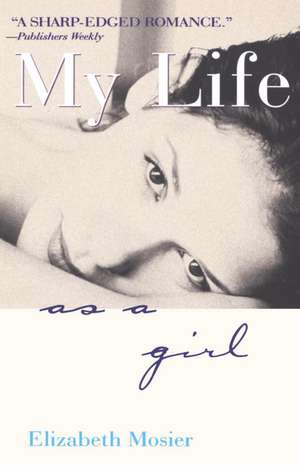

My Life as a Girl

Autor Elizabeth Mosieren Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 apr 2000 – vârsta de la 14 până la 17 ani

A whole country lies between where Jaime is -- Arizona -- and where she wants to be -- Bryn Mawr, a college for women in Pennsylvania. The jobs mean the difference between making a life for herself and being duped by a man, the way her mother was.

The plan is perfect -- until a boy named Buddy appears, reminding her of a character in the romantic stories her mother still loves to tell.

No one has to know about Buddy.

He's Jaime's secret.

Just for the summer.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 77.77 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 117

Preț estimativ în valută:

14.89€ • 15.35$ • 12.48£

14.89€ • 15.35$ • 12.48£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780375895227

ISBN-10: 0375895221

Pagini: 204

Dimensiuni: 214 x 146 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: Random House Books for Young Readers

ISBN-10: 0375895221

Pagini: 204

Dimensiuni: 214 x 146 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: Random House Books for Young Readers

Notă biografică

Elizabeth Mosier was raised in Arizona, the setting for My Life as a Girl and for her short stories, which have appeared in Sassy, Seventeen, The Philadelphia Enquirer Magazine, and various literary magazines. A graduate of Bryn Mawr College, she lives outside Philadelphia with her husband and two children, and directs Bryn Mawr's summer writing program for high school students. This is her first novel.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Chapter 3

"No way are you wearing a bunny getup and taking money from drunks," my best friend Rosa warned me when I circled the ad for COCKTAIL WAITRESS WANTED. I'd only tried the idea on as a dare --you had to be twenty-one, anyway, to serve -- but Rosa was serious. She snatched the newspaper away from me, rolled it up, and swatted me with it on the head. "You lose your clothes, girlfriend, you lose respect, too," she said. Rosa could afford to be uncompromising; she was guaranteed a summer job in her family's souvenir store downtown. The Gutierrez family took care of their own, while my dad took our savings to Vegas and left us to fend for ourselves.

It was the summer before Bryn Mawr, and my plan was to work two waitress jobs: one at The Phoenix, where a single night's tips would buy me Gray's Anatomy, and another at a greasy spoon. I'd take a day shift at the diner, a night shift at the pricey place, go back and forth between them. I thought I could pull it off.

I'd almost hooked the job at Ben Franklin's All-American Diner. I was smiling at the manager and leaning toward him, betting on his chubby face and straight, boyish bangs to make him behave, when he winked at me and said, "Under one condition."

I startled as if I'd been bit by a lapdog. It was early morning, and we were the only two people in the diner, alone in a vinyl booth, our knees nearly touching under the table. Though I hadn't wanted Mom to come with me to the interview, I was suddenly glad she was outside, waiting in her Pinto in the parking lot. I could see the car from where I was sitting, blue faded white from the Arizona sun. I hoped the manager could see it, too.

"What condition?" I asked, shifting my body toward the window.

"That you won't leave me in September," he said, setting my application aside. He had this dreamy smile on his face, and he was drawing voluptuous spirals on the steno pad he'd used to take notes. Glancing down, I saw him circle a word I hadn't noticed before: pretty.

Mom always told me I was lucky to be pretty, but Rosa had raised my consciousness. "Walk it like you talk it, if you want to go somewhere," she'd say.

"Listen, Mr. Thew," I said.

"Kenny," he corrected, tapping his nametag with his pen.

"Kenny," I said. I gripped the table's red-white-and-blue Formica rim to remind myself of the distance between us, space made for wideload truckers roaring in hungry off the Black Canyon Freeway. "What are you insinuating?" I asked, hoping the dirty-sounding word would make him back off.

But my accusation only dangled there between us, making me blush. Sure, I'd been flirting before, but couldn't he see I was just being polite?

Kenny leaned closer. "I know you college kids," he whispered as though we were conspirators.

"What do you know about us?" I asked, white-knuckling the table rim, ready to defend my morals.

He looked confused for a second and then said, "You're gone when summer's over, and I've got to hire all over again."

Oh, that," I said, relieved he wanted only loyalty, and not to fool around in the walk-in fridge. I let go of the table, let out my breath, and was surprised to find that behind my relief was a ready-made lie. "I'm deferring a year," I lied, looking down at my application, the line that said EDUCATION, where I'd proudly written Bryn Mawr. I was honest enough to be ashamed to meet his eyes, but corrupt enough to know he would take it as humility. "To work for tuition," I added. "My financial aid fell through."

"That's rough," he said, sounding really concerned.

"It's not the worst thing that could happen," I said, and right away I was superstitious for my scholarship, which paid tuition while I worked for room and board and book money. Losing it was the worst thing I could think of. I was counting on college to change my life. I tapped the table's underside, wincing as my fingers hit chewing gum instead of wood.

"Can't anybody help you?" Kenny asked. "Your parents?"

I shook my head. I didn't tell him Mom worked for minimum in the bakery at El Rancho, and Dad was indisposed in prison, awaiting his trial for embezzlement. What if Kenny had seen Dad's picture in the paper, the headline calling him CAPTURED CON?

For a second, Kenny's pen quit scratching on the page. "Boyfriend?" he asked, looking up from his steno pad and right at my collarbone.

I should have known.

I should have told him, Listen, Mister, I've got myself to rely on, and that's plenty. Whose grades, after all, got her into Bryn Mawr? That's what Rosa would have done. But if I'd learned one thing in eighteen years, it was how guys bow to the word boyfriend.

"He's saving up for an engagement ring," I said in an octave higher than my own, hardly believing what I heard myself say. There was no boyfriend, no promise of a ring. As Rosa would say, I wasn't going to college to get an M.R.S. It fooled Kenny, though. He coughed and said, "Okay. Gotcha. Loud and clear."

Then I worried the ploy had worked too well, that if I was already taken, Kenny would take back the job. I'm like my dad that way, can't walk away from the table when I'm winning. "In the meantime..." I said, rattling the ice cubes in my tea, "I'm staying in Phoenix."

That lie came as easily as a habit. It was the first line of a rap called "Worst Case Scenario," which Rosa and I used to say. I'm staying in Phoenix, one of us would start, and together we'd make up a miserable life: hitched to some loser guy right out of high school, cramped into a trailer in Happy Tepee RV Park, selling fry bread with beans at the mall, drinking beer at desert parties. The game kept us from griping about busting our brains to get into good colleges, and geared us up to face the thin rejection letters we were sure we'd find in our mailboxes. Until that afternoon in April, when the fat packages containing letters starting "We are pleased..." came to us from Stanford, Rosa's first choice, and from Bryn Mawr.

"Isn't Bryn Mawr near Philadelphia?" Kenny asked, and I nodded almost imperceptibly, watching for some sign that I'd gotten the job. He patted my arm, as though in a second I'd gone from conquest to old flame. Then, slowly, he folded my application into quarters and tucked it into his breast pocket.

I waited, afraid to breathe, like a gambler watching the dice roll.

"I'm from back east myself," he said finally, and then went on about how people are friendlier in Phoenix, the usual stuff back-Easters say to flatter you, for what seemed like an hour. I listened and smiled and told myself the job was just my safety; I'd make bigger bucks at The Phoenix. But the more Kenny made me wait for the job, the more I felt I had to have it. I was almost as anxious as I'd been at my Bryn Mawr interview.

By the time Kenny had finally finished hyping about the laid-back Western attitude, I'd blown the whole thing out of proportion. Suddenly, that job at Franklin's meant the difference between college or staying in Phoenix. Between my future as a doctor or being dependent on a man, like my mom. Between the M.D. degree I wanted and the M.R.S. that seemed a consolation prize.

"Can you start tomorrow morning?" Kenny asked.

"Yes!" I gushed, but then it was weird to have it decided. I felt more resigned to it than happy, the way my dad looked the time he won a pile at the greyhound races. That night he told me soberly, "You have to know your limit," as if winning were scientific and not just luck that could change in a minute, the way ours did.

Remembering Dad's words, I told myself I'd drawn the line, gone as far as I'd have to for a damn diner job.

Then Kenny said, "I'll go get your uniform."

"Army, navy, or marines?" I joked.

"I just love a girl in a uniform," he joked right back.

"Ha, ha," I said, tripping over the reprimand woman, which cowered at the tip of my tongue. That's what Bryn Mawr called its students, but in Arizona the line between one thing and another isn't so clear. I left it alone, but I was thinking: This summer's the end of my life as a girl.

"Size small?" he asked, trying not to look at my body.

"Medium," I said, straightening up in my seat.

"Read up on the rules while I'm gone."

Kenny left me alone then with a heavy notebook called "Franklin's Almanac." On the cover was the same cartoon that glared out from the floodlit highway sign: long-haired Ben with his square spectacles flying an electrified kite, and beneath it a corruption of Poor Richard's famous words: "Live to Eat." I flipped through the plastic pages, skipping company policy to look at greenish photos of Franklin's seafood specials, revived and deep-fried versions of what people got fresh in Philadelphia. I'd seen pictures of a place called the Italian Market, where iridescent fish were laid out on ice, and live crabs scrambled in buckets. But everything at Franklin's was hidden under greasy brown covers of breading, so you could hardly tell what it was.

I shut the rule book and looked around the diner, trying to picture myself hurrying out of the kitchen with a Kite 'n' Key Krab Kake Platter, trying to picture ninety hot summer days of the same. Someone had tried to make Franklin's look like Philly, with faux-brick floor tiles and lampshades shaped like Liberty Bells. On the walls were sun-faded posters of Independence Hall and the Delaware River, both much cleaner than seemed possible, and an outdated picture of downtown, missing the newer, mirrored buildings I'd seen in Bryn Mawr's viewbook. This inside information made me feel smug for a minute. But then, imagining how I'd describe the diner to Rosa, I felt embarrassed by how it was done up as if it wanted to be somewhere else.

We'd always planned to go to Stanford together, right up until last fall. Maybe I chose Bryn Mawr instead because an Eastern women's college was as far from familiar as I could get. Or because, for the first time in my life, I wanted to go somewhere without Rosa.

Kenny returned from the back with a frilly white Betsy Ross blouse draped over his arm. "Is that your mother out there in the car?" he asked.

"She didn't want to come in," I said, glancing out the window to make sure. I thought she was afraid she'd make the wrong impression, spoil my chance to land this prestigious job. She must have been feeling optimistic, though, because the car windows were closed and the air was on, an extravagance at seven A.M. The old Pinto was shaking like a piggy bank coughing out coins.

A string of tiny Liberty Bells hanging from the doorframe jangled a warning as Kenny leaned outside and waved her in. "Come in and have some iced tea," he called, and I was surprised when she did.

As Mom came into the diner, I stood by the booth like a guard dog, ridiculous because Franklin's --believe it -- was nothing you'd want to defend.

"Please excuse my uniform," she said, more to me than to Kenny, as she ran a hand across her hairnet like a spotlight calling attention to it. Her fingers were rainbow-stained with food color, and she had on her wedding band. Later in the day she'd remove it, complaining her fingers swelled from forcing cake icing through pastry tubes. The plastic badge on her chest bore her maiden name, Johnna Wynn, which she'd recently taken to using.

At home, Mom dressed like all the women in our old neighborhood, wrap-around skirts mail-ordered from Talbots, back east -- so she still looked strange to me in her uniform. But Kenny took in the bakery apron, the hairnet, and the stained fingers as though this was all there was to her. He'd fixed a smile on his face, like nothing she could say or do would surprise him. I thought how I'd give anything to keep a man from sizing me up that way.

But Mom just stood there in her uniform, a pretty-enough woman looking pleased to meet him. "I'll excuse your uniform," Kenny laughed, tugging on the sleeve of his short-sleeved dress shirt, a style people probably laughed at back east, "if you'll excuse mine."

Mom, of course, was charmed by this. "Nice place," she said as Kenny hustled away to pour her some tea, but she really meant nice man. I almost told her about the wet dreams this nice man had doodled on his steno pad, but by then I was doubting what I'd seen. I slumped back into my booth seat, which the air conditioning had turned clammy cold. Mom slid in beside me. "I bet you'll meet all kinds of neat people here," she said.

I scooted away a few inches. "You mean like truckers and drug runners?" I said, hating her persistent cheerfulness, the pioneer spirit I had always admired. No matter how bad things got, Mom still insisted we were lucky. And here I'd made up bad luck, the bit about the lost scholarship, to get a diner job. In Mom's book, a person couldn't go any lower than to trade pride for pity, and knowing that made me nasty. "Maybe we can start a book group," I said.

Mom said, "Remember you're lucky to get that fancy education."

She meant Bryn Mawr. I earned it, I wanted to shout at her, but my life was still mixed up with hers; I wasn't sure what was mine to claim. I only knew what had been taken from me, and what I wanted to leave behind.

We'd been rich, and then one day, after Dad's boss called him in to question receipts from a "business" trip to Vegas, we weren't. I kept thinking we'd get back on our feet again, even while Mom sent our family room furniture back "for repair," "lost" our better car, and moved us from our house to an apartment "for the time being." After Dad was arrested, she stopped the newspaper. All that time, I believed she was keeping us safe, putting some distance between us and disaster. Now I thought she'd been protecting herself.

"It will be good for Jaime to work with real people," Mom told Kenny as he set down a sweating glass of tea and took a seat across from us. "Before she heads off to the ivory tower."

"Ivory tower?" Kenny asked.

"Bryn Mawr," Mom said proudly.

Hearing that word, I snapped to attention; I'd almost forgotten the lie that got me the job. By then I was so far in that admitting to Kenny that I was going to Bryn Mawr seemed as awful as Mom catching me in a lie about it. I was scared Kenny would blow my cover. I felt like laughing out loud.

Kenny looked first at Mom, then at me. He opened his mouth and closed it, blinked at me once, and considered. "Who knows?" he said finally, clasping his hands behind his head and spreading his arms back, so his grinning face looked like a peacock's backed by its fan. "If Jaime's as good as she says she is, she might be my boss by the end of the summer."

"Who knows?" Mom laughed along, though she looked alarmed for a moment, picturing my career at the All-American Diner. Then Kenny winked at me so slightly it was almost a twitch, and it hit me that he thought he was protecting Mom from my bad news, the "lost" scholarship. When he handed me the Betsy Ross blouse and unfurled the skirt that lay beneath it, I knew he'd decided not to tell.

The skirt was the same faux-brick red as the floor and printed with white stars. It was cut as wide as a bell. I pictured my legs hanging from it, like a clapper.

"So chic," I said, trying to shrug off Kenny's complicity with sarcasm.

"Yes, very," Mom agreed.

You're staying in Phoenix, I could hear Rosa saying, and you're wearing a Liberty Bell.

Then Kenny said, "Of course, you'll have to hem it. Regulation is five inches above the knee."

"Above the knee?" I imagined my legs marked up like a ruler. The student I'd seen in the Bryn Mawr viewbook wore skirts hemmed between the knee and ankle, a dignified style with the quaint name "tea length." What Kenny was describing was more like beer length, a humiliating fashion that keeps coming back no matter how many women hate it.

"Regulations," he claimed.

Aha, I thought. I could hear Rosa saying, "How much are you going to compromise for two-o-one an hour plus tips?" I wondered myself.

Mom folded and pinched the material, frowning and clucking her tongue. "Five inches?" she asked, sounding uncertain. Surely she'd seen skirts that short in magazines, but those were made of tough denim or rich leather, not cheap muslin sprinkled with stars. On her face was the same blank expression I've used to shield myself on crowded city buses, not wanting to believe the hand that brushed my leg. I knew she was hoping he'd reassure her that his intentions were honorable, and I couldn't stand to watch her wait for it. "Is that really necessary?" she asked.

"It is at Franklin's All-American," Kenny laughed, turning to me. "Is that a problem?"

"No problem," I said, without thinking. I was always trying to sound bold, like Rosa, to hide my fear of being found out or left behind. But Kenny saw right through me. "Deal?" He offered his hand.

I gave Kenny the firm handshake I'd practiced with Rosa for college interviews, but his palm was moist and yielding; his fingers curved around mine. He held my hand just long enough for it to occur to me that it was too long. I looked up, expecting a sly wink, but instead his face was gentle.

If I'd known I'd spend the summer fending off Kenny's fatherly kindness, I might have walked. But by that point in the interview, I was tired of trying to guess his game. "Deal," I answered, feeling reckless, the way my dad must have felt during that last binge in Vegas, when he went over his limit and bet his whole life.

"That's my girl," Kenny said.

I could see by the way Mom kept her head down, pretending to examine the uniform, that she'd decided to give Kenny the benefit of the doubt. Not out of innocence or generosity, but out of the necessary stinginess that comes from having nothing left but pride. I'd always believed that her trust in my father was as blind as a daughter's. But as I watched her fold and refold the skirt's material, measuring out the required hemline, I noticed how cautiously and deliberately she moved.

Chapter Four

Even on the worst summer days, Rosa's house is always cool. While our brick apartment seems to beckon to the heat, sucking it in through the swamp cooler, the sun bounces off the Gutierrezes' adobe. Inside, the thick walls hold a family smell of meat cooking and cinnamon. I have always loved going there.

After my interview at the All-American Diner, I dropped Mom off at El Rancho and raced to Rosa's in the Pinto, pounding the scalding steering wheel impatiently, scowling into the nine o'clock sun. I parked at the curb and sprinted up the white-hot sidewalk path lined with prickly-pear cacti, toward the dark oak door. But before I could knock, Rosa's mother, Donna Gutierrez, pulled it open.

"¿Qué tal, Jaime?" she asked.

"Pretty good," I answered and ducked into the entryway. In the sudden shade of the room, my eyes ached and I squinted like a mole. Odd colors floated before me, the familiar symptom of retina burn. "¿Adónde va?" I managed as Mrs. Gutierrez came back into view from a cloud of green and yellow.

"I was just going to the store," she said.

"I thought you weren't open on Sundays," I said, disappointed to see that she was dressed for work, that by "store" she didn't mean the grocery, but La Piñata, the family business. The Gutierrezes usually had brunch together, after morning mass. While my parents recovered at home from Dad's night out at the greyhound races -- he in bed with an ice pack, Mom at the table with the bankbook -- I'd go to Rosa's and eat tortillas and eggs and spicy chorizo sausage.

But if there had been a feast here, it had already been eaten, the casseroles and dishes whisked out of sight. Mrs. Gutierrez was in a hurry, finger-combing her black broom of bangs, already halfway out the door.

"Our new mail-order business is really taking off," she answered, "and so Sunday's the only day I can do the books. Which reminds me..." She dug through her canvas bag and came up with a catalog. "I picked this up for your mother."

Our moms used to swap catalogs all the time -- their Sears and Spiegel for our Talbots and "Needless Markup" (Rosa's name for Nieman Marcus) -- but by then we had nothing left to trade. Mom had thrown away the few catalogs that kept coming since our credit cards were canceled, saying, "I can't believe all the trash in this world that's for sale."

But the catalog she handed me wasn't for dresses or even for La Piñata's turquoise rings and bola ties; it was an application for Arizona State. I took it uncertainly. Though she'd written Mom's name on the label, I was afraid it was intended for me.

"Good luck with your test," she said, meaning the SAT of waiting tables I was to take at The Phoenix that day. She kissed my cheek, then "Adios, Rosie," she called.

"Velouté?" Rosa quizzed me from her room at the end of the hall, and for a second, I thought she spoke Spanish. Then I remembered the French cooking terms she'd been helping me practice. I answered, "Velvet puree."

"íMuy bien!" Rosa said, and I could hear her sandals slap the terra cotta floor tiles as she went about her room getting dressed. She'd offered to come with me to The Phoenix if I'd drop her off afterward at Saguaro Hospital, where she volunteered two nights a week and Sundays in the children's ward. "I'm almost ready," she said. "Come on back."

But I lingered a moment in the family room, my favorite place in their house. The Gutierrezes didn't live rich, but everything they had was old and elegant, well used but somehow preserved. The red humpbacked couch had once belonged to Rosa's grandmother Isabel Nieto. I rubbed my palm on the plush upholstery that was faded and flattened in places, and touched the mahogany armrests, worn pale and glossy at their wrists. Beneath the couch was a woven wool rug, sand-colored and striped with black, that always shocked me if I dragged my feet across it. And everywhere -- sitting on window sills, resting atop the antique piano, hanging on the cream-colored walls -- were photographs of family, the three generations of Nietos and Gutierrezes who'd lived in the same house.

"Paupiette?" Rosa called out around a toothbrush, above the sound of water running in the bathroom sink.

"Little cup," I said, without missing a beat. To show off, I added, "As in hollowed-out cucumber filled with salmon mousse."

"Papillote?" she asked, trying to trick me with a term that sounded similar.

"Package," I said smugly. "As in fish steamed in a paper wrapper."

"Braggadocio," she said, and I'd begun to translate the term into something edible when it hit me it meant: smart aleck. The word had appeared on the SATs.

"Muchas gracias," I said.

I made my way down the hall slowly, admiring the series of silver-framed photos arranged in a line on the wall like a film strip. First, a view of the small orange grove the Nieto family had owned at Thirty-fifth Street, land that looked in 1930 like the end of the world. Then, pictures Rosa's grandfather Eduardo had taken, each a year apart, from the roof of the family's stucco-covered house. The photos showed the city creeping closer and closer, bringing houses and malls and ritzy mountain spas. Finally, they'd sold the orchard, bought a downtown storefront, and moved to the edge of a fancy neighborhood called Encanto Park.

Eventually, Rosa's mother married and brought her husband, Elias Gutierrez, home; that's where Rosa and her sister Christina were born. Nowadays, the neighbors enlivened their bungalows and Spanish colonials with turquoise and raspberry paint, but the Gutierrezes' house remained traditional mission white.

There was a photo of the whole family in front of the house: grandfather Eduardo, Donna and Elias, aunts and uncles and cousins up from Tucson, Christina and Tina's husband Tony, grandmother Nieto holding her namesake, baby Isabel. Behind them, the sagging arms of an old saguaro were draped with colored lights, and a sunburned plastic Santa stood guard by the door. The photo had been taken last Christmas, just before Dad's arrest.

Rosa came around the corner in her candy striper's uniform, twisting a tail of her long, mink-colored hair into a purple satin band. "I thought I'd find you here," she said, coming to stand beside me. I knew her family so well, had often wished they were my own.

I was looking at a photo of Tina's fifteenth birthday party, the quinceañara that Rosa had refused. In it, Tina wore a pink dress with a white sash and stood on the steps of St. Mary's, where her parents had once had to worship in the basement with others of Mexican descent. One of her white-gloved hands held a Bible, and the other shook the hand of the mayor, whose presence at the mass was recalled whenever the story was told.

Rosa had complained that the quinceañara was nonsense, more publicity for business than a celebration for her sister. Usually she scowled at the photo when she passed it, but today she blew dust off the cover glass and straightened the frame. Then she twirled in the peach aproned uniform she wore for her work at the hospital. "Here's my quinceañara dress," she said, laughing. "Much less expensive. Sweet, don't you think?"

"It's what all the candy stripers are wearing," I agreed.

"Ragout?" she quizzed me, wrapping an arm around my waist and pulling me to the front door.

"Gushy," I said, and winced as we stepped into the bright light outside.

"Gushy?" Rosa laughed, locking the door behind us. "I'd like to hear you say that to a customer."

"Whoops," I corrected myself. "I meant stewed."

* * * * *

"You should have seen the way he looked at me," I said, trying to rile Rosa about Kenny as we drove to The Phoenix. I wasn't testing Rosa so much as Kenny. I never knew what I could handle until Rosa checked it out.

But she wasn't having any of my complaints about Franklin's. "At least you're not cocktailing," she said, as she pretended to tune the awful AM radio and fussed with the inoperable air conditioning vent. "It's just one summer, Jaime. You'll be pouring tea for your calculus professor soon enough."

"And you'll be skipping class every time the surf's up," I kidded back. Rosa ignored me, pretending to be busy applying red lipstick in the sun visor mirror. "You missed the turn,"she said.

"It's at forty-eighth," I said.

"That was forty-eighth."

"Where's the church?" I asked, pulling into the left lane to make a U. "Wasn't there a church on that corner last week?"

"It's condos now," said Rosa.

Phoenix was disorienting that way; people and houses and businesses came and went so quickly, making a familiar landscape strange. Turning, I said, "It's a wonder the mountains don't get up and move."

Ahead, Camelback Mountain had always marked East and, for me, a new start. I would cross those mountains in August, I remembered with a rush of relief. Secretly I hoped that, when I came home for Christmas, Dad's trial would be over and his criminal record erased.

"Is this your uniform?" Rosa asked me, pulling the bell skirt from my backpack.

"I have to hem it five inches," I told her. "Practically to my navel."

"Five inches?" Rosa asked.

"That's the rule," I said.

Rosa unfurled the uniform and spread it across her lap. "Here's what you do," she said. She scrunched up the material, so the skirt looked even skimpier on her long legs than it would have on mine. "Follow the rule for the first week. Don't sew it, but fix it with tape. Then, little by little, let down the hem."

"That'll never work," I said.

"By the time this Kenny notices, he'll be so impressed with your work that he won't even care." Rosa pretended to tear the hem out, faking a juicy ripping sound.

"What if showing leg is my work?"

"Make him put it in your job description."

"Rosa!"

"Then quit and take my job at La Piñata."

"Take your job?" I asked, as surprised by her suggestion as I was by how much the idea appealed to me. Easy money, happy family -- I would have gladly traded her place for mine. "But you're doing so well," I said. "Your mom told me the mail-order business is really taking off."

"Oh, yes," said Rosa sarcastically. "We'll make sure no tourist leaves without a beaded fringe vest or an ashtray shaped like Arizona!"

"What's up with you, Rosa?"

"Nothing," she said, but that word was just the cork. It turned out her supervisor at Saguaro had asked her to help run a peer sex ed program for "high-risk" teens, a more polite word for kids from poor or violent or drug-dealing neighborhoods. Rosa had said "yes" immediately. But just that morning, her mother had said "no."

"Maybe she's afraid you'll learn something," I tried to joke.

"íQué lástima! I'm not a child!"

"Maybe she doesn't like the neighborhood," I suggested.

"The barrio, that's right," Rosa said, rolling her eyes. She unlocked her limbs, and flailed her arms in the air. "They want to pretend such poverty doesn't exist!"

"Maybe," I said. "But probably they just miss you already." I glanced at the A.S.U. application that lay on the dashboard, wondering if my mother was feeling the same thing.

Rosa didn't answer, but as we drove on, I saw her face soften and her hands refold neatly in her lap. It was the peacekeeping posture she'd put on for her parents ever since the letter came from Stanford, beckoning their last child away.

As I turned into the driveway for The Phoenix, the A.S.U. application tumbled to the floor. I bent to retrieve it, trying not to swerve. What was Mom up to? Was she hatching a plan to keep me home until Dad's trial? I tossed the application into the back seat, convinced that the lie I'd told that morning was turning into truth.

From the Hardcover edition.

"No way are you wearing a bunny getup and taking money from drunks," my best friend Rosa warned me when I circled the ad for COCKTAIL WAITRESS WANTED. I'd only tried the idea on as a dare --you had to be twenty-one, anyway, to serve -- but Rosa was serious. She snatched the newspaper away from me, rolled it up, and swatted me with it on the head. "You lose your clothes, girlfriend, you lose respect, too," she said. Rosa could afford to be uncompromising; she was guaranteed a summer job in her family's souvenir store downtown. The Gutierrez family took care of their own, while my dad took our savings to Vegas and left us to fend for ourselves.

It was the summer before Bryn Mawr, and my plan was to work two waitress jobs: one at The Phoenix, where a single night's tips would buy me Gray's Anatomy, and another at a greasy spoon. I'd take a day shift at the diner, a night shift at the pricey place, go back and forth between them. I thought I could pull it off.

I'd almost hooked the job at Ben Franklin's All-American Diner. I was smiling at the manager and leaning toward him, betting on his chubby face and straight, boyish bangs to make him behave, when he winked at me and said, "Under one condition."

I startled as if I'd been bit by a lapdog. It was early morning, and we were the only two people in the diner, alone in a vinyl booth, our knees nearly touching under the table. Though I hadn't wanted Mom to come with me to the interview, I was suddenly glad she was outside, waiting in her Pinto in the parking lot. I could see the car from where I was sitting, blue faded white from the Arizona sun. I hoped the manager could see it, too.

"What condition?" I asked, shifting my body toward the window.

"That you won't leave me in September," he said, setting my application aside. He had this dreamy smile on his face, and he was drawing voluptuous spirals on the steno pad he'd used to take notes. Glancing down, I saw him circle a word I hadn't noticed before: pretty.

Mom always told me I was lucky to be pretty, but Rosa had raised my consciousness. "Walk it like you talk it, if you want to go somewhere," she'd say.

"Listen, Mr. Thew," I said.

"Kenny," he corrected, tapping his nametag with his pen.

"Kenny," I said. I gripped the table's red-white-and-blue Formica rim to remind myself of the distance between us, space made for wideload truckers roaring in hungry off the Black Canyon Freeway. "What are you insinuating?" I asked, hoping the dirty-sounding word would make him back off.

But my accusation only dangled there between us, making me blush. Sure, I'd been flirting before, but couldn't he see I was just being polite?

Kenny leaned closer. "I know you college kids," he whispered as though we were conspirators.

"What do you know about us?" I asked, white-knuckling the table rim, ready to defend my morals.

He looked confused for a second and then said, "You're gone when summer's over, and I've got to hire all over again."

Oh, that," I said, relieved he wanted only loyalty, and not to fool around in the walk-in fridge. I let go of the table, let out my breath, and was surprised to find that behind my relief was a ready-made lie. "I'm deferring a year," I lied, looking down at my application, the line that said EDUCATION, where I'd proudly written Bryn Mawr. I was honest enough to be ashamed to meet his eyes, but corrupt enough to know he would take it as humility. "To work for tuition," I added. "My financial aid fell through."

"That's rough," he said, sounding really concerned.

"It's not the worst thing that could happen," I said, and right away I was superstitious for my scholarship, which paid tuition while I worked for room and board and book money. Losing it was the worst thing I could think of. I was counting on college to change my life. I tapped the table's underside, wincing as my fingers hit chewing gum instead of wood.

"Can't anybody help you?" Kenny asked. "Your parents?"

I shook my head. I didn't tell him Mom worked for minimum in the bakery at El Rancho, and Dad was indisposed in prison, awaiting his trial for embezzlement. What if Kenny had seen Dad's picture in the paper, the headline calling him CAPTURED CON?

For a second, Kenny's pen quit scratching on the page. "Boyfriend?" he asked, looking up from his steno pad and right at my collarbone.

I should have known.

I should have told him, Listen, Mister, I've got myself to rely on, and that's plenty. Whose grades, after all, got her into Bryn Mawr? That's what Rosa would have done. But if I'd learned one thing in eighteen years, it was how guys bow to the word boyfriend.

"He's saving up for an engagement ring," I said in an octave higher than my own, hardly believing what I heard myself say. There was no boyfriend, no promise of a ring. As Rosa would say, I wasn't going to college to get an M.R.S. It fooled Kenny, though. He coughed and said, "Okay. Gotcha. Loud and clear."

Then I worried the ploy had worked too well, that if I was already taken, Kenny would take back the job. I'm like my dad that way, can't walk away from the table when I'm winning. "In the meantime..." I said, rattling the ice cubes in my tea, "I'm staying in Phoenix."

That lie came as easily as a habit. It was the first line of a rap called "Worst Case Scenario," which Rosa and I used to say. I'm staying in Phoenix, one of us would start, and together we'd make up a miserable life: hitched to some loser guy right out of high school, cramped into a trailer in Happy Tepee RV Park, selling fry bread with beans at the mall, drinking beer at desert parties. The game kept us from griping about busting our brains to get into good colleges, and geared us up to face the thin rejection letters we were sure we'd find in our mailboxes. Until that afternoon in April, when the fat packages containing letters starting "We are pleased..." came to us from Stanford, Rosa's first choice, and from Bryn Mawr.

"Isn't Bryn Mawr near Philadelphia?" Kenny asked, and I nodded almost imperceptibly, watching for some sign that I'd gotten the job. He patted my arm, as though in a second I'd gone from conquest to old flame. Then, slowly, he folded my application into quarters and tucked it into his breast pocket.

I waited, afraid to breathe, like a gambler watching the dice roll.

"I'm from back east myself," he said finally, and then went on about how people are friendlier in Phoenix, the usual stuff back-Easters say to flatter you, for what seemed like an hour. I listened and smiled and told myself the job was just my safety; I'd make bigger bucks at The Phoenix. But the more Kenny made me wait for the job, the more I felt I had to have it. I was almost as anxious as I'd been at my Bryn Mawr interview.

By the time Kenny had finally finished hyping about the laid-back Western attitude, I'd blown the whole thing out of proportion. Suddenly, that job at Franklin's meant the difference between college or staying in Phoenix. Between my future as a doctor or being dependent on a man, like my mom. Between the M.D. degree I wanted and the M.R.S. that seemed a consolation prize.

"Can you start tomorrow morning?" Kenny asked.

"Yes!" I gushed, but then it was weird to have it decided. I felt more resigned to it than happy, the way my dad looked the time he won a pile at the greyhound races. That night he told me soberly, "You have to know your limit," as if winning were scientific and not just luck that could change in a minute, the way ours did.

Remembering Dad's words, I told myself I'd drawn the line, gone as far as I'd have to for a damn diner job.

Then Kenny said, "I'll go get your uniform."

"Army, navy, or marines?" I joked.

"I just love a girl in a uniform," he joked right back.

"Ha, ha," I said, tripping over the reprimand woman, which cowered at the tip of my tongue. That's what Bryn Mawr called its students, but in Arizona the line between one thing and another isn't so clear. I left it alone, but I was thinking: This summer's the end of my life as a girl.

"Size small?" he asked, trying not to look at my body.

"Medium," I said, straightening up in my seat.

"Read up on the rules while I'm gone."

Kenny left me alone then with a heavy notebook called "Franklin's Almanac." On the cover was the same cartoon that glared out from the floodlit highway sign: long-haired Ben with his square spectacles flying an electrified kite, and beneath it a corruption of Poor Richard's famous words: "Live to Eat." I flipped through the plastic pages, skipping company policy to look at greenish photos of Franklin's seafood specials, revived and deep-fried versions of what people got fresh in Philadelphia. I'd seen pictures of a place called the Italian Market, where iridescent fish were laid out on ice, and live crabs scrambled in buckets. But everything at Franklin's was hidden under greasy brown covers of breading, so you could hardly tell what it was.

I shut the rule book and looked around the diner, trying to picture myself hurrying out of the kitchen with a Kite 'n' Key Krab Kake Platter, trying to picture ninety hot summer days of the same. Someone had tried to make Franklin's look like Philly, with faux-brick floor tiles and lampshades shaped like Liberty Bells. On the walls were sun-faded posters of Independence Hall and the Delaware River, both much cleaner than seemed possible, and an outdated picture of downtown, missing the newer, mirrored buildings I'd seen in Bryn Mawr's viewbook. This inside information made me feel smug for a minute. But then, imagining how I'd describe the diner to Rosa, I felt embarrassed by how it was done up as if it wanted to be somewhere else.

We'd always planned to go to Stanford together, right up until last fall. Maybe I chose Bryn Mawr instead because an Eastern women's college was as far from familiar as I could get. Or because, for the first time in my life, I wanted to go somewhere without Rosa.

Kenny returned from the back with a frilly white Betsy Ross blouse draped over his arm. "Is that your mother out there in the car?" he asked.

"She didn't want to come in," I said, glancing out the window to make sure. I thought she was afraid she'd make the wrong impression, spoil my chance to land this prestigious job. She must have been feeling optimistic, though, because the car windows were closed and the air was on, an extravagance at seven A.M. The old Pinto was shaking like a piggy bank coughing out coins.

A string of tiny Liberty Bells hanging from the doorframe jangled a warning as Kenny leaned outside and waved her in. "Come in and have some iced tea," he called, and I was surprised when she did.

As Mom came into the diner, I stood by the booth like a guard dog, ridiculous because Franklin's --believe it -- was nothing you'd want to defend.

"Please excuse my uniform," she said, more to me than to Kenny, as she ran a hand across her hairnet like a spotlight calling attention to it. Her fingers were rainbow-stained with food color, and she had on her wedding band. Later in the day she'd remove it, complaining her fingers swelled from forcing cake icing through pastry tubes. The plastic badge on her chest bore her maiden name, Johnna Wynn, which she'd recently taken to using.

At home, Mom dressed like all the women in our old neighborhood, wrap-around skirts mail-ordered from Talbots, back east -- so she still looked strange to me in her uniform. But Kenny took in the bakery apron, the hairnet, and the stained fingers as though this was all there was to her. He'd fixed a smile on his face, like nothing she could say or do would surprise him. I thought how I'd give anything to keep a man from sizing me up that way.

But Mom just stood there in her uniform, a pretty-enough woman looking pleased to meet him. "I'll excuse your uniform," Kenny laughed, tugging on the sleeve of his short-sleeved dress shirt, a style people probably laughed at back east, "if you'll excuse mine."

Mom, of course, was charmed by this. "Nice place," she said as Kenny hustled away to pour her some tea, but she really meant nice man. I almost told her about the wet dreams this nice man had doodled on his steno pad, but by then I was doubting what I'd seen. I slumped back into my booth seat, which the air conditioning had turned clammy cold. Mom slid in beside me. "I bet you'll meet all kinds of neat people here," she said.

I scooted away a few inches. "You mean like truckers and drug runners?" I said, hating her persistent cheerfulness, the pioneer spirit I had always admired. No matter how bad things got, Mom still insisted we were lucky. And here I'd made up bad luck, the bit about the lost scholarship, to get a diner job. In Mom's book, a person couldn't go any lower than to trade pride for pity, and knowing that made me nasty. "Maybe we can start a book group," I said.

Mom said, "Remember you're lucky to get that fancy education."

She meant Bryn Mawr. I earned it, I wanted to shout at her, but my life was still mixed up with hers; I wasn't sure what was mine to claim. I only knew what had been taken from me, and what I wanted to leave behind.

We'd been rich, and then one day, after Dad's boss called him in to question receipts from a "business" trip to Vegas, we weren't. I kept thinking we'd get back on our feet again, even while Mom sent our family room furniture back "for repair," "lost" our better car, and moved us from our house to an apartment "for the time being." After Dad was arrested, she stopped the newspaper. All that time, I believed she was keeping us safe, putting some distance between us and disaster. Now I thought she'd been protecting herself.

"It will be good for Jaime to work with real people," Mom told Kenny as he set down a sweating glass of tea and took a seat across from us. "Before she heads off to the ivory tower."

"Ivory tower?" Kenny asked.

"Bryn Mawr," Mom said proudly.

Hearing that word, I snapped to attention; I'd almost forgotten the lie that got me the job. By then I was so far in that admitting to Kenny that I was going to Bryn Mawr seemed as awful as Mom catching me in a lie about it. I was scared Kenny would blow my cover. I felt like laughing out loud.

Kenny looked first at Mom, then at me. He opened his mouth and closed it, blinked at me once, and considered. "Who knows?" he said finally, clasping his hands behind his head and spreading his arms back, so his grinning face looked like a peacock's backed by its fan. "If Jaime's as good as she says she is, she might be my boss by the end of the summer."

"Who knows?" Mom laughed along, though she looked alarmed for a moment, picturing my career at the All-American Diner. Then Kenny winked at me so slightly it was almost a twitch, and it hit me that he thought he was protecting Mom from my bad news, the "lost" scholarship. When he handed me the Betsy Ross blouse and unfurled the skirt that lay beneath it, I knew he'd decided not to tell.

The skirt was the same faux-brick red as the floor and printed with white stars. It was cut as wide as a bell. I pictured my legs hanging from it, like a clapper.

"So chic," I said, trying to shrug off Kenny's complicity with sarcasm.

"Yes, very," Mom agreed.

You're staying in Phoenix, I could hear Rosa saying, and you're wearing a Liberty Bell.

Then Kenny said, "Of course, you'll have to hem it. Regulation is five inches above the knee."

"Above the knee?" I imagined my legs marked up like a ruler. The student I'd seen in the Bryn Mawr viewbook wore skirts hemmed between the knee and ankle, a dignified style with the quaint name "tea length." What Kenny was describing was more like beer length, a humiliating fashion that keeps coming back no matter how many women hate it.

"Regulations," he claimed.

Aha, I thought. I could hear Rosa saying, "How much are you going to compromise for two-o-one an hour plus tips?" I wondered myself.

Mom folded and pinched the material, frowning and clucking her tongue. "Five inches?" she asked, sounding uncertain. Surely she'd seen skirts that short in magazines, but those were made of tough denim or rich leather, not cheap muslin sprinkled with stars. On her face was the same blank expression I've used to shield myself on crowded city buses, not wanting to believe the hand that brushed my leg. I knew she was hoping he'd reassure her that his intentions were honorable, and I couldn't stand to watch her wait for it. "Is that really necessary?" she asked.

"It is at Franklin's All-American," Kenny laughed, turning to me. "Is that a problem?"

"No problem," I said, without thinking. I was always trying to sound bold, like Rosa, to hide my fear of being found out or left behind. But Kenny saw right through me. "Deal?" He offered his hand.

I gave Kenny the firm handshake I'd practiced with Rosa for college interviews, but his palm was moist and yielding; his fingers curved around mine. He held my hand just long enough for it to occur to me that it was too long. I looked up, expecting a sly wink, but instead his face was gentle.

If I'd known I'd spend the summer fending off Kenny's fatherly kindness, I might have walked. But by that point in the interview, I was tired of trying to guess his game. "Deal," I answered, feeling reckless, the way my dad must have felt during that last binge in Vegas, when he went over his limit and bet his whole life.

"That's my girl," Kenny said.

I could see by the way Mom kept her head down, pretending to examine the uniform, that she'd decided to give Kenny the benefit of the doubt. Not out of innocence or generosity, but out of the necessary stinginess that comes from having nothing left but pride. I'd always believed that her trust in my father was as blind as a daughter's. But as I watched her fold and refold the skirt's material, measuring out the required hemline, I noticed how cautiously and deliberately she moved.

Chapter Four

Even on the worst summer days, Rosa's house is always cool. While our brick apartment seems to beckon to the heat, sucking it in through the swamp cooler, the sun bounces off the Gutierrezes' adobe. Inside, the thick walls hold a family smell of meat cooking and cinnamon. I have always loved going there.

After my interview at the All-American Diner, I dropped Mom off at El Rancho and raced to Rosa's in the Pinto, pounding the scalding steering wheel impatiently, scowling into the nine o'clock sun. I parked at the curb and sprinted up the white-hot sidewalk path lined with prickly-pear cacti, toward the dark oak door. But before I could knock, Rosa's mother, Donna Gutierrez, pulled it open.

"¿Qué tal, Jaime?" she asked.

"Pretty good," I answered and ducked into the entryway. In the sudden shade of the room, my eyes ached and I squinted like a mole. Odd colors floated before me, the familiar symptom of retina burn. "¿Adónde va?" I managed as Mrs. Gutierrez came back into view from a cloud of green and yellow.

"I was just going to the store," she said.

"I thought you weren't open on Sundays," I said, disappointed to see that she was dressed for work, that by "store" she didn't mean the grocery, but La Piñata, the family business. The Gutierrezes usually had brunch together, after morning mass. While my parents recovered at home from Dad's night out at the greyhound races -- he in bed with an ice pack, Mom at the table with the bankbook -- I'd go to Rosa's and eat tortillas and eggs and spicy chorizo sausage.

But if there had been a feast here, it had already been eaten, the casseroles and dishes whisked out of sight. Mrs. Gutierrez was in a hurry, finger-combing her black broom of bangs, already halfway out the door.

"Our new mail-order business is really taking off," she answered, "and so Sunday's the only day I can do the books. Which reminds me..." She dug through her canvas bag and came up with a catalog. "I picked this up for your mother."

Our moms used to swap catalogs all the time -- their Sears and Spiegel for our Talbots and "Needless Markup" (Rosa's name for Nieman Marcus) -- but by then we had nothing left to trade. Mom had thrown away the few catalogs that kept coming since our credit cards were canceled, saying, "I can't believe all the trash in this world that's for sale."

But the catalog she handed me wasn't for dresses or even for La Piñata's turquoise rings and bola ties; it was an application for Arizona State. I took it uncertainly. Though she'd written Mom's name on the label, I was afraid it was intended for me.

"Good luck with your test," she said, meaning the SAT of waiting tables I was to take at The Phoenix that day. She kissed my cheek, then "Adios, Rosie," she called.

"Velouté?" Rosa quizzed me from her room at the end of the hall, and for a second, I thought she spoke Spanish. Then I remembered the French cooking terms she'd been helping me practice. I answered, "Velvet puree."

"íMuy bien!" Rosa said, and I could hear her sandals slap the terra cotta floor tiles as she went about her room getting dressed. She'd offered to come with me to The Phoenix if I'd drop her off afterward at Saguaro Hospital, where she volunteered two nights a week and Sundays in the children's ward. "I'm almost ready," she said. "Come on back."

But I lingered a moment in the family room, my favorite place in their house. The Gutierrezes didn't live rich, but everything they had was old and elegant, well used but somehow preserved. The red humpbacked couch had once belonged to Rosa's grandmother Isabel Nieto. I rubbed my palm on the plush upholstery that was faded and flattened in places, and touched the mahogany armrests, worn pale and glossy at their wrists. Beneath the couch was a woven wool rug, sand-colored and striped with black, that always shocked me if I dragged my feet across it. And everywhere -- sitting on window sills, resting atop the antique piano, hanging on the cream-colored walls -- were photographs of family, the three generations of Nietos and Gutierrezes who'd lived in the same house.

"Paupiette?" Rosa called out around a toothbrush, above the sound of water running in the bathroom sink.

"Little cup," I said, without missing a beat. To show off, I added, "As in hollowed-out cucumber filled with salmon mousse."

"Papillote?" she asked, trying to trick me with a term that sounded similar.

"Package," I said smugly. "As in fish steamed in a paper wrapper."

"Braggadocio," she said, and I'd begun to translate the term into something edible when it hit me it meant: smart aleck. The word had appeared on the SATs.

"Muchas gracias," I said.

I made my way down the hall slowly, admiring the series of silver-framed photos arranged in a line on the wall like a film strip. First, a view of the small orange grove the Nieto family had owned at Thirty-fifth Street, land that looked in 1930 like the end of the world. Then, pictures Rosa's grandfather Eduardo had taken, each a year apart, from the roof of the family's stucco-covered house. The photos showed the city creeping closer and closer, bringing houses and malls and ritzy mountain spas. Finally, they'd sold the orchard, bought a downtown storefront, and moved to the edge of a fancy neighborhood called Encanto Park.

Eventually, Rosa's mother married and brought her husband, Elias Gutierrez, home; that's where Rosa and her sister Christina were born. Nowadays, the neighbors enlivened their bungalows and Spanish colonials with turquoise and raspberry paint, but the Gutierrezes' house remained traditional mission white.

There was a photo of the whole family in front of the house: grandfather Eduardo, Donna and Elias, aunts and uncles and cousins up from Tucson, Christina and Tina's husband Tony, grandmother Nieto holding her namesake, baby Isabel. Behind them, the sagging arms of an old saguaro were draped with colored lights, and a sunburned plastic Santa stood guard by the door. The photo had been taken last Christmas, just before Dad's arrest.

Rosa came around the corner in her candy striper's uniform, twisting a tail of her long, mink-colored hair into a purple satin band. "I thought I'd find you here," she said, coming to stand beside me. I knew her family so well, had often wished they were my own.

I was looking at a photo of Tina's fifteenth birthday party, the quinceañara that Rosa had refused. In it, Tina wore a pink dress with a white sash and stood on the steps of St. Mary's, where her parents had once had to worship in the basement with others of Mexican descent. One of her white-gloved hands held a Bible, and the other shook the hand of the mayor, whose presence at the mass was recalled whenever the story was told.

Rosa had complained that the quinceañara was nonsense, more publicity for business than a celebration for her sister. Usually she scowled at the photo when she passed it, but today she blew dust off the cover glass and straightened the frame. Then she twirled in the peach aproned uniform she wore for her work at the hospital. "Here's my quinceañara dress," she said, laughing. "Much less expensive. Sweet, don't you think?"

"It's what all the candy stripers are wearing," I agreed.

"Ragout?" she quizzed me, wrapping an arm around my waist and pulling me to the front door.

"Gushy," I said, and winced as we stepped into the bright light outside.

"Gushy?" Rosa laughed, locking the door behind us. "I'd like to hear you say that to a customer."

"Whoops," I corrected myself. "I meant stewed."

* * * * *

"You should have seen the way he looked at me," I said, trying to rile Rosa about Kenny as we drove to The Phoenix. I wasn't testing Rosa so much as Kenny. I never knew what I could handle until Rosa checked it out.

But she wasn't having any of my complaints about Franklin's. "At least you're not cocktailing," she said, as she pretended to tune the awful AM radio and fussed with the inoperable air conditioning vent. "It's just one summer, Jaime. You'll be pouring tea for your calculus professor soon enough."

"And you'll be skipping class every time the surf's up," I kidded back. Rosa ignored me, pretending to be busy applying red lipstick in the sun visor mirror. "You missed the turn,"she said.

"It's at forty-eighth," I said.

"That was forty-eighth."

"Where's the church?" I asked, pulling into the left lane to make a U. "Wasn't there a church on that corner last week?"

"It's condos now," said Rosa.

Phoenix was disorienting that way; people and houses and businesses came and went so quickly, making a familiar landscape strange. Turning, I said, "It's a wonder the mountains don't get up and move."

Ahead, Camelback Mountain had always marked East and, for me, a new start. I would cross those mountains in August, I remembered with a rush of relief. Secretly I hoped that, when I came home for Christmas, Dad's trial would be over and his criminal record erased.

"Is this your uniform?" Rosa asked me, pulling the bell skirt from my backpack.

"I have to hem it five inches," I told her. "Practically to my navel."

"Five inches?" Rosa asked.

"That's the rule," I said.

Rosa unfurled the uniform and spread it across her lap. "Here's what you do," she said. She scrunched up the material, so the skirt looked even skimpier on her long legs than it would have on mine. "Follow the rule for the first week. Don't sew it, but fix it with tape. Then, little by little, let down the hem."

"That'll never work," I said.

"By the time this Kenny notices, he'll be so impressed with your work that he won't even care." Rosa pretended to tear the hem out, faking a juicy ripping sound.

"What if showing leg is my work?"

"Make him put it in your job description."

"Rosa!"

"Then quit and take my job at La Piñata."

"Take your job?" I asked, as surprised by her suggestion as I was by how much the idea appealed to me. Easy money, happy family -- I would have gladly traded her place for mine. "But you're doing so well," I said. "Your mom told me the mail-order business is really taking off."

"Oh, yes," said Rosa sarcastically. "We'll make sure no tourist leaves without a beaded fringe vest or an ashtray shaped like Arizona!"

"What's up with you, Rosa?"

"Nothing," she said, but that word was just the cork. It turned out her supervisor at Saguaro had asked her to help run a peer sex ed program for "high-risk" teens, a more polite word for kids from poor or violent or drug-dealing neighborhoods. Rosa had said "yes" immediately. But just that morning, her mother had said "no."

"Maybe she's afraid you'll learn something," I tried to joke.

"íQué lástima! I'm not a child!"

"Maybe she doesn't like the neighborhood," I suggested.

"The barrio, that's right," Rosa said, rolling her eyes. She unlocked her limbs, and flailed her arms in the air. "They want to pretend such poverty doesn't exist!"

"Maybe," I said. "But probably they just miss you already." I glanced at the A.S.U. application that lay on the dashboard, wondering if my mother was feeling the same thing.

Rosa didn't answer, but as we drove on, I saw her face soften and her hands refold neatly in her lap. It was the peacekeeping posture she'd put on for her parents ever since the letter came from Stanford, beckoning their last child away.

As I turned into the driveway for The Phoenix, the A.S.U. application tumbled to the floor. I bent to retrieve it, trying not to swerve. What was Mom up to? Was she hatching a plan to keep me home until Dad's trial? I tossed the application into the back seat, convinced that the lie I'd told that morning was turning into truth.

From the Hardcover edition.