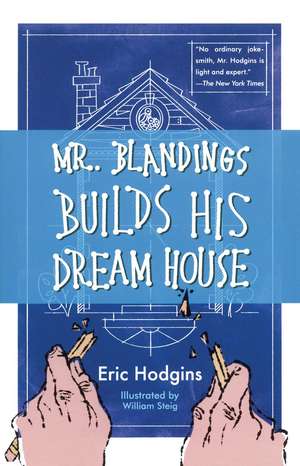

Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House

Autor Eric Hodgins Ilustrat de William Steigen Limba Engleză Paperback – 11 feb 2005

Mr. Blandings, a successful New York advertising executive, and his wife want to escape the confines of their tiny midtown apartment. They design the perfect home in the idyllic country, but soon they are beset by construction troubles, temperamental workmen, skyrocketing bills, threatening lawyers, and difficult neighbors. Mr. Blandings' dream house soon threatens to be the nightmare that undoes him.

This internationally bestselling book by Eric Hodgins is illustrated by William Steig and was made into a film starring Cary Grant and Myrna Loy -- and a later film starring Tom Hanks called The Money Pit.

Preț: 95.36 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 143

Preț estimativ în valută:

18.25€ • 19.83$ • 15.34£

18.25€ • 19.83$ • 15.34£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 31 martie-14 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780743262323

ISBN-10: 0743262328

Pagini: 240

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: Simon&Schuster

Colecția Simon & Schuster

ISBN-10: 0743262328

Pagini: 240

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: Simon&Schuster

Colecția Simon & Schuster

Notă biografică

William Steig (1907–2003) was a cartoonist, illustrator, and author of award-winning books for children. Most notably Sylvester and the Magic Pebble, for which he received the Caldecott Medal; The Amazing Bone, a Caldecott Honor book; Amos & Boris, a National Book Award Finalist; and Abel’s Island and Doctor De Soto, both Newbery Honor books. Steig is also the creator of Shrek! which inspired the Dreamworks films. Steig also received the Christopher Award, the Irma Simonton Black Award, the William Allen White Children’s Book Award, the America Book Award, and Society of Illustrators Lifetime Achievement Award. He was also the US nominee for both of the biennial, international Hans Christian Andersen Awards as an illustrator in 1982, and then as an author in 1988. He is survived by his wife, Jeanne Steig, and four children.

Extras

Chapter One: The Real-Estate Man

The sweet old farmhouse burrowed into the upward slope of the land so deeply that you could enter either its bottom or middle floor at ground level. Its window trim was delicate and the lights in its sash were a bubbly amethyst. Its rooftree seemed to sway a little against the sky, and the massive chimney that rose out of it tilted a fraction to the south. Where the white paint was flecking off on the siding, there showed beneath it the faint blush of what must once have been a rich, dense red.

In front of it, rising and spreading along the whole length of the house, was the largest lilac tree that Mr. and Mrs. Blandings had ever seen. Its gnarled, rusty trunks rose intertwined to branch and taper into splays of this year's light young wood; they, in turn, burst into clouds of blossoms that made the whole vast thing a haze of blues and purples, billowed and wafting. When the house was new, the lilac must have been a shrub in the dooryard -- and house and shrub had gone on together, side by side since then. That was a hundred and seventy years ago, last April.

"If the lilac can live and be so old, so can the house," Mrs. Blandings said to herself. "It needs someone to love it, that's all." She flashed a glance at her husband, who flashed one back at her.

Using a penknife as a key, the real-estate man unlocked a lower door. As it swung back, the top hinge gave way and splashed in a brown powder on the floor. The door lurched against Mr. Blandings, and gave him a sharp crack on the forehead, but the damage was repaired in an instant, and Mr. Blandings, a handkerchief at his temple and his wife by his side, stood looking out through the amethyst window lights at an arc of beauty that made them both cry out. The land rushed downward to the river a mile away; then it rose again, layer after layer, plane after plane of hills and higher hills lighter beyond them. The air was luminous, and there were twenty shades of browns and greens in the plowed and wooded and folded earth.

"On a clear day you can see the Catskills," said the real-estate man.

Mr. and Mrs. Blandings were not such fools as to exclaim at this revelation. Mrs. Blandings flicked a glove in which a cobweb and free-running spider had become entangled; Mr. Blandings, his lips pursed and his eyes half closed, was a picture of controlled reserve; strong, realistic, poised. By the way the two of them said "Uh-huh?" with a rising inflection in perfect unison, the real-estate man knew that his sale was made. The offer would not come today, of course; it might, indeed, not come for a fortnight. But it would come; it would come with all the certainty of the equinox. He computed five per cent of $10,275 in his head and turned to the chimney footing.

"You'd have to do a little pointing up here," he said, indicating a compact but disorderly pile of stone in which a blackened hollow suggested a fireplace that had been in good working order at the time of the Treaty of Ghent. Mrs. Blandings, looking at the rubble, saw instead the kitchen of the Wayside Inn: a distaff plump with flax lying idly on the polished hearth; a tempered scale of copper pans and skillets pegged to hang heads downward near the oven wall; a bootjack in the corner and a shoat glistening on the spit.

What Mr. Blandings saw broke through into speech. "With a flagstone floor in here it'd be a nice place for a beer party on a Saturday night. You could put the keg right over in that corner."

He laughed a mild laugh which meant to say that if his thought was frivolous so, indeed, was the whole occasion that had called it forth. The notion that he might buy this old farmhouse, or any other, anywhere, ever, was light, gossamer nonsense; a whimsy; a caprice; it was his pleasure to give it a momentary fiction of solidity.

The real-estate man refused to take Mr. Blandings' suggestion so lightly. "You could at that," he said, awe and rumination mixed in his voice, as though he had just heard a brilliant restatement of nuclear theory. He quickly did five per cent of $11,550 in his head; aloud he said: "You haven't seen what's on the other side, either."

Mr. and Mrs. Blandings stepped across a mound of rubbish on the cold earthen floor and saw an even more impressive example of masonry in disarray. The second fireplace, loosely connected to the same flue as the first, stood at an angle with it that made a rough, bold V. Its stones were even more massive; hearth and manteltree were both huge monoliths. No frame of reference in all Euclid could be taken to which any major piece would be plumb, level, or square, but it was the work of a moment for Mr. Blandings to set everything to rights and swing a polished black kettle on its crane over the glowing ashes of an oak that he himself had sawn and quartered. In a moment he would have a mug of hot rum to banish the cold from his ten-mile plunge through the snowdrifts to rescue the heifer his hired man had abandoned for lost....

"They must have done their slaughtering down here years ago," said the real-estate man. "You don't see an old kettle like that every day in the week, not even in this part of the country."

The Blandings followed his forefinger and saw, on a circular pedestal of stone to the right of the hearth, a huge hemisphere of somber metal. Mr. Blandings thumped it lightly with his fist and it gave forth a hushed, whispering boom. "I think they filled that full of boiling water and scalded the hide off the pig before they dismembered him. Anyway, they must have hung their hams and bacon flitches on those hooks up there."

Mrs. Blandings, the membra disjecta of whose broiling chickens came to her kitchen packed into neat rectangles from the frozen-food store near her city apartment, contemplated the slaughtering of a 300-pound hog with ease, and observed the slender beauty of the hooks sunk deep in the old beams; hooks that had been shaped and pointed on some anvil lost in the tall grasses of a century ago.

"Mind your head as we make the turn," said the real-estate man, leading his prospects into a gloom in which a stairway could be faintly discerned. "I want you to see the living room just the way it's been left ever since old Mr. Hackett died." Despite the injunction, Mr. Blandings failed to stoop sufficiently; a beam dealt his head a vibrant blow on the same side that had suffered a few minutes ago from the door. But his dizziness left him in a moment and he was able to join his wife in the admiration she thought she was concealing by her silence.

The living room of the old Hackett house was not quite anything the Blandings had ever seen before. Another huge fireplace jutted from the massive central chimney; it would have dominated the room, Mrs. Blandings was certain, if it had not been so carefully boarded up, and the boards plastered over with the same wallpaper that ran around the room from ceiling to floor, covering all moldings and ornaments of the past. The wide oak planks of the floor, rounded and buckled here and there, and the magnificent hand-hewn beams, were obviously unchanged since Revolutionary times. But the furnishings were in general of the era of Benjamin Harrison, with an overlay of William McKinley, and here and there a final, crowning touch of Calvin Coolidge. There had been here no self-conscious restoration, no museum hand. The old house had been lived in through successive eras of changing custom and invention and usage and decoration; here was the residue, left when at last one final patriarch had died, and somehow that had been the end of a long story.

A square Checkering piano stood in one corner of the room as the Blandings surveyed it; a slimpsy and betasseled throw still carelessly draped across its shoulders. Its keys were not ivory, but mother-of-pearl, and a book bound in faded green boards stood on the music rack: 100 Songs All the World Loves. Two deeply tufted horsehair chairs were close by. One rested foursquare on its own feet; the other was a rocker that rocked not on the floor but on its own two tracks to which the rockers were held by an elaborate mechanism of tension springs, guide flanges, and curved restrainers, with which something was now badly askew. That was somebody's functionalism, once, thought Mr. Blandings, but without the depression that might normally have followed such an idea.

The Hacketts had been a music-loving family, apparently. A phonograph of the up-ended-casket type stood by a window, a record still on its turntable. To Mr. Blandings' amazement it revolved when he gave it a push, and when he lowered the rusty tone arm, complete with needle, onto the record groove, the room rustled for a minute with the sound as of a deaf-mute singing Dardanella through a funnel. Then something metallic ruptured inside the simulated mahogany, and all was still again.

Mrs. Blandings was too busy to reprove her husband, as she usually did, for meddling with what should better be left alone. She was moving in and out of a confusion of other furniture to gaze at an assortment of photographs on the walls: a large bright-tinted portrait, in an oval frame, of an elderly curmudgeon slicked up to the nines; thin, glistening white hair, a mustache with the curvature of a hay rake, a bulging green tie that sprang from the notch of a collar four inches high. Old Man Hackett, the last patriarch, Mrs. Blandings surmised. He was surrounded in other frames by what were apparently other members of his family, some cowed, some truculent. There was a family group in and surrounding a surrey that must have been the height of country style in the 1890's, and in the background could be seen, neat and perfect in a morning sun, the barns that now, on the other side of the road, presented only an aspect of ghostly ruin.

"They just moved out and left things this way when the old man died," said the real-estate man. "I never knew him, but he must have run a mighty smart farm. After they buried him, his wife and son moved back down into the valley, and the place has stayed this way ever since. You can see for yourself, that was around 1926."

He handed Mr. Blandings an old newspaper from the top of a vast pile of aging printed matter in one corner. It was yellow and heavy creased, and its date was June 2, 1926. Mr. Blandings studied it for a minute in the hope of finding something of deep significance, but it told him only that the Sesquicentennial Exposition had just opened in Philadelphia. When he turned it over, it snapped like a wafer in his hand.

"What sort of price is the owner asking for the property?" Mr. Blandings inquired. The sham of his casualness was apparent even to his wife, whose preoccupation with a papery wasp's nest behind a picture frame was itself no masterpiece.

The real-estate man's response was casual, too, but it had the benefit of twenty years of practice. "I think he's asking $15,000," he said, "but if you want my opinion, I think you could get it for less."

He turned a gaze of steady, manly frankness on Mrs. Blandings. "Maybe for a whole lot less," he said, very quietly, and with a smile that Mrs. Blandings knew he was not in the habit of using on everyone, "if he really took a shine to his prospective buyers."

Mrs. Blandings combined La Gioconda and Madame Récamier in her return gaze, and the real-estate man went on. "These country people, you know, they don't want to sell the places they and their families have lived in for a couple of hundred years to every Tom, Dick, and Harry that might come up from the city and flash a big bankroll on them. They have a lot of feeling about their places, and when they have to let them go, they want to see people get them that'll, you know, sort of want to carry on with them in the same spirit."

The smile the Blandings exchanged with the real-estate man was partly in gentle condescension of country people, partly in dissociation of themselves from all other city people who had ever before come up from New York to Lansdale County hunting for a quick bargain in real estate. It was a smile of perfect understanding.

The real-estate man let a little minute of silence go by, to mark the intimacy into which they had all so happily fallen. When he spoke again, it was as if he had put a precious instant away in his book of memories and was returning now, because he must, to mundane things.

"Let's go up the hill and take a look at your orchard," he said, clearing his throat. "There's a very interesting story connected with..."

The effect of the plural possessive pronoun was as a fiery liquor in Mr. and Mrs. Blandings' veins.

Copyright 1946 by Eric Hodgins

Copyright renewed © 1974 by Frank G. Jennings

The sweet old farmhouse burrowed into the upward slope of the land so deeply that you could enter either its bottom or middle floor at ground level. Its window trim was delicate and the lights in its sash were a bubbly amethyst. Its rooftree seemed to sway a little against the sky, and the massive chimney that rose out of it tilted a fraction to the south. Where the white paint was flecking off on the siding, there showed beneath it the faint blush of what must once have been a rich, dense red.

In front of it, rising and spreading along the whole length of the house, was the largest lilac tree that Mr. and Mrs. Blandings had ever seen. Its gnarled, rusty trunks rose intertwined to branch and taper into splays of this year's light young wood; they, in turn, burst into clouds of blossoms that made the whole vast thing a haze of blues and purples, billowed and wafting. When the house was new, the lilac must have been a shrub in the dooryard -- and house and shrub had gone on together, side by side since then. That was a hundred and seventy years ago, last April.

"If the lilac can live and be so old, so can the house," Mrs. Blandings said to herself. "It needs someone to love it, that's all." She flashed a glance at her husband, who flashed one back at her.

Using a penknife as a key, the real-estate man unlocked a lower door. As it swung back, the top hinge gave way and splashed in a brown powder on the floor. The door lurched against Mr. Blandings, and gave him a sharp crack on the forehead, but the damage was repaired in an instant, and Mr. Blandings, a handkerchief at his temple and his wife by his side, stood looking out through the amethyst window lights at an arc of beauty that made them both cry out. The land rushed downward to the river a mile away; then it rose again, layer after layer, plane after plane of hills and higher hills lighter beyond them. The air was luminous, and there were twenty shades of browns and greens in the plowed and wooded and folded earth.

"On a clear day you can see the Catskills," said the real-estate man.

Mr. and Mrs. Blandings were not such fools as to exclaim at this revelation. Mrs. Blandings flicked a glove in which a cobweb and free-running spider had become entangled; Mr. Blandings, his lips pursed and his eyes half closed, was a picture of controlled reserve; strong, realistic, poised. By the way the two of them said "Uh-huh?" with a rising inflection in perfect unison, the real-estate man knew that his sale was made. The offer would not come today, of course; it might, indeed, not come for a fortnight. But it would come; it would come with all the certainty of the equinox. He computed five per cent of $10,275 in his head and turned to the chimney footing.

"You'd have to do a little pointing up here," he said, indicating a compact but disorderly pile of stone in which a blackened hollow suggested a fireplace that had been in good working order at the time of the Treaty of Ghent. Mrs. Blandings, looking at the rubble, saw instead the kitchen of the Wayside Inn: a distaff plump with flax lying idly on the polished hearth; a tempered scale of copper pans and skillets pegged to hang heads downward near the oven wall; a bootjack in the corner and a shoat glistening on the spit.

What Mr. Blandings saw broke through into speech. "With a flagstone floor in here it'd be a nice place for a beer party on a Saturday night. You could put the keg right over in that corner."

He laughed a mild laugh which meant to say that if his thought was frivolous so, indeed, was the whole occasion that had called it forth. The notion that he might buy this old farmhouse, or any other, anywhere, ever, was light, gossamer nonsense; a whimsy; a caprice; it was his pleasure to give it a momentary fiction of solidity.

The real-estate man refused to take Mr. Blandings' suggestion so lightly. "You could at that," he said, awe and rumination mixed in his voice, as though he had just heard a brilliant restatement of nuclear theory. He quickly did five per cent of $11,550 in his head; aloud he said: "You haven't seen what's on the other side, either."

Mr. and Mrs. Blandings stepped across a mound of rubbish on the cold earthen floor and saw an even more impressive example of masonry in disarray. The second fireplace, loosely connected to the same flue as the first, stood at an angle with it that made a rough, bold V. Its stones were even more massive; hearth and manteltree were both huge monoliths. No frame of reference in all Euclid could be taken to which any major piece would be plumb, level, or square, but it was the work of a moment for Mr. Blandings to set everything to rights and swing a polished black kettle on its crane over the glowing ashes of an oak that he himself had sawn and quartered. In a moment he would have a mug of hot rum to banish the cold from his ten-mile plunge through the snowdrifts to rescue the heifer his hired man had abandoned for lost....

"They must have done their slaughtering down here years ago," said the real-estate man. "You don't see an old kettle like that every day in the week, not even in this part of the country."

The Blandings followed his forefinger and saw, on a circular pedestal of stone to the right of the hearth, a huge hemisphere of somber metal. Mr. Blandings thumped it lightly with his fist and it gave forth a hushed, whispering boom. "I think they filled that full of boiling water and scalded the hide off the pig before they dismembered him. Anyway, they must have hung their hams and bacon flitches on those hooks up there."

Mrs. Blandings, the membra disjecta of whose broiling chickens came to her kitchen packed into neat rectangles from the frozen-food store near her city apartment, contemplated the slaughtering of a 300-pound hog with ease, and observed the slender beauty of the hooks sunk deep in the old beams; hooks that had been shaped and pointed on some anvil lost in the tall grasses of a century ago.

"Mind your head as we make the turn," said the real-estate man, leading his prospects into a gloom in which a stairway could be faintly discerned. "I want you to see the living room just the way it's been left ever since old Mr. Hackett died." Despite the injunction, Mr. Blandings failed to stoop sufficiently; a beam dealt his head a vibrant blow on the same side that had suffered a few minutes ago from the door. But his dizziness left him in a moment and he was able to join his wife in the admiration she thought she was concealing by her silence.

The living room of the old Hackett house was not quite anything the Blandings had ever seen before. Another huge fireplace jutted from the massive central chimney; it would have dominated the room, Mrs. Blandings was certain, if it had not been so carefully boarded up, and the boards plastered over with the same wallpaper that ran around the room from ceiling to floor, covering all moldings and ornaments of the past. The wide oak planks of the floor, rounded and buckled here and there, and the magnificent hand-hewn beams, were obviously unchanged since Revolutionary times. But the furnishings were in general of the era of Benjamin Harrison, with an overlay of William McKinley, and here and there a final, crowning touch of Calvin Coolidge. There had been here no self-conscious restoration, no museum hand. The old house had been lived in through successive eras of changing custom and invention and usage and decoration; here was the residue, left when at last one final patriarch had died, and somehow that had been the end of a long story.

A square Checkering piano stood in one corner of the room as the Blandings surveyed it; a slimpsy and betasseled throw still carelessly draped across its shoulders. Its keys were not ivory, but mother-of-pearl, and a book bound in faded green boards stood on the music rack: 100 Songs All the World Loves. Two deeply tufted horsehair chairs were close by. One rested foursquare on its own feet; the other was a rocker that rocked not on the floor but on its own two tracks to which the rockers were held by an elaborate mechanism of tension springs, guide flanges, and curved restrainers, with which something was now badly askew. That was somebody's functionalism, once, thought Mr. Blandings, but without the depression that might normally have followed such an idea.

The Hacketts had been a music-loving family, apparently. A phonograph of the up-ended-casket type stood by a window, a record still on its turntable. To Mr. Blandings' amazement it revolved when he gave it a push, and when he lowered the rusty tone arm, complete with needle, onto the record groove, the room rustled for a minute with the sound as of a deaf-mute singing Dardanella through a funnel. Then something metallic ruptured inside the simulated mahogany, and all was still again.

Mrs. Blandings was too busy to reprove her husband, as she usually did, for meddling with what should better be left alone. She was moving in and out of a confusion of other furniture to gaze at an assortment of photographs on the walls: a large bright-tinted portrait, in an oval frame, of an elderly curmudgeon slicked up to the nines; thin, glistening white hair, a mustache with the curvature of a hay rake, a bulging green tie that sprang from the notch of a collar four inches high. Old Man Hackett, the last patriarch, Mrs. Blandings surmised. He was surrounded in other frames by what were apparently other members of his family, some cowed, some truculent. There was a family group in and surrounding a surrey that must have been the height of country style in the 1890's, and in the background could be seen, neat and perfect in a morning sun, the barns that now, on the other side of the road, presented only an aspect of ghostly ruin.

"They just moved out and left things this way when the old man died," said the real-estate man. "I never knew him, but he must have run a mighty smart farm. After they buried him, his wife and son moved back down into the valley, and the place has stayed this way ever since. You can see for yourself, that was around 1926."

He handed Mr. Blandings an old newspaper from the top of a vast pile of aging printed matter in one corner. It was yellow and heavy creased, and its date was June 2, 1926. Mr. Blandings studied it for a minute in the hope of finding something of deep significance, but it told him only that the Sesquicentennial Exposition had just opened in Philadelphia. When he turned it over, it snapped like a wafer in his hand.

"What sort of price is the owner asking for the property?" Mr. Blandings inquired. The sham of his casualness was apparent even to his wife, whose preoccupation with a papery wasp's nest behind a picture frame was itself no masterpiece.

The real-estate man's response was casual, too, but it had the benefit of twenty years of practice. "I think he's asking $15,000," he said, "but if you want my opinion, I think you could get it for less."

He turned a gaze of steady, manly frankness on Mrs. Blandings. "Maybe for a whole lot less," he said, very quietly, and with a smile that Mrs. Blandings knew he was not in the habit of using on everyone, "if he really took a shine to his prospective buyers."

Mrs. Blandings combined La Gioconda and Madame Récamier in her return gaze, and the real-estate man went on. "These country people, you know, they don't want to sell the places they and their families have lived in for a couple of hundred years to every Tom, Dick, and Harry that might come up from the city and flash a big bankroll on them. They have a lot of feeling about their places, and when they have to let them go, they want to see people get them that'll, you know, sort of want to carry on with them in the same spirit."

The smile the Blandings exchanged with the real-estate man was partly in gentle condescension of country people, partly in dissociation of themselves from all other city people who had ever before come up from New York to Lansdale County hunting for a quick bargain in real estate. It was a smile of perfect understanding.

The real-estate man let a little minute of silence go by, to mark the intimacy into which they had all so happily fallen. When he spoke again, it was as if he had put a precious instant away in his book of memories and was returning now, because he must, to mundane things.

"Let's go up the hill and take a look at your orchard," he said, clearing his throat. "There's a very interesting story connected with..."

The effect of the plural possessive pronoun was as a fiery liquor in Mr. and Mrs. Blandings' veins.

Copyright 1946 by Eric Hodgins

Copyright renewed © 1974 by Frank G. Jennings

Cuprins

Contents

BOOK ONE

I. The Real-Estate Man

II. Meeting of the Minds

III. The Deed

IV. First Lamp of Architecture

V. Second Lamp of Architecture

VI. Happy Interlude

VII. History Is as History Does

VIII. Plans and Elevations

IX. The Financial Angle

X. Bids

BOOK TWO

XI. Autumn Crocus

XII. Winter Week End

XIII. The Wind in the Windows

XIV. Extras

XV. Le Décor

XVI. Possession

XVII. Fulfillment

BOOK ONE

I. The Real-Estate Man

II. Meeting of the Minds

III. The Deed

IV. First Lamp of Architecture

V. Second Lamp of Architecture

VI. Happy Interlude

VII. History Is as History Does

VIII. Plans and Elevations

IX. The Financial Angle

X. Bids

BOOK TWO

XI. Autumn Crocus

XII. Winter Week End

XIII. The Wind in the Windows

XIV. Extras

XV. Le Décor

XVI. Possession

XVII. Fulfillment

Recenzii

"No ordinary jokesmith, Mr. Hodgins is light and expert."

-- The New York Times

"Anyone thinking of buying a home in the country (and who isn't?) should read this book for its practical lessons in real-estate values...the theme of unforeseen costs is sufficiently familiar to everyone to evoke nods of sympathy and smiles of understanding, especially when Mr. Blandings, in a fitting climax, faced a damage suit for intimating that one of his earlier architects had shown poor taste."

-- The Christian Science Monitor

"Mr. Blandings' skinning by real-estate men, architects, contractors, and plumbers should provide the reader with a lot of sadistic satisfaction, if it isn't too uncomfortably reminiscent."

-- The New Yorker

-- The New York Times

"Anyone thinking of buying a home in the country (and who isn't?) should read this book for its practical lessons in real-estate values...the theme of unforeseen costs is sufficiently familiar to everyone to evoke nods of sympathy and smiles of understanding, especially when Mr. Blandings, in a fitting climax, faced a damage suit for intimating that one of his earlier architects had shown poor taste."

-- The Christian Science Monitor

"Mr. Blandings' skinning by real-estate men, architects, contractors, and plumbers should provide the reader with a lot of sadistic satisfaction, if it isn't too uncomfortably reminiscent."

-- The New Yorker