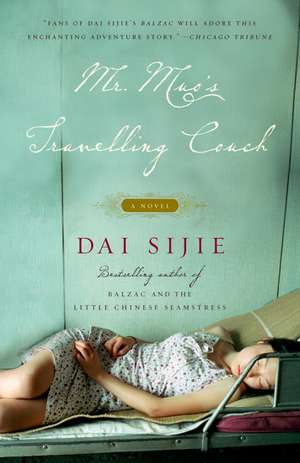

Mr. Muo's Travelling Couch

Autor Dai Sijie Traducere de Ina Rilkeen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mai 2006

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

Listen Up (2005)

This may prove difficult in a China that has embraced western sexual mores along with capitalism–especially since Muo, while indisputably a romantic, is no ladies’ man. Tender, laugh-out-loud funny, and unexpectedly wise, Mr. Muo’s Travelling Couch introduces a hero as endearingly inept as Inspector Clouseau and as valiant as Don Quixote.

Preț: 81.47 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 122

Preț estimativ în valută:

15.59€ • 16.26$ • 12.96£

15.59€ • 16.26$ • 12.96£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400077144

ISBN-10: 1400077141

Pagini: 287

Dimensiuni: 133 x 204 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

ISBN-10: 1400077141

Pagini: 287

Dimensiuni: 133 x 204 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

Notă biografică

Dai Sijie is a Chinese-born filmmaker and novelist who has lived and worked in France since 1984. His first novel, Balzac and the Little Chinese Seamstress, was an overnight sensation; it spent twenty-three weeks on the New York Times best-seller list.

Extras

A Disciple of Freud

The metal chain sheathed in transparent pink plastic is reflected, like a gleaming snake, in the window of the railway carriage, beyond which the signals fade to pinpoints of emerald and ruby before being swallowed up in the mist of a sultry night in July.

(Only a short while ago, in the squalid restaurant of a little station near the Yellow Mountain, this same chain had been looped around the leg of a fake-mahogany table and the retractable chrome-plated handle of a pale blue Delsey suitcase on wheels belonging to one Mr. Muo, a Chinese-born apprentice in psychoanalysis recently returned from France.)

For a man so bereft of charm and good looks, thin and scrawny, a scant five foot three, with an unruly shock of hair and bulging eyes slightly squinty behind thick lenses, Mr. Muo moves with surprising assurance: he takes off his French-made shoes, revealing red socks (the left one with a hole, through which pokes a bony toe, pale as skimmed milk), then climbs up on the wooden seat (a sort of banquette deprived of padding) to stow his Delsey on the luggage rack; he attaches the chain by passing the hoop of a small padlock through the links on either end, and rises up on tiptoe to confirm that the lock is secure.

Having settled on the bench, he stashes his shoes under the seat, dons a pair of white flip-flops, wipes his glasses, and, lighting a small cigar, uncaps his pen and gets to work-that is to say, he begins noting down dreams in a school exercise book purchased in France, this discipline being part of his self-imposed training as a psychoanalyst. Hardly has the train gathered speed when the hard-seat carriage (the only one for which tickets were still available) is bustling with peasant women carrying large baskets and bamboo panniers, plying their modest trade between stations, lurching up and down the aisles, some with hard-boiled eggs and sweet dumplings, others with fruit, cigarettes, cans of cola, Chinese mineral water, and even bottles of Evian. Uniformed railway staff work their way down the crowded carriage pushing trolleys laden with spicy ducks' feet, peppered spare ribs, newspapers and scandal sheets. An urchin of no more than ten is sitting on the floor, vigorously applying polish to the stiletto heel of a woman of some mystery, remarkable on this night train for her oversized, dark blue sunglasses. No one notices Mr. Muo or the maniacal attention he accords his Delsey 2000. But once he becomes engrossed in his writing, he is oblivious to the world. Travelling on a day train a few days ago-likewise in a carriage with hard seats-he had just completed his daily entries with a resounding quote from Lacan when looking up he observed a trio of passengers so intrigued by his security measures that they had mounted the bench for a better look. They were gesturing dramatically in double time, as in a silent movie.

Tonight, his right-hand neighbour on the three-seater bench, a dapper fifty-year-old with sagging shoulders and a long, swarthy face, keeps glancing at the exercise book, covertly at first, but then quite brazenly.

"Mr. Four Eyes," he enquires, in a tone more obsequious than his rude address would imply, "is that English you're writing?" Then: "May I trouble you for some advice? My son, a secondary-school pupil, is utterly hopeless-hopeless-at English."

"By all means," Muo replies with a serious air, not in the least offended by the moniker. "Let me tell you about Voltaire, a French eighteenth-century philosopher. One day Boswell asked him, 'Do you speak English?' and Voltaire replied, 'Speaking English requires placing the tip of the tongue against the front teeth. Me, I am too old for that; I have no teeth left.' Do you follow? He was referring to the way the th is pronounced. The same goes for me: my teeth aren't long enough for the language of globalisation, although there are certain English writers whom I revere, and also one or two Americans. However, what I am writing, sir, is French."

Initially awed by this reply, his neighbour quickly composes himself and fixes Muo with a look of profound loathing. Like all workers of the revolutionary period, he can't abide those whose learning surpasses his own and who, by virtue of superior knowledge, symbolise enormous power. Thinking to give Muo a lesson in modesty, he draws a game of Chinese checkers from his bag and invites him to play.

"So sorry," says Muo, in all earnestness, "I don't play. But I do know exactly how the game originated. I know where it came from and when it was invented . . ."

Now completely nonplussed, the man asks, before settling down to sleep, "Is it true that you are writing in French?"

"Indeed it is."

"Ah, French!" he intones several times, his words echoing in the silence of the night train, the tone of satisfied comprehension belying the complete bewilderment on the face of this solid family man.

For the past eleven years Muo has been living in Paris, a seventh-floor flat, that is to say, a converted maid's room (a walk-up, with the red carpet on the stairs stopping at the sixth floor), a damp place with cracks all over the ceiling and the walls. He spends every night from eleven till six in the morning noting down dreams-first his own, then those of others, too. He composes his notes in French, using a Larousse dictionary to check each word he is unsure of. And how many exercise books he has filled already! He keeps them all in shoe boxes secured with rubber bands, stacked on a metal e´tage`re-dust-covered boxes, like those in which the French invariably keep their utility bills, pay stubs, tax forms, bank statements, insurance policies, schedules of instalment plan payments, and builders' receipts: in other words, the type of boxes that contain the records of a lifetime. (He himself has just turned forty-the age of lucidity, according to the old sage Confucius.

In the decade since his arrival in Paris in 1989 Muo had been recording these dreams in a French mined painstakingly from Larousse, when suddenly he found himself changed-changed no less than his wire-framed spectacles (like those of the last emperor in Bertolucci's film), stained with yellow grease, clouded with sweat, and so twisted that they no longer fit in any spectacle case. "I wonder if my head has changed shape, too," he noted in his exercise book after the Chinese New Year celebrations of the year 2000. That day, tying an apron around his waist and rolling up his sleeves, he resolved to tidy his garret. He was doing the dishes, which had been stacked in the sink for days (such a bad bachelor's habit), a solemn mass jutting iceberg-like from the soapy surface, when his glasses slipped from his nose-plop!-into the murky water, on which floated tea leaves and food scraps, above the reefs of crockery. He groped for them blindly under the suds, fishing out chopsticks, rusty saucepans encrusted with rice, tea cups, a glass ashtray, rinds of sugar melon and watermelon, moldy bowls, chipped plates, spoons, and a couple of forks so greasy they slipped from his grasp and clattered to the floor. At last, he found his spectacles. He carefully wiped off the suds and polished the lenses before holding them up for inspection: there were fine new scratches among the old ones, and the sides, already bent, were now a sculpture twisted beyond recognition. But all in all they were fine.

Tonight, as this Chinese train pursues its inexorable journey, neither the hardness of the seat nor the press of his fellow passengers seems to bother him. Nor is he distracted by the alluring passenger in oversized sunglasses (a showbiz wannabe travelling incognito, perhaps?), sitting by the opposite window beside a young couple and across from three elderly women. She is graciously tilting her head in his direction while resting her elbow on the folding table. But no indeed, neither train nor intriguing stranger can offer our Mr. Muo such transport as he finds this moment in words and writing, the language of a distant land and especially of his dreams, which he records and analyses with professional rigour and zeal, not to say loving tenderness.

Now and then his face lights up with pleasure, especially as he recalls or applies a phrase, perhaps even an entire paragraph, of Freud or Lacan, the two masters for whom his esteem is boundless. As though recognising a long-lost friend, he smiles and moves his lips with childish glee. His expression, so severe just a moment ago, softens like parched earth under a shower; his facial muscles slacken; his eyes grow moist and limpid. Freed from the constraints of classical calligraphy, his writing has become a confident Western scrawl, with strokes growing bolder and bolder and loops ranging from dainty to tall, undulating, and harmonious. This is a sign of his entry into another world, a world ever in motion, ever fascinating, ever new.

When a change in the train's speed interrupts his writing, he lifts his head (his true Chinese head, always on guard) and casts a cautious eye overhead to make sure his suitcase is still attached to the luggage rack. In the same reflex, and still in a state of alert, he feels inside his jacket for his Chinese passport, his French residency permit, and his credit card in the zippered pocket. Then, more discreetly, he moves his hand to the back of his trousers and runs his fingertips over the bump produced by the stash in his underpants, where he has secreted the not-inconsiderable sum of ten thousand dollars, cash.

Toward midnight the strip lights are switched off. Everyone in the packed carriage is asleep, except for three or four card players squatting by the door of the toilet. Bills continually change hands amid the feverish bets. Under the naked bulb of the night-light, whose weak blue glow casts violet shadows across their faces, the players hold cards fanned close to their chests as an empty beer can rolls this way and that. Muo recaps his pen, places his exercise book on the folding table, and observes the attractive lady who, in the semidarkness, has removed her wraparound sunglasses and is smearing a bluish cream on her face. How vain she is, he reflects. How China has changed! At regular intervals the woman turns to the window to behold her reflection, before removing the bluish unguent and starting all over again. It has to be said, the mask gives her the sphinxlike aspect of a femme fatale as she studies her face in the glass. But when a passing train flashes a succession of lights on the window, Muo observes that she is crying. Tears stream down on either side of her nose, defining wonderful, sinuous pathways in the thick, bluish mask.

From the Hardcover edition.

The metal chain sheathed in transparent pink plastic is reflected, like a gleaming snake, in the window of the railway carriage, beyond which the signals fade to pinpoints of emerald and ruby before being swallowed up in the mist of a sultry night in July.

(Only a short while ago, in the squalid restaurant of a little station near the Yellow Mountain, this same chain had been looped around the leg of a fake-mahogany table and the retractable chrome-plated handle of a pale blue Delsey suitcase on wheels belonging to one Mr. Muo, a Chinese-born apprentice in psychoanalysis recently returned from France.)

For a man so bereft of charm and good looks, thin and scrawny, a scant five foot three, with an unruly shock of hair and bulging eyes slightly squinty behind thick lenses, Mr. Muo moves with surprising assurance: he takes off his French-made shoes, revealing red socks (the left one with a hole, through which pokes a bony toe, pale as skimmed milk), then climbs up on the wooden seat (a sort of banquette deprived of padding) to stow his Delsey on the luggage rack; he attaches the chain by passing the hoop of a small padlock through the links on either end, and rises up on tiptoe to confirm that the lock is secure.

Having settled on the bench, he stashes his shoes under the seat, dons a pair of white flip-flops, wipes his glasses, and, lighting a small cigar, uncaps his pen and gets to work-that is to say, he begins noting down dreams in a school exercise book purchased in France, this discipline being part of his self-imposed training as a psychoanalyst. Hardly has the train gathered speed when the hard-seat carriage (the only one for which tickets were still available) is bustling with peasant women carrying large baskets and bamboo panniers, plying their modest trade between stations, lurching up and down the aisles, some with hard-boiled eggs and sweet dumplings, others with fruit, cigarettes, cans of cola, Chinese mineral water, and even bottles of Evian. Uniformed railway staff work their way down the crowded carriage pushing trolleys laden with spicy ducks' feet, peppered spare ribs, newspapers and scandal sheets. An urchin of no more than ten is sitting on the floor, vigorously applying polish to the stiletto heel of a woman of some mystery, remarkable on this night train for her oversized, dark blue sunglasses. No one notices Mr. Muo or the maniacal attention he accords his Delsey 2000. But once he becomes engrossed in his writing, he is oblivious to the world. Travelling on a day train a few days ago-likewise in a carriage with hard seats-he had just completed his daily entries with a resounding quote from Lacan when looking up he observed a trio of passengers so intrigued by his security measures that they had mounted the bench for a better look. They were gesturing dramatically in double time, as in a silent movie.

Tonight, his right-hand neighbour on the three-seater bench, a dapper fifty-year-old with sagging shoulders and a long, swarthy face, keeps glancing at the exercise book, covertly at first, but then quite brazenly.

"Mr. Four Eyes," he enquires, in a tone more obsequious than his rude address would imply, "is that English you're writing?" Then: "May I trouble you for some advice? My son, a secondary-school pupil, is utterly hopeless-hopeless-at English."

"By all means," Muo replies with a serious air, not in the least offended by the moniker. "Let me tell you about Voltaire, a French eighteenth-century philosopher. One day Boswell asked him, 'Do you speak English?' and Voltaire replied, 'Speaking English requires placing the tip of the tongue against the front teeth. Me, I am too old for that; I have no teeth left.' Do you follow? He was referring to the way the th is pronounced. The same goes for me: my teeth aren't long enough for the language of globalisation, although there are certain English writers whom I revere, and also one or two Americans. However, what I am writing, sir, is French."

Initially awed by this reply, his neighbour quickly composes himself and fixes Muo with a look of profound loathing. Like all workers of the revolutionary period, he can't abide those whose learning surpasses his own and who, by virtue of superior knowledge, symbolise enormous power. Thinking to give Muo a lesson in modesty, he draws a game of Chinese checkers from his bag and invites him to play.

"So sorry," says Muo, in all earnestness, "I don't play. But I do know exactly how the game originated. I know where it came from and when it was invented . . ."

Now completely nonplussed, the man asks, before settling down to sleep, "Is it true that you are writing in French?"

"Indeed it is."

"Ah, French!" he intones several times, his words echoing in the silence of the night train, the tone of satisfied comprehension belying the complete bewilderment on the face of this solid family man.

For the past eleven years Muo has been living in Paris, a seventh-floor flat, that is to say, a converted maid's room (a walk-up, with the red carpet on the stairs stopping at the sixth floor), a damp place with cracks all over the ceiling and the walls. He spends every night from eleven till six in the morning noting down dreams-first his own, then those of others, too. He composes his notes in French, using a Larousse dictionary to check each word he is unsure of. And how many exercise books he has filled already! He keeps them all in shoe boxes secured with rubber bands, stacked on a metal e´tage`re-dust-covered boxes, like those in which the French invariably keep their utility bills, pay stubs, tax forms, bank statements, insurance policies, schedules of instalment plan payments, and builders' receipts: in other words, the type of boxes that contain the records of a lifetime. (He himself has just turned forty-the age of lucidity, according to the old sage Confucius.

In the decade since his arrival in Paris in 1989 Muo had been recording these dreams in a French mined painstakingly from Larousse, when suddenly he found himself changed-changed no less than his wire-framed spectacles (like those of the last emperor in Bertolucci's film), stained with yellow grease, clouded with sweat, and so twisted that they no longer fit in any spectacle case. "I wonder if my head has changed shape, too," he noted in his exercise book after the Chinese New Year celebrations of the year 2000. That day, tying an apron around his waist and rolling up his sleeves, he resolved to tidy his garret. He was doing the dishes, which had been stacked in the sink for days (such a bad bachelor's habit), a solemn mass jutting iceberg-like from the soapy surface, when his glasses slipped from his nose-plop!-into the murky water, on which floated tea leaves and food scraps, above the reefs of crockery. He groped for them blindly under the suds, fishing out chopsticks, rusty saucepans encrusted with rice, tea cups, a glass ashtray, rinds of sugar melon and watermelon, moldy bowls, chipped plates, spoons, and a couple of forks so greasy they slipped from his grasp and clattered to the floor. At last, he found his spectacles. He carefully wiped off the suds and polished the lenses before holding them up for inspection: there were fine new scratches among the old ones, and the sides, already bent, were now a sculpture twisted beyond recognition. But all in all they were fine.

Tonight, as this Chinese train pursues its inexorable journey, neither the hardness of the seat nor the press of his fellow passengers seems to bother him. Nor is he distracted by the alluring passenger in oversized sunglasses (a showbiz wannabe travelling incognito, perhaps?), sitting by the opposite window beside a young couple and across from three elderly women. She is graciously tilting her head in his direction while resting her elbow on the folding table. But no indeed, neither train nor intriguing stranger can offer our Mr. Muo such transport as he finds this moment in words and writing, the language of a distant land and especially of his dreams, which he records and analyses with professional rigour and zeal, not to say loving tenderness.

Now and then his face lights up with pleasure, especially as he recalls or applies a phrase, perhaps even an entire paragraph, of Freud or Lacan, the two masters for whom his esteem is boundless. As though recognising a long-lost friend, he smiles and moves his lips with childish glee. His expression, so severe just a moment ago, softens like parched earth under a shower; his facial muscles slacken; his eyes grow moist and limpid. Freed from the constraints of classical calligraphy, his writing has become a confident Western scrawl, with strokes growing bolder and bolder and loops ranging from dainty to tall, undulating, and harmonious. This is a sign of his entry into another world, a world ever in motion, ever fascinating, ever new.

When a change in the train's speed interrupts his writing, he lifts his head (his true Chinese head, always on guard) and casts a cautious eye overhead to make sure his suitcase is still attached to the luggage rack. In the same reflex, and still in a state of alert, he feels inside his jacket for his Chinese passport, his French residency permit, and his credit card in the zippered pocket. Then, more discreetly, he moves his hand to the back of his trousers and runs his fingertips over the bump produced by the stash in his underpants, where he has secreted the not-inconsiderable sum of ten thousand dollars, cash.

Toward midnight the strip lights are switched off. Everyone in the packed carriage is asleep, except for three or four card players squatting by the door of the toilet. Bills continually change hands amid the feverish bets. Under the naked bulb of the night-light, whose weak blue glow casts violet shadows across their faces, the players hold cards fanned close to their chests as an empty beer can rolls this way and that. Muo recaps his pen, places his exercise book on the folding table, and observes the attractive lady who, in the semidarkness, has removed her wraparound sunglasses and is smearing a bluish cream on her face. How vain she is, he reflects. How China has changed! At regular intervals the woman turns to the window to behold her reflection, before removing the bluish unguent and starting all over again. It has to be said, the mask gives her the sphinxlike aspect of a femme fatale as she studies her face in the glass. But when a passing train flashes a succession of lights on the window, Muo observes that she is crying. Tears stream down on either side of her nose, defining wonderful, sinuous pathways in the thick, bluish mask.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

"Fans of Dai Sijie's Balzac will adore this enchanting adventure story." —Chicago Tribune

“Always entertaining. . . . A bawdy, comic romp [that] takes our hero into all kinds of wild scrapes and adventures.” —San Francisco Chronicle

"Poignant. . . . Hilarious. . . . A fascinating book." —San Jose Mercury News

“Always entertaining. . . . A bawdy, comic romp [that] takes our hero into all kinds of wild scrapes and adventures.” —San Francisco Chronicle

"Poignant. . . . Hilarious. . . . A fascinating book." —San Jose Mercury News

Descriere

After years of studying Freud in Paris, Mr. Muo returns home to introduce the blessings of psychoanalysis to 21st-century China. But it is his hidden purpose to liberate his university sweetheart--now a political prisoner--that leads him to the sadistic local magistrate who demands a virgin maiden in exchange for his sweetheart's freedom.

Premii

- Listen Up Editor's Choice, 2005