Henry-Stone discusses preservation in her essay, “Hemlocks, Adelgids, and People: Ecological Learning from an Appalachian Triad,” showing how even small-scale actions can make an impact.

Preservation in another sense can be seen as an action taken to avoid erasure of memories, customs, and histories. In this view of preservation, Gail Tyson’s “Man Talk” and “Frog and Tadpole,” and Julia Spicher Kasdorf’s “Home Farm,” portray the struggle of preserving one’s way of life. In these poems, we see how family and community members uphold traditions. Such writing of preservation has a lengthy history in the region. Much of Appalachian culture, including the indigenous cultures of the Ani’yunwi’ya (Cherokee), Shawanwa (Shawnee), Coyaha (Yuchi), Chikasha (Chickasaw), Lenape (Delaware), and Mvskoke Etvlwv (Muscogee/Creek), was, and still is, passed down through oral tradition. Unfortunately, as families and lineages are separated by forced removal, diaspora, migration, or simply death, these oral histories are not always passed on. Recording, by writing or other means, allows the continued existence of these histories and provides a way for future generations to learn about the cultural heritages of the Appalachian region. Emma Bell Miles’s The Spirit of the Mountains is one such example of writing to preserve the mountain culture, as are the narratives of Sarah Gudger, Dan Bogie, Harriet Mason, and many other former slaves, whose recorded experiences help add to our historical and cultural knowledge of the Appalachian region. In my essay “Uprooted,” I both preserve what I know about my family’s history and argue that the tradition of farming in Appalachia needs to be preserved and handed down as well. Preserving these stories of Appalachian individuals and communities allows us to understand and honor the full range of Appalachian experience.

While some community members may band together to preserve their livelihoods, other Appalachians may feel the need to protect themselves and their landscapes from these community members. Protection in Appalachia can look very different depending on which side you’re on. Since this collection focuses on nature, understandably the vast majority of works in this section center on protecting the natural world from the man-made forces that jeopardize it. In Katie Fallon’s “Forest Disturbance,” the vulnerable forest is put at risk by privately held mineral rights below its humus. In George Hovis’s “Your Mee-Maw vs. CXP Oil & Gas, LLC,” a grandmother takes a stand to protect her land from the effects of fracking. Rick Van Noy’s “Take in the Waters: On the Birthplace of Rivers, West Virginia” and Kathryn Stripling Byer’s “Waynesville Watershed” remind us of Wilma Dykeman’s warning in The French Broad: “Water is a living thing; it is life itself,” and if the water quality suffers, “all the network of creatures that live by water, including man himself” are in danger. Thomas Rain Crowe also echoes Dykeman’s sentiment that “if the fundamental ingredients of living [are] sounds and good, the furbelows [can] be done without.” In his essay, “In Praise of Wilderness: Getting What You Give Up,” Crowe suggests that in protecting the land, we are truly protecting ourselves. What these writers convey is a theme often found in Appalachian literature: that to survive on the land, one must protect it.

To close the section, Rosemary Royston takes us in a new direction: protecting oneself and one’s family by natural (and, save the death of a blackbird, largely nonviolent) folkloric methods. These poems and the suggested protection methods are based on Royston’s recent research from “Edain McCoy’s Mountain Magick: Folk Wisdom from the Heart of Appalachia, along with stories shared with [her] by those who’ve lived the majority of their lives in Appalachia.” Her poems both remind us of the region’s cultural heritage as well as how the region is ever evolving.

Evolving views on folkloric protection methods are just one way Appalachia has changed over the centuries. However, what comes to mind more immediately than myths when transformation and Appalachia are discussed is the industrial presence in the region. As industry progresses and changes the landscape as well as the way of life for many residents, uncertainty and anxiety creep in and are often expressed in the essays and poems in this section focusing on Appalachia’s evolution. The discussion of nature versus industry, or what some may tout as “progress,” particularly in Appalachia, has long been a source of fuel for writers. In an 1899 issue of McClure’s Magazine, Sarah Barnwell Elliott contributed a piece called “Progress,” centering on the feared changes of a widespread railroad industry. Concerns about change, whether largely unfounded or based on science and economics, continue today in the nature writing of Appalachia.

This section begins with Ann Pancake’s “Letter to West Virginia, November 2016,” exposing us to the contradictions and evolutions both the land and its people endure and the hopeful idea “that tearing down clears an emptiness for opportunity.” Writer doris diosa davenport’s “cycles and (scrambled) seasons” echoes this complex and often cyclic evolution of both nature and our own lives. In “High Water,” Mark Powell presents the transformation of numerous characters against a natural world that moves from foreground to background and back again in a sort of ethereal evolution all its own. Stephen Cushman’s “Love in the Age of Inattention” and Felicia Mitchell’s “Towhee” bring to light the effects of technology not only on human relationships but also on human relationships with nature. As Mitchell notes, “I am complicit here / . . . Without thinking, wasting electricity / I can disturb the universe.” While the effects of humans on nature cannot be negated, Libby Falk Jones, Larry D. Thacker, and Jesse Graves focus instead on the evolution of nature itself, particularly the signs of seasonal transformation, such as the “Bush budding white, crocus unfolding” in Jones’s “February Springtime in the Mountains” or the way in which “the first cold nights have curled / the edges of forest-floor ginger” in Graves’s “October Woods.” In many ways, these seasonal transitions shape our everyday lives.

These changes in season are more than just beautiful; they’re often reasons to celebrate. Just think of the way the natural world plays a role in many of our own celebrations. Many of us marvel at the first snow of the season or carve pumpkins for our front porches in late autumn. We spend time swimming in lakes and rivers at summertime get-togethers and hunt morels in the late spring. As prominent a role as nature plays, it’s no wonder artists and writers invoke its beauty in celebration. In this section focusing on such celebration, Jane Harrington’s “Settling” revels in the relief Cornelius is able to experience when met with opportunity in a difficult landscape. “How to Avoid the Widow Maker” by Jim Minick may not seem to be celebratory at first read—the speaker is felling trees, after all. However, triumphing over a widow maker certainly is celebratory, as knowledge and skill aren’t always enough to avoid a falling tree. These examples display the harmony that can arise when humans and nature are truly integrated.

The natural world can often remind us to celebrate those who mean the most to us as well. In Jeremy Michael Reed’s “In Tennessee I Found a Firefly,” the speaker’s time in the yard, alone except for fireflies, causes him to reflect on the love he shares with his partner: “the way love bends / over time, the way a hushed phrase / creates flash of lightning.” M. W. Smith’s speaker is also reminded to celebrate his loved one—a deceased grandfather—by the “eight hundred acres” this “unofficial town mayor” left behind. Whether it’s a hiking trail that we’ve trekked with a spouse or a fishing hole where we caught our first trout, nature is full of small reminders to honor our loved ones and experiences.

While the themes of honor and respect for nature are present in Susan Deer Cloud’s “Clingmans Dome Before Thanksgiving” and Lisa Ezzard’s “Wine Is the Color of Blood,” the respect is very much earned, as the speakers wrangle with the natural world. By juxtaposing a celebratory tone with surprisingly intimidating imagery, Deer Cloud’s “Spanish moss hanging like lynched ghosts / in the mists” and Ezzard’s “I spit and feel the sharp edge on the palate” may seem at odds initially. This combination, however, makes the celebration seem much more deserved, hard won. When Deer Cloud’s “lovers” are “lit to bedazzlement” among “frozen trees, broken weeds, limp grasses,” the reader knows that a journey through the natural world can be just as difficult as many of the other journeys we face, but just like the more mundane sojourns, the view at the end is often worth it. These pieces also serve as reminders that reasons to celebrate are perhaps not always easy to identify; it’s by excavating through the “gnarled vines” that we find true joy.

In whole, this collection represents a wide swath of Appalachian engagement with nature during a time of great environmental change. The natural world in Appalachia is incredibly significant for a variety of reasons—its obvious beauty, its ample biodiversity, and its struggle, the latter of which is indelibly tied to the Anthropocene. On a more national or global scale, the immense exploitation and degradation of the Appalachian landscape is both cause for concern and reason for hope: if people here can learn to live in balance and harmony with nature, then it’s possible anywhere. The writers in this collection seem to share the goal that, while it may not be easy, such a future is possible. While the spectrum and experiences can vary widely, as do the writers’ understandings and encounters with the natural world, they also implore us to explore the role nature plays in our own lives and communities and to deepen those connections in light of what the Anthropocene might mean for ourselves, our communities, and our world.

Cuprins

Chris Bolgiano

Taylor Brown

Ben Burgholzer

Kathryn Stripling Byer

Wayne Caldwell

Sarah Beth Childers

Jessica Cory

Chauna Craig

Thomas Rain Crowe

Stephen Cushman

doris diosa davenport

Ed Davis

Susan Deer Cloud

Lisa Ezzard

Katie Fallon

Carol Grametbauer

Jesse Graves

Jane Harrington

Lisa Hayes-Minney

Laura Henry-Stone

Scott Honeycutt

George Hovis

Gene Hyde

Libby Falk Jones

Madison Jones

Julia Spicher Kasdorf

Bill King

John Lane

Jeanne Larsen

Laura Long

Brent Martin

Michael McFee

Jim Minick

Felicia Mitchell

Ann Pancake

Ellen J. Perry

Mark Powell

Heather Ransom

Jeremy Michael Reed

John Robinson

Rosemary Royston

M. W. Smith

Larry D. Thacker

Gail Tyson

Rick Van Noy

G. C. Waldrep

Meredith Sue Willis

Amber M. Wright

David R. Young

Taylor Brown

Ben Burgholzer

Kathryn Stripling Byer

Wayne Caldwell

Sarah Beth Childers

Jessica Cory

Chauna Craig

Thomas Rain Crowe

Stephen Cushman

doris diosa davenport

Ed Davis

Susan Deer Cloud

Lisa Ezzard

Katie Fallon

Carol Grametbauer

Jesse Graves

Jane Harrington

Lisa Hayes-Minney

Laura Henry-Stone

Scott Honeycutt

George Hovis

Gene Hyde

Libby Falk Jones

Madison Jones

Julia Spicher Kasdorf

Bill King

John Lane

Jeanne Larsen

Laura Long

Brent Martin

Michael McFee

Jim Minick

Felicia Mitchell

Ann Pancake

Ellen J. Perry

Mark Powell

Heather Ransom

Jeremy Michael Reed

John Robinson

Rosemary Royston

M. W. Smith

Larry D. Thacker

Gail Tyson

Rick Van Noy

G. C. Waldrep

Meredith Sue Willis

Amber M. Wright

David R. Young

Textul de pe ultima copertă

Mountains Piled upon Mountains features nearly fifty writers from across Appalachia sharing their place-based fiction, literary nonfiction, and poetry. Moving beyond the tradition of transcendental nature writing, much of the work collected here engages current issues facing the region and the planet (such as hydraulic fracturing, water contamination, mountaintop removal, and deforestation), and provides readers with insights on the human-nature relationship in an era of rapid environmental change.

This book includes a mix of new and recent creative work by established and emerging authors. The contributors write about experiences from northern Georgia to upstate New York, invite parallels between a watershed in West Virginia and one in North Carolina, and often emphasize connections between Appalachia and more distant locations. In the pages of Mountains Piled upon Mountains are celebration, mourning, confusion, loneliness, admiration, and other emotions and experiences rooted in place but transcending Appalachia’s boundaries.

This book includes a mix of new and recent creative work by established and emerging authors. The contributors write about experiences from northern Georgia to upstate New York, invite parallels between a watershed in West Virginia and one in North Carolina, and often emphasize connections between Appalachia and more distant locations. In the pages of Mountains Piled upon Mountains are celebration, mourning, confusion, loneliness, admiration, and other emotions and experiences rooted in place but transcending Appalachia’s boundaries.