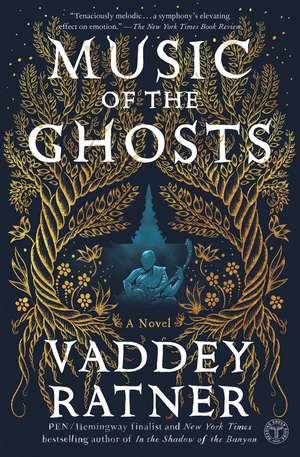

Music of the Ghosts: A Novel

Autor Vaddey Ratneren Limba Engleză Paperback – 14 iun 2018

Leaving the safety of America, Teera returns to Cambodia for the first time since her harrowing escape as a child refugee. She carries a letter from a man who mysteriously signs himself as “the Old Musician” and claims to have known her father in the Khmer Rouge prison where he disappeared twenty-five years ago.

In Phnom Penh, Teera finds a society still in turmoil, where perpetrators and survivors of unfathomable violence live side by side, striving to mend their still beloved country. She meets a young doctor who begins to open her heart, confronts her long-buried memories, and prepares to learn her father’s fate.

Meanwhile, the Old Musician, who earns his modest keep playing ceremonial music at a temple, awaits Teera’s visit. He will have to confess the bonds he shared with her parents, the passion with which they all embraced the Khmer Rouge’s illusory promise of a democratic society, and the truth about her father’s end.

A love story for things lost and restored, a lyrical hymn to the power of forgiveness, Music of the Ghosts is a “sensitive portrait of the inheritance of survival” (USA TODAY) and a journey through the embattled geography of the heart where love can be reborn.

Preț: 125.72 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 189

Preț estimativ în valută:

24.06€ • 26.15$ • 20.23£

24.06€ • 26.15$ • 20.23£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 31 martie-14 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781476795799

ISBN-10: 1476795797

Pagini: 352

Dimensiuni: 140 x 210 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Editura: ATRIA

Colecția Atria Books

ISBN-10: 1476795797

Pagini: 352

Dimensiuni: 140 x 210 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Editura: ATRIA

Colecția Atria Books

Notă biografică

Vaddey Ratner is a survivor of the Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia. Her critically acclaimed bestselling debut novel, In the Shadow of the Banyan, was a Finalist for the PEN/Hemingway Award and has been translated into seventeen languages. She is a summa cum laude graduate of Cornell University, where she specialized in Southeast Asian history and literature. Her most recent novel is Music of the Ghosts.

Extras

Music of the Ghosts

He feels his way in the confined space of the wooden cottage, hands groping in the dark, searching among the shadows through the blurred vision of his one good eye for the sadiev. The lute has called out to him in his dream, plucking its way persistently into his consciousness, until he’s awake, aware of its presence beside him. His fingers find the instrument. It lies aslant on the bamboo bed, deeply reposed in its dreamlessness. His fingers inadvertently brush against the single copper string, coaxing a soft ktock, similar to the click of a baby’s tongue. The Old Musician is almost blind, his left eye damaged long ago by a bludgeon and his right by age. He relies much on his senses to see, and now he sees her, feels her presence, not as a ghostly apparition overwhelming the tiny space of his cottage, nor as a thought occupying his mind, but as a longing on the verge of utterance, incarnation. He feels her move toward him. She who will inherit the sadiev, this ancient instrument used to invoke the spirits of the dead, as if in that solitary note, he has called her to him.

He lifts the lute to his chest, rousing it from its muted sleep, holding it as he often held his small daughter a lifetime ago, her heart against his heart, her tiny head resting on his shoulder. Of all that he’s tried to forget, he allows himself, without reservation, without guilt, the reprieve of this one memory. The curve of her neck against his, paired in the concave and convex of tenderness, as if they were two organs of a single anatomy.

Why are you so soft? he’d ask, and always she’d exclaim, Because I have spinning moonlets! He’d laugh then at the sagacity with which she articulated her illogic, as if it were some scientific truth or ancient wisdom whose profound meaning eluded him. Later, at an age when she could’ve explained the mystery of her pronouncement, he reminded her of those words, but she’d forgotten she’d even uttered them. Oh, Papa, I’m not a baby anymore. She spoke with a maturity that pierced him to the core. She might as well have said, Oh, Papa, I don’t need you anymore. Her eyes, he remembers, took on the detachment of one who’d learned to live with her abandonment, and he grieved her lost innocence, yearned for his baby girl, for the complete trust with which she’d once regarded him.

Something fluid and irrepressible rushes from deep within him and pools behind his eyes. He tries pushing it back. He can’t allow himself the consolation of such emotion. Sorrow is the entitlement of the inculpable. He has no claim on it, no right to grief. After all, what has he lost? Nothing. Nothing he wasn’t willing to give up then. Still, he can’t help but feel it, whatever it may be, sorrow or repentance. It flows out of him, like the season’s accumulated rain, meandering through the gorges and gullies of his disfigured face, cutting deeper into the geography of his guilt.

He runs his fingertips along the thin ridge, where the lesion has long healed. The scar, a shade lighter than the rest of his brown skin, extends crosswise from the bridge of his nose to his lower left cheek, giving the impression of two conjoined countenances, the left half dominated by his cataract eye, the right by smaller grooves and slash marks.

If his daughter saw him now, would she compare the jaggedness of his face to the surface of the moon? How would she describe the crudeness of his appearance? Would she see poetry in it? Find some consolably mysterious expression for its irreparable ruin? He never did make the connection between the softness of her skin and her imaginary moonlets. Now he is left to guess she probably associated the distant velvety appearance of the full moon with the caress of sleep, the lure of dreams that causes one’s body to relax and soften. But even this is too rational a deduction, for he cannot trust his memories of the full moon to make such a leap. The last moon he saw clearly was more than two decades ago, the evening Sokhon died in Slak Daek, one among many of Pol Pot’s secret security prisons across the country, each known only by their coded euphemism as sala. School. That evening, at Sala Slak Daek, the moon was bathed not in gentle porous light but in the glaring hue of Sokhon’s blood. Blood that now tinges his one-eyed vision and sometimes alters the tone and texture of his memories, the truth.

He closes both eyes, for the effort of keeping them open has begun to strain the muscles and nerves of the right one, as if the left eye, unaware of its uselessness, its compromised existence, continues to strive as the right eye does. Sometimes he thinks this is the sum of his predicament: he is dead but his body has yet to be aware of his death.

He reaches into the pocket of his cotton tunic hanging on a bamboo peg above his pillow and withdraws a cone-shaped plectrum made to put over the fingertip. In the old days, this would be crafted from bronze or, if one was a wealthy enough musician, from silver or gold. But this plectrum is fashioned out of a recycled bullet casing. Art from war, said Narunn, the man who gave it to him, a doctor who treats the poor and sometimes victims of violence and torture; who, upon examining his eyes, informed him that the cataract covering his left pupil was caused by untreated “hyphema.” An English word, the Old Musician noted. A medical term. A vision clouded by spilled blood. Or as the young doctor explained, Hemorrhaging in the front of your eye, between the cornea and the iris. Caused by blunt trauma. I believe yours happened at a time when there was no means of treatment. The doctor did not inquire what might’ve been the source of the trauma, as if the lesions and scars on the Old Musician intimated the blunt force of ideology, that politics is not mere rhetoric in this place of wars and revolutions and violent coups but a bludgeon with which to forge one’s destiny.

Indeed the doctor was kind enough not to interrogate. Instead he revealed to the Old Musician that the brass plectrum was made by a young woman who’d lost half her face in an acid attack, who worked to reconstruct her life, if not her visage, by learning to make jewelry in a rehabilitation program for the maimed and the handicapped. Hope is a kind of jewel, don’t you think? his young friend pondered aloud. At once metal-hard and malleable . . .

Certainly it is the only recyclable currency, the Old Musician thinks, in a country where chaos can suddenly descend and everything, including human life, loses all value.

He places the plectrum over the tip of the ring finger of his right hand, the brass heavy and cool against his nailless skin. It refuses to grow back, the nail of this one finger, the lunula destroyed, a moon permanently obliterated by one smash of his interrogator’s pistol. The other fingernails are thick and deformed, some filling only half of the nail beds. He’s often surprised that he can still feel with these digits, as if the injuries they sustained decades ago heighten their wariness of contact, sabotage.

He tilts the sadiev so that it lies diagonally across his torso, the open side of the cut-gourd sound box now covering the area of his chest where his heartbeats are most pronounced, its domed chamber capturing his every tremor and stirring.

Ksae diev, some call it. He dislikes it, the harshness of the ks against his throat, as if the solidity of the first consonant pressed against the evanescence of the second inevitably leads to a betrayal of sound. He much prefers sadiev, the syllables melting into each other so that it’s barely a whisper, delicate and fleeting, much like the echo it produces.

Eyes still closed, he takes a deep breath as he would before every performance, diving past the noise in his head, the surging memories, his plagued conscience, until he reaches only silence. Then tenderly, with the ring finger of his right hand, the brass plectrum securely in place, he begins to pluck the lower part of the string, while higher up the fingers of his left weave an intricate dance. He plays the song he wrote for his daughter, upon her entry into his world, into his solitary existence as a musician. I thought I was alone. I walked the universe, looking for another . . . He remembers the day he brought her home from the hospital, her breath so tenuous still that he wanted to buttress it with notes and words. I came upon a reflection . . . and saw you standing at the fringes of my dream.

He adjusts the sadiev slightly on his chest. He often dreams of her. Not his daughter. But the little girl to whom this lute rightly belongs. Except she’s no longer a little girl, the three-year-old he once met . . . He wonders about the person she’s become, the woman she’s grown into. He dares not confuse one with the other, the young daughter he lost long ago and the woman he now waits to meet. They’re not the same person, he reminds himself. They are not. And you, you are not him. Can never be him. The father she lost.

Sometimes, though, his memory rebels. It contrives a game, tricking him into believing that the past can be altered, that he can make up for the missing years, give her back what he stole from her. He can amend—atone. But for what exactly? A betrayal of oneself, one’s conscience? Was that what he’d hoped when he decided to write to her? To seek forgiveness for his crimes? Or was it simply, as he said, that he wished to return the musical instruments her father had left for her?

He thinks again of the letter, not what it said, but what it was on the verge of saying, what it almost revealed. I knew your father. He and I were . . . His failing eyesight had required him to enlist the help of the young doctor to write those words. He told Dr. Narunn to cross out the incomplete sentence. When he’d finished dictating the rest of the letter, the doctor wanted to copy it onto fresh, clean paper, without the crossed-out words. The Old Musician would not allow it. He’d send it as it was, with the mistake, as if he wanted her to see the duplicity of his mind, the treachery of his thoughts. He and I were . . . What they were—men, animals, two sides of a single reality—was destroyed with one deliberate stroke, the laceration made by a moving blade.

He glides the fingers of his left hand closer to the gourd sound box, producing a periodic overtone, like an echo or a ripple in the pond. I thought I was alone. I walked the universe, looking for your footsteps. I heard my heart echo . . . and felt you knocking on the edge of my dream.

The quality of each note—its resonance and tone—varies as he slides the half-cut gourd across his chest. He plucks faster and harder, reaching a crescendo. Then, in three distinct notes, he concludes the song.

He feels his way in the confined space of the wooden cottage, hands groping in the dark, searching among the shadows through the blurred vision of his one good eye for the sadiev. The lute has called out to him in his dream, plucking its way persistently into his consciousness, until he’s awake, aware of its presence beside him. His fingers find the instrument. It lies aslant on the bamboo bed, deeply reposed in its dreamlessness. His fingers inadvertently brush against the single copper string, coaxing a soft ktock, similar to the click of a baby’s tongue. The Old Musician is almost blind, his left eye damaged long ago by a bludgeon and his right by age. He relies much on his senses to see, and now he sees her, feels her presence, not as a ghostly apparition overwhelming the tiny space of his cottage, nor as a thought occupying his mind, but as a longing on the verge of utterance, incarnation. He feels her move toward him. She who will inherit the sadiev, this ancient instrument used to invoke the spirits of the dead, as if in that solitary note, he has called her to him.

He lifts the lute to his chest, rousing it from its muted sleep, holding it as he often held his small daughter a lifetime ago, her heart against his heart, her tiny head resting on his shoulder. Of all that he’s tried to forget, he allows himself, without reservation, without guilt, the reprieve of this one memory. The curve of her neck against his, paired in the concave and convex of tenderness, as if they were two organs of a single anatomy.

Why are you so soft? he’d ask, and always she’d exclaim, Because I have spinning moonlets! He’d laugh then at the sagacity with which she articulated her illogic, as if it were some scientific truth or ancient wisdom whose profound meaning eluded him. Later, at an age when she could’ve explained the mystery of her pronouncement, he reminded her of those words, but she’d forgotten she’d even uttered them. Oh, Papa, I’m not a baby anymore. She spoke with a maturity that pierced him to the core. She might as well have said, Oh, Papa, I don’t need you anymore. Her eyes, he remembers, took on the detachment of one who’d learned to live with her abandonment, and he grieved her lost innocence, yearned for his baby girl, for the complete trust with which she’d once regarded him.

Something fluid and irrepressible rushes from deep within him and pools behind his eyes. He tries pushing it back. He can’t allow himself the consolation of such emotion. Sorrow is the entitlement of the inculpable. He has no claim on it, no right to grief. After all, what has he lost? Nothing. Nothing he wasn’t willing to give up then. Still, he can’t help but feel it, whatever it may be, sorrow or repentance. It flows out of him, like the season’s accumulated rain, meandering through the gorges and gullies of his disfigured face, cutting deeper into the geography of his guilt.

He runs his fingertips along the thin ridge, where the lesion has long healed. The scar, a shade lighter than the rest of his brown skin, extends crosswise from the bridge of his nose to his lower left cheek, giving the impression of two conjoined countenances, the left half dominated by his cataract eye, the right by smaller grooves and slash marks.

If his daughter saw him now, would she compare the jaggedness of his face to the surface of the moon? How would she describe the crudeness of his appearance? Would she see poetry in it? Find some consolably mysterious expression for its irreparable ruin? He never did make the connection between the softness of her skin and her imaginary moonlets. Now he is left to guess she probably associated the distant velvety appearance of the full moon with the caress of sleep, the lure of dreams that causes one’s body to relax and soften. But even this is too rational a deduction, for he cannot trust his memories of the full moon to make such a leap. The last moon he saw clearly was more than two decades ago, the evening Sokhon died in Slak Daek, one among many of Pol Pot’s secret security prisons across the country, each known only by their coded euphemism as sala. School. That evening, at Sala Slak Daek, the moon was bathed not in gentle porous light but in the glaring hue of Sokhon’s blood. Blood that now tinges his one-eyed vision and sometimes alters the tone and texture of his memories, the truth.

He closes both eyes, for the effort of keeping them open has begun to strain the muscles and nerves of the right one, as if the left eye, unaware of its uselessness, its compromised existence, continues to strive as the right eye does. Sometimes he thinks this is the sum of his predicament: he is dead but his body has yet to be aware of his death.

He reaches into the pocket of his cotton tunic hanging on a bamboo peg above his pillow and withdraws a cone-shaped plectrum made to put over the fingertip. In the old days, this would be crafted from bronze or, if one was a wealthy enough musician, from silver or gold. But this plectrum is fashioned out of a recycled bullet casing. Art from war, said Narunn, the man who gave it to him, a doctor who treats the poor and sometimes victims of violence and torture; who, upon examining his eyes, informed him that the cataract covering his left pupil was caused by untreated “hyphema.” An English word, the Old Musician noted. A medical term. A vision clouded by spilled blood. Or as the young doctor explained, Hemorrhaging in the front of your eye, between the cornea and the iris. Caused by blunt trauma. I believe yours happened at a time when there was no means of treatment. The doctor did not inquire what might’ve been the source of the trauma, as if the lesions and scars on the Old Musician intimated the blunt force of ideology, that politics is not mere rhetoric in this place of wars and revolutions and violent coups but a bludgeon with which to forge one’s destiny.

Indeed the doctor was kind enough not to interrogate. Instead he revealed to the Old Musician that the brass plectrum was made by a young woman who’d lost half her face in an acid attack, who worked to reconstruct her life, if not her visage, by learning to make jewelry in a rehabilitation program for the maimed and the handicapped. Hope is a kind of jewel, don’t you think? his young friend pondered aloud. At once metal-hard and malleable . . .

Certainly it is the only recyclable currency, the Old Musician thinks, in a country where chaos can suddenly descend and everything, including human life, loses all value.

He places the plectrum over the tip of the ring finger of his right hand, the brass heavy and cool against his nailless skin. It refuses to grow back, the nail of this one finger, the lunula destroyed, a moon permanently obliterated by one smash of his interrogator’s pistol. The other fingernails are thick and deformed, some filling only half of the nail beds. He’s often surprised that he can still feel with these digits, as if the injuries they sustained decades ago heighten their wariness of contact, sabotage.

He tilts the sadiev so that it lies diagonally across his torso, the open side of the cut-gourd sound box now covering the area of his chest where his heartbeats are most pronounced, its domed chamber capturing his every tremor and stirring.

Ksae diev, some call it. He dislikes it, the harshness of the ks against his throat, as if the solidity of the first consonant pressed against the evanescence of the second inevitably leads to a betrayal of sound. He much prefers sadiev, the syllables melting into each other so that it’s barely a whisper, delicate and fleeting, much like the echo it produces.

Eyes still closed, he takes a deep breath as he would before every performance, diving past the noise in his head, the surging memories, his plagued conscience, until he reaches only silence. Then tenderly, with the ring finger of his right hand, the brass plectrum securely in place, he begins to pluck the lower part of the string, while higher up the fingers of his left weave an intricate dance. He plays the song he wrote for his daughter, upon her entry into his world, into his solitary existence as a musician. I thought I was alone. I walked the universe, looking for another . . . He remembers the day he brought her home from the hospital, her breath so tenuous still that he wanted to buttress it with notes and words. I came upon a reflection . . . and saw you standing at the fringes of my dream.

He adjusts the sadiev slightly on his chest. He often dreams of her. Not his daughter. But the little girl to whom this lute rightly belongs. Except she’s no longer a little girl, the three-year-old he once met . . . He wonders about the person she’s become, the woman she’s grown into. He dares not confuse one with the other, the young daughter he lost long ago and the woman he now waits to meet. They’re not the same person, he reminds himself. They are not. And you, you are not him. Can never be him. The father she lost.

Sometimes, though, his memory rebels. It contrives a game, tricking him into believing that the past can be altered, that he can make up for the missing years, give her back what he stole from her. He can amend—atone. But for what exactly? A betrayal of oneself, one’s conscience? Was that what he’d hoped when he decided to write to her? To seek forgiveness for his crimes? Or was it simply, as he said, that he wished to return the musical instruments her father had left for her?

He thinks again of the letter, not what it said, but what it was on the verge of saying, what it almost revealed. I knew your father. He and I were . . . His failing eyesight had required him to enlist the help of the young doctor to write those words. He told Dr. Narunn to cross out the incomplete sentence. When he’d finished dictating the rest of the letter, the doctor wanted to copy it onto fresh, clean paper, without the crossed-out words. The Old Musician would not allow it. He’d send it as it was, with the mistake, as if he wanted her to see the duplicity of his mind, the treachery of his thoughts. He and I were . . . What they were—men, animals, two sides of a single reality—was destroyed with one deliberate stroke, the laceration made by a moving blade.

He glides the fingers of his left hand closer to the gourd sound box, producing a periodic overtone, like an echo or a ripple in the pond. I thought I was alone. I walked the universe, looking for your footsteps. I heard my heart echo . . . and felt you knocking on the edge of my dream.

The quality of each note—its resonance and tone—varies as he slides the half-cut gourd across his chest. He plucks faster and harder, reaching a crescendo. Then, in three distinct notes, he concludes the song.

Recenzii

“Music of the Ghosts is a moving and often gripping exploration of Cambodia’s Khmer Rouge regime and its aftermath. Ratner relentlessly shows the devastating impact of traumatic history on families and the nation, but leaves us with a carefully measured hope for insight and renewal.”

"Music of the Ghosts is a novel of extraordinary humanity in the face of unforgivable culpability. Here, acts of friendship transform into acts of rebellion, and storytelling reveals not only the past, but this moment, when reconciliation and forgiveness are so desperately needed. Vaddey Ratner speaks to the choices confronting all of us, and she does so with compassion, forewarning and courageous wisdom."

“Few atrocities compare with the almost unimaginable devastation brought to Cambodia by Pol Pot. But Vaddey Ratner, a survivor of the Khmer Rouge regime, has not only created here an unforgettable vision of revolution and genocide, but also a moving portrayal of lives interwoven by loss, Buddhist wisdom and, most important of all, redemption. Music of the Ghosts is a powerful performance.”

“Vaddey Ratner’s new novel, Music of the Ghosts, is an extraordinary achievement. It is deeply haunting in its evocation of place, profound in the directness with which it confronts age old questions of guilt, regret, and loss, and staggeringly beautiful in its masterful lyricism. A book like this doesn’t come around very often. I hope everyone will read it.”

"A powerful examination of the burdens of survival. Ratner writes with precision and lyricism about lives damaged in one of the darkest episodes in history. A timely, redemptive work."

"Lush with tropical heat and heated emotions...impossible to put down."

"Powerful...haunting, unforgettable."

“Ratner’s sophomore title should place her squarely alongside Yiyun Li, Khaled Hosseini, and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, writers who have miraculously rendered inhumanity into astonishingly redemptive literary testimony.”

“Captivating . . . a tragic odyssey of love, loss, and forgiveness in the wake of unspeakable horrors. . . . [Ratner] weaves a moving tale of hope and heartbreak that will accompany readers long after they finish the last page.”

"Ratner stirs feeling--sorrow, sympathy, pleasure--through language so ethereal in the face of dislocation and loss that its beauty can only be described as stubborn....Music of the Ghosts has itself been fashioned by a writer scarred by war, a writer whose ability to discern the poetic even in brutal landscapes and histories may be the gift that helped her reassemble the fragments of a self and a life after such shattering suffering."

"A sensitive, melancholy portrait of the inheritance of survival--the loss and pain as well as the healing....an affecting novel, filled with sorrow and a tender, poignant optimism."

"The deeper I read into Music of the Ghosts, the more engrossed I became in the tangled skeins that define her characters' lives, in the history that her fiction illuminates, in the perceptions that could break a reader's heart...That's the stuff of war, and Ratner does not hold back....But she is equally committed to revealing, for us, the endless ways that families can be forged and broken hearts held."

“Themes of loss and hope, survivors and the metaphorical ghosts that follow them, crescendo into a rich finale celebrating the resilience of the human spirit and the permanence of love.... Readers will shed happy and sad tears as they savor this reminder that regardless of past hurts, life is ours to live.”

“A poignant new novel focusing not on the horrors themselves (as was the focus of her fictional debut), but of the implications and stakes for survivors.”

“Her lavish storytelling — complete with pure, honest language and lush, stunning description — is how Ratner will draw readers into her intricately crafted story. Her distinctive, vivid characters and authentic scenes of both peace and war are the highlights of the story. Her skillful weaving of the past and present lives of both Teera and the Old Musician, strung together by poignant musical references, will mesmerize readers. A story that both captures and reveals the heart of its characters, Ratner’s latest is a beautiful gem of a read.”

"Lyrical...beautiful and haunting...filled with truth both emotional and factual."

"Told with careful lyricism...Occasionally calling to mind Things Fall Apart, another novel about collapsed societies...evokes a world with ghosts aplenty, but far less apt by Ratner's hand to be dismissed as a sideshow."

"A mellifluous composition for two voices in echoing counterpoint."

“A timely and haunting narrative about the lives facing so many refugees, this riveting novel couldn't have come at a better time.”

"Music of the Ghosts is a novel of extraordinary humanity in the face of unforgivable culpability. Here, acts of friendship transform into acts of rebellion, and storytelling reveals not only the past, but this moment, when reconciliation and forgiveness are so desperately needed. Vaddey Ratner speaks to the choices confronting all of us, and she does so with compassion, forewarning and courageous wisdom."

“Few atrocities compare with the almost unimaginable devastation brought to Cambodia by Pol Pot. But Vaddey Ratner, a survivor of the Khmer Rouge regime, has not only created here an unforgettable vision of revolution and genocide, but also a moving portrayal of lives interwoven by loss, Buddhist wisdom and, most important of all, redemption. Music of the Ghosts is a powerful performance.”

“Vaddey Ratner’s new novel, Music of the Ghosts, is an extraordinary achievement. It is deeply haunting in its evocation of place, profound in the directness with which it confronts age old questions of guilt, regret, and loss, and staggeringly beautiful in its masterful lyricism. A book like this doesn’t come around very often. I hope everyone will read it.”

"A powerful examination of the burdens of survival. Ratner writes with precision and lyricism about lives damaged in one of the darkest episodes in history. A timely, redemptive work."

"Lush with tropical heat and heated emotions...impossible to put down."

"Powerful...haunting, unforgettable."

“Ratner’s sophomore title should place her squarely alongside Yiyun Li, Khaled Hosseini, and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, writers who have miraculously rendered inhumanity into astonishingly redemptive literary testimony.”

“Captivating . . . a tragic odyssey of love, loss, and forgiveness in the wake of unspeakable horrors. . . . [Ratner] weaves a moving tale of hope and heartbreak that will accompany readers long after they finish the last page.”

"Ratner stirs feeling--sorrow, sympathy, pleasure--through language so ethereal in the face of dislocation and loss that its beauty can only be described as stubborn....Music of the Ghosts has itself been fashioned by a writer scarred by war, a writer whose ability to discern the poetic even in brutal landscapes and histories may be the gift that helped her reassemble the fragments of a self and a life after such shattering suffering."

"A sensitive, melancholy portrait of the inheritance of survival--the loss and pain as well as the healing....an affecting novel, filled with sorrow and a tender, poignant optimism."

"The deeper I read into Music of the Ghosts, the more engrossed I became in the tangled skeins that define her characters' lives, in the history that her fiction illuminates, in the perceptions that could break a reader's heart...That's the stuff of war, and Ratner does not hold back....But she is equally committed to revealing, for us, the endless ways that families can be forged and broken hearts held."

“Themes of loss and hope, survivors and the metaphorical ghosts that follow them, crescendo into a rich finale celebrating the resilience of the human spirit and the permanence of love.... Readers will shed happy and sad tears as they savor this reminder that regardless of past hurts, life is ours to live.”

“A poignant new novel focusing not on the horrors themselves (as was the focus of her fictional debut), but of the implications and stakes for survivors.”

“Her lavish storytelling — complete with pure, honest language and lush, stunning description — is how Ratner will draw readers into her intricately crafted story. Her distinctive, vivid characters and authentic scenes of both peace and war are the highlights of the story. Her skillful weaving of the past and present lives of both Teera and the Old Musician, strung together by poignant musical references, will mesmerize readers. A story that both captures and reveals the heart of its characters, Ratner’s latest is a beautiful gem of a read.”

"Lyrical...beautiful and haunting...filled with truth both emotional and factual."

"Told with careful lyricism...Occasionally calling to mind Things Fall Apart, another novel about collapsed societies...evokes a world with ghosts aplenty, but far less apt by Ratner's hand to be dismissed as a sideshow."

"A mellifluous composition for two voices in echoing counterpoint."

“A timely and haunting narrative about the lives facing so many refugees, this riveting novel couldn't have come at a better time.”