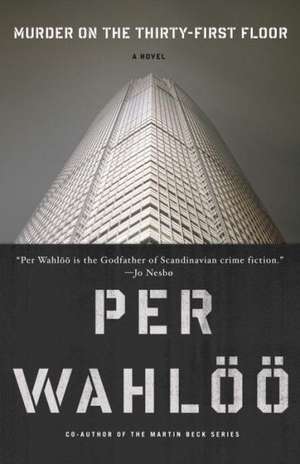

Murder on the the Thirty-First Floor

Autor Per Wahloo Traducere de Sarah Deathen Limba Engleză Paperback – 25 feb 2013

Jensen has never had a case he could not solve before, but as his investigation into the identity of the letter writer begins it soon becomes clear that the directors of the publishers have their own secrets, not least the identity of the 'Special Department' on the thirty first floor; the only department not permitted to be evacuated after the bomb threat.

Preț: 76.72 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 115

Preț estimativ în valută:

14.68€ • 15.96$ • 12.34£

14.68€ • 15.96$ • 12.34£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307744456

ISBN-10: 0307744450

Pagini: 215

Dimensiuni: 129 x 208 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: VINTAGE BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0307744450

Pagini: 215

Dimensiuni: 129 x 208 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: VINTAGE BOOKS

Extras

Chapter 1

The alarm was raised at exactly 13.02. The chief of police phoned the order through personally to the Sixteenth police District and ninety seconds later the alarm bell sounded in the oper-ational rooms and administrative offices on the ground floor. It was still ringing when Inspector Jensen got down from his room. Jensen was a middle-aged police officer of normal build, with an unlined and expressionless face. On the bottom step of the spiral staircase he stopped and let his eyes scan the reception area. He adjusted his tie and went out to his car.

The midday traffic was heavy, a mass of gleaming sheet metal, and the buildings of the city, a maze of glass and concrete pillars, rose from the stream of cars. In this world of hard surfaces, the people on the pavements looked homeless and dissatisfied. They were well dressed but strangely identical, and all of them were in a hurry. They swarmed on their way in jerky queues, clotting at red lights and fast-food outlets of shiny chrome. They looked constantly about them and fiddled with their briefcases and handbags.

Sirens wailing, the police cars bored through the crush.

Inspector Jensen was travelling in the first vehicle, a dark blue, standard-issue, PVC-panelled police car; it was followed by a van with grey bodywork, bars at the windows of the rear doors and a flashing light on the roof.

The police chief came through via the radio control room.

‘Jensen?’

‘Yes?’

‘Where are you?’

‘In front of the Trades Union Palace . . .’

‘Have you got the sirens on?’

‘Yes.’

‘Turn them off as soon as you’re through the square.’

‘The traffic’s really bad.’

‘It can’t be helped. You’ve got to avoid attracting attention.’

‘The reporters are tuned in to us all the time, anyway.’

‘You needn’t worry about them. I’m thinking about the public. The man in the street.’

‘Understood.’

‘Are you in uniform?’

‘No.’

‘Good. What manpower have you got with you?’

‘One, plus four from the plainclothes patrol. And then the police van, with an additional nine constables. In uniform.’

‘Only those in plain clothes are to show themselves inside or in the immediate vicinity of the building. Have the van set down half the men three hundred metres before you get there. Then it can drive straight past and park higher up, at a safe distance.’

‘Understood.’

‘Close off the main street and the side roads leading into it.’

‘Understood.’

‘If anyone asks, the closure’s for emergency roadworks. Something like . . .’

He tailed off.

‘A burst pipe in the district heating system?’

‘Spot on.’

There was a crackle on the line.

‘Jensen?’

‘Yes.’

‘You’ll remember about the titles business?’

‘The titles business?’

‘I thought everybody knew. You mustn’t refer to any of them as Director.’

‘Understood.’

‘They’re very sensitive on that point.’

‘I see.’

‘I’m sure I don’t need to re-emphasise the delicate nature of the operation?’

‘No.’

A mechanical rushing sound. Something that could have been a sigh, deep and metallic.

‘Where are you now?’

‘The south side of the square. In front of the workers’ monument.’

‘Turn off the sirens.’

‘Done.’

‘Space the vehicles out more.’

‘Done.’

‘I’m sending all available radio patrol cars as backup. They’ll come up to the parking area. Hold them in reserve.’

‘Understood.’

‘Where are you?’

‘The highway on the north side of the square. I can see the building.’

The road was broad and straight, with six lanes and a narrow, white-painted traffic island along the middle. Behind a tall, wire-mesh fence running along the western side there was an embankment, and at the bottom a vast long-distance lorry depot with hundreds of warehouses and white and red trucks queuing at the loading platforms. A number of people were moving about down there, mainly packers and drivers in white boiler suits and red caps.

The road ran uphill, cutting through a ridge of solid rock that had been blasted away. Its eastern side was a wall of granite, its irregularities smoothed over with concrete. It was pale blue, with rusty vertical stripes caused by the reinforcement bars, and just visible above it were the tops of a few leafless trees. From down below you couldn’t see the buildings beyond the trees, but Jensen knew they were there, and what they looked like. One of them was a mental hospital.

At its highest point, the road came level with the top of the ridge and curved slightly to the right. And that was where the Skyscraper stood; it was one of the tallest buildings in the country, its elevated position making it visible from all over the city. You could always see it there above you, and whatever direction you were coming from, it seemed to be the point towards which your approach road was leading.

The Skyscraper had a square layout and thirty floors. Each of its façades had four hundred and fifty windows and a white clock with red hands. Its exterior was of glass, the panels dark blue at ground level, fading gradually to lighter shades on the higher floors.

To Jensen, peering through the windscreen, the Skyscraper seemed to shoot up out of the ground and grow into the cold, cloudless spring sky.

Still with the radio telephone pressed to his ear, he leaned forward. The Skyscraper enlarged to fill his entire field of vision.

‘Jensen?’

‘Yes.’

‘I’m relying on you. It’s your job now to make an assessment of the situation.’

There was a brief, crackling pause. Then the police chief gave a hesitant:

‘Over and out.’

Chapter 2

The rooms on the eighteenth floor were carpeted in pale blue. There were two large model ships in display cases and a reception area with easy chairs and kidney-shaped tables.

In a room with glass walls sat three unoccupied young women. One of them glanced in the visitor’s direction and said:

‘Can I help you?’

‘My name’s Jensen. It’s urgent.’

‘Oh?’

She rose lazily, crossed the floor with light, practised nonchalance and opened a door: ‘There’s someone called Jensen here.’

Her legs were shapely and her waist slim. Her clothes displayed no taste.

Another woman appeared in the doorway. She looked a little older, though not much, and had blonde hair, distinct features and a generally antiseptic appearance.

She looked past her assistant and said:

‘Come in. You’re expected.’

The corner room had six windows and the city lay spread below them, as unreal and lifeless as a model on a topographical map. In spite of the dazzling sun, the view and visibility were superb, the daylight clear and cold. The colours in the room were clean and hard and the walls very light, as were the floor covering and the tubular steel furniture.

There was a glass-fronted cabinet between the windows, containing silver coloured cups, engraved with wreaths of oak leaves and borne aloft by bases of black wood. Most of the cups were crowned with naked archers or eagles with outspread wings.

On the desk stood an intercom, a very large stainless steel ashtray and an ivory coloured cobra.

On top of the glass-fronted cabinet was a red-and-white flag on a chrome stand, designed for tabletop use, and under the desk there were a pair of pale yellow sandals and an empty aluminium waste-paper bin.

In the middle of the desk lay a letter, marked special delivery.

There were two men in the room.

One of them was standing at one end of the desk, his fingertips resting on the polished surface. He was wearing a well-pressed dark suit, hand-stitched black shoes, a white shirt and a silver-grey silk tie. His face was smooth and servile, his hair neatly combed and his eyes almost canine behind thick, horn-rimmed glasses. Jensen had often seen faces like that, particularly on television.

The other man, who looked somewhat younger, was wearing yellow-and-white-striped socks, light brown trousers and a loose white shirt, unbuttoned at the neck. He was kneeling on a chair over by one of the windows with his chin in his hand and his elbows resting on the white marble sill. He was blond and blue-eyed and had no shoes on.

Jensen showed his ID and took a step towards the desk.

‘Are you in charge here, sir?

The man in the silk tie shook his head deprecatingly and backed away from the desk with slight bowing movements and vague but eager gestures towards the window. His smile defied analysis.

The blond man slid from the chair and came padding across the floor. He gave Jensen a short, hearty shake of the hand. Then he indicated the desk.

‘There,’ he said.

The envelope was white, and very ordinary. It had three stamps on it and, in the bottom left hand corner, the red special delivery sticker. Inside the envelope was a sheet of paper, folded in four. Both the address and the message itself were composed of individual letters of the alphabet, obviously cut out of a newspaper or magazine. The paper seemed to be of extremely good quality and the size looked rather unusual. Jensen held the sheet between the tips of his fingers and read:

as a reprisal for the murder committed by you a powerful explosive charge has been placed on the premises it has a timer and is set to detonate at exactly fourteen hundred hours on the twenty-third of March let those who are innocent save themselves

‘She’s mad, of course,’ said the blond-haired man. ‘Mentally ill, that’s all there is to it.’

‘Yes, that’s the conclusion we’ve reached,’ said the man in the silk tie.

‘Either that or it’s a very bad joke,’ said the blond man.

‘And in unusually poor taste.’

‘Well yes, that could be the case, of course,’ said the man in the silk tie.

The blond-haired man gave him an apathetic look. Then he said, ‘This is one of our directors. Head of publishing . . .’ He hesitated momentarily and then added, ‘My right-hand man.’

The other man’s smile widened and he inclined his head. It might have been a greeting, or perhaps he was lowering his head for some other reason. Shame, for example, or deference, or pride.

‘We have ninety-eight other directors,’ said the blond man.

Inspector Jensen looked at his watch. It showed 13.19.

‘I thought I heard you say “she”, Director. Do you have reason to suspect the sender is a woman?’

‘I’m usually referred to simply as publisher,’ said the blond man.

He ambled round the desk, sat down and put his right leg over the arm of the chair.

‘No,’ he said, ‘Of course not. I must have just happened to phrase it that way. Someone must have put together that letter.’

‘Just so,’ said the head of publishing.

‘I wonder who?’ said the blond man.

‘Yes,’ said the head of publishing.

His smile had vanished and been replaced by a deep, pensive frown.

The publisher swung his left leg, too, over the arm of his chair.

Jensen looked at his watch again. 13.21.

‘The premises must be evacuated,’ he said.

‘Evacuated? That won’t be possible. It would mean stopping the whole production line. Maybe for several hours. Do you have any idea what that would cost?’

He spun the revolving chair round with a kick and fixed his right-hand man with a challenging look. The head of publishing instantly furrowed his brow still further and started a mumbled calculation on his fingers. The man who wanted to be referred to as a publisher regarded him coldly and swung himself back.

‘At least three-quarters of a million,’ he said. ‘Have you got that? Three-quarters of a million. At least. Maybe twice that.’

Jensen read the letter through again. Looked at his watch. 13.23.

The publisher went on:

‘We publish one hundred and forty-four magazines. They’re all produced in this building. Their joint print run comes to more than twenty-one million copies. A week. There’s nothing more important than getting them printed and distributed on time.’

His face changed. The blue eyes seemed to grow clearer.

‘In every home in the land, people are waiting for their magazines. It’s the same for everyone, from princesses at court to farmers’ wives, from the top men and women in society to the down-and-outs, if there are any; it applies to them all.’

He paused briefly. Then went on. ‘And the little children. All the little children.’

‘The little children?’

‘Yes, ninety-eight of our magazines are for children, for the little ones.’

‘Comics,’ clarified the head of publishing.

The blond man gave him an ungrateful look, and his face changed again. He kicked his chair round irritably and glared at Jensen.

‘Well, Inspector?’

‘With all due respect for what you’ve just told me, I still think the premises should be evacuated,’ Jensen said.

‘Is that all you’ve got to say? What are your people doing, by the way?’

‘Searching.’

‘If there’s a bomb, then presumably they’ll find it?’

‘They’re extremely competent, but they’ve very little time at their disposal. An explosive charge can be very difficult to locate. It could be hidden practically anywhere. The instant my men find anything they will report directly to me here.’

‘They’ve still got three-quarters of an hour.’

Jensen looked at his watch.

‘Thirty-five minutes. But even if the charge is found, disarming it can take some time.’

‘And if there isn’t a bomb?’

‘I must still advise evacuation.’

‘Even if the risk is assessed as small?’

‘Yes. It may be that the threat won’t be carried out, that nothing will happen. But there are unfortunately instances where the opposite has occurred.’

‘Where?’

‘In the history of crime.’

Jensen clasped his hands behind his back and rocked on the balls of his feet.

‘That’s my professional assessment, anyway,’ he said.

The publisher gave him a long look.

‘How much would it cost us for your assessment to turn out to be a different one?’ he said.

Jensen regarded him stonily.

The man at the desk appeared to resign himself.

‘Only joking, of course,’ he said grimly.

He put his feet down, turned the chair to face the right way, rested his arms on the desktop in front of him and crumpled forward, his forehead slumping on to his clenched left hand. He pulled himself upright with a jerk.

‘We’ll have to confer with my cousin,’ he said, pressing a button on the intercom.

Jensen checked the time. 13.27.

The alarm was raised at exactly 13.02. The chief of police phoned the order through personally to the Sixteenth police District and ninety seconds later the alarm bell sounded in the oper-ational rooms and administrative offices on the ground floor. It was still ringing when Inspector Jensen got down from his room. Jensen was a middle-aged police officer of normal build, with an unlined and expressionless face. On the bottom step of the spiral staircase he stopped and let his eyes scan the reception area. He adjusted his tie and went out to his car.

The midday traffic was heavy, a mass of gleaming sheet metal, and the buildings of the city, a maze of glass and concrete pillars, rose from the stream of cars. In this world of hard surfaces, the people on the pavements looked homeless and dissatisfied. They were well dressed but strangely identical, and all of them were in a hurry. They swarmed on their way in jerky queues, clotting at red lights and fast-food outlets of shiny chrome. They looked constantly about them and fiddled with their briefcases and handbags.

Sirens wailing, the police cars bored through the crush.

Inspector Jensen was travelling in the first vehicle, a dark blue, standard-issue, PVC-panelled police car; it was followed by a van with grey bodywork, bars at the windows of the rear doors and a flashing light on the roof.

The police chief came through via the radio control room.

‘Jensen?’

‘Yes?’

‘Where are you?’

‘In front of the Trades Union Palace . . .’

‘Have you got the sirens on?’

‘Yes.’

‘Turn them off as soon as you’re through the square.’

‘The traffic’s really bad.’

‘It can’t be helped. You’ve got to avoid attracting attention.’

‘The reporters are tuned in to us all the time, anyway.’

‘You needn’t worry about them. I’m thinking about the public. The man in the street.’

‘Understood.’

‘Are you in uniform?’

‘No.’

‘Good. What manpower have you got with you?’

‘One, plus four from the plainclothes patrol. And then the police van, with an additional nine constables. In uniform.’

‘Only those in plain clothes are to show themselves inside or in the immediate vicinity of the building. Have the van set down half the men three hundred metres before you get there. Then it can drive straight past and park higher up, at a safe distance.’

‘Understood.’

‘Close off the main street and the side roads leading into it.’

‘Understood.’

‘If anyone asks, the closure’s for emergency roadworks. Something like . . .’

He tailed off.

‘A burst pipe in the district heating system?’

‘Spot on.’

There was a crackle on the line.

‘Jensen?’

‘Yes.’

‘You’ll remember about the titles business?’

‘The titles business?’

‘I thought everybody knew. You mustn’t refer to any of them as Director.’

‘Understood.’

‘They’re very sensitive on that point.’

‘I see.’

‘I’m sure I don’t need to re-emphasise the delicate nature of the operation?’

‘No.’

A mechanical rushing sound. Something that could have been a sigh, deep and metallic.

‘Where are you now?’

‘The south side of the square. In front of the workers’ monument.’

‘Turn off the sirens.’

‘Done.’

‘Space the vehicles out more.’

‘Done.’

‘I’m sending all available radio patrol cars as backup. They’ll come up to the parking area. Hold them in reserve.’

‘Understood.’

‘Where are you?’

‘The highway on the north side of the square. I can see the building.’

The road was broad and straight, with six lanes and a narrow, white-painted traffic island along the middle. Behind a tall, wire-mesh fence running along the western side there was an embankment, and at the bottom a vast long-distance lorry depot with hundreds of warehouses and white and red trucks queuing at the loading platforms. A number of people were moving about down there, mainly packers and drivers in white boiler suits and red caps.

The road ran uphill, cutting through a ridge of solid rock that had been blasted away. Its eastern side was a wall of granite, its irregularities smoothed over with concrete. It was pale blue, with rusty vertical stripes caused by the reinforcement bars, and just visible above it were the tops of a few leafless trees. From down below you couldn’t see the buildings beyond the trees, but Jensen knew they were there, and what they looked like. One of them was a mental hospital.

At its highest point, the road came level with the top of the ridge and curved slightly to the right. And that was where the Skyscraper stood; it was one of the tallest buildings in the country, its elevated position making it visible from all over the city. You could always see it there above you, and whatever direction you were coming from, it seemed to be the point towards which your approach road was leading.

The Skyscraper had a square layout and thirty floors. Each of its façades had four hundred and fifty windows and a white clock with red hands. Its exterior was of glass, the panels dark blue at ground level, fading gradually to lighter shades on the higher floors.

To Jensen, peering through the windscreen, the Skyscraper seemed to shoot up out of the ground and grow into the cold, cloudless spring sky.

Still with the radio telephone pressed to his ear, he leaned forward. The Skyscraper enlarged to fill his entire field of vision.

‘Jensen?’

‘Yes.’

‘I’m relying on you. It’s your job now to make an assessment of the situation.’

There was a brief, crackling pause. Then the police chief gave a hesitant:

‘Over and out.’

Chapter 2

The rooms on the eighteenth floor were carpeted in pale blue. There were two large model ships in display cases and a reception area with easy chairs and kidney-shaped tables.

In a room with glass walls sat three unoccupied young women. One of them glanced in the visitor’s direction and said:

‘Can I help you?’

‘My name’s Jensen. It’s urgent.’

‘Oh?’

She rose lazily, crossed the floor with light, practised nonchalance and opened a door: ‘There’s someone called Jensen here.’

Her legs were shapely and her waist slim. Her clothes displayed no taste.

Another woman appeared in the doorway. She looked a little older, though not much, and had blonde hair, distinct features and a generally antiseptic appearance.

She looked past her assistant and said:

‘Come in. You’re expected.’

The corner room had six windows and the city lay spread below them, as unreal and lifeless as a model on a topographical map. In spite of the dazzling sun, the view and visibility were superb, the daylight clear and cold. The colours in the room were clean and hard and the walls very light, as were the floor covering and the tubular steel furniture.

There was a glass-fronted cabinet between the windows, containing silver coloured cups, engraved with wreaths of oak leaves and borne aloft by bases of black wood. Most of the cups were crowned with naked archers or eagles with outspread wings.

On the desk stood an intercom, a very large stainless steel ashtray and an ivory coloured cobra.

On top of the glass-fronted cabinet was a red-and-white flag on a chrome stand, designed for tabletop use, and under the desk there were a pair of pale yellow sandals and an empty aluminium waste-paper bin.

In the middle of the desk lay a letter, marked special delivery.

There were two men in the room.

One of them was standing at one end of the desk, his fingertips resting on the polished surface. He was wearing a well-pressed dark suit, hand-stitched black shoes, a white shirt and a silver-grey silk tie. His face was smooth and servile, his hair neatly combed and his eyes almost canine behind thick, horn-rimmed glasses. Jensen had often seen faces like that, particularly on television.

The other man, who looked somewhat younger, was wearing yellow-and-white-striped socks, light brown trousers and a loose white shirt, unbuttoned at the neck. He was kneeling on a chair over by one of the windows with his chin in his hand and his elbows resting on the white marble sill. He was blond and blue-eyed and had no shoes on.

Jensen showed his ID and took a step towards the desk.

‘Are you in charge here, sir?

The man in the silk tie shook his head deprecatingly and backed away from the desk with slight bowing movements and vague but eager gestures towards the window. His smile defied analysis.

The blond man slid from the chair and came padding across the floor. He gave Jensen a short, hearty shake of the hand. Then he indicated the desk.

‘There,’ he said.

The envelope was white, and very ordinary. It had three stamps on it and, in the bottom left hand corner, the red special delivery sticker. Inside the envelope was a sheet of paper, folded in four. Both the address and the message itself were composed of individual letters of the alphabet, obviously cut out of a newspaper or magazine. The paper seemed to be of extremely good quality and the size looked rather unusual. Jensen held the sheet between the tips of his fingers and read:

as a reprisal for the murder committed by you a powerful explosive charge has been placed on the premises it has a timer and is set to detonate at exactly fourteen hundred hours on the twenty-third of March let those who are innocent save themselves

‘She’s mad, of course,’ said the blond-haired man. ‘Mentally ill, that’s all there is to it.’

‘Yes, that’s the conclusion we’ve reached,’ said the man in the silk tie.

‘Either that or it’s a very bad joke,’ said the blond man.

‘And in unusually poor taste.’

‘Well yes, that could be the case, of course,’ said the man in the silk tie.

The blond-haired man gave him an apathetic look. Then he said, ‘This is one of our directors. Head of publishing . . .’ He hesitated momentarily and then added, ‘My right-hand man.’

The other man’s smile widened and he inclined his head. It might have been a greeting, or perhaps he was lowering his head for some other reason. Shame, for example, or deference, or pride.

‘We have ninety-eight other directors,’ said the blond man.

Inspector Jensen looked at his watch. It showed 13.19.

‘I thought I heard you say “she”, Director. Do you have reason to suspect the sender is a woman?’

‘I’m usually referred to simply as publisher,’ said the blond man.

He ambled round the desk, sat down and put his right leg over the arm of the chair.

‘No,’ he said, ‘Of course not. I must have just happened to phrase it that way. Someone must have put together that letter.’

‘Just so,’ said the head of publishing.

‘I wonder who?’ said the blond man.

‘Yes,’ said the head of publishing.

His smile had vanished and been replaced by a deep, pensive frown.

The publisher swung his left leg, too, over the arm of his chair.

Jensen looked at his watch again. 13.21.

‘The premises must be evacuated,’ he said.

‘Evacuated? That won’t be possible. It would mean stopping the whole production line. Maybe for several hours. Do you have any idea what that would cost?’

He spun the revolving chair round with a kick and fixed his right-hand man with a challenging look. The head of publishing instantly furrowed his brow still further and started a mumbled calculation on his fingers. The man who wanted to be referred to as a publisher regarded him coldly and swung himself back.

‘At least three-quarters of a million,’ he said. ‘Have you got that? Three-quarters of a million. At least. Maybe twice that.’

Jensen read the letter through again. Looked at his watch. 13.23.

The publisher went on:

‘We publish one hundred and forty-four magazines. They’re all produced in this building. Their joint print run comes to more than twenty-one million copies. A week. There’s nothing more important than getting them printed and distributed on time.’

His face changed. The blue eyes seemed to grow clearer.

‘In every home in the land, people are waiting for their magazines. It’s the same for everyone, from princesses at court to farmers’ wives, from the top men and women in society to the down-and-outs, if there are any; it applies to them all.’

He paused briefly. Then went on. ‘And the little children. All the little children.’

‘The little children?’

‘Yes, ninety-eight of our magazines are for children, for the little ones.’

‘Comics,’ clarified the head of publishing.

The blond man gave him an ungrateful look, and his face changed again. He kicked his chair round irritably and glared at Jensen.

‘Well, Inspector?’

‘With all due respect for what you’ve just told me, I still think the premises should be evacuated,’ Jensen said.

‘Is that all you’ve got to say? What are your people doing, by the way?’

‘Searching.’

‘If there’s a bomb, then presumably they’ll find it?’

‘They’re extremely competent, but they’ve very little time at their disposal. An explosive charge can be very difficult to locate. It could be hidden practically anywhere. The instant my men find anything they will report directly to me here.’

‘They’ve still got three-quarters of an hour.’

Jensen looked at his watch.

‘Thirty-five minutes. But even if the charge is found, disarming it can take some time.’

‘And if there isn’t a bomb?’

‘I must still advise evacuation.’

‘Even if the risk is assessed as small?’

‘Yes. It may be that the threat won’t be carried out, that nothing will happen. But there are unfortunately instances where the opposite has occurred.’

‘Where?’

‘In the history of crime.’

Jensen clasped his hands behind his back and rocked on the balls of his feet.

‘That’s my professional assessment, anyway,’ he said.

The publisher gave him a long look.

‘How much would it cost us for your assessment to turn out to be a different one?’ he said.

Jensen regarded him stonily.

The man at the desk appeared to resign himself.

‘Only joking, of course,’ he said grimly.

He put his feet down, turned the chair to face the right way, rested his arms on the desktop in front of him and crumpled forward, his forehead slumping on to his clenched left hand. He pulled himself upright with a jerk.

‘We’ll have to confer with my cousin,’ he said, pressing a button on the intercom.

Jensen checked the time. 13.27.

Notă biografică

Born in 1926, Per Wahlöö was a Swedish writer and journalist who, alongside his own novels, collaborated with his wife, Maj Sjöwall, on the bestselling Martin Beck crime series which are credited as inspiring writers as varied as Agatha Christie, Henning Mankell and Jonathan Franzen. In 1971 the fourth novel in the series, The Laughing Policeman, won an Edgar Award from the Mystery Writers of America. Per Wahlöö died in 1975.