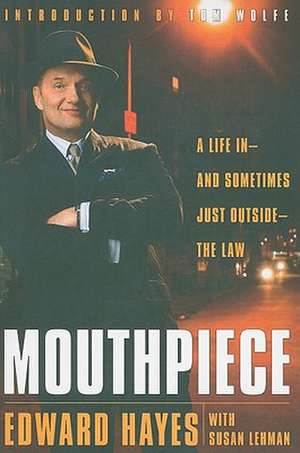

Mouthpiece: A Life in -- And Sometimes Just Outside -- The Law

Autor Edward Hayes Tom Wolfe Susan Lehmanen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 dec 2009

“In the pages before us, the Counselor tells a saga’s worth of tales of the city. As the saying goes, he’s got a million of them.” —Tom Wolfe, from his Introduction

Edward Hayes is that unusual combination: the likable lawyer, one who could have stepped off the stages of Guys and Dolls or Chicago. Mouthpiece is his story—an irreverent, entertaining, and revealing look at the practice of law in modern times and a social and political anatomy of New York City. It recounts Hayes’s childhood in the tough Irish sections of Queens and his eventual escape to the University of Virginia and then to Columbia Law School. Not at all white-shoe-firm material, Hayes headed to the hair-raising, crime-ridden South Bronx of the midseventies—first as a homicide prosecutor and then as a defense attorney seeking to free the same sort of people he formerly had put in jail.

Tom Wolfe immortalized this setting in The Bonfire of the Vanities. Ed Hayes was his guide, and he served as the model for the scrappy defense lawyer Tommy Killian. Eventually, Hayes moved his practice to Manhattan, using his neighborhood white boy instincts and connections and the rough-and-tumble techniques learned in the Bronx on behalf of the rich and powerful and famous. From a high-stakes legal shootout over the Andy Warhol estate to working to secure financial justice for the families of the World Trade Center victims, Hayes has been behind the scenes of how New York City really operates.

For the tens of millions fascinated by New York’s unique blend of glitter and grime, of idealism and corruption, of avarice and ambition, Mouthpiece provides the ultimate close-up of high-stakes Gotham gamesmanship.

Preț: 120.78 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 181

Preț estimativ în valută:

23.11€ • 24.19$ • 19.24£

23.11€ • 24.19$ • 19.24£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 10-24 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780767916547

ISBN-10: 0767916549

Pagini: 288

Ilustrații: 1 8-PAGE B&W INSERT

Dimensiuni: 152 x 226 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.43 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0767916549

Pagini: 288

Ilustrații: 1 8-PAGE B&W INSERT

Dimensiuni: 152 x 226 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.43 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

Recenzii

Praise for Mouthpiece

“Ed Hayes has an almost unique ability to treat ‘kings and paupers, one and both the same’; indeed, he has prosecuted or defended both at one time or another in his career. Anyone who has seen Eddie in action recognizes that he is as articulate as he is colorful. His book, Mouthpiece, proves ‘beyond a reasonable doubt’ that he is also one of the most effective lawyers practicing today.”

—Henry S. Schlieff, Chairman & CEO, Court TV

“Eddie Hayes has more excitement in real life than any lawyer in the movies.”

—Robert DeNiro

“Eddie Hayes walks, talks, and acts like a character created by Damon Runyon, but he’s even better because he’s the real thing.”

—William Bratton, former Police Commissioner of Boston and New York, current Chief of Police, Los Angeles

“Whether it’s his blistering performances in court, or his Savile Row chalkstripe suits, Ed Hayes has always been a law unto himself. Half of New York society is in his memoirs—the other half is trying to stay well out of his sights.”

—Anna Wintour, Editor-in-Chief, Vogue

“In the battle between good and evil, Ed Hayes is on both sides. After reading Mouthpiece I don’t know whether to congratulate him or arrest him.”

—John Timoney, City of Miami Police Chief, former First Deputy Commissioner, New York City Police Department

“Thanks to Eddie Hayes, I never got what I deserved.”

—Little Georgie (not his real name)

“Ed Hayes has an almost unique ability to treat ‘kings and paupers, one and both the same’; indeed, he has prosecuted or defended both at one time or another in his career. Anyone who has seen Eddie in action recognizes that he is as articulate as he is colorful. His book, Mouthpiece, proves ‘beyond a reasonable doubt’ that he is also one of the most effective lawyers practicing today.”

—Henry S. Schlieff, Chairman & CEO, Court TV

“Eddie Hayes has more excitement in real life than any lawyer in the movies.”

—Robert DeNiro

“Eddie Hayes walks, talks, and acts like a character created by Damon Runyon, but he’s even better because he’s the real thing.”

—William Bratton, former Police Commissioner of Boston and New York, current Chief of Police, Los Angeles

“Whether it’s his blistering performances in court, or his Savile Row chalkstripe suits, Ed Hayes has always been a law unto himself. Half of New York society is in his memoirs—the other half is trying to stay well out of his sights.”

—Anna Wintour, Editor-in-Chief, Vogue

“In the battle between good and evil, Ed Hayes is on both sides. After reading Mouthpiece I don’t know whether to congratulate him or arrest him.”

—John Timoney, City of Miami Police Chief, former First Deputy Commissioner, New York City Police Department

“Thanks to Eddie Hayes, I never got what I deserved.”

—Little Georgie (not his real name)

Notă biografică

Edward Hayes now practices law in Manhattan for a wide variety of influential and/or notorious clients. He co-anchors Both Sides for Court TV and broadcasts once a week on WABC Talk Radio. He is an inductee into the International Best Dressed Hall of Fame.

Susan Lehman, a former criminal defense lawyer, was senior editor at Riverhead Books, Talk magazine, and Salon.com. She has written about the law, crime and other topics for the New York Observer, the Washington Post, and other publications.

Tom Wolfe is the famed author of The Bonfire of the Vanities, The Right Stuff, and, most recently, I Am Charlotte Simmons.

Susan Lehman, a former criminal defense lawyer, was senior editor at Riverhead Books, Talk magazine, and Salon.com. She has written about the law, crime and other topics for the New York Observer, the Washington Post, and other publications.

Tom Wolfe is the famed author of The Bonfire of the Vanities, The Right Stuff, and, most recently, I Am Charlotte Simmons.

Extras

CHAPTER 1

I learned as a child not to expect to be loved for myself.

My father was a very good teacher.

I don't have a single good memory of him, not one, but he taught me a lot of useful lessons. A merchant marine during World War II, my father had gone on missions to Murmansk and Malta on a tanker and he told me how, during those voyages, American destroyers rammed German subs and the subs torpedoed the tankers and, in the end, the water was full of sailors who had been blown to bits or were on fire. They fought to the death. I remember thinking, That's the way life is: somebody goes home and somebody does not, you try to avoid the latter, but that's how life is.

I learned this early on, and also that people are weak and can't control themselves and you have to protect yourself from that.

All in all, pretty useful things to learn, especially if you live in New York. New York, this City of Ambition is brutal, unrelenting, dense, neurotic, always alive, and, if you're willing to take a chance and pay the price, you can get what you want here, or at least close enough. The whole city is full of guys who can take beatings, guys who got beaten somewhere else but crossed the ocean to get here and take another one and who will get up tomorrow to do the same thing.

I was born Edward Walter Hayes on November 3, 1947, at Physicians Hospital in Jackson Heights, Queens. It was a difficult breech birth and the doctor, who was Jewish, had to reach in and ease me out, which saved my life and was my first good experience with Jews. But my breathing was strange and Dr. Goldberg didn't think I would live long. So Father Cunningham, the priest who had married my parents a year before, was dispatched to baptize me right away.

My mother does not know where my father was at the time, but he wasn't there, for either the birth or the baptism. My mom says he was probably out in the waiting room, fainting or drinking.

I made little squeaking sounds,--"Ehhhh"--and couldn't cry for four months after they got me home from the hospital. My mom worried about this and about some trouble she thought I seemed to have eating, but she says my father was not too concerned. About this, my father's response seems to have been just right: after a while the squeaking stopped; I have never had trouble eating or crying since; and the years we lived in the four-story red brick house on Eighty-sixth Street were the best of my childhood.

The house cost four thousand dollars. My aunt Nonie bought it courtesy of Bill Fitzgibbon, who worked at Grant's department store and had nice cufflinks and silk shirts and may have been the first Irish affirmative action hire in the history of New York and who for years courted Aunt Nonie until finally she agreed to marry him. Fitzgibbon promptly became a hopeless drunk and died an awful death a year later, but he left Aunt Nonie with the four thousand dollars she needed to buy the brick town house on Eighty-sixth Street.

In Jackson Heights, there are tales (true, partly true, or not at all true) that are told and retold so many times they eventually take shape as actual, incontrovertible fact. They're called Irish facts. Aunt Nonie was orphaned ten years earlier when her father, Francis McCade, a tombstone cutter, died of consumption; Nonie was dispatched to a wealthy family, the head of which was a fashionable dressmaker who taught Aunt Nonie her craft. Is it an Irish fact that Nonie first caught Bill Fitzgibbon's eye as she bent her pretty head over a sewing machine? No idea, but I know that Fitzgibbon supplied Aunt Nonie with her one chance at love and that she took it; it didn't turn out well, but the story introduced an idea central to the rest of my life: everyone, even an orphaned seamstress, gets at least one shot at something and you're a fool not to take your chance when you get it; it might not work out, but there could be a house full of happy memories in it for someone.

Decades of white-boy history ran down Eighty-sixth Street and all the other streets in Jackson Heights, a neighborhood of garden apartments and family homes inhabited then--as now--mostly by immigrants hungry for a taste of some chicken-in-every-pot, car-in-every-garage-type American prosperity.

Brits Out. Before any of us Irish kids had any idea what it meant or even who the Brits were, this was pretty much the first thing any of us who ran around the streets and the alleyways behind our garden apartments had to say about anything. We all went to the same parish church and held the same beliefs. Chief among these was the idea that the worst thing you can do is rat out a friend, and that if you did you would (and should) be killed, and that life is cruel and harsh and the best you can do is die for your faith, and that the point of life is to know God and be with Him forever and the purpose of this life is for the next. Also God will forgive you for everything, but I don't have to. (He will forgive you. I will blow up your car.) We were also told from early on that Jews killed Christ. But that was very long ago in some messed-up place with camels, so who cared? And besides, we didn't know any Jews.

The Italian kids had good food, the Germans had decent pastry, and the Irish had neither, but we kids had the same heroes: Frank Gifford, firemen, cops, baseball players. Right from the womb, everyone knew about the charming and brilliant Irish military leader Michael Collins, who helped start an uprising in 1916, when he joined a small force of Irish guys enraged at the British Empire encamped in the Sackville Street General Post Office in Dublin, in particular. Though British troops instantly surrounded the post office and fired mercilessly, the ragtag team of Irishmen held their ground and fought it out for days and days, choosing to fight long past what common sense or honor required rather than retreat or give even an inch. When, exhausted but triumphant, they finally surrendered, the British soldiers fucking hung every single one of the leaders (though not Collins), including Joseph Plunkett, who led the whole thing, and his little brother, who was just along for the ride.

The neighborhood white boys all had the same general expectation as to how things might play out for them during the next seventy or eighty years: we would love God, get jobs like our dads, marry nice Catholic girls. And live in Jackson Heights--or maybe even, if we were lucky, Forest Hills or Kew Gardens--and have houses full of kids who would go to St. Joan of Arc school as we did and would fight in the alleyways and streets and knock each other's blocks off, mostly for fun, as we also did.

"Stupid. Asshole. Shithead.

"

The Italian kid, an eleven- or twelve-year-old with slicked-back black hair who lives across the street, throws a rock that lands with a crash near my feet. The crew of kids I play with, eight-, nine-, and ten-year-olds, run away, laughing.

"Who's a stupid asshole?" I say.

I'm skinny but I'm not running away.

(Even at nine, I'm not big on retreat.)

Beat me. So what?

Boom, smack.

The Italian kid lands a punch on my left shoulder. Another on my upper arm.

My little brother, Steven, and a crowd of kids edge closer to watch the dark-haired Italian slam his hand into my skinny chest again and again. Probably they wonder why on earth a scrawny little kid would frantically thrash around on the ground with someone twice his size rather than shrug, say something like "Forget it, will ya?" and walk off. Instead, and with all the fury in my little nine-year-old heart, I pound my fists against the kid from across the street. The crazed anger I taste in my mouth when my father beats me at home sparks up my throat when, a moment later, I roll on the asphalt drive toward a closed garage door, into the hard white wood of which he kicks my flailing legs, again and again.

The group watching has grown and now includes at least eight or nine people bigger than the Italian kid and certainly big enough to intervene and stop the whole thing. If they want to, which they don't.

Isn't anyone going to help? The thought crosses my mind as my head smashes against the garage door. I look up at Mick and Paddy and Joe, who live on the block, and Francis, Thomas, and Billy, who I know from school. Jackson Heights is a neighborhood in which you see everyone you know at least three times a day, including all the kids I fight with on the playground. No, I think, as the Italian kid kicks me, blinding white fury burning behind my eyes. No. No one is going to help.

Wonder Bread. I need Wonder Bread. That's what I thought as I picked myself up off the ground when the whole thing was over and the kids, except for my brother, who seemed always to be there then (and also throughout the rest of my life), went off to knock someone else's block off or to have dinner--meatballs or something equally terrific, at least for the Italian kids. (Who remembers, or wants to remember, what the German or Irish kids ate?)

My maternal grandfather, Walter Sowden, drove a Wonder Bread truck and was one of the loveliest men I knew. The only one of my four grandparents who wasn't Irish or Catholic, Walter Sowden grew up in poverty in Greenpoint, Brooklyn; my mom says he married into an Irish Catholic family because he wanted a place in a more vibrant culture. Whether he found it or not, I don't know, but I do know that my grandmother, Mary Fitzgibbon Sowden, a devout Catholic, went to church every day of her life and prayed that her Lutheran husband would convert. He never did, but they had what looked like a truly bonded, wonderful marriage, and there was always a cupboard full of Wonder Bread in their two-bedroom apartment, which was walking distance from the house and also the alleyway where the Italian kid shoved my skull into the garage door.

"Want some bread and jelly?" That's all Grandpa Walter ever said to me. He never once asked how I'd gotten bruised or why my knees were skinned.

Fight. Eat Wonder Bread. Go out, fight again. That's it--one of my favorite childhood routines. During those years in Jackson Heights, I think I ate more Wonder Bread than anyone in the world.

"Bye, Grandpa," I'd say after I finished my bread and stood up, ready to go back into the street. "Be good, Eddie," Grandpa Sowden would say as he walked me to the door. And then, Steven right behind me, I'd head outside, looking for another fight or, better yet, the same fight, with the same dark-haired kid who took me down an hour ago. That's how it always was: if I won a fight, which I rarely did, it was over, we could be friends. But if I lost, as I usually did and as I had to the Italian kid, I'd keep fighting, today and tomorrow and the days after, long past the point where I or anyone else could possibly remember what the beef (assuming there was one) had been in the first place. I'd keep at it forever. There was always more bread.

"Corpus Domini nostri Jesu Christi custodiat animam tuam in vitam aeternam." The body of our Lord Jesus Christ, may it preserve your soul unto life everlasting.

I kneel before the altar in St. Joan of Arc church. My mom is there in a fancy dress and my brother, Steven, and my aunt Nonie, who is always with my mother at meals or, when the weather is good, outside on the steps talking with her mom, watching to make sure Steven and I don't get in trouble in the street and certainly in church. The Sowdens and the Hayeses all sit together on a wood pew in the third row--I see them as I face the priest as he puts the Communion wafer in my mouth.

It feels good to be here, in my Sunday clothes, my blue blazer and the white shirt my mom ironed the night before even though it is perma-press and doesn't need pressing. Catholics all over the world take Communion, eat the same wafers, and say the same prayers about taking His body and blood into their own; I know this from catechism class. I don't know a single person besides my grandfather who isn't Catholic, and perhaps it doesn't even occur to me that there is anyone in the world who isn't, but it still makes me feel safe and happy to take Communion and feel connected.

Engraved in the very stones of St. Joan of Arc church, where I took my first Communion and felt connected with Catholics around the world--and with Mick and Paddy and Joe and the other kids I fought in the streets after (and also before) church--are the words Love Thy Neighbor as Thyself.

Love Thy Neighbor as Thyself. Okay. I did, I would. I'd love them all--Mick, Paddy, and Joe--even when they beat my balls off in the alley, which they sometimes did immediately following church on Sunday.

Everything I wanted to do was wrong. This I learned at church and also at St. Joan of Arc school, which was across the play lot from church. But as long as I repent, God would forgive me for whatever I did, no matter how bad. I learned a lot about forgiveness at school and about repentance and redemption, which were useful concepts to take with me when I went home to my family each night.

I loved the nuns who taught me about forgiveness and also taught me religious history. The sisters were good-hearted people who, as my mother explained, had made the ultimate sacrifice for God, and even (or especially) to a child, they seemed genuinely dedicated. I felt they really cared about me. The fact that they also smacked me around? I didn't care. I adored nuns. I still do.

The nuns wore habits that made them scary and they didn't like to be questioned much. Sister Cherubim, the lovely woman, taught us about the Inquisition, a subject that struck a real chord with me. (When people or groups of people got hurt, I could relate.) "Why did the Catholics torture all those people? What did the Jews do?" I am nine and I want to know. I keep pushing. "What did they do?" Like most of the other nuns at St. Joan of Arc, Sister Cherubim is particularly unreceptive to political questions. "They got tortured, killed. What did all these people do to provoke this?" I asked again and again.

From the Hardcover edition.

I learned as a child not to expect to be loved for myself.

My father was a very good teacher.

I don't have a single good memory of him, not one, but he taught me a lot of useful lessons. A merchant marine during World War II, my father had gone on missions to Murmansk and Malta on a tanker and he told me how, during those voyages, American destroyers rammed German subs and the subs torpedoed the tankers and, in the end, the water was full of sailors who had been blown to bits or were on fire. They fought to the death. I remember thinking, That's the way life is: somebody goes home and somebody does not, you try to avoid the latter, but that's how life is.

I learned this early on, and also that people are weak and can't control themselves and you have to protect yourself from that.

All in all, pretty useful things to learn, especially if you live in New York. New York, this City of Ambition is brutal, unrelenting, dense, neurotic, always alive, and, if you're willing to take a chance and pay the price, you can get what you want here, or at least close enough. The whole city is full of guys who can take beatings, guys who got beaten somewhere else but crossed the ocean to get here and take another one and who will get up tomorrow to do the same thing.

I was born Edward Walter Hayes on November 3, 1947, at Physicians Hospital in Jackson Heights, Queens. It was a difficult breech birth and the doctor, who was Jewish, had to reach in and ease me out, which saved my life and was my first good experience with Jews. But my breathing was strange and Dr. Goldberg didn't think I would live long. So Father Cunningham, the priest who had married my parents a year before, was dispatched to baptize me right away.

My mother does not know where my father was at the time, but he wasn't there, for either the birth or the baptism. My mom says he was probably out in the waiting room, fainting or drinking.

I made little squeaking sounds,--"Ehhhh"--and couldn't cry for four months after they got me home from the hospital. My mom worried about this and about some trouble she thought I seemed to have eating, but she says my father was not too concerned. About this, my father's response seems to have been just right: after a while the squeaking stopped; I have never had trouble eating or crying since; and the years we lived in the four-story red brick house on Eighty-sixth Street were the best of my childhood.

The house cost four thousand dollars. My aunt Nonie bought it courtesy of Bill Fitzgibbon, who worked at Grant's department store and had nice cufflinks and silk shirts and may have been the first Irish affirmative action hire in the history of New York and who for years courted Aunt Nonie until finally she agreed to marry him. Fitzgibbon promptly became a hopeless drunk and died an awful death a year later, but he left Aunt Nonie with the four thousand dollars she needed to buy the brick town house on Eighty-sixth Street.

In Jackson Heights, there are tales (true, partly true, or not at all true) that are told and retold so many times they eventually take shape as actual, incontrovertible fact. They're called Irish facts. Aunt Nonie was orphaned ten years earlier when her father, Francis McCade, a tombstone cutter, died of consumption; Nonie was dispatched to a wealthy family, the head of which was a fashionable dressmaker who taught Aunt Nonie her craft. Is it an Irish fact that Nonie first caught Bill Fitzgibbon's eye as she bent her pretty head over a sewing machine? No idea, but I know that Fitzgibbon supplied Aunt Nonie with her one chance at love and that she took it; it didn't turn out well, but the story introduced an idea central to the rest of my life: everyone, even an orphaned seamstress, gets at least one shot at something and you're a fool not to take your chance when you get it; it might not work out, but there could be a house full of happy memories in it for someone.

Decades of white-boy history ran down Eighty-sixth Street and all the other streets in Jackson Heights, a neighborhood of garden apartments and family homes inhabited then--as now--mostly by immigrants hungry for a taste of some chicken-in-every-pot, car-in-every-garage-type American prosperity.

Brits Out. Before any of us Irish kids had any idea what it meant or even who the Brits were, this was pretty much the first thing any of us who ran around the streets and the alleyways behind our garden apartments had to say about anything. We all went to the same parish church and held the same beliefs. Chief among these was the idea that the worst thing you can do is rat out a friend, and that if you did you would (and should) be killed, and that life is cruel and harsh and the best you can do is die for your faith, and that the point of life is to know God and be with Him forever and the purpose of this life is for the next. Also God will forgive you for everything, but I don't have to. (He will forgive you. I will blow up your car.) We were also told from early on that Jews killed Christ. But that was very long ago in some messed-up place with camels, so who cared? And besides, we didn't know any Jews.

The Italian kids had good food, the Germans had decent pastry, and the Irish had neither, but we kids had the same heroes: Frank Gifford, firemen, cops, baseball players. Right from the womb, everyone knew about the charming and brilliant Irish military leader Michael Collins, who helped start an uprising in 1916, when he joined a small force of Irish guys enraged at the British Empire encamped in the Sackville Street General Post Office in Dublin, in particular. Though British troops instantly surrounded the post office and fired mercilessly, the ragtag team of Irishmen held their ground and fought it out for days and days, choosing to fight long past what common sense or honor required rather than retreat or give even an inch. When, exhausted but triumphant, they finally surrendered, the British soldiers fucking hung every single one of the leaders (though not Collins), including Joseph Plunkett, who led the whole thing, and his little brother, who was just along for the ride.

The neighborhood white boys all had the same general expectation as to how things might play out for them during the next seventy or eighty years: we would love God, get jobs like our dads, marry nice Catholic girls. And live in Jackson Heights--or maybe even, if we were lucky, Forest Hills or Kew Gardens--and have houses full of kids who would go to St. Joan of Arc school as we did and would fight in the alleyways and streets and knock each other's blocks off, mostly for fun, as we also did.

"Stupid. Asshole. Shithead.

"

The Italian kid, an eleven- or twelve-year-old with slicked-back black hair who lives across the street, throws a rock that lands with a crash near my feet. The crew of kids I play with, eight-, nine-, and ten-year-olds, run away, laughing.

"Who's a stupid asshole?" I say.

I'm skinny but I'm not running away.

(Even at nine, I'm not big on retreat.)

Beat me. So what?

Boom, smack.

The Italian kid lands a punch on my left shoulder. Another on my upper arm.

My little brother, Steven, and a crowd of kids edge closer to watch the dark-haired Italian slam his hand into my skinny chest again and again. Probably they wonder why on earth a scrawny little kid would frantically thrash around on the ground with someone twice his size rather than shrug, say something like "Forget it, will ya?" and walk off. Instead, and with all the fury in my little nine-year-old heart, I pound my fists against the kid from across the street. The crazed anger I taste in my mouth when my father beats me at home sparks up my throat when, a moment later, I roll on the asphalt drive toward a closed garage door, into the hard white wood of which he kicks my flailing legs, again and again.

The group watching has grown and now includes at least eight or nine people bigger than the Italian kid and certainly big enough to intervene and stop the whole thing. If they want to, which they don't.

Isn't anyone going to help? The thought crosses my mind as my head smashes against the garage door. I look up at Mick and Paddy and Joe, who live on the block, and Francis, Thomas, and Billy, who I know from school. Jackson Heights is a neighborhood in which you see everyone you know at least three times a day, including all the kids I fight with on the playground. No, I think, as the Italian kid kicks me, blinding white fury burning behind my eyes. No. No one is going to help.

Wonder Bread. I need Wonder Bread. That's what I thought as I picked myself up off the ground when the whole thing was over and the kids, except for my brother, who seemed always to be there then (and also throughout the rest of my life), went off to knock someone else's block off or to have dinner--meatballs or something equally terrific, at least for the Italian kids. (Who remembers, or wants to remember, what the German or Irish kids ate?)

My maternal grandfather, Walter Sowden, drove a Wonder Bread truck and was one of the loveliest men I knew. The only one of my four grandparents who wasn't Irish or Catholic, Walter Sowden grew up in poverty in Greenpoint, Brooklyn; my mom says he married into an Irish Catholic family because he wanted a place in a more vibrant culture. Whether he found it or not, I don't know, but I do know that my grandmother, Mary Fitzgibbon Sowden, a devout Catholic, went to church every day of her life and prayed that her Lutheran husband would convert. He never did, but they had what looked like a truly bonded, wonderful marriage, and there was always a cupboard full of Wonder Bread in their two-bedroom apartment, which was walking distance from the house and also the alleyway where the Italian kid shoved my skull into the garage door.

"Want some bread and jelly?" That's all Grandpa Walter ever said to me. He never once asked how I'd gotten bruised or why my knees were skinned.

Fight. Eat Wonder Bread. Go out, fight again. That's it--one of my favorite childhood routines. During those years in Jackson Heights, I think I ate more Wonder Bread than anyone in the world.

"Bye, Grandpa," I'd say after I finished my bread and stood up, ready to go back into the street. "Be good, Eddie," Grandpa Sowden would say as he walked me to the door. And then, Steven right behind me, I'd head outside, looking for another fight or, better yet, the same fight, with the same dark-haired kid who took me down an hour ago. That's how it always was: if I won a fight, which I rarely did, it was over, we could be friends. But if I lost, as I usually did and as I had to the Italian kid, I'd keep fighting, today and tomorrow and the days after, long past the point where I or anyone else could possibly remember what the beef (assuming there was one) had been in the first place. I'd keep at it forever. There was always more bread.

"Corpus Domini nostri Jesu Christi custodiat animam tuam in vitam aeternam." The body of our Lord Jesus Christ, may it preserve your soul unto life everlasting.

I kneel before the altar in St. Joan of Arc church. My mom is there in a fancy dress and my brother, Steven, and my aunt Nonie, who is always with my mother at meals or, when the weather is good, outside on the steps talking with her mom, watching to make sure Steven and I don't get in trouble in the street and certainly in church. The Sowdens and the Hayeses all sit together on a wood pew in the third row--I see them as I face the priest as he puts the Communion wafer in my mouth.

It feels good to be here, in my Sunday clothes, my blue blazer and the white shirt my mom ironed the night before even though it is perma-press and doesn't need pressing. Catholics all over the world take Communion, eat the same wafers, and say the same prayers about taking His body and blood into their own; I know this from catechism class. I don't know a single person besides my grandfather who isn't Catholic, and perhaps it doesn't even occur to me that there is anyone in the world who isn't, but it still makes me feel safe and happy to take Communion and feel connected.

Engraved in the very stones of St. Joan of Arc church, where I took my first Communion and felt connected with Catholics around the world--and with Mick and Paddy and Joe and the other kids I fought in the streets after (and also before) church--are the words Love Thy Neighbor as Thyself.

Love Thy Neighbor as Thyself. Okay. I did, I would. I'd love them all--Mick, Paddy, and Joe--even when they beat my balls off in the alley, which they sometimes did immediately following church on Sunday.

Everything I wanted to do was wrong. This I learned at church and also at St. Joan of Arc school, which was across the play lot from church. But as long as I repent, God would forgive me for whatever I did, no matter how bad. I learned a lot about forgiveness at school and about repentance and redemption, which were useful concepts to take with me when I went home to my family each night.

I loved the nuns who taught me about forgiveness and also taught me religious history. The sisters were good-hearted people who, as my mother explained, had made the ultimate sacrifice for God, and even (or especially) to a child, they seemed genuinely dedicated. I felt they really cared about me. The fact that they also smacked me around? I didn't care. I adored nuns. I still do.

The nuns wore habits that made them scary and they didn't like to be questioned much. Sister Cherubim, the lovely woman, taught us about the Inquisition, a subject that struck a real chord with me. (When people or groups of people got hurt, I could relate.) "Why did the Catholics torture all those people? What did the Jews do?" I am nine and I want to know. I keep pushing. "What did they do?" Like most of the other nuns at St. Joan of Arc, Sister Cherubim is particularly unreceptive to political questions. "They got tortured, killed. What did all these people do to provoke this?" I asked again and again.

From the Hardcover edition.