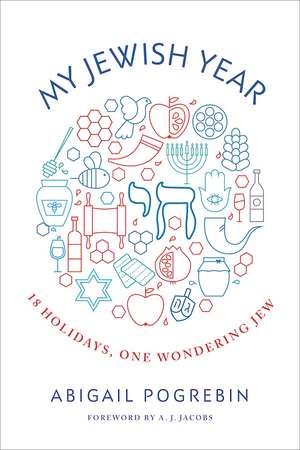

My Jewish Year: 18 Holidays, 1 Wondering Jew

Autor Abigail Pogrebin Cuvânt înainte de A. J. Jacobsen Limba Engleză Hardback – 14 mar 2017

In the tradition of The Year of Living Biblically by A.J. Jacobs and Walking the Bible: A Journey by Land Through the Five Books of Moses by Bruce Feiler comes Abigail Pogrebin’s My Jewish Year, a lively chronicle of the author’s journey into the spiritual heart of Judaism.

Although she grew up following some holiday rituals, Pogrebin realized how little she knew about their foundational purpose and contemporary relevance; she wanted to understand what had kept these holidays alive and vibrant, some for thousands of years. Her curiosity led her to embark on an entire year of intensive research, observation, and writing about the milestones on the religious calendar.

Whether in search of a roadmap for Jewish life or a challenging probe into the architecture of Jewish tradition, readers will be captivated, educated and inspired by Abigail Pogrebin’s My Jewish Year.

Although she grew up following some holiday rituals, Pogrebin realized how little she knew about their foundational purpose and contemporary relevance; she wanted to understand what had kept these holidays alive and vibrant, some for thousands of years. Her curiosity led her to embark on an entire year of intensive research, observation, and writing about the milestones on the religious calendar.

Whether in search of a roadmap for Jewish life or a challenging probe into the architecture of Jewish tradition, readers will be captivated, educated and inspired by Abigail Pogrebin’s My Jewish Year.

Preț: 136.68 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 205

Preț estimativ în valută:

26.15€ • 27.45$ • 21.71£

26.15€ • 27.45$ • 21.71£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 21 martie-04 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781941493205

ISBN-10: 1941493203

Pagini: 225

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 30 mm

Greutate: 0.61 kg

Editura: Fig Tree Books

Colecția Fig Tree Books

ISBN-10: 1941493203

Pagini: 225

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 30 mm

Greutate: 0.61 kg

Editura: Fig Tree Books

Colecția Fig Tree Books

Recenzii

Praise for My Jewish Year:

"To understand the Jewish calendar, Abigail Pogrebin immersed herself in its rhythms and rituals for a full twelve months. Her riveting account of this experience serves as a lively introduction to Judaism's holidays and fast days and opens a window on how Judaism is actually lived in 21st-century America." —Jonathan D. Sarna, University Professor and Joseph H. & Belle R. Braun Professor of American Jewish History, Brandeis University; author of American Judaism: A History

Praise for Stars of David:

“Consistently engaging....Pogrebin says this book grew out of her efforts to clarify her own Jewish identity. But you don't need to be on such a quest to enjoy the wide range of experiences and feelings recorded here.” —Publishers Weekly

“Pogrebin not only succeeded in securing access to dozens of celebrities, but also managed the difficult task of getting them to open up about a facet of their very public lives that generally has remained private.” —The Forward

“A great read.” —Women in Judaism

“A provocative and enjoyable book for Jews and gentiles alike.” —Library Journal

“Stars of David is an endearing book done with skill and taste.”—New York Post

“A fascinating book.” —The Charlotte Observer

Praise for One and the Same:

“Spot on. An honest explanation of how multiples feel about the relationship into which they were born.” —Newsweek

“An immensely satisfying, enlightening read.” —BookPage

“A fresh alternative to traditional how-to guidebooks for parents expecting two or more.” —Twins magazine

“This book about what it means to be a duplicate is smart and revealing and wise—and, well, singular.” —The Daily Beast

“Pogrebin’s candor about her own twinship [is] endearing. . . . A juicy read.” —Bookslut

"To understand the Jewish calendar, Abigail Pogrebin immersed herself in its rhythms and rituals for a full twelve months. Her riveting account of this experience serves as a lively introduction to Judaism's holidays and fast days and opens a window on how Judaism is actually lived in 21st-century America." —Jonathan D. Sarna, University Professor and Joseph H. & Belle R. Braun Professor of American Jewish History, Brandeis University; author of American Judaism: A History

Praise for Stars of David:

“Consistently engaging....Pogrebin says this book grew out of her efforts to clarify her own Jewish identity. But you don't need to be on such a quest to enjoy the wide range of experiences and feelings recorded here.” —Publishers Weekly

“Pogrebin not only succeeded in securing access to dozens of celebrities, but also managed the difficult task of getting them to open up about a facet of their very public lives that generally has remained private.” —The Forward

“A great read.” —Women in Judaism

“A provocative and enjoyable book for Jews and gentiles alike.” —Library Journal

“Stars of David is an endearing book done with skill and taste.”—New York Post

“A fascinating book.” —The Charlotte Observer

Praise for One and the Same:

“Spot on. An honest explanation of how multiples feel about the relationship into which they were born.” —Newsweek

“An immensely satisfying, enlightening read.” —BookPage

“A fresh alternative to traditional how-to guidebooks for parents expecting two or more.” —Twins magazine

“This book about what it means to be a duplicate is smart and revealing and wise—and, well, singular.” —The Daily Beast

“Pogrebin’s candor about her own twinship [is] endearing. . . . A juicy read.” —Bookslut

Notă biografică

Abigail Pogrebin's immersive exploration of the Jewish calendar began with her popular 12-month series for the Forward. Now, in My Jewish Year: 18 Holidays, One Wondering Jew, Pogrebin has expanded her investigation-infusing it with more of her personal story and exposing each ritual's deeper layers of meaning.

Pogrebin is also the author of Stars of David: Prominent Jews Talk About Being Jewish, in which she discussed Jewish identity with 62 celebrated public figures ranging from Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg to Steven Spielberg, from Mike Wallace to Natalie Portman. Pogrebin's second book, One and the Same, about the challenges of twinship, is grounded in her own experience as half of an identical pair. Most recently, she published "Showstopper," a bestselling Amazon Kindle Single that recalls her adventures as a 16-year-old cast member in the original Broadway production of Stephen Sondheim's flop-turned-cult-favorite, "Merrily We Roll Along."

Pogrebin's articles have appeared in Newsweek, New York magazine, The Daily Beast, Tablet, and many other publications. Pogrebin was formerly a producer for Ed Bradley and Mike Wallace at CBS News' 60 Minutes, where she was nominated for an Emmy. Before that, she produced for broadcasting pioneers Fred Friendly, Bill Moyers, and Charlie Rose at PBS.

A frequent speaker at synagogues and Jewish organizations around the country, Pogrebin has for seven years produced and moderated her own interview series at the JCC of Manhattan called "What Everyone's Talking About." Abigail Pogrebin lives in New York with her husband, David Shapiro, and their two teenage children.

A.J. Jacobs is the editor of What It Feels Like and the author of The Two Kings: Jesus and Elvis and America Off-Line. He is the senior editor of Esquire and has written for The New York Times, Entertainment Weekly, Glamour, New York magazine, New York Observer, and other publications. He lives in New York.

Pogrebin is also the author of Stars of David: Prominent Jews Talk About Being Jewish, in which she discussed Jewish identity with 62 celebrated public figures ranging from Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg to Steven Spielberg, from Mike Wallace to Natalie Portman. Pogrebin's second book, One and the Same, about the challenges of twinship, is grounded in her own experience as half of an identical pair. Most recently, she published "Showstopper," a bestselling Amazon Kindle Single that recalls her adventures as a 16-year-old cast member in the original Broadway production of Stephen Sondheim's flop-turned-cult-favorite, "Merrily We Roll Along."

Pogrebin's articles have appeared in Newsweek, New York magazine, The Daily Beast, Tablet, and many other publications. Pogrebin was formerly a producer for Ed Bradley and Mike Wallace at CBS News' 60 Minutes, where she was nominated for an Emmy. Before that, she produced for broadcasting pioneers Fred Friendly, Bill Moyers, and Charlie Rose at PBS.

A frequent speaker at synagogues and Jewish organizations around the country, Pogrebin has for seven years produced and moderated her own interview series at the JCC of Manhattan called "What Everyone's Talking About." Abigail Pogrebin lives in New York with her husband, David Shapiro, and their two teenage children.

A.J. Jacobs is the editor of What It Feels Like and the author of The Two Kings: Jesus and Elvis and America Off-Line. He is the senior editor of Esquire and has written for The New York Times, Entertainment Weekly, Glamour, New York magazine, New York Observer, and other publications. He lives in New York.

Extras

Chapter 1

Prepping Rosh Hashanah: Self-Flagellation in Summer

The instruction manual from the Israeli company that shipped my shofar (the trumpet made from a ram’s horn that’s blasted during the Jewish new year) says the blowing-technique can be learned by “filling your mouth with water.

You then make a small opening at the right side of your mouth, and blow out the water with a strong pressure. You must practice this again and again until you can blow the water about four feet away.”

Rosh Hashanah (literally “head of the year”) needs the shofar report to alert the world to the new year and to “wake us up” to introspection. This instrument is notoriously impossible to blow, especially with its prescribed cadence and strength; try it some time, it’s really hard. Synagogues troll for the brave souls who can actually pull it off without making the congregation cringe at sad attempts that emit tense toots or dying wails.

This year, I’m committed to fulfilling the commandment of hearing the shofar blast not only on the new year itself, but on every single morning of the 40 days of Elul, the weeks of self-examination that begin before Rosh Hashanah and end on Yom Kippur (the Day of Atonement).

So I’m standing at the kitchen sink, spewing tap water ineptly as my children look at me askance. My 17-year-old son, Ben, picks up the tawny horn. “Let me try.”

He kills it.

I hit on an idea. “I need you to be my blower every morning at dawn for the next 40 days.”

“Sure,” Ben answers blithely, despite the fact that he can’t be roused before 9 a.m. during the summer.

Before this project, I didn’t even know that the shofar gets blown daily for 40 days before the Jewish new year. (It’s actually fewer, because the horn can neither be honked on Shabbat nor the day before Rosh Hashanah.) Elul commemorates the 40 days when Moses went back up Mount Sinai to receive the second set of tablets. He smashed the first set in anger, after descending Sinai and discovering how his flock had doubted him and God, building a forbidden idol, a golden calf, to worship instead.

During this month of Elul, we ask forgiveness for that first, faithless idolatry and for our modern, countless missteps.

This is new to me: starting the path to repentance in August’s 80-degree weather. I’d previously thought that self-baring was a one-day affair—the Yom Kippur Cleanse. And that was plenty; twelve hours in synagogue without eating has always felt to me like penitence in and of itself. But now I’m learning a new rhythm. Contrition starts daily, 40 days before the mother-lode, incited every dawn by a noise one can’t ignore.

The first day, I opt for a loose definition of the word, “dawn,” which means waking when the sun is up already. It’s immediately obvious there’s no way I’m rousting Ben to blow the shofar for me. I’m on my own. I pick up the plastic trumpet and go into a room as far from my sleeping family as possible. I lift the horn to my mouth and try to follow the contradictory directions to both relax-and-purse the lips simultaneously, whistling air through the mouthpiece. To my shock, out comes a blast. It’s not pretty, but it’s hardy. I keep my gaze out the window, thinking how bizarre this is and at the same time, how meaningful. I blow one more time, a little tentatively because I don’t want to irk the house. The shofar sound is Judaism to me: raw, rousing, visceral, plaintive, insistent.

I then sit down on the sofa to Google the 27th Psalm on my iPhone because I learned we’re supposed to recite it aloud every morning of Elul for 40 days. This psalm is about God’s protection, which Elul reminds us we’re going to need during the upcoming days of judgment. I hear my voice saying the words and they’re oddly comforting, despite the dread.

"The Lord is my light and my salvation; whom should I fear? The Lord is the stronghold of my life; of whom shall I be afraid?

When evil-doers came upon me to eat up my flesh,

even mine adversaries and my foes, they stumbled and fell.

Though a host should encamp against me, my heart shall not fear;

though war should rise up against me, even then will I be confident.”

I then attempt the entire Psalm in Hebrew, and manage to get through it. Slowly. But I’m proud of the fact that I can.

When my kids wake up, they ask me how it went—my shofar right of passage. I tell them it felt interesting and dorky at the same time. Ben apologizes profusely for failing his assignment on the first day. I reassure him that I should be the one shouldering this ritual anyway; it’s my Wondering Year, my obligation.

As Elul accumulates and becomes routine, I find myself actually looking forward to the new morning regimen: wake up ahead of my husband, turn on the coffee machine, grab my plastic horn and face the window. My bleats are sometimes so solid they surprise me; but more often they’re shaky. I have to balance my desire to improve my blow-technique, against my fear of alienating the whole family.

Maimonides, the medieval philosopher, explained the custom of blowing shofar as “a wake-up call to sleepers, designed to rouse us from our complacency.” Am I complacent? About my behavior, my friendships, my parenting, my work? If complacency means, as the dictionary says, “a feeling of smug or uncritical satisfaction with oneself,” the answer is actually no. Just ask my therapist. I offer her a weekly catalogue of self-reproach.

But the fact is, I don’t scrutinize myself as comprehensively as I could when it comes to my character. Really, really candidly, what kind of person am I and how do I assess my private selfishness, pettiness, apathy? Can the peals of the shofar derail all our rationalizations?

Rabbi Irving (Yitz) Greenberg, author of one of the classic guides to the holidays, “The Jewish Way,” explains that Elul is a time for “accounting for the soul,” or cheshbon hanefesh, (a reckoning with one’s self).

Yitz, 82, a friend of my parents’ (which is why I can call him Yitz,) who is tall, slim, and somehow ethereal in his erudition, radiates the kind of placidity that makes me feel calm. Which is rare for me. If I could spend more time with Yitz, I’m convinced I’d be more Zen, not to mention, smarter.

“Just as the month before the summer is the time when Americans go on crash diets, fearing how their bodies will look on the beach,” he writes, “so Elul, the month before Rosh Hashanah, became the time when Jews went on crash spiritual regimens, fearing how their souls would look when they stood naked before God.”

I ask some other trusted rabbis how they’d suggest going about this “accounting for the soul.” They recommend choosing one trait a day and focusing introspection on that one quality. In an attempt to find a list of traits, I Google “Elul exercises” and “Elul practices” and come up with a list of middot (traits) that will take me through all 40 days. It’s an alphabetical litany of 40 characteristics suggested by a Toronto teacher named Modya Silver on his blog, which he has since taken down:

40 traits (middot) for each day of Elul:

• Abstinence – prishut

• Alacrity/Zeal – zerizut

• Arrogance – azut

• Anger – ka'as

• Awe of G-d – yirat hashem

• Compassion – rachamim

• Courage – ometz lev

• Cruelty – achzriut

• Decisiveness

• Envy – kina

• Equanimity – menuchat hanefesh

• Faith in G-d – Emunah

• Forgiveness – slicha

• Generosity – nedivut

• Gratitude – hoda'ah

• Greed Falsehood – sheker

• Hatred – sina

• Honour – k'vod

• Humility – anavut

• Joy – simcha – 20

• Laziness – atzlut

• Leadership – hanhagah

• Life force – chiyut

• Love – ahava

• Lovingkindness – chesed

• Miserliness – tza'yekanut

• Modesty – tzniut

• Order – seder

• Patience – savlanut

• Presence – hineni- 30

• Pride – Ga'ava

• Regret – charata

• Recognizing good – hakarat hatov

• Repentance – teshuva

• Respect

• Restraint – hitapkut

• Righteousness – tzedek

• Self-Awareness – hitlamdut

• Shame – busha

• Silence – shtika

• Simplicity – histapkut

• Slander – lashon hara

• Strength – gevurah

• Truth – emet

• Trust in G-d – bitachon

• Watchfulness – zehirut

• Wealth – osher

• Willingness – ratzon

• Worry – de'aga

• Fear/awe – yirah

I print out the list and think about who will attack it with me. My rabbi-guides told me to find a study partner (chevruta) to keep me on track and ensure a daily reckoning. So I need someone who’s going to be game and won’t balk at the discipline, let alone the candor.

My close friend, Dr. Catherine Birndorf, is a choice candidate: an accomplished psychiatrist and a fellow stumbling Jew, her bracing directness and humor keep me on my toes. Over our staple breakfast, soft-boiled eggs and toast, she relishes excavating our obsessions and roadblocks. She’s helped me through more false-alarm crises than I want to name.

I describe my proposal to her in our favorite diner, and Catherine doesn’t hesitate before saying yes, which makes me feel grateful because I didn’t really have a Plan B. It’s a lot to ask of someone—to do a penance-per-day—swapping confessions. Not everyone has the bandwidth.

Our agreed protocol is this: we’ll mull the trait-of-the-day during daylight hours, then at night, email each other frank reflections. To explain the purpose of this demanding Elul schedule, I send Yitz’s quote to Catherine—the one about “crash diets” in anticipation of the beach.

She writes back, “I'm a little skeptical of the beach analogy and crash dieting since it rarely leads to lasting change. But you gotta’ start somewhere...”

She’s right that vows don’t usually stick. I worry about that: breaking my promise this year to adhere to the holiday regimen, no matter how uncomfortable at times.

Rabbi Burt Visotzky, a jocund expert in Midrash (rabbinic commentary on Torah) who happens to be another family friend and has taught for three decades at the Jewish Theological Seminary, tells me that daily scrutiny is necessary to upend our complacency. “When you go to the therapist, you don’t just go once. You keep going. The repetition of Elul allows you to open yourself—not all at once— to things you’ve closed off.”

What have I closed off?

The realization that I still haven’t managed to turn compassion into action. I spent a semester teaching writing to formerly homeless men, but failed to find a way to stay in touch with them, let alone address the root causes.

I don’t see my parents enough.

My aunt and I haven’t recovered from a falling out four years ago.

I still look at my phone too much in restaurants, though I hate when others do that.

I tend to remind my son what he has to finish, instead of just asking how he is.

I see the point of Elul, the necessary runway to spiritual lift-off. How can one start the new year without looking fully—exhaustively—at the preceding one? When else do we permit ourselves, or demand of ourselves, a microscopic self-analysis?

I ask Burt—in his book-filled office—how he’d respond to those who say 40 days of navel-gazing is overkill before Yom Kippur.“You can’t walk into synagogue cold,” Burt fires back. “Let me use the shrink analogy again: You don’t just go into your therapy session without thinking ahead to what you want to discuss.” That’s true. The middot (40 traits for each day of Elul) force me to zero in on pockets of myself I rarely isolate.

Anger: I get riled when I feel something is unjust and I need to pause before writing the angry email.

Courage: I both have it and lack it, and wish I could have the courage to worry less about approval.

Cruelty: I don’t believe I am cruel, at least not consciously, and that’s a relief to acknowledge.

Forgiveness: I don’t forgive my own mistakes, no matter how slow, and I’m slow to forget friends’ affronts.

Prepping Rosh Hashanah: Self-Flagellation in Summer

The instruction manual from the Israeli company that shipped my shofar (the trumpet made from a ram’s horn that’s blasted during the Jewish new year) says the blowing-technique can be learned by “filling your mouth with water.

You then make a small opening at the right side of your mouth, and blow out the water with a strong pressure. You must practice this again and again until you can blow the water about four feet away.”

Rosh Hashanah (literally “head of the year”) needs the shofar report to alert the world to the new year and to “wake us up” to introspection. This instrument is notoriously impossible to blow, especially with its prescribed cadence and strength; try it some time, it’s really hard. Synagogues troll for the brave souls who can actually pull it off without making the congregation cringe at sad attempts that emit tense toots or dying wails.

This year, I’m committed to fulfilling the commandment of hearing the shofar blast not only on the new year itself, but on every single morning of the 40 days of Elul, the weeks of self-examination that begin before Rosh Hashanah and end on Yom Kippur (the Day of Atonement).

So I’m standing at the kitchen sink, spewing tap water ineptly as my children look at me askance. My 17-year-old son, Ben, picks up the tawny horn. “Let me try.”

He kills it.

I hit on an idea. “I need you to be my blower every morning at dawn for the next 40 days.”

“Sure,” Ben answers blithely, despite the fact that he can’t be roused before 9 a.m. during the summer.

Before this project, I didn’t even know that the shofar gets blown daily for 40 days before the Jewish new year. (It’s actually fewer, because the horn can neither be honked on Shabbat nor the day before Rosh Hashanah.) Elul commemorates the 40 days when Moses went back up Mount Sinai to receive the second set of tablets. He smashed the first set in anger, after descending Sinai and discovering how his flock had doubted him and God, building a forbidden idol, a golden calf, to worship instead.

During this month of Elul, we ask forgiveness for that first, faithless idolatry and for our modern, countless missteps.

This is new to me: starting the path to repentance in August’s 80-degree weather. I’d previously thought that self-baring was a one-day affair—the Yom Kippur Cleanse. And that was plenty; twelve hours in synagogue without eating has always felt to me like penitence in and of itself. But now I’m learning a new rhythm. Contrition starts daily, 40 days before the mother-lode, incited every dawn by a noise one can’t ignore.

The first day, I opt for a loose definition of the word, “dawn,” which means waking when the sun is up already. It’s immediately obvious there’s no way I’m rousting Ben to blow the shofar for me. I’m on my own. I pick up the plastic trumpet and go into a room as far from my sleeping family as possible. I lift the horn to my mouth and try to follow the contradictory directions to both relax-and-purse the lips simultaneously, whistling air through the mouthpiece. To my shock, out comes a blast. It’s not pretty, but it’s hardy. I keep my gaze out the window, thinking how bizarre this is and at the same time, how meaningful. I blow one more time, a little tentatively because I don’t want to irk the house. The shofar sound is Judaism to me: raw, rousing, visceral, plaintive, insistent.

I then sit down on the sofa to Google the 27th Psalm on my iPhone because I learned we’re supposed to recite it aloud every morning of Elul for 40 days. This psalm is about God’s protection, which Elul reminds us we’re going to need during the upcoming days of judgment. I hear my voice saying the words and they’re oddly comforting, despite the dread.

"The Lord is my light and my salvation; whom should I fear? The Lord is the stronghold of my life; of whom shall I be afraid?

When evil-doers came upon me to eat up my flesh,

even mine adversaries and my foes, they stumbled and fell.

Though a host should encamp against me, my heart shall not fear;

though war should rise up against me, even then will I be confident.”

I then attempt the entire Psalm in Hebrew, and manage to get through it. Slowly. But I’m proud of the fact that I can.

When my kids wake up, they ask me how it went—my shofar right of passage. I tell them it felt interesting and dorky at the same time. Ben apologizes profusely for failing his assignment on the first day. I reassure him that I should be the one shouldering this ritual anyway; it’s my Wondering Year, my obligation.

As Elul accumulates and becomes routine, I find myself actually looking forward to the new morning regimen: wake up ahead of my husband, turn on the coffee machine, grab my plastic horn and face the window. My bleats are sometimes so solid they surprise me; but more often they’re shaky. I have to balance my desire to improve my blow-technique, against my fear of alienating the whole family.

Maimonides, the medieval philosopher, explained the custom of blowing shofar as “a wake-up call to sleepers, designed to rouse us from our complacency.” Am I complacent? About my behavior, my friendships, my parenting, my work? If complacency means, as the dictionary says, “a feeling of smug or uncritical satisfaction with oneself,” the answer is actually no. Just ask my therapist. I offer her a weekly catalogue of self-reproach.

But the fact is, I don’t scrutinize myself as comprehensively as I could when it comes to my character. Really, really candidly, what kind of person am I and how do I assess my private selfishness, pettiness, apathy? Can the peals of the shofar derail all our rationalizations?

Rabbi Irving (Yitz) Greenberg, author of one of the classic guides to the holidays, “The Jewish Way,” explains that Elul is a time for “accounting for the soul,” or cheshbon hanefesh, (a reckoning with one’s self).

Yitz, 82, a friend of my parents’ (which is why I can call him Yitz,) who is tall, slim, and somehow ethereal in his erudition, radiates the kind of placidity that makes me feel calm. Which is rare for me. If I could spend more time with Yitz, I’m convinced I’d be more Zen, not to mention, smarter.

“Just as the month before the summer is the time when Americans go on crash diets, fearing how their bodies will look on the beach,” he writes, “so Elul, the month before Rosh Hashanah, became the time when Jews went on crash spiritual regimens, fearing how their souls would look when they stood naked before God.”

I ask some other trusted rabbis how they’d suggest going about this “accounting for the soul.” They recommend choosing one trait a day and focusing introspection on that one quality. In an attempt to find a list of traits, I Google “Elul exercises” and “Elul practices” and come up with a list of middot (traits) that will take me through all 40 days. It’s an alphabetical litany of 40 characteristics suggested by a Toronto teacher named Modya Silver on his blog, which he has since taken down:

40 traits (middot) for each day of Elul:

• Abstinence – prishut

• Alacrity/Zeal – zerizut

• Arrogance – azut

• Anger – ka'as

• Awe of G-d – yirat hashem

• Compassion – rachamim

• Courage – ometz lev

• Cruelty – achzriut

• Decisiveness

• Envy – kina

• Equanimity – menuchat hanefesh

• Faith in G-d – Emunah

• Forgiveness – slicha

• Generosity – nedivut

• Gratitude – hoda'ah

• Greed Falsehood – sheker

• Hatred – sina

• Honour – k'vod

• Humility – anavut

• Joy – simcha – 20

• Laziness – atzlut

• Leadership – hanhagah

• Life force – chiyut

• Love – ahava

• Lovingkindness – chesed

• Miserliness – tza'yekanut

• Modesty – tzniut

• Order – seder

• Patience – savlanut

• Presence – hineni- 30

• Pride – Ga'ava

• Regret – charata

• Recognizing good – hakarat hatov

• Repentance – teshuva

• Respect

• Restraint – hitapkut

• Righteousness – tzedek

• Self-Awareness – hitlamdut

• Shame – busha

• Silence – shtika

• Simplicity – histapkut

• Slander – lashon hara

• Strength – gevurah

• Truth – emet

• Trust in G-d – bitachon

• Watchfulness – zehirut

• Wealth – osher

• Willingness – ratzon

• Worry – de'aga

• Fear/awe – yirah

I print out the list and think about who will attack it with me. My rabbi-guides told me to find a study partner (chevruta) to keep me on track and ensure a daily reckoning. So I need someone who’s going to be game and won’t balk at the discipline, let alone the candor.

My close friend, Dr. Catherine Birndorf, is a choice candidate: an accomplished psychiatrist and a fellow stumbling Jew, her bracing directness and humor keep me on my toes. Over our staple breakfast, soft-boiled eggs and toast, she relishes excavating our obsessions and roadblocks. She’s helped me through more false-alarm crises than I want to name.

I describe my proposal to her in our favorite diner, and Catherine doesn’t hesitate before saying yes, which makes me feel grateful because I didn’t really have a Plan B. It’s a lot to ask of someone—to do a penance-per-day—swapping confessions. Not everyone has the bandwidth.

Our agreed protocol is this: we’ll mull the trait-of-the-day during daylight hours, then at night, email each other frank reflections. To explain the purpose of this demanding Elul schedule, I send Yitz’s quote to Catherine—the one about “crash diets” in anticipation of the beach.

She writes back, “I'm a little skeptical of the beach analogy and crash dieting since it rarely leads to lasting change. But you gotta’ start somewhere...”

She’s right that vows don’t usually stick. I worry about that: breaking my promise this year to adhere to the holiday regimen, no matter how uncomfortable at times.

Rabbi Burt Visotzky, a jocund expert in Midrash (rabbinic commentary on Torah) who happens to be another family friend and has taught for three decades at the Jewish Theological Seminary, tells me that daily scrutiny is necessary to upend our complacency. “When you go to the therapist, you don’t just go once. You keep going. The repetition of Elul allows you to open yourself—not all at once— to things you’ve closed off.”

What have I closed off?

The realization that I still haven’t managed to turn compassion into action. I spent a semester teaching writing to formerly homeless men, but failed to find a way to stay in touch with them, let alone address the root causes.

I don’t see my parents enough.

My aunt and I haven’t recovered from a falling out four years ago.

I still look at my phone too much in restaurants, though I hate when others do that.

I tend to remind my son what he has to finish, instead of just asking how he is.

I see the point of Elul, the necessary runway to spiritual lift-off. How can one start the new year without looking fully—exhaustively—at the preceding one? When else do we permit ourselves, or demand of ourselves, a microscopic self-analysis?

I ask Burt—in his book-filled office—how he’d respond to those who say 40 days of navel-gazing is overkill before Yom Kippur.“You can’t walk into synagogue cold,” Burt fires back. “Let me use the shrink analogy again: You don’t just go into your therapy session without thinking ahead to what you want to discuss.” That’s true. The middot (40 traits for each day of Elul) force me to zero in on pockets of myself I rarely isolate.

Anger: I get riled when I feel something is unjust and I need to pause before writing the angry email.

Courage: I both have it and lack it, and wish I could have the courage to worry less about approval.

Cruelty: I don’t believe I am cruel, at least not consciously, and that’s a relief to acknowledge.

Forgiveness: I don’t forgive my own mistakes, no matter how slow, and I’m slow to forget friends’ affronts.