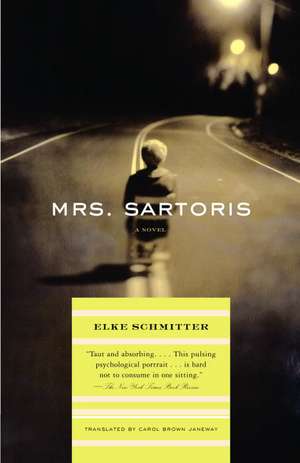

Mrs. Sartoris

Autor Elke Schmitteren Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 noi 2004

Margarethe can remember very clearly the last time she was happy: she was eighteen, prized for her beauty, and swept off her feet by her wealthy, dashing boyfriend. Then he left her. For the last twenty years she has lived in a provincial German town with her dependable husband, her self-directed daughter, and her adoring mother-in-law. Her life has been one of numbing predictability–until she meets Michael, a married man who stirs her from her resignation, delivering her to heights of rapture only to ignite far more destructive passions. An erotic, psychologically charged thriller narrated with chilling dispassion, Mrs. Sartoris opens a bracing portal onto obsession and the crucible of love.

Preț: 68.24 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 102

Preț estimativ în valută:

13.06€ • 14.18$ • 10.97£

13.06€ • 14.18$ • 10.97£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780375726149

ISBN-10: 0375726144

Pagini: 160

Dimensiuni: 132 x 203 x 11 mm

Greutate: 0.15 kg

Editura: Vintage

ISBN-10: 0375726144

Pagini: 160

Dimensiuni: 132 x 203 x 11 mm

Greutate: 0.15 kg

Editura: Vintage

Notă biografică

Elke Schmitter was born in 1961 in Krefeld, Germany, and studied philosophy in Munich. As a journalist she writes for Der Spiegel. Her first novel, Mrs. Sartoris, has been translated into thirteen languages. Her second novel, Minor Misdemeanors, was published in Germany in 2002. She lives in Berlin with her family.

Extras

The street was empty. It was drizzling, as it often did in this region, and twilight was giving way to darkness—so you can’t say that the visibility was good. Perhaps that’s why I was so late in spotting him, but it was also probably because I was deep in thought. I’m often deep in thought. Not that anything comes of it.

I was on the way home. I had been shopping in the town and had met Renate, who had come over to L. for the afternoon. We had a drink, really just one—two at the most. I knew I would be driving, and besides, Ernst checks my breath. Sometimes he does it for some reason that may have nothing to do with me. He comes out to meet me before I reach the front door, to relieve me of the shopping bags or some other excuse. He strokes my cheek with a kiss, inhaling deeply along the way. He doesn’t know I figured it out long ago, because he prides himself on using his knowledge discreetly. This means he doesn’t reproach me immediately. He bides his time, even if it’s only for a minute—however long it takes me to make an excuse and get through the door. Or skip the excuse, if we’re alone.

So I didn’t drink a lot. Maybe one, two sherries. If you’re a wine drinker, the only thing they serve in Hirmer’s Café is a Moselle, because Hirmer Senior, when he opened the place more than ninety years ago, was a Moselle fanatic, which was quite common back then. It’s a big wine, and too sweet for us these days, and sweet isn’t even the right word. There’s something too full-bodied about it, it’s too heavy to drink with anything except meat in aspic, and they no longer serve meat in aspic at Hirmer’s either. So when we’re there, Renate and I drink sherry. It tastes okay going down, and it’s cheap compared with Campari or other respectable drinks. We can hardly drink schnapps, because we’re in L. after all, and I live here, and when a lady lives here, if she ever feels like having a drink for no reason and she’s not part of some group, she orders sherry.

The first time I saw her was in Dr. Lehmkuhl’s waiting room. Dr. Lehmkuhl’s grandfather still had a big farm outside town, his father had been the first interim mayor after the war, and he himself had a major repu- tation as a neurologist. I was there because my nerves were in a state—or more precisely, because Irmi and Ernst had noticed. I set off in the car to buy bread and soap powder and came back with cigarettes, which Ernst gave up ten years ago. I forgot my godchildren’s birthdays and pulled up the marigolds I’d sowed in the garden myself, because I mistook the stalks for weeds. Twice I suffered every housewife’s nightmare of leaving the burner of the stove on with an empty pot on top. There are apparently electric stoves you can get now that switch themselves off before the pot melts and there’s a catastrophe. But we had an old one, because that’s what Irmi manages best. She has her head together as well.

The two of them decided something was the matter with me. And they were right. That I slept badly at night and sometimes dozed off in the early evening on the sofa was nothing new. I could even make Ernst believe it had always been like that. He didn’t know that I often woke up at one-thirty in the night and lay awake till morning, doggedly watching the peregrinations of the hands round the face of the alarm clock. The hands glow in the dark; the clock was a honeymoon present from Irmi. Things like that were incredibly modern back then and also much better made. The clock will outlive us all.

But the state of my nerves was something new to them. Both of them claimed they were worried about me, and I actually believed it of Irmi. Their conversations would sometimes break off when I came into the living room, or Irmi would lower her voice when she was talking to Ernst in her room. Eventually their verdict was unanimous: I was going to harm myself. They couldn’t very well involve Daniela; she was already quite independent for her age and didn’t let herself be told much anyway—unless she wanted to get permission to spend the night at a friend’s house.

So an appointment was made with Dr. Lehmkuhl, and I went—I didn’t even put up a fight.

When it came right down to it, I didn’t care one way or the other, and the thought of someone taking care of me was an appealing one. There was a woman sitting in the waiting room who was around my age, clothes a little loud, expensive jewelry on both wrists, and the kind of subtle tan that signals regular skin care and sessions with a sunlamp. I didn’t know her by sight, which in a town like L. is quite a surprise. Sooner or later you meet someone like that at the theater, or at a coffee morning or one of Ernst’s club evenings. She thumbed through magazines, glancing up periodically at the clock, and then sighed so heavily that it would almost have been impolite not to react. We exchanged a glance, and she asked in a deep, very attractive voice if one always had to wait so long here. I said this was my first visit too, and that’s how we fell into conversation. Although she didn’t know anyone in town, she didn’t seem to be lonely or afflicted in any way, on the contrary she radiated energy. When the nurse finally came into the waiting room to make apologies for Dr. Lehmkuhl—he had been called out on an emergency and unfortunately would not be back at the practice before the end of the day—she collected her things abruptly, put a wonderful lightweight pale summer coat over her arm, and invited me to a cup of coffee: the afternoon was wasted anyway, so why didn’t we make something out of it? And so we did. When I came home after dinner, Irmi and Ernst stared at me in amazement. They were probably asking themselves if Dr. Lehmkuhl had dispensed neat alcohol by way of a prelude to his treatment. But it wasn’t Dr. Lehmkuhl, it was my friend Renate. And it wasn’t neat alcohol, it was a very good red wine. Good for the blood vessels, at least.

Further appointments were made, of course. I liked Dr. Lehmkuhl right away. A sinewy man, obviously a tennis player; he emanated self-control and rigor, which impressed me. I immediately told him more about myself than Irmi and Ernst will ever know; he listened patiently and without emotion, but in such a way that I knew I was understood. He did some tests—tapping the kneecaps, tickling the soles of the feet, etc.—with care but a lack of enthusiasm that conveyed a belief, which I shared, that there was nothing to be learned from them. He asked me about drinking—perhaps Ernst had put him onto this—and I lied to him with an equanimity born of long practice. Much later, I poured him red wine, straight up. It was fun to watch him shake his head and to know that his helplessness was tinged with fellow-feeling. He had certainly noticed my talent for being able, at will, to seem healthy or sick, energetic or frail, aggressive or sweet, as circumstances required, and yet he also sensed that I didn’t want to play games with him. I didn’t want to lose his attention, and that involved being honest with him—up to a point.

He gave me pills. He did it unwillingly, as he told me, but because I refused to switch to one of his colleagues who was a psychotherapist—I was perfectly aware why this would be a bad idea—it seemed to him the only way to help me for the moment. I took the first dose in his office, and I can still remember the feeling of armor-plated protection I had when I got home. I was more alert than usual; I emptied the ashtrays, said good night to Daniela in her room, and left the car key in the exact place where Ernst always wanted it left. I was enjoying myself along the way, watching myself doing all this and congratulating myself the way we used to congratulate the poodle when he came to us carrying his bowl in his mouth. My imperturbability seemed strange even to me, and when Ernst asked me how I felt, I said: the same way our car feels right after it’s been inspected. For him, my visit to the doctor had its desired effect: I was functioning again. If only for that first evening.

Because I didn’t get the prescription filled. I decided to pull myself together, and it went reasonably well. I wanted to go back to Dr. Lehmkuhl, but I wanted to get through the days without some official inspection sticker saying I was okay. There were times when I dealt with the whole daily round—getting my child to kindergarten and the school, making two meals a day and serving them at set times, shopping, doing the garden, organizing children’s birthdays, appearing at club evenings, doing holidays, doing bookkeeping and finances, hairdresser’s appointments and obedience school for the dog, doing Easters and Christmases and on and on—I dealt with the whole thing as if it went without saying. And that wasn’t really the problem anyway.

From the Hardcover edition.

I was on the way home. I had been shopping in the town and had met Renate, who had come over to L. for the afternoon. We had a drink, really just one—two at the most. I knew I would be driving, and besides, Ernst checks my breath. Sometimes he does it for some reason that may have nothing to do with me. He comes out to meet me before I reach the front door, to relieve me of the shopping bags or some other excuse. He strokes my cheek with a kiss, inhaling deeply along the way. He doesn’t know I figured it out long ago, because he prides himself on using his knowledge discreetly. This means he doesn’t reproach me immediately. He bides his time, even if it’s only for a minute—however long it takes me to make an excuse and get through the door. Or skip the excuse, if we’re alone.

So I didn’t drink a lot. Maybe one, two sherries. If you’re a wine drinker, the only thing they serve in Hirmer’s Café is a Moselle, because Hirmer Senior, when he opened the place more than ninety years ago, was a Moselle fanatic, which was quite common back then. It’s a big wine, and too sweet for us these days, and sweet isn’t even the right word. There’s something too full-bodied about it, it’s too heavy to drink with anything except meat in aspic, and they no longer serve meat in aspic at Hirmer’s either. So when we’re there, Renate and I drink sherry. It tastes okay going down, and it’s cheap compared with Campari or other respectable drinks. We can hardly drink schnapps, because we’re in L. after all, and I live here, and when a lady lives here, if she ever feels like having a drink for no reason and she’s not part of some group, she orders sherry.

The first time I saw her was in Dr. Lehmkuhl’s waiting room. Dr. Lehmkuhl’s grandfather still had a big farm outside town, his father had been the first interim mayor after the war, and he himself had a major repu- tation as a neurologist. I was there because my nerves were in a state—or more precisely, because Irmi and Ernst had noticed. I set off in the car to buy bread and soap powder and came back with cigarettes, which Ernst gave up ten years ago. I forgot my godchildren’s birthdays and pulled up the marigolds I’d sowed in the garden myself, because I mistook the stalks for weeds. Twice I suffered every housewife’s nightmare of leaving the burner of the stove on with an empty pot on top. There are apparently electric stoves you can get now that switch themselves off before the pot melts and there’s a catastrophe. But we had an old one, because that’s what Irmi manages best. She has her head together as well.

The two of them decided something was the matter with me. And they were right. That I slept badly at night and sometimes dozed off in the early evening on the sofa was nothing new. I could even make Ernst believe it had always been like that. He didn’t know that I often woke up at one-thirty in the night and lay awake till morning, doggedly watching the peregrinations of the hands round the face of the alarm clock. The hands glow in the dark; the clock was a honeymoon present from Irmi. Things like that were incredibly modern back then and also much better made. The clock will outlive us all.

But the state of my nerves was something new to them. Both of them claimed they were worried about me, and I actually believed it of Irmi. Their conversations would sometimes break off when I came into the living room, or Irmi would lower her voice when she was talking to Ernst in her room. Eventually their verdict was unanimous: I was going to harm myself. They couldn’t very well involve Daniela; she was already quite independent for her age and didn’t let herself be told much anyway—unless she wanted to get permission to spend the night at a friend’s house.

So an appointment was made with Dr. Lehmkuhl, and I went—I didn’t even put up a fight.

When it came right down to it, I didn’t care one way or the other, and the thought of someone taking care of me was an appealing one. There was a woman sitting in the waiting room who was around my age, clothes a little loud, expensive jewelry on both wrists, and the kind of subtle tan that signals regular skin care and sessions with a sunlamp. I didn’t know her by sight, which in a town like L. is quite a surprise. Sooner or later you meet someone like that at the theater, or at a coffee morning or one of Ernst’s club evenings. She thumbed through magazines, glancing up periodically at the clock, and then sighed so heavily that it would almost have been impolite not to react. We exchanged a glance, and she asked in a deep, very attractive voice if one always had to wait so long here. I said this was my first visit too, and that’s how we fell into conversation. Although she didn’t know anyone in town, she didn’t seem to be lonely or afflicted in any way, on the contrary she radiated energy. When the nurse finally came into the waiting room to make apologies for Dr. Lehmkuhl—he had been called out on an emergency and unfortunately would not be back at the practice before the end of the day—she collected her things abruptly, put a wonderful lightweight pale summer coat over her arm, and invited me to a cup of coffee: the afternoon was wasted anyway, so why didn’t we make something out of it? And so we did. When I came home after dinner, Irmi and Ernst stared at me in amazement. They were probably asking themselves if Dr. Lehmkuhl had dispensed neat alcohol by way of a prelude to his treatment. But it wasn’t Dr. Lehmkuhl, it was my friend Renate. And it wasn’t neat alcohol, it was a very good red wine. Good for the blood vessels, at least.

Further appointments were made, of course. I liked Dr. Lehmkuhl right away. A sinewy man, obviously a tennis player; he emanated self-control and rigor, which impressed me. I immediately told him more about myself than Irmi and Ernst will ever know; he listened patiently and without emotion, but in such a way that I knew I was understood. He did some tests—tapping the kneecaps, tickling the soles of the feet, etc.—with care but a lack of enthusiasm that conveyed a belief, which I shared, that there was nothing to be learned from them. He asked me about drinking—perhaps Ernst had put him onto this—and I lied to him with an equanimity born of long practice. Much later, I poured him red wine, straight up. It was fun to watch him shake his head and to know that his helplessness was tinged with fellow-feeling. He had certainly noticed my talent for being able, at will, to seem healthy or sick, energetic or frail, aggressive or sweet, as circumstances required, and yet he also sensed that I didn’t want to play games with him. I didn’t want to lose his attention, and that involved being honest with him—up to a point.

He gave me pills. He did it unwillingly, as he told me, but because I refused to switch to one of his colleagues who was a psychotherapist—I was perfectly aware why this would be a bad idea—it seemed to him the only way to help me for the moment. I took the first dose in his office, and I can still remember the feeling of armor-plated protection I had when I got home. I was more alert than usual; I emptied the ashtrays, said good night to Daniela in her room, and left the car key in the exact place where Ernst always wanted it left. I was enjoying myself along the way, watching myself doing all this and congratulating myself the way we used to congratulate the poodle when he came to us carrying his bowl in his mouth. My imperturbability seemed strange even to me, and when Ernst asked me how I felt, I said: the same way our car feels right after it’s been inspected. For him, my visit to the doctor had its desired effect: I was functioning again. If only for that first evening.

Because I didn’t get the prescription filled. I decided to pull myself together, and it went reasonably well. I wanted to go back to Dr. Lehmkuhl, but I wanted to get through the days without some official inspection sticker saying I was okay. There were times when I dealt with the whole daily round—getting my child to kindergarten and the school, making two meals a day and serving them at set times, shopping, doing the garden, organizing children’s birthdays, appearing at club evenings, doing holidays, doing bookkeeping and finances, hairdresser’s appointments and obedience school for the dog, doing Easters and Christmases and on and on—I dealt with the whole thing as if it went without saying. And that wasn’t really the problem anyway.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Taut and absorbing. . . . This pulsing psychological portrait . . . is hard not to consume in one sitting.” –The New York Times Book Review

“Outstanding. . . . This cool first-person confessional . . . is a study in inner fragility and surface toughness.” –Ali Smith, The Times Literary Supplement

“Subtle. . . . Clear-eyed. . . . It is certainly a pleasure to read such a well-styled, level-headed novel. . . . It deserves success.” –The Guardian

“Riveting. Schmitter has reworked a great novel into a new and unique shape.” –The Boston Globe

“Outstanding. . . . This cool first-person confessional . . . is a study in inner fragility and surface toughness.” –Ali Smith, The Times Literary Supplement

“Subtle. . . . Clear-eyed. . . . It is certainly a pleasure to read such a well-styled, level-headed novel. . . . It deserves success.” –The Guardian

“Riveting. Schmitter has reworked a great novel into a new and unique shape.” –The Boston Globe