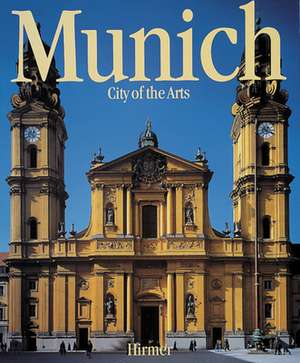

Munich: City of the Arts

Autor Hans F. Nohbauer Fotografii de Achim Bunzen Limba Engleză Hardback – 30 noi 1994

Breathtaking photographs and details provide a tour through the rich sites of this legendary city. Tracing Munich's history from the 12th century through the present, this sumptuous book illustrates the city's treasures, from the collections of antiquities in the Alte Pinakothek, to incomparable baroque and rococo buildings, to the neon-lit festivities of the modern-day Oktoberfest.

Preț: 638.44 lei

Preț vechi: 796.51 lei

-20% Nou

Puncte Express: 958

Preț estimativ în valută:

122.18€ • 126.78$ • 102.12£

122.18€ • 126.78$ • 102.12£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781558598652

ISBN-10: 1558598650

Pagini: 348

Dimensiuni: 267 x 324 x 47 mm

Greutate: 3.53 kg

Editura: Abbeville Publishing Group

Colecția Abbeville Press

ISBN-10: 1558598650

Pagini: 348

Dimensiuni: 267 x 324 x 47 mm

Greutate: 3.53 kg

Editura: Abbeville Publishing Group

Colecția Abbeville Press

Cuprins

CHRONICLE OF THE CITY

The Ducal Age

Henry the Lion, Founder of Munich

The Early Settlement

The Rise of the Wittelsbachs

Imperial Interlude: Ludwig the Bavarian

Power Struggles

Civic Construction: Frauenkirche and City Hall

The Capital of Bavaria

The Munich Renaissance Court

A Legendary Princely Wedding

Stronghold of the Counter-Reformation

Salt, Beer and Alchemy

The Age of Electors

Patrona Bavariae

The Italian Spirit

Max Emanuel, the “Blue Elector”

Views of the Baroque Town

Munich Rococo

Karl Theodor, the Elector from the Palatinate

The English Garden

The Age of Kings

Alliance with Napoleon

Munich Institutions: Oktoberfest and Nationaltheater

Ludwig I and Munich Classicism

Maximillian II: Neo-Gothic and the “Luminaries of the North”

Into the Industrial Age

The New City Hall

Munich Makes Musical History

Munich Painters

The Muse of Schwabing

Art Nouveau in Munich

“The Decline of the West”

The Republican Age

The End of the Monarchy

The March to the Feldherrnhalle

A German Museum for Technology

En Route to the Metropolitan Village

Harbingers of Fire

“Degenerate Art”

“Capital of the Nazi Movement”

The Secret Capital of Germany

VIEWS OF THE CITY

The Old City Centre

Town Models

The Princely City

The Residenz

Nymphenburg

Schleissheim

City of the Muses: Galleries and Museums

The Royal Collections: the Pinakotheks and the Glyptothek

Painter-Princes and “Der Blaue Reiter”

Royal City and State Capital

The Modern Metropolis

APPENDIX

Chronological Table of the History of Munich and Bavaria

Genealogical Table of the House of Wittelsbach in Bavaria

Plan of the City

Bibliography

Index

Photographic Acknowledgements

The Ducal Age

Henry the Lion, Founder of Munich

The Early Settlement

The Rise of the Wittelsbachs

Imperial Interlude: Ludwig the Bavarian

Power Struggles

Civic Construction: Frauenkirche and City Hall

The Capital of Bavaria

The Munich Renaissance Court

A Legendary Princely Wedding

Stronghold of the Counter-Reformation

Salt, Beer and Alchemy

The Age of Electors

Patrona Bavariae

The Italian Spirit

Max Emanuel, the “Blue Elector”

Views of the Baroque Town

Munich Rococo

Karl Theodor, the Elector from the Palatinate

The English Garden

The Age of Kings

Alliance with Napoleon

Munich Institutions: Oktoberfest and Nationaltheater

Ludwig I and Munich Classicism

Maximillian II: Neo-Gothic and the “Luminaries of the North”

Into the Industrial Age

The New City Hall

Munich Makes Musical History

Munich Painters

The Muse of Schwabing

Art Nouveau in Munich

“The Decline of the West”

The Republican Age

The End of the Monarchy

The March to the Feldherrnhalle

A German Museum for Technology

En Route to the Metropolitan Village

Harbingers of Fire

“Degenerate Art”

“Capital of the Nazi Movement”

The Secret Capital of Germany

VIEWS OF THE CITY

The Old City Centre

Town Models

The Princely City

The Residenz

Nymphenburg

Schleissheim

City of the Muses: Galleries and Museums

The Royal Collections: the Pinakotheks and the Glyptothek

Painter-Princes and “Der Blaue Reiter”

Royal City and State Capital

The Modern Metropolis

APPENDIX

Chronological Table of the History of Munich and Bavaria

Genealogical Table of the House of Wittelsbach in Bavaria

Plan of the City

Bibliography

Index

Photographic Acknowledgements

Notă biografică

Hans F. Nöhbauer is the author of various books on the history and culture of Bavaria, including the The Chronicle of Bavaria.

Dr. Nöhbauer is the arts editor of Abendzeitung, the prominent Munich daily. Achim Bunz was educated at the Academy for Photodesign in Munich. His photographs have been frequently published in leading European newspaper and magazines.

Dr. Nöhbauer is the arts editor of Abendzeitung, the prominent Munich daily. Achim Bunz was educated at the Academy for Photodesign in Munich. His photographs have been frequently published in leading European newspaper and magazines.

Extras

THE DUCAL AGE

Henry the Lion, Founder of Munich

Two high-ranking princes, Bishop Otto of Freising and Duke Henry XII of Bavaria, disputed each other’s rights to the route by which the salt from Reichenhall was to cross the River Isar. The dispute was decided by an even higher authority in Augsburg on 14 June 1158 – by the Hohenstaufen Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa. He put his seal on a 15-line Latin document, one of many drawn up in the chancellery, that settled the awkward affair once and for all. In this imperial document, which has been preserved to the present day, the name “Munichen” is mentioned for the first time.

More explicitly than in this first brief imperial report the factual account of the founding of Munich is recorded in the Barbarossa charter 22 years later: Henry had attacked and destroyed the bridge and market at Fohring, which belonged to the See of Freising, and had had them rebuilt a few miles upstream on his own territory.

Mediating a settlement satisfactory to both princes was a delicate task for Barbarossa, who in his charter addresses Bishop Otto of Freising of the House of Babenberg as his “beloved Uncle”, and the Duke of Bavaria, the Guelph Henry the Lion, as his “esteemed Cousin”. In order not to insult either of his powerful kinsmen, the Hohenstaufen ruler made the following judgement: in future, market, customs bridge and mint were to be located in Munich. In return, Duke Henry had to make restitution and pay a third of the revenues to the Bishop of Freising (and until secularization in 1803 this was duly remitted).

The emperor, sanctioning the duke’s breach of the law rather than punishing him for it, was probably not only making concessions to the belligerent parties, but had his own interests in mind. Henry the Lion, Duke of Saxony, and Duke of Bavaria since 1156, was a powerful German prince on whose support Barbarossa relied in his difficult political negotiations concerning Italy. For reasons of pure expediency he let the duke keep what he had already seized by force from the Bishop of Freising.

On the other hand, prudence dictated that the emperor should prevent his cousin from becoming too powerful. Both the Hohenstaufen and the Guelphs boasted landholdings in the south-west of Germany. By granting the Bishop of Freising a share in the market and customs revenues, Henry’s influence could be curtailed, and any danger to the imperial and Hohenstaufen lands between the River Lech and Lake Constance would be diminished. That is how the arbitration away of Augsburg came about, finely balancing out the interests of the three leading princely houses: the Hohenstaufen, Guelphs, and Babenbergs. In the end, however, Duke Henry’s coup at Fohring proved of little effect, because after refusing to support imperial policies in Italy, he was forced into exile in 1180 and deprived of his two duchies. Bavaria, which had been held by the Guelphs since 1070 (with a brief Babenberg interregnum from 1139 to 1156), was now given to the Count Palatine Otto of Wittelsbach.

One now recalled (after more than 20 years) that the violation of Bishop Otto’s rights at Fohring in 1158 had been settled by a not entirely honest compromise. The award was officially revoked and Munich committed to destruction. No contemporary reports record that this verdict was actually carried out, however, except for a monk’s brief entry in the almanac of the monastery of Schaftlarn in 1180: “Munich was razed, Vehringen rebuilt.” Obviously the pious man mistook intention for action.

The Early Settlement

The origins of the small settlement “home of the monks” (bei den Monchen) can be traced back to a time long before 1158, the year of the official founding of Munich. The monk in the city’s coat of arms recalls these monastic origins, as does St Peter’s Church, which was later built on the site of a small chapel that had stood there at a much earlier date. But it was only after the “Augsburg Award” (Augsburger Schied) that Munich grew and became a flourishing trading centre. And although on that Whit Sunday in the year 1158 the emperor had merely issued a kind of trading license – by no means a certificate of birth or baptism – 14 June os still observed as the anniversary of Munich’s birth. Even today city maps clearly show the outlines of the early, so-called Heinrichsstadt, the oval core of old Munich, which over the past 850 years has grown to almost 2,000 times its original size.

The first settlers were circumspect people who made the best of the vagaries of the River Isar by building their homes high up the embankment out of reach of this mountain stream, which at the time was still fed by many smaller tributaries. It was here that early settlers waited for the salt loads and collected customs dues from traders before their wagons rumbled on. Apart from salt in those early centuries, the merchants of Munich also traded in wine and cloth, although they had hardly any share in what was considered international trade in those days. All the important European trade routes passed at a great distance from Munich. The most important centres were Augsburg and Nuremberg.

The duke’s perusal of the revenue books, which showed the yield of taxes he received from the citizens of Munich, must have made pleasant reading; but otherwise he showed no great interest in this Bavarian settlement, in which he probably never set foot. He preferred to roam his Dukedom of Saxony and, although his forebears originally came from the area of Metz and had risen to fame in south Germany, he was far more interested in the development of the north-eastern provinces of Germany. It was therefore a fortunate turn of events for the citizens of Munich, when, in 1180, the emperor deprived his cousin of all his fiefs and rewarded his true vassal, Otto of Wittelsbach, with the Dukedom of Bavaria.

Henry the Lion, Founder of Munich

Two high-ranking princes, Bishop Otto of Freising and Duke Henry XII of Bavaria, disputed each other’s rights to the route by which the salt from Reichenhall was to cross the River Isar. The dispute was decided by an even higher authority in Augsburg on 14 June 1158 – by the Hohenstaufen Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa. He put his seal on a 15-line Latin document, one of many drawn up in the chancellery, that settled the awkward affair once and for all. In this imperial document, which has been preserved to the present day, the name “Munichen” is mentioned for the first time.

More explicitly than in this first brief imperial report the factual account of the founding of Munich is recorded in the Barbarossa charter 22 years later: Henry had attacked and destroyed the bridge and market at Fohring, which belonged to the See of Freising, and had had them rebuilt a few miles upstream on his own territory.

Mediating a settlement satisfactory to both princes was a delicate task for Barbarossa, who in his charter addresses Bishop Otto of Freising of the House of Babenberg as his “beloved Uncle”, and the Duke of Bavaria, the Guelph Henry the Lion, as his “esteemed Cousin”. In order not to insult either of his powerful kinsmen, the Hohenstaufen ruler made the following judgement: in future, market, customs bridge and mint were to be located in Munich. In return, Duke Henry had to make restitution and pay a third of the revenues to the Bishop of Freising (and until secularization in 1803 this was duly remitted).

The emperor, sanctioning the duke’s breach of the law rather than punishing him for it, was probably not only making concessions to the belligerent parties, but had his own interests in mind. Henry the Lion, Duke of Saxony, and Duke of Bavaria since 1156, was a powerful German prince on whose support Barbarossa relied in his difficult political negotiations concerning Italy. For reasons of pure expediency he let the duke keep what he had already seized by force from the Bishop of Freising.

On the other hand, prudence dictated that the emperor should prevent his cousin from becoming too powerful. Both the Hohenstaufen and the Guelphs boasted landholdings in the south-west of Germany. By granting the Bishop of Freising a share in the market and customs revenues, Henry’s influence could be curtailed, and any danger to the imperial and Hohenstaufen lands between the River Lech and Lake Constance would be diminished. That is how the arbitration away of Augsburg came about, finely balancing out the interests of the three leading princely houses: the Hohenstaufen, Guelphs, and Babenbergs. In the end, however, Duke Henry’s coup at Fohring proved of little effect, because after refusing to support imperial policies in Italy, he was forced into exile in 1180 and deprived of his two duchies. Bavaria, which had been held by the Guelphs since 1070 (with a brief Babenberg interregnum from 1139 to 1156), was now given to the Count Palatine Otto of Wittelsbach.

One now recalled (after more than 20 years) that the violation of Bishop Otto’s rights at Fohring in 1158 had been settled by a not entirely honest compromise. The award was officially revoked and Munich committed to destruction. No contemporary reports record that this verdict was actually carried out, however, except for a monk’s brief entry in the almanac of the monastery of Schaftlarn in 1180: “Munich was razed, Vehringen rebuilt.” Obviously the pious man mistook intention for action.

The Early Settlement

The origins of the small settlement “home of the monks” (bei den Monchen) can be traced back to a time long before 1158, the year of the official founding of Munich. The monk in the city’s coat of arms recalls these monastic origins, as does St Peter’s Church, which was later built on the site of a small chapel that had stood there at a much earlier date. But it was only after the “Augsburg Award” (Augsburger Schied) that Munich grew and became a flourishing trading centre. And although on that Whit Sunday in the year 1158 the emperor had merely issued a kind of trading license – by no means a certificate of birth or baptism – 14 June os still observed as the anniversary of Munich’s birth. Even today city maps clearly show the outlines of the early, so-called Heinrichsstadt, the oval core of old Munich, which over the past 850 years has grown to almost 2,000 times its original size.

The first settlers were circumspect people who made the best of the vagaries of the River Isar by building their homes high up the embankment out of reach of this mountain stream, which at the time was still fed by many smaller tributaries. It was here that early settlers waited for the salt loads and collected customs dues from traders before their wagons rumbled on. Apart from salt in those early centuries, the merchants of Munich also traded in wine and cloth, although they had hardly any share in what was considered international trade in those days. All the important European trade routes passed at a great distance from Munich. The most important centres were Augsburg and Nuremberg.

The duke’s perusal of the revenue books, which showed the yield of taxes he received from the citizens of Munich, must have made pleasant reading; but otherwise he showed no great interest in this Bavarian settlement, in which he probably never set foot. He preferred to roam his Dukedom of Saxony and, although his forebears originally came from the area of Metz and had risen to fame in south Germany, he was far more interested in the development of the north-eastern provinces of Germany. It was therefore a fortunate turn of events for the citizens of Munich, when, in 1180, the emperor deprived his cousin of all his fiefs and rewarded his true vassal, Otto of Wittelsbach, with the Dukedom of Bavaria.