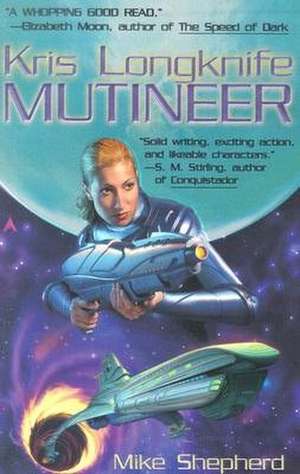

Mutineer: Kris Longknife Novels, cartea 01

Autor Mike Shepherden Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 dec 2003 – vârsta de la 18 ani

Preț: 57.62 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 86

Preț estimativ în valută:

11.03€ • 11.44$ • 9.19£

11.03€ • 11.44$ • 9.19£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 06-20 martie

Livrare express 19-25 februarie pentru 17.85 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780441011421

ISBN-10: 044101142X

Pagini: 389

Dimensiuni: 107 x 172 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.19 kg

Editura: Ace Books

Seria Kris Longknife Novels

ISBN-10: 044101142X

Pagini: 389

Dimensiuni: 107 x 172 x 28 mm

Greutate: 0.19 kg

Editura: Ace Books

Seria Kris Longknife Novels

Notă biografică

"Mike Shepherd" is a pseudonym for Mike Moscoe. Moscoe, a former civil servant, lives in the Pacific Northwest with his wife Ellen and now writes full-time. As Mike Shepherd, he has written the five very popular Kris Longknife military science fiction adventures, with more to come!

Extras

1 “There’s a terrified child down there.”

Captain Thorpe’s baritone reverberated off the hard metal walls of the Typhoon’s drop bay. Marines, a moment before intent on checking their battle suits, their weapons, their souls for this rescue mission, hung on his every word. Ensign Kris Longknife divided her attention; part of her stood back, studying the impact of his speech on the men and women she would soon lead. In her short twenty-two-year life, she’d heard a lot of fancy oratory. Another part of her listened to her commander’s words, felt them roll over her, into her. It had been a long time since mere words had raised the hackles on her neck, made her want to rip some bastard limb from limb.

“The civilians tried to get her back.” Kris measured his pause. He came in right on the downbeat. “They failed. Now they’ve called for the dogs.”

The marines around Kris growled for their skipper. She’d only worked with them for four days; the Typhoon had sortied on two hours’ notice! Captain Thorpe had gotten them away from space dock, short half the crew and without a marine lieutenant to command the drop platoon. Now a boot ensign named Longknife was surrounded by marines with three to twelve years in the Corps, champing at the bit to do something definite and dangerous.

“You’ve trained. You’ve sweated.” The captain’s words had the staccato of a machine gun. “You’ve drilled for this moment since you joined the Corps. You could rescue that kidnapped girl with your eyes closed.” In the dim light of the drop bay, eyes gleamed with inner fire. Jaws tensed; hands closed in tight fists. Kris glanced down; so were hers. Yes, these troops were ready, all except one boot ensign. Dear God, don’t let me screw up, Kris prayed silently.

“Now drop, Marines. Kick some terrorist butt, and put that little girl back in her mother’s arms where she belongs.”

“Ooh-rah,” came back from twelve hyped men and women as the captain slow marched for the exit. Well, eleven hyped marines and one scared ensign. Kris put the same angry confidence into her shout as she heard from the rest. Here was none of the calm, the cool of Father’s political speeches. Here was why Kris had joined the Navy. Here was something real; something she could get her hands on and make happen. Enough of endless talk and nothing done. She grinned. If you could see me now, Father. You said the Navy was a useless waste of time, Mother. Not today!

Kris took a deep breath as her platoon turned back to their preparations. The smell of armor, ammunition, oil, and honest human sweat gave her a rush. This was her mission and her squad, and she would see that one little girl got home safe and sound. This child would live.

As the memory of another child rose to fill her mind’s eye, Kris stomped on the thought. She dared not go there.

Captain Thorpe paused in his exit march right in front of her. Eye to eye, he leaned into her face. “Keep out of your head, Ensign,” he growled in a whisper. “Trust your gut. Trust your platoon and Gunny. They’re good. The commodore thinks you have what it takes, even if you are one of those Longknifes. Show me what you’ve got. Take those bastards down hard. But if you’re as empty as your old man, let Gunny know before you funk out on us, and he’ll finish the mission. And I’ll drop you back in your momma’s lap in time for the next debutantes’ ball.”

Kris stared back at him, her face frozen, her gut a throbbing knot. He’d been riding her since she came aboard, never happy with her, always picking at her. She would show him. “Yes, sir,” she shouted in his face.

Around her, the troops grinned, figuring the skipper had a few choice words for the boot ensign, none knowing just how choice. The captain snickered. A scowl or a snicker or a growl was all she’d ever seen on his face since coming aboard. Was there a different crinkle to his eyes, a new uptwist to his lips? He turned before she could read him better.

It wasn’t her fault Father had signed all Wardhaven’s legislation for the last eight years. She had nothing to do with her great-grandparents splashing the family name all over the history books. Let the captain try growing up in shadows like those. He’d be just as desperate as Kris was to make her own name, find her own place. That was why she joined the Navy.

With a shiver Kris tried to shake off the fear of failure. She turned to face her locker and tried again to adjust the standard-issue, size three battle spacesuit to fit. Six feet tall and too small everywhere else was her usual requirements for a suit. She’d never had a civilian suit that didn’t leave her plenty of room for her pet computer to conform around her shoulders and down her arms, but those suits weren’t semirigid plasta-steel a centimeter thick. Nelly, worth more than all the computers on the Typhoon and probably fifty times as capable, was a problem in battle armor. Marines were expected to be lean as well as mean; nothing extra was allowed anywhere. Kris tried slipping the main bulk of the computer down to her chest. She didn’t carry much there, and most marine males seemed to be a bit bulky in that spot. Resealing herself in, she rotated her shoulders, bent, then stooped. Yes, that worked. She put on the helmet, rotated it until she got a firm click. With the faceplate down, the suit was a bit warm, but she’d been hot before.

“Krissie, can I have an ice cream?” Eddy wheedled. It was a hot spring day on Wardhaven, and they’d run to the park, leaving Nanna well behind them.

Kris fumbled in her pocket. She was the big sister; she was expected to plan ahead now, just like big brother Honovi had done for her when she was just a little kid. Kris had enough coins for two ice creams. But Father insisted that planning ahead included making things last. “Not now,” Kris insisted. “Let’s go see the ducks.”

“But I want an ice cream now,” came in as much of a wail as an out-of-breath six-year-old could muster.

“Come on, Nanna’s almost here. Race you to the duck pond.” Which got Eddy’s feet moving even before Kris finished the challenge. She beat him, of course, but only by as much as a ten-year-old big sister should beat a six-year-old kid brother.

“Look, the swans are back.” Kris pointed at the four huge birds. So they walked along the pond, not too far behind the old man with the corn who always fed the birds. Kris was careful to keep Eddy from getting too near to the water. She must have done a good job because when Nanna finally caught up with them, she didn’t give Kris a lecture about how deep the pond was.

“I want an ice cream,” Eddy demanded again with the single-mindedness of his few years.

“I don’t have any money,” Nanna insisted.

“I do,” Kris put in proudly. She had planned ahead, just like Father said smart people should.

“Then you go buy the ice cream,” Nanna grumbled.

Kris skipped off, so sure she would be seeing them again that she didn’t even look back.

There was a tap at her shoulder. With a shiver, she turned to see a freckled face and raised her faceplate in time to be met with a “Need help, short fork?”

The drop bay was busy and noisy, and her shiver went unnoticed. She managed the cheery “No way, wooden spoon,” reply the infectious grin and challenge demanded. Ensign Tommy Li Chin Lien had been born to a family of Santa Maria asteroid miners. Rather than hang around that isolated world, he’d joined the Navy to see the galaxy, thereby greatly disappointing his folks and, per his great-grandmother, his ancestors.

At Officer Candidate School, they’d passed hours swapping stories about how their parents had stormed and ranted against their career choice. Kris was surprised by how fast they became friends, one from supersophisticated Wardhaven, the other that crazy blend of Irish and Chinese that so much of Santa Maria’s working class still held to.

Right now, Tommy waved his universal tester in Kris’s face. Raised in vacuum, he distrusted air and gravity and viewed mud-raised people like Kris as hopeless optimists, dependent on him for the proper paranoia toward space. Kris raised her left arm for Tommy to plug his black box into the battle suit she’d been issued. While he ran his checks, Kris worked with Nelly, running her personal computer through interface tests with the command net. Auntie Tru, now retired from her job as Wardhaven’s Info War Chief, had helped Kris with Nelly’s interface, as she’d done with most of Kris’s math and computer homework for as long as Kris could remember. Nelly lit up Kris’s heads-up display with every report or screen authorized to a boot ensign on a mission . . . and a few it was better the skipper did not know Kris had access to. Kris and Nelly finished about the same time Tommy detached his tester from Kris. She flipped up her faceplate.

“Your camouflage adjustment is about five nanoseconds below optimum, but it meets Navy standards,” Tommy grumbled. The Navy rarely met his expectations for perfection. “Your coolant system isn’t all that far into the green, either.”

“I’m more worried about my heater. It’s arctic tundra where I’m headed, haven’t you heard?” She grinned.

He refused to swallow his scowl for her attempt at a Santa Maria brogue. “And there’s a bad gasket in there somewhere.” They’d been over that one before; one of the battle suit’s jelly seals was a slow leaker, but every suit aboard had at least one bum seal. It was a bitter joke among the troops; good seals went to the civilian market, weak ones went to lowest-bid government contracts.

“I’m not working the asteroids, Tommy. I won’t be living in this suit for a month.” Kris gave the standard reply the procurement chiefs gave her father. The prime minister of Wardhaven always accepted it. But then, he didn’t do drop missions. Today, his daughter was. “I’ll only be in vacuum an hour, two at the most. Sequim’s atmosphere is good.”

“Mud hen,” Tommy answered in disgust.

“Space head,” Kris shot back, giving Tommy one of his own trademark grins, then turned to the Light Assault Craft that would be carrying her and her squad. It was the minimum vehicle that could get you from orbit to the deck, not much more than a heat shield that doubled as a wing and a flip-on top that was just there for stealth. Then again, Kris had raced in smaller skiffs. “This check out?” she asked, serious once more.

“Didn’t I test it four times?” Tommy grinned. “Didn’t it pass four times? Your humble servant will get you there.” Which only left Kris struggling to keep hold of her temper. The Navy trusted the marines to put their asses on the line, but not with the car keys. It would be Tommy’s job to fly the two LACs from the Typhoon in orbit to the ground, all except for two or three minutes when ionization took the two LACs out of radio touch—and they’d be on autopilot for that. All the while, Kris and her eleven marines were supposed to sit there dumb and bored. That was just one part of the approved plan she would like to change. But a boot ensign does not change plans that her skipper and his Gunny Sergeant like.

“Help me on with my kit,” she told Tommy. Along the bay, the platoon members were paired up, checking each other’s suits, loading them up with weapons and drop gear. Corporal Santo went down Gunny’s squad, Corporal Li checked Kris’s. Gunny would double-check them; then Kris would triple-check.

Kris’s load was a tad lighter than her teammates’ since Nelly weighed in at half of a standard-issue Navy personal computer while holding all the command, control, communications, and intelligence—C3I in military speak—that an ensign could ask for. Still, hanging from her armor or carefully stowed in her pack were rocket-propelled grenades of many flavors; six spare magazines for her M-6, half of them rounds of nonlethal intent, the others real ones; as well as water, first aid, and food. Marines never left home without lugging a ton of stuff. Fully loaded, again Kris rotated her shoulders, twisted her hips, checked the load if not for comfort at least for problems. She’d carried more backpacking through the Blue Mountains on Wardhaven during college vacations. Those carefree months of outdoor living was one of the reasons she was here.

Tommy eyed her as she did a deep knee squat and bounced back up. “You good for this?”

“Everything’s in place. Not too heavy.”

“You good for this business? Rescuing a kidnapped kid.” The grin was gone; she saw what the Santa Marian looked like serious.

“I’m good for this, Tom. I’m the best Navy small arms weapons qualifications on this boat. I’ve got the best Navy physical training scores, too. The skipper’s right. I’m the best he’s got. And Tommy, I want this.”

“Ensign Lien to the bridge,” came over the ship’s MC-1, ending any further questions. Tommy clapped her on the back. “The luck of the little people and God go with you,” he said as he headed for the hatch.

“No spare seat for Him in an LAC,” Kris shot back over her shoulder, another salvo in their long-running debate. But Kris was already trailing Gunny, rechecking the fall of gear, reverifying weapons loads. She finished a second behind him.

He went over her kit, and she went over his. He tightened one of her straps and growled, “You’ll do, ma’am.” She found nothing to modify on him; she hadn’t expected to. Gunny had practiced for this moment for sixteen years. That this was his first live-fire mission in all that time didn’t seem to bother him or Captain Thorpe.

“Let’s drop, team!” Kris called to her loaned platoon.

With a shout of “Ooh-rah” the two squads turned in unison to face opposite bulkheads and board their two Light Assault Crafts. Kris went down the line of her squad one more time, checking their restraining harnesses and the arrangement of their gear as they settled into their low seats in the LAC. All readouts showed green. Still, Kris gave each a good hard tug. That webbing was the only thing holding her troopers in. Satisfied, she settled her own rump onto the low composite seat in this minimum spacecraft and stretched her legs out ahead of her, careful to avoid the control pedals. The legs of the tech seated behind her surrounded her. Kris had once tried a toboggan. Mother had refused in horror when Kris asked to take a ride downhill. That toboggan was roomy compared to an LAC.

She rechecked to make sure her harness was firmly attached to the LAC’s narrow keel, checked again to make sure none of her gear was out of place, then pulled the canopy down and felt it click into place. Like so much of the LAC, the canopy was paper thin; it added nothing more than stealth to the craft. Only their drop suits would protect Kris and her troops from the vacuum of space or the heat of reentry.

The control stick began to rotate between Kris’s legs. That would be Tommy running tests. Still, the sight of it moving brought back good memories of some damn fine stick time of her own. She wiggled in her seat and felt the light craft respond to her movements. Bigger than a racing skiff but just as sweet.

Kris banished those distractions by replaying the drop plan in her mind as she waited. These kidnaping sons-a-bitches had a simple plan. They’d snapped up the Sequim General Manager’s sole child during a school outing, then dragged the poor kid off to the northern wilderness before anyone knew what had happened. Ignore the child’s name . . . much too familiar. Only pain there. Quickly Kris returned to tonight’s problem. The approaches to the

kidnappers’ hideout were long, difficult, dangerous—and booby-trapped! So far, the bad guys had outsmarted—and killed—too many good people.

Kris ground her teeth; how had cruds like these gotten their hands on some of the most sophisticated traps and countermeasures in human space? She could understand the traps; humans now frequented planets with very nasty critters. And while she had never hunted big game herself, she was looking forward to this hunt for the most dangerous game. What frosted her was the legal bunk used by specialty stores to excuse their sale of measures and countermeasures that were only going to make her job damn dangerous tonight. Normal people didn’t need electrocardiogram jammers. Why would any good citizen need a decoy device to simulate a human heat signature? Blast it, her suit was warm; sweat was already running down her back.

The day was so hot, the ice cream melted even as Kris trotted toward the duck pond. Kris paused just long enough to give both ice cream cones a quick lick, then felt guilty. “Eddy, I’ve got your ice cream,” she called as she hurried on. She hurried so much that she was well out of the trees and halfway across the vale to the pond before the wrongness of it got through to her. Kris came to a slow halt.

Eddy wasn’t there!

The man with the corn had fallen, half in the water. The ducks gathered around him to pluck at the fallen grain.

Two lumps of clothes doted the vale. In her nightmares that night, Kris would recognize them for agents who had been with her for years. But right then, her eyes were riveted on Nanna. She had fallen down. Her arms and legs splayed around like a rag doll. Even at ten, Kris knew that was all wrong for a real person.

Kris began to scream. She dropped her ice cream cones as she tried to cram her hands in her mouth, bite down hard on knuckles hoping the pain would wake her from this bad dream. Somewhere behind her, a voice shouted into a commlink. “Agents down. Agents down. Dandelion is nowhere in sight. I repeat, Dandelion is missing.”

A flashing red light grabbed Kris’s attention. “You did it again,” she growled at herself as she yanked her thoughts back to the problem at hand. Around her, the drop bay ran through decompression. Air gone, Kris and her troopers breathed only what their drop suits provided. Kris checked all her readouts. Her suit was good, as good as Navy issue got. So were all of her troopers. “Good to go,” she reported.

With a thump to Kris’s rear, the LAC fell into silent, black space. Tommy let them drift for only the moment it took Kris to get a good look at the Typhoon, her smart-metal hide stretched thin to give the crew individual rooms and spin gravity while in orbit. Her bow and stern was proudly painted with the blue and green flag of the Society of Humanity. Then the LAC came alive; the stick moved as Tommy guided both LACs into reentry.

Well, if Tommy was doing the work, Kris could use the time to check the ground situation once more. “Nelly, show me the real time target feed,” Kris subvocalized. The hunting lodge filled Kris’s heads-up display. Several dozen human shadows showed on the infrared detection. Six or eight moved around the building . . . all in pairs. Per the guarantee provided with every human heat decoy sold, there was no way Kris was supposed to know that only five real humans were moving. Thank God the manufacturers had so far stuck to the pledge of silence the government had extracted from them.

For ten years, no bad guys had tumbled to the fact that 98.6 degrees was only the average human temperature. This late at night most people’s body heat was slipping down into the 97s and 96s. In the six upstairs rooms of the lodge, the heat signatures of six little girls lay chained to their beds. Two gunmen sat at opposite ends of the hall, ready at the first sign of rescue to dash into the one room that held the kidnapped girl and kill her. Thanks to the sensors on the fifty-gram Stoolpigeon hovering 1,000 meters above the log cabin, Kris knew there was only one gunman—and which room held the terrified girl.

Terrified! Kris ground her teeth, then looked out of the LAC to rest her eyes on the planet revolving slowly below her. She tried to do anything but touch the nerve that took her again into her little brother’s grave. At least these kidnappers had not buried their victim under tons of manure with a damaged air pipe the only lifeline to the world for a six-year-old kid.

At school, Kris had overheard other students talking, saying that Eddy was dead hours before her parents paid the ransom. She didn’t know the truth of that. There were some reports she just couldn’t read, some media coverage she could never sit through.

What could never be ignored for a moment were the what-ifs. What if Kris hadn’t gone for ice cream? What if the bad guys had had to take down Nanna and Eddy and Kris? What would a wild ten-year-old girl have done to their plans?

Kris shook her head, willed away the images. Stay there too long, and tears came. A spacesuit was no place for tears.

Kris focused on the planet below. The day terminator lay ahead, changing the green and blue cloud-shrouded globe to dark—darkness and storms. A surprise night drop needed thunder to cover the sonic booms, darkness to hide their approach, night to make guards inattentive.

Kris smiled, remembering other planets she’d watched from orbit, a fast racing skiff under her. And her smile slid into a scowl as the memories she’d been struggling to hold at arm’s length for a week came flooding back.

Father vanished from Kris’s life the day after Eddy’s funeral. Off to the office before she awoke, he was rarely home before her bedtime.

Mother was something else. “You’ve been a little savage long enough. Time to make a proper young lady out of you.” That didn’t get Kris off the hook for winning soccer games for Father or showing up for his political parties. But Kris quickly discovered “proper young ladies” not only went to ballet but also accompanied Mother to teas. As the youngest at any tea by twenty years, Kris was bored silly. Then she noticed that some women’s teas smelled funny. It wasn’t long before Kris got a chance to taste them. They tasted funny, too . . . but they made Kris feel better, the parties go faster. It wasn’t long before Kris found what was being added to their tea . . . and how to raid her father’s liquor cabinet or mother’s wine closet.

Somehow, the drinking made the days endurable. Kris didn’t even care when her grades took a nosedive. It didn’t matter; Mother and Father only frowned. Other kids at school had fun things like skiff racing from orbit; Kris had her bottle. Of course, the bottle and the pills Mother’s doctor prescribed to help Kris be more ladylike did not help her soccer game. The coach shook his head and sidelined her as much as he could. Harvey, the chauffeur who took her to all the games, just seemed kind of sad.

But Harvey was grinning the afternoon he picked Kris up from school late. “Your dad’s invited your Great-grampa Trouble to dinner tonight. General Tordon is on Wardhaven for meetings,” Harvey added before she asked. Kris spent the drive home wondering what she’d say to someone straight out of her history books.

Mother was in a snit, overseeing dinner preparations herself and mumbling that legends should stay in the books where they belonged. Kris was sent upstairs to do homework, but she staked out the balcony, reading with one eye and watching the front door with the other. Kris wasn’t sure what to expect. Probably someone ancient, like old Ms. Bracket who taught history and seemed dry and wrinkled enough to have lived it. All of it!

Then Grampa Trouble walked through the front door. Tall and trim, gleaming in undress greens, he looked like he could destroy an Iteeche fleet just by scowling at them. Only he wasn’t scowling. The grin on his face was infectious; Mother was right, he was totally inappropriate for a “proper legend.” And at dinner, the stories he told. After dinner, Kris couldn’t remember a single one of them, at least not completely. But during supper they were all funny, even those that should have been horrifying. Somehow, no matter how bad the odds were or how impossible the situation had been, Grampa Trouble made it sound terribly funny. Even Mother laughed, despite herself. And when supper was over, Kris managed to dodge Mother until she excused herself for her whist club. Kris wanted to hang around this wondrous apparition forever. And when they were alone and he turned his full attention to Kris, she knew why kittens curled up in the sun.

“Your dad tells me you like soccer?” he said, settling into a chair.

“Yeah, pretty much,” Kris answered seating herself ladylike across from her grampa and feeling very grown-up.

“Your mom says you’re very good at ballet.”

“Yeah, pretty much.” Even at twelve, Kris knew she was not holding up her end of the conversation. But what could she say to someone like her grampa?

“I like orbital skiff racing. Ever do any racing?”

“Naw. Some kids at school do.” Kris tasted excitement. Then she remembered herself. “But Mother says it is much too dangerous. And nothing for a proper young lady.”

“That’s interesting,” Grampa Trouble said, leaning back in his chair and stretching his hands upward. “A girl won the junior championship for Savannah last year. She wasn’t much older than you.”

“She wasn’t!” Kris stared, wide-eyed. Even from Grampa, she couldn’t believe that.

“I’ve rented a skiff tomorrow. Want to take a few drops with me?”

Kris fidgeted in her chair. “Mother would never let me.”

Grampa brought his hands to rest on the table, only inches away from Kris’s. “Harvey tells me your mom usually sleeps in on Saturday. I could pick you up at six.” Later, Kris would realize that Grampa Trouble and the family chauffeur were in cahoots on this. But Kris had been too excited by the offer just then to put two and two together.

“Could you?” Kris yelped. She couldn’t remember the last time she’d been up early on her own. She also couldn’t remember the last time she’d done something that wasn’t on Mother or Father’s To-Do List. She couldn’t remember because to do that would be to remember what life was like with Eddy. “I’d love to,” she said.

“One thing,” Grampa Trouble said, reaching across the table to take her small, soft hands in his tanned, calloused ones. His touch was almost electric in its shock. His eyes looked into hers, stripping away the little girl that faked it for so many. Kris sat there, with nothing but herself to hang on to. “Your mother is right. Skiff racing can be dangerous. I only take people riding with me who are stone cold sober. That won’t be a problem for you, will it?”

Kris swallowed hard. She’d been laughing so hard at Grampa Trouble’s stories that she hadn’t stolen a drink at supper. She hadn’t had one since lunch at school. Could she go through the night? “It won’t be a problem,” Kris assured him.

And somehow she made it. It wasn’t easy; she woke up twice crying for Eddy. But she thought about Grampa and all the stories she had overheard from the school kids about how fun it was to see the stars above you and ride a falling star to Earth, and somehow Kris didn’t tiptoe downstairs to Father’s bar.

Kris made it through that night to stand at the top of the stairs and look down at Grampa Trouble so magnificent in his green uniform, waiting patiently for her on the black and white tiles of the foyer. Balanced careful as ever she did in ballet class, Kris went down the stairs, showing Grampa just how sober she was. His smile was a small, tight thing, not at all the open-faced one Father flashed all his political friends. Grampa’s tight little smile meant more to Kris than all she’d gotten from her father or mother.

Three hours later, Kris was suited up and strapped into the front seat of a skiff when Grampa Trouble hit the release and they dropped away from the space station. Oh, what a ride! Kris saw stars so close she could almost touch them. The temptation came to pop her belt, to drift away into the dark, to fall like

a shooting star and make whatever amends she could to dead little Eddy. But she couldn’t do that

to Grampa Trouble after all the trouble he’d gone through to get her here. And the beauty of the unblinking stars grabbed Kris, enveloping her in their cold, silent hug. The pure, lean curves of skiffs on reentry were mathematics in motion. She’d lost her heart . . . and maybe some of her survivor’s self-loathing.

Mother was actually pacing the foyer when they came in late that evening. “Where have you been?” was more an accusation than a question.

“Skiff racing,” Grampa Trouble answered as evenly as he told jokes.

“Skiff racing!” Mother shrieked.

“Honey,” Grampa Trouble said softly to Kris, “I think you better go to your room.”

“Grampa?” Kris started, but Harvey was taking Kris’s elbow.

“And don’t you come down before I send for you.” Mother enforced Grampa’s suggestion. “And what did you think you were doing with my daughter, General Tordon?” Mother said coldly, turning on Grampa.

But Grampa Trouble was already heading toward the great library. “I think it best we finish this conversation out of earshot of little pitchers with big ears,” he said with all the calm Mother lacked.

“Harvey, I don’t want to go to my room,” Kris argued as she and the chauffeur went up the stairs.

“It’s best you do, little friend,” he said. “Your mother’s been stretched quite a ways today. There’s nothing to be gained by you pushing her any further.”

Kris never saw Grampa Trouble again.

But a week later, Judith came into her life, a woman Grampa Trouble would probably have enjoyed meeting. Judith was a psychologist.

“I don’t need a shrink,” Kris told the woman flat out.

“Why’d you throw the soccer game last month?” Judith shot right back.

“I didn’t.” Kris mumbled.

“Your coach thinks you did. Your dad thinks so, too.”

“How would Father know?” Kris asked with all the sarcasm a twelve-year-old could muster.

“Harvey recorded the entire game,” Judith said.

“Oh.”

So they talked, and Kris found that Judith could be a friend. Like when Kris shared that she wanted to do more skiff racing, but Mother would have kittens at the very thought. Instead of agreeing with Mother, Judith asked Kris why Mother shouldn’t have a kitten or two? The thought of Mother with a kitten made Kris laugh, which needed an explanation, and before they were done, Kris had come to realize that what Mother wanted wasn’t always the best, and that the mother of a twelve-year-old girl should have kittens occasionally. Kris went on to win Wardhaven’s junior championship to the prime minister’s delight and Mother’s horror.

“Get out of your head,” Kris growled in Captain Thorpe’s voice and yanked tight on her restraining harness, a life-affirming act that now came naturally to her.

Then Kris’s stomach shot into her throat as her lander turned dervish, spinning to the right as the bottom dropped out from underneath her and the still-blasting thrusters rose above.

“What the hell?” “Who’s driving this bus?” rattled in her ears as Kris grabbed for the wildly gyrating control stick. Aft, Corporal Li restored discipline with a “Pipe down.”

The stick fought Kris, refusing to obey. She punched her commlink to the Typhoon. “Tommy, what the hell is going on?” Her words echoed empty in her helmet; her commlink was as dead as she and her crew would be if she didn’t do something—fast.

Mashing the manual override, Kris took command of her craft. With hardly a thought, her hands went though the motions needed to dampen down the spin and pitch. The LAC was heavier, slower to respond than a skiff. But Kris fought it . . . and it obeyed.

“That’s better,” came from one of the grateful marines behind her. Unless Kris figured out fast where they were and where they were going, this momentary “better” just meant they’d be less shook up when they burned on reentry.

“Nelly, I need skiff navigation, and I need it now.” In a blink, the familiar skiff routines took form on her heads-up. “Nelly, interrogate GPS system. Where am I?” The LAC became a dot on her heads-up, vector lines extended from it. She’d been accelerating rather than decelerating!

“Corporal, get a line-of-sight link to Gunny’s LAC.”

“I’ve been trying, ma’am, but I don’t know where he is.”

Her computer could probably tell Kris where the sergeant should be with respect to them, but Nelly was doing her best to plot a course that would win Kris another championship.

They didn’t hand out skiff trophies just for hitting that dinky ground target. They expected winners to do it in style: be on the dot, use less fuel, take less time. Kris gulped as her heads-up display filled with the harsh challenge ahead. The LAC was out of position and lower on fuel than any skiff she’d ever flown in competition. It would take every ounce of skill Kris had to land her marines anywhere within a hundred kilometers of one terrified little girl.

Kris had raced for trophies. Tightening her grip on the stick, she began a race for a little girl’s life.

Captain Thorpe’s baritone reverberated off the hard metal walls of the Typhoon’s drop bay. Marines, a moment before intent on checking their battle suits, their weapons, their souls for this rescue mission, hung on his every word. Ensign Kris Longknife divided her attention; part of her stood back, studying the impact of his speech on the men and women she would soon lead. In her short twenty-two-year life, she’d heard a lot of fancy oratory. Another part of her listened to her commander’s words, felt them roll over her, into her. It had been a long time since mere words had raised the hackles on her neck, made her want to rip some bastard limb from limb.

“The civilians tried to get her back.” Kris measured his pause. He came in right on the downbeat. “They failed. Now they’ve called for the dogs.”

The marines around Kris growled for their skipper. She’d only worked with them for four days; the Typhoon had sortied on two hours’ notice! Captain Thorpe had gotten them away from space dock, short half the crew and without a marine lieutenant to command the drop platoon. Now a boot ensign named Longknife was surrounded by marines with three to twelve years in the Corps, champing at the bit to do something definite and dangerous.

“You’ve trained. You’ve sweated.” The captain’s words had the staccato of a machine gun. “You’ve drilled for this moment since you joined the Corps. You could rescue that kidnapped girl with your eyes closed.” In the dim light of the drop bay, eyes gleamed with inner fire. Jaws tensed; hands closed in tight fists. Kris glanced down; so were hers. Yes, these troops were ready, all except one boot ensign. Dear God, don’t let me screw up, Kris prayed silently.

“Now drop, Marines. Kick some terrorist butt, and put that little girl back in her mother’s arms where she belongs.”

“Ooh-rah,” came back from twelve hyped men and women as the captain slow marched for the exit. Well, eleven hyped marines and one scared ensign. Kris put the same angry confidence into her shout as she heard from the rest. Here was none of the calm, the cool of Father’s political speeches. Here was why Kris had joined the Navy. Here was something real; something she could get her hands on and make happen. Enough of endless talk and nothing done. She grinned. If you could see me now, Father. You said the Navy was a useless waste of time, Mother. Not today!

Kris took a deep breath as her platoon turned back to their preparations. The smell of armor, ammunition, oil, and honest human sweat gave her a rush. This was her mission and her squad, and she would see that one little girl got home safe and sound. This child would live.

As the memory of another child rose to fill her mind’s eye, Kris stomped on the thought. She dared not go there.

Captain Thorpe paused in his exit march right in front of her. Eye to eye, he leaned into her face. “Keep out of your head, Ensign,” he growled in a whisper. “Trust your gut. Trust your platoon and Gunny. They’re good. The commodore thinks you have what it takes, even if you are one of those Longknifes. Show me what you’ve got. Take those bastards down hard. But if you’re as empty as your old man, let Gunny know before you funk out on us, and he’ll finish the mission. And I’ll drop you back in your momma’s lap in time for the next debutantes’ ball.”

Kris stared back at him, her face frozen, her gut a throbbing knot. He’d been riding her since she came aboard, never happy with her, always picking at her. She would show him. “Yes, sir,” she shouted in his face.

Around her, the troops grinned, figuring the skipper had a few choice words for the boot ensign, none knowing just how choice. The captain snickered. A scowl or a snicker or a growl was all she’d ever seen on his face since coming aboard. Was there a different crinkle to his eyes, a new uptwist to his lips? He turned before she could read him better.

It wasn’t her fault Father had signed all Wardhaven’s legislation for the last eight years. She had nothing to do with her great-grandparents splashing the family name all over the history books. Let the captain try growing up in shadows like those. He’d be just as desperate as Kris was to make her own name, find her own place. That was why she joined the Navy.

With a shiver Kris tried to shake off the fear of failure. She turned to face her locker and tried again to adjust the standard-issue, size three battle spacesuit to fit. Six feet tall and too small everywhere else was her usual requirements for a suit. She’d never had a civilian suit that didn’t leave her plenty of room for her pet computer to conform around her shoulders and down her arms, but those suits weren’t semirigid plasta-steel a centimeter thick. Nelly, worth more than all the computers on the Typhoon and probably fifty times as capable, was a problem in battle armor. Marines were expected to be lean as well as mean; nothing extra was allowed anywhere. Kris tried slipping the main bulk of the computer down to her chest. She didn’t carry much there, and most marine males seemed to be a bit bulky in that spot. Resealing herself in, she rotated her shoulders, bent, then stooped. Yes, that worked. She put on the helmet, rotated it until she got a firm click. With the faceplate down, the suit was a bit warm, but she’d been hot before.

“Krissie, can I have an ice cream?” Eddy wheedled. It was a hot spring day on Wardhaven, and they’d run to the park, leaving Nanna well behind them.

Kris fumbled in her pocket. She was the big sister; she was expected to plan ahead now, just like big brother Honovi had done for her when she was just a little kid. Kris had enough coins for two ice creams. But Father insisted that planning ahead included making things last. “Not now,” Kris insisted. “Let’s go see the ducks.”

“But I want an ice cream now,” came in as much of a wail as an out-of-breath six-year-old could muster.

“Come on, Nanna’s almost here. Race you to the duck pond.” Which got Eddy’s feet moving even before Kris finished the challenge. She beat him, of course, but only by as much as a ten-year-old big sister should beat a six-year-old kid brother.

“Look, the swans are back.” Kris pointed at the four huge birds. So they walked along the pond, not too far behind the old man with the corn who always fed the birds. Kris was careful to keep Eddy from getting too near to the water. She must have done a good job because when Nanna finally caught up with them, she didn’t give Kris a lecture about how deep the pond was.

“I want an ice cream,” Eddy demanded again with the single-mindedness of his few years.

“I don’t have any money,” Nanna insisted.

“I do,” Kris put in proudly. She had planned ahead, just like Father said smart people should.

“Then you go buy the ice cream,” Nanna grumbled.

Kris skipped off, so sure she would be seeing them again that she didn’t even look back.

There was a tap at her shoulder. With a shiver, she turned to see a freckled face and raised her faceplate in time to be met with a “Need help, short fork?”

The drop bay was busy and noisy, and her shiver went unnoticed. She managed the cheery “No way, wooden spoon,” reply the infectious grin and challenge demanded. Ensign Tommy Li Chin Lien had been born to a family of Santa Maria asteroid miners. Rather than hang around that isolated world, he’d joined the Navy to see the galaxy, thereby greatly disappointing his folks and, per his great-grandmother, his ancestors.

At Officer Candidate School, they’d passed hours swapping stories about how their parents had stormed and ranted against their career choice. Kris was surprised by how fast they became friends, one from supersophisticated Wardhaven, the other that crazy blend of Irish and Chinese that so much of Santa Maria’s working class still held to.

Right now, Tommy waved his universal tester in Kris’s face. Raised in vacuum, he distrusted air and gravity and viewed mud-raised people like Kris as hopeless optimists, dependent on him for the proper paranoia toward space. Kris raised her left arm for Tommy to plug his black box into the battle suit she’d been issued. While he ran his checks, Kris worked with Nelly, running her personal computer through interface tests with the command net. Auntie Tru, now retired from her job as Wardhaven’s Info War Chief, had helped Kris with Nelly’s interface, as she’d done with most of Kris’s math and computer homework for as long as Kris could remember. Nelly lit up Kris’s heads-up display with every report or screen authorized to a boot ensign on a mission . . . and a few it was better the skipper did not know Kris had access to. Kris and Nelly finished about the same time Tommy detached his tester from Kris. She flipped up her faceplate.

“Your camouflage adjustment is about five nanoseconds below optimum, but it meets Navy standards,” Tommy grumbled. The Navy rarely met his expectations for perfection. “Your coolant system isn’t all that far into the green, either.”

“I’m more worried about my heater. It’s arctic tundra where I’m headed, haven’t you heard?” She grinned.

He refused to swallow his scowl for her attempt at a Santa Maria brogue. “And there’s a bad gasket in there somewhere.” They’d been over that one before; one of the battle suit’s jelly seals was a slow leaker, but every suit aboard had at least one bum seal. It was a bitter joke among the troops; good seals went to the civilian market, weak ones went to lowest-bid government contracts.

“I’m not working the asteroids, Tommy. I won’t be living in this suit for a month.” Kris gave the standard reply the procurement chiefs gave her father. The prime minister of Wardhaven always accepted it. But then, he didn’t do drop missions. Today, his daughter was. “I’ll only be in vacuum an hour, two at the most. Sequim’s atmosphere is good.”

“Mud hen,” Tommy answered in disgust.

“Space head,” Kris shot back, giving Tommy one of his own trademark grins, then turned to the Light Assault Craft that would be carrying her and her squad. It was the minimum vehicle that could get you from orbit to the deck, not much more than a heat shield that doubled as a wing and a flip-on top that was just there for stealth. Then again, Kris had raced in smaller skiffs. “This check out?” she asked, serious once more.

“Didn’t I test it four times?” Tommy grinned. “Didn’t it pass four times? Your humble servant will get you there.” Which only left Kris struggling to keep hold of her temper. The Navy trusted the marines to put their asses on the line, but not with the car keys. It would be Tommy’s job to fly the two LACs from the Typhoon in orbit to the ground, all except for two or three minutes when ionization took the two LACs out of radio touch—and they’d be on autopilot for that. All the while, Kris and her eleven marines were supposed to sit there dumb and bored. That was just one part of the approved plan she would like to change. But a boot ensign does not change plans that her skipper and his Gunny Sergeant like.

“Help me on with my kit,” she told Tommy. Along the bay, the platoon members were paired up, checking each other’s suits, loading them up with weapons and drop gear. Corporal Santo went down Gunny’s squad, Corporal Li checked Kris’s. Gunny would double-check them; then Kris would triple-check.

Kris’s load was a tad lighter than her teammates’ since Nelly weighed in at half of a standard-issue Navy personal computer while holding all the command, control, communications, and intelligence—C3I in military speak—that an ensign could ask for. Still, hanging from her armor or carefully stowed in her pack were rocket-propelled grenades of many flavors; six spare magazines for her M-6, half of them rounds of nonlethal intent, the others real ones; as well as water, first aid, and food. Marines never left home without lugging a ton of stuff. Fully loaded, again Kris rotated her shoulders, twisted her hips, checked the load if not for comfort at least for problems. She’d carried more backpacking through the Blue Mountains on Wardhaven during college vacations. Those carefree months of outdoor living was one of the reasons she was here.

Tommy eyed her as she did a deep knee squat and bounced back up. “You good for this?”

“Everything’s in place. Not too heavy.”

“You good for this business? Rescuing a kidnapped kid.” The grin was gone; she saw what the Santa Marian looked like serious.

“I’m good for this, Tom. I’m the best Navy small arms weapons qualifications on this boat. I’ve got the best Navy physical training scores, too. The skipper’s right. I’m the best he’s got. And Tommy, I want this.”

“Ensign Lien to the bridge,” came over the ship’s MC-1, ending any further questions. Tommy clapped her on the back. “The luck of the little people and God go with you,” he said as he headed for the hatch.

“No spare seat for Him in an LAC,” Kris shot back over her shoulder, another salvo in their long-running debate. But Kris was already trailing Gunny, rechecking the fall of gear, reverifying weapons loads. She finished a second behind him.

He went over her kit, and she went over his. He tightened one of her straps and growled, “You’ll do, ma’am.” She found nothing to modify on him; she hadn’t expected to. Gunny had practiced for this moment for sixteen years. That this was his first live-fire mission in all that time didn’t seem to bother him or Captain Thorpe.

“Let’s drop, team!” Kris called to her loaned platoon.

With a shout of “Ooh-rah” the two squads turned in unison to face opposite bulkheads and board their two Light Assault Crafts. Kris went down the line of her squad one more time, checking their restraining harnesses and the arrangement of their gear as they settled into their low seats in the LAC. All readouts showed green. Still, Kris gave each a good hard tug. That webbing was the only thing holding her troopers in. Satisfied, she settled her own rump onto the low composite seat in this minimum spacecraft and stretched her legs out ahead of her, careful to avoid the control pedals. The legs of the tech seated behind her surrounded her. Kris had once tried a toboggan. Mother had refused in horror when Kris asked to take a ride downhill. That toboggan was roomy compared to an LAC.

She rechecked to make sure her harness was firmly attached to the LAC’s narrow keel, checked again to make sure none of her gear was out of place, then pulled the canopy down and felt it click into place. Like so much of the LAC, the canopy was paper thin; it added nothing more than stealth to the craft. Only their drop suits would protect Kris and her troops from the vacuum of space or the heat of reentry.

The control stick began to rotate between Kris’s legs. That would be Tommy running tests. Still, the sight of it moving brought back good memories of some damn fine stick time of her own. She wiggled in her seat and felt the light craft respond to her movements. Bigger than a racing skiff but just as sweet.

Kris banished those distractions by replaying the drop plan in her mind as she waited. These kidnaping sons-a-bitches had a simple plan. They’d snapped up the Sequim General Manager’s sole child during a school outing, then dragged the poor kid off to the northern wilderness before anyone knew what had happened. Ignore the child’s name . . . much too familiar. Only pain there. Quickly Kris returned to tonight’s problem. The approaches to the

kidnappers’ hideout were long, difficult, dangerous—and booby-trapped! So far, the bad guys had outsmarted—and killed—too many good people.

Kris ground her teeth; how had cruds like these gotten their hands on some of the most sophisticated traps and countermeasures in human space? She could understand the traps; humans now frequented planets with very nasty critters. And while she had never hunted big game herself, she was looking forward to this hunt for the most dangerous game. What frosted her was the legal bunk used by specialty stores to excuse their sale of measures and countermeasures that were only going to make her job damn dangerous tonight. Normal people didn’t need electrocardiogram jammers. Why would any good citizen need a decoy device to simulate a human heat signature? Blast it, her suit was warm; sweat was already running down her back.

The day was so hot, the ice cream melted even as Kris trotted toward the duck pond. Kris paused just long enough to give both ice cream cones a quick lick, then felt guilty. “Eddy, I’ve got your ice cream,” she called as she hurried on. She hurried so much that she was well out of the trees and halfway across the vale to the pond before the wrongness of it got through to her. Kris came to a slow halt.

Eddy wasn’t there!

The man with the corn had fallen, half in the water. The ducks gathered around him to pluck at the fallen grain.

Two lumps of clothes doted the vale. In her nightmares that night, Kris would recognize them for agents who had been with her for years. But right then, her eyes were riveted on Nanna. She had fallen down. Her arms and legs splayed around like a rag doll. Even at ten, Kris knew that was all wrong for a real person.

Kris began to scream. She dropped her ice cream cones as she tried to cram her hands in her mouth, bite down hard on knuckles hoping the pain would wake her from this bad dream. Somewhere behind her, a voice shouted into a commlink. “Agents down. Agents down. Dandelion is nowhere in sight. I repeat, Dandelion is missing.”

A flashing red light grabbed Kris’s attention. “You did it again,” she growled at herself as she yanked her thoughts back to the problem at hand. Around her, the drop bay ran through decompression. Air gone, Kris and her troopers breathed only what their drop suits provided. Kris checked all her readouts. Her suit was good, as good as Navy issue got. So were all of her troopers. “Good to go,” she reported.

With a thump to Kris’s rear, the LAC fell into silent, black space. Tommy let them drift for only the moment it took Kris to get a good look at the Typhoon, her smart-metal hide stretched thin to give the crew individual rooms and spin gravity while in orbit. Her bow and stern was proudly painted with the blue and green flag of the Society of Humanity. Then the LAC came alive; the stick moved as Tommy guided both LACs into reentry.

Well, if Tommy was doing the work, Kris could use the time to check the ground situation once more. “Nelly, show me the real time target feed,” Kris subvocalized. The hunting lodge filled Kris’s heads-up display. Several dozen human shadows showed on the infrared detection. Six or eight moved around the building . . . all in pairs. Per the guarantee provided with every human heat decoy sold, there was no way Kris was supposed to know that only five real humans were moving. Thank God the manufacturers had so far stuck to the pledge of silence the government had extracted from them.

For ten years, no bad guys had tumbled to the fact that 98.6 degrees was only the average human temperature. This late at night most people’s body heat was slipping down into the 97s and 96s. In the six upstairs rooms of the lodge, the heat signatures of six little girls lay chained to their beds. Two gunmen sat at opposite ends of the hall, ready at the first sign of rescue to dash into the one room that held the kidnapped girl and kill her. Thanks to the sensors on the fifty-gram Stoolpigeon hovering 1,000 meters above the log cabin, Kris knew there was only one gunman—and which room held the terrified girl.

Terrified! Kris ground her teeth, then looked out of the LAC to rest her eyes on the planet revolving slowly below her. She tried to do anything but touch the nerve that took her again into her little brother’s grave. At least these kidnappers had not buried their victim under tons of manure with a damaged air pipe the only lifeline to the world for a six-year-old kid.

At school, Kris had overheard other students talking, saying that Eddy was dead hours before her parents paid the ransom. She didn’t know the truth of that. There were some reports she just couldn’t read, some media coverage she could never sit through.

What could never be ignored for a moment were the what-ifs. What if Kris hadn’t gone for ice cream? What if the bad guys had had to take down Nanna and Eddy and Kris? What would a wild ten-year-old girl have done to their plans?

Kris shook her head, willed away the images. Stay there too long, and tears came. A spacesuit was no place for tears.

Kris focused on the planet below. The day terminator lay ahead, changing the green and blue cloud-shrouded globe to dark—darkness and storms. A surprise night drop needed thunder to cover the sonic booms, darkness to hide their approach, night to make guards inattentive.

Kris smiled, remembering other planets she’d watched from orbit, a fast racing skiff under her. And her smile slid into a scowl as the memories she’d been struggling to hold at arm’s length for a week came flooding back.

Father vanished from Kris’s life the day after Eddy’s funeral. Off to the office before she awoke, he was rarely home before her bedtime.

Mother was something else. “You’ve been a little savage long enough. Time to make a proper young lady out of you.” That didn’t get Kris off the hook for winning soccer games for Father or showing up for his political parties. But Kris quickly discovered “proper young ladies” not only went to ballet but also accompanied Mother to teas. As the youngest at any tea by twenty years, Kris was bored silly. Then she noticed that some women’s teas smelled funny. It wasn’t long before Kris got a chance to taste them. They tasted funny, too . . . but they made Kris feel better, the parties go faster. It wasn’t long before Kris found what was being added to their tea . . . and how to raid her father’s liquor cabinet or mother’s wine closet.

Somehow, the drinking made the days endurable. Kris didn’t even care when her grades took a nosedive. It didn’t matter; Mother and Father only frowned. Other kids at school had fun things like skiff racing from orbit; Kris had her bottle. Of course, the bottle and the pills Mother’s doctor prescribed to help Kris be more ladylike did not help her soccer game. The coach shook his head and sidelined her as much as he could. Harvey, the chauffeur who took her to all the games, just seemed kind of sad.

But Harvey was grinning the afternoon he picked Kris up from school late. “Your dad’s invited your Great-grampa Trouble to dinner tonight. General Tordon is on Wardhaven for meetings,” Harvey added before she asked. Kris spent the drive home wondering what she’d say to someone straight out of her history books.

Mother was in a snit, overseeing dinner preparations herself and mumbling that legends should stay in the books where they belonged. Kris was sent upstairs to do homework, but she staked out the balcony, reading with one eye and watching the front door with the other. Kris wasn’t sure what to expect. Probably someone ancient, like old Ms. Bracket who taught history and seemed dry and wrinkled enough to have lived it. All of it!

Then Grampa Trouble walked through the front door. Tall and trim, gleaming in undress greens, he looked like he could destroy an Iteeche fleet just by scowling at them. Only he wasn’t scowling. The grin on his face was infectious; Mother was right, he was totally inappropriate for a “proper legend.” And at dinner, the stories he told. After dinner, Kris couldn’t remember a single one of them, at least not completely. But during supper they were all funny, even those that should have been horrifying. Somehow, no matter how bad the odds were or how impossible the situation had been, Grampa Trouble made it sound terribly funny. Even Mother laughed, despite herself. And when supper was over, Kris managed to dodge Mother until she excused herself for her whist club. Kris wanted to hang around this wondrous apparition forever. And when they were alone and he turned his full attention to Kris, she knew why kittens curled up in the sun.

“Your dad tells me you like soccer?” he said, settling into a chair.

“Yeah, pretty much,” Kris answered seating herself ladylike across from her grampa and feeling very grown-up.

“Your mom says you’re very good at ballet.”

“Yeah, pretty much.” Even at twelve, Kris knew she was not holding up her end of the conversation. But what could she say to someone like her grampa?

“I like orbital skiff racing. Ever do any racing?”

“Naw. Some kids at school do.” Kris tasted excitement. Then she remembered herself. “But Mother says it is much too dangerous. And nothing for a proper young lady.”

“That’s interesting,” Grampa Trouble said, leaning back in his chair and stretching his hands upward. “A girl won the junior championship for Savannah last year. She wasn’t much older than you.”

“She wasn’t!” Kris stared, wide-eyed. Even from Grampa, she couldn’t believe that.

“I’ve rented a skiff tomorrow. Want to take a few drops with me?”

Kris fidgeted in her chair. “Mother would never let me.”

Grampa brought his hands to rest on the table, only inches away from Kris’s. “Harvey tells me your mom usually sleeps in on Saturday. I could pick you up at six.” Later, Kris would realize that Grampa Trouble and the family chauffeur were in cahoots on this. But Kris had been too excited by the offer just then to put two and two together.

“Could you?” Kris yelped. She couldn’t remember the last time she’d been up early on her own. She also couldn’t remember the last time she’d done something that wasn’t on Mother or Father’s To-Do List. She couldn’t remember because to do that would be to remember what life was like with Eddy. “I’d love to,” she said.

“One thing,” Grampa Trouble said, reaching across the table to take her small, soft hands in his tanned, calloused ones. His touch was almost electric in its shock. His eyes looked into hers, stripping away the little girl that faked it for so many. Kris sat there, with nothing but herself to hang on to. “Your mother is right. Skiff racing can be dangerous. I only take people riding with me who are stone cold sober. That won’t be a problem for you, will it?”

Kris swallowed hard. She’d been laughing so hard at Grampa Trouble’s stories that she hadn’t stolen a drink at supper. She hadn’t had one since lunch at school. Could she go through the night? “It won’t be a problem,” Kris assured him.

And somehow she made it. It wasn’t easy; she woke up twice crying for Eddy. But she thought about Grampa and all the stories she had overheard from the school kids about how fun it was to see the stars above you and ride a falling star to Earth, and somehow Kris didn’t tiptoe downstairs to Father’s bar.

Kris made it through that night to stand at the top of the stairs and look down at Grampa Trouble so magnificent in his green uniform, waiting patiently for her on the black and white tiles of the foyer. Balanced careful as ever she did in ballet class, Kris went down the stairs, showing Grampa just how sober she was. His smile was a small, tight thing, not at all the open-faced one Father flashed all his political friends. Grampa’s tight little smile meant more to Kris than all she’d gotten from her father or mother.

Three hours later, Kris was suited up and strapped into the front seat of a skiff when Grampa Trouble hit the release and they dropped away from the space station. Oh, what a ride! Kris saw stars so close she could almost touch them. The temptation came to pop her belt, to drift away into the dark, to fall like

a shooting star and make whatever amends she could to dead little Eddy. But she couldn’t do that

to Grampa Trouble after all the trouble he’d gone through to get her here. And the beauty of the unblinking stars grabbed Kris, enveloping her in their cold, silent hug. The pure, lean curves of skiffs on reentry were mathematics in motion. She’d lost her heart . . . and maybe some of her survivor’s self-loathing.

Mother was actually pacing the foyer when they came in late that evening. “Where have you been?” was more an accusation than a question.

“Skiff racing,” Grampa Trouble answered as evenly as he told jokes.

“Skiff racing!” Mother shrieked.

“Honey,” Grampa Trouble said softly to Kris, “I think you better go to your room.”

“Grampa?” Kris started, but Harvey was taking Kris’s elbow.

“And don’t you come down before I send for you.” Mother enforced Grampa’s suggestion. “And what did you think you were doing with my daughter, General Tordon?” Mother said coldly, turning on Grampa.

But Grampa Trouble was already heading toward the great library. “I think it best we finish this conversation out of earshot of little pitchers with big ears,” he said with all the calm Mother lacked.

“Harvey, I don’t want to go to my room,” Kris argued as she and the chauffeur went up the stairs.

“It’s best you do, little friend,” he said. “Your mother’s been stretched quite a ways today. There’s nothing to be gained by you pushing her any further.”

Kris never saw Grampa Trouble again.

But a week later, Judith came into her life, a woman Grampa Trouble would probably have enjoyed meeting. Judith was a psychologist.

“I don’t need a shrink,” Kris told the woman flat out.

“Why’d you throw the soccer game last month?” Judith shot right back.

“I didn’t.” Kris mumbled.

“Your coach thinks you did. Your dad thinks so, too.”

“How would Father know?” Kris asked with all the sarcasm a twelve-year-old could muster.

“Harvey recorded the entire game,” Judith said.

“Oh.”

So they talked, and Kris found that Judith could be a friend. Like when Kris shared that she wanted to do more skiff racing, but Mother would have kittens at the very thought. Instead of agreeing with Mother, Judith asked Kris why Mother shouldn’t have a kitten or two? The thought of Mother with a kitten made Kris laugh, which needed an explanation, and before they were done, Kris had come to realize that what Mother wanted wasn’t always the best, and that the mother of a twelve-year-old girl should have kittens occasionally. Kris went on to win Wardhaven’s junior championship to the prime minister’s delight and Mother’s horror.

“Get out of your head,” Kris growled in Captain Thorpe’s voice and yanked tight on her restraining harness, a life-affirming act that now came naturally to her.

Then Kris’s stomach shot into her throat as her lander turned dervish, spinning to the right as the bottom dropped out from underneath her and the still-blasting thrusters rose above.

“What the hell?” “Who’s driving this bus?” rattled in her ears as Kris grabbed for the wildly gyrating control stick. Aft, Corporal Li restored discipline with a “Pipe down.”

The stick fought Kris, refusing to obey. She punched her commlink to the Typhoon. “Tommy, what the hell is going on?” Her words echoed empty in her helmet; her commlink was as dead as she and her crew would be if she didn’t do something—fast.

Mashing the manual override, Kris took command of her craft. With hardly a thought, her hands went though the motions needed to dampen down the spin and pitch. The LAC was heavier, slower to respond than a skiff. But Kris fought it . . . and it obeyed.

“That’s better,” came from one of the grateful marines behind her. Unless Kris figured out fast where they were and where they were going, this momentary “better” just meant they’d be less shook up when they burned on reentry.

“Nelly, I need skiff navigation, and I need it now.” In a blink, the familiar skiff routines took form on her heads-up. “Nelly, interrogate GPS system. Where am I?” The LAC became a dot on her heads-up, vector lines extended from it. She’d been accelerating rather than decelerating!

“Corporal, get a line-of-sight link to Gunny’s LAC.”

“I’ve been trying, ma’am, but I don’t know where he is.”

Her computer could probably tell Kris where the sergeant should be with respect to them, but Nelly was doing her best to plot a course that would win Kris another championship.

They didn’t hand out skiff trophies just for hitting that dinky ground target. They expected winners to do it in style: be on the dot, use less fuel, take less time. Kris gulped as her heads-up display filled with the harsh challenge ahead. The LAC was out of position and lower on fuel than any skiff she’d ever flown in competition. It would take every ounce of skill Kris had to land her marines anywhere within a hundred kilometers of one terrified little girl.

Kris had raced for trophies. Tightening her grip on the stick, she began a race for a little girl’s life.

Descriere

Wardhaven marine Kris Longknife has a lot to prove in the struggle between Earth and hundreds of warring colonies. But after an ill-conceived attack, Kris must choose between certain death or mutiny. Original.