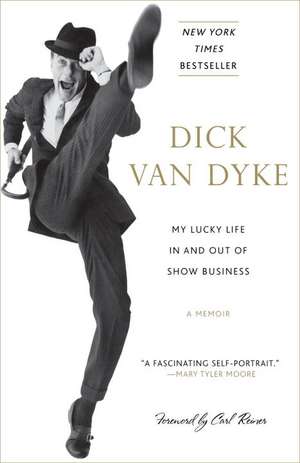

My Lucky Life in and Out of Show Business

Autor Dick van Dykeen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 apr 2012

His trailblazing television program, The Dick Van Dyke Show (produced by Carl Reiner, who has written the foreword to this memoir), was one of the most popular sitcoms of the 1960s and introduced another major television star, Mary Tyler Moore. But Dick Van Dyke was also an enormously engaging movie star whose films, including Mary Poppins and Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, have been discovered by a new generation of fans and are as beloved today as they were when they first appeared. Who doesn’t know the word supercalifragilisticexpialidocious?

A colorful, loving, richly detailed look at the decades of a multilayered life, My Lucky Life In and Out of Show Business, will enthrall every generation of reader, from baby-boomers who recall when Rob Petrie became a household name, to all those still enchanted by Bert’s “Chim Chim Cher-ee.” This is a lively, heartwarming memoir of a performer who still thinks of himself as a “simple song-and-dance man,” but who is, in every sense of the word, a classic entertainer.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 86.80 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 130

Preț estimativ în valută:

16.61€ • 17.24$ • 13.85£

16.61€ • 17.24$ • 13.85£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307592248

ISBN-10: 0307592243

Pagini: 287

Ilustrații: 2 8-PAGE 4-C INSERTS

Dimensiuni: 132 x 204 x 22 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

ISBN-10: 0307592243

Pagini: 287

Ilustrații: 2 8-PAGE 4-C INSERTS

Dimensiuni: 132 x 204 x 22 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

Notă biografică

DICK VAN DYKE was born in West Plains, Missouri, in 1925. He is an internationally recognized and accomplished performer, and has been a recipient of the Theatre World Award, a Tony, a Grammy, and four Emmy awards. He lives in California.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Chapter 1

STEP IN TIME

It was nighttime, February 1943, and I was standing next to my mother, thinking about the war in Europe. I had a very good relationship with my mother, so there's no need for any psychoanalysis about why I was thinking of the war. The fact was, we had finished dinner and she was washing the dishes and I was drying them, as was our routine. My father, a traveling salesman, was on the road, and my younger brother, Jerry, had run off to play.

We lived in Danville, Illinois, which was about as far away from the war as you could get. Danville was a small town in the heartland of America, and it felt very much like the heartland. It was quiet and neighborly, a place where there was a rich side of town and a poor side, but not a bad side. The streets were brick. The homes were built in the early 1900s. Everybody had a backyard; most were small but none had fences.

People left their doors open and their lights on, even when they went out. Occasionally someone down on their luck would knock on the back door and my mother would give him something to eat. Sometimes she would give him an odd job to do, too.

I had things on my mind that night. You could tell from the way I looked out the kitchen window as I did my part of the dishes. I stood six feet one inch and weighed 130 pounds, if that. I was a tall drink of water, as my grandmother said.

"I'm going to be eighteen in March," I said. "That means I'll be up for the draft. I really don't want to go-and I really don't want to be in the infantry. So I'm thinking that I ought to join now and try to get in the Air Force."

My mother let the dish she was washing slide back into the soapy water and dried her hands. She turned to me, a serious look on her face.

"I have something to tell you," she said.

"Yeah?"

"You're already eighteen," she said.

My jaw dropped. I was shocked.

"But how-"

"You were born a little premature," she explained. "You didn't have any fingernails. And there were a few other complications."

"Complications?" I said.

"Don't worry, you're fine now," she said, smiling. "But we just put your birth date forward to what would have been full term."

I wanted to know more than she was willing to reveal, so I turned to another source, my Grandmother Van Dyke. My grandparents on both sides lived nearby, but Grandmother Van Dyke was the most straightforward of the bunch. I stopped by her house one day after school and asked what she remembered about the complications that resulted from my premature birth.

She looked like she wanted to say "bullshit." She asked who had sold me a bill of goods.

"My mother," I replied.

"You weren't premature," she said.

"I wasn't?"

"You were conceived out of wedlock," she said, and then she went on to explain that my mother had gotten pregnant before she and my father married. Though it was never stated, I was probably the reason they got married. Eventually my mother confirmed the story, adding that after finding out, she and my father went to Missouri, where I was born. Then, following a certain amount of time, they returned to Danville.

It may not sound like such a big deal today, but back in 1925 it was the stuff of scandal. And eighteen years later, as I uncovered the facts, it was still pretty shocking to discover that I was a "love child."

I am still surprised the secret was kept from me for such a long time when others knew the truth. Danville was a town of thirty thousand people, and it felt as if most of them were relatives. I had a giant extended family. My great-grandparents on both sides were still alive, and I had first, second, and third cousins nearby. I could walk out of my house in any direction and hit a relative before I got tired.

There were good, industrious, upstanding, and attractive people in our family. There were no horse thieves or embezzlers. I was once given a family tree that showed the Van Dyke side was pretty unspectacular. My great-great-grandfather John Van Dyke went out west via the Donner Pass during the gold rush. After failing to find gold, he resettled in Green County, Pennsylvania.

The same family tree showed that Mother's side of the family, the McCords, could be traced back to Captain John Smith, who established the first English colony in Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607. Maybe it is true, but I never heard any talk about that when I was growing up. Nor have I fact-checked.

The part beyond dispute begins when my father, Loren, or L. W. Van Dyke, met my mother, Hazel McCord. She was a stenographer, and he was a minor-league baseball player: handsome, athletic, charming, the life of the party. And his talent did not end there. During the off-season, he played saxophone and clarinet in a jazz band. Although unable to read a note of music, he could play anything he heard.

He was enjoying the life of a carefree bon vivant until my mother informed him that she was in a family way. All of a sudden the good life as he knew it vanished. He accepted the responsibility, though, marrying my mom and getting a job as a salesman for the Sunshine Cookie Company.

He hated the work, but he always had a shine on his shoes and a smile on his face. Years later, when I saw Arthur Miller's play Death of a Salesman, I was depressed for a month. It was my dad's story.

He was saved by his sense of humor. Customers enjoyed his company when he dropped by. Known as Cookie, he was a good time wherever he went. Unfortunately for us, he was usually on the road all week and then spent weekends unwinding on the golf course or hunting with friends. At home, he would have a drink at night and smoke unfiltered Fatima cigarettes while talking to my mother.

He was more reserved around my brother and me, but we knew he loved us. We never questioned it. He was one of those men who did not know how to say the words. A joke was easy. At a party, everyone left talking about what a great guy he was. But a heart-to-heart talk with us boys was not in his repertoire. Years later, after I was married, Jerry and my dad drove to Atlanta to visit us. I asked Jerry what he and Dad had talked about on the drive. He shrugged his shoulders.

"You know Dad," he said. "Not much of anything."

My mother was the opposite. She was funny like my dad, but much more talkative. If she had a deficiency, it was a tendency toward absentmindedness. She once cooked a ham and later found it in my father's shirt drawer. I am not kidding. And when I was in my thirties, she confessed that when I was little she and my father would go to the movies and leave me at home by myself in the crib. I would be a mess when they returned.

"I don't know how I could've done that," she said.

"Me neither," I replied.

"But we were young," she said, smiling. "We didn't mean any harm. We just didn't know any better."

I was five and a half years old when my brother, Jerry, was born. It was not long before my parents moved him from a little bassinet in their room to a crib in my room and made it my job to go upstairs after dinner and gently shake the crib until he went to sleep. Within a year or two, I was given the job of babysitting. It wasn't a problem during the daytime when my mom ran errands and was gone a short time, but there were longer stretches at night when my parents went out and our old house filled with strange noises and eerie creaks, and I turned into a wreck.

Convinced that the place was haunted, I would pull a crate into the middle of the house and sit on it with an ax in my lap, ever vigilant and ready to protect my baby brother-and myself!

At six years old, I was sent to kindergarten. There was only one kindergarten in town, and it was located in the well-to-do section. The school was quite hoity-toity. Every morning my mother dressed me up and gave me two nickels. I used one for the six-mile trolley ride to Edison Elementary, and in the afternoon I used my other nickel to get back home.

For first grade, I switched to Franklin Elementary, which was on the other side of town, the side that was struggling even more than we were through the Great Depression. We didn't have much, but the families in this area did not have anything. All the boys at school wore overalls and work shoes-all of them except for me. I arrived on the first day in a Lord Fauntleroy suit, blue with a Peter Pan collar and a beret.

Since I was the only one in class with any schooling, the teacher made me the class monitor and assigned me to escort kids to the bathroom and back. It was a rough job. Some of the kids were crying. Others wanted to go home. I had my hands full all morning. Between my outfit and my job as helper, I was teased for being the teacher's pet.

At recess, I walked outside and a tough kid in overalls-his name was Al-punched me in the chest while another boy kneeled down behind me. Then Al pushed me backward, and I lost my balance and fell down. I ended up with a bloody nose and a few scratches. They also threw my beret on the roof, and for all I know, it is still there.

I was a mess when I got home after school.

"What in God's name happened to you?" my mother said.

I was too much of a little man to rat out the other kids.

I spared her the details and simply said, "Mom, I need some overalls."

As for the Depression, I remember my parents having some heated arguments about unpaid bills, and which bills to pay. They went in and out of debt and periodically got a second mortgage on the furniture. I wasn't aware of any hardship and never felt the stigma of having to watch every nickel. Everybody was poor.

Actually, we had it better than most. My maternal grandfather owned a grocery store that also sold kosher meat. He did well. He also owned our house, so we had free rent and food. My other grandfather worked in the shop at the East Illinois Railroad. The train yard was his life. He never took a vacation. If he had time off, he put up storm windows for one of us or fixed a broken door for someone. He was always busy.

On Christmas, we came downstairs in the morning and found him waiting for us, after having lit the tree, started a fire in the fireplace, and gotten everything ready. I looked up to him and, with my father on the road more often than not, he became a role model. He was a seemingly simple, industrious man, but he did a lot of thinking about things, too, and that rubbed off on me.

Thanks to my mother and her mother, there was a good measure of talk about religion in our house when I was growing up. Every summer, I went to Bible school. A bus picked me up across the street from our house early in the morning and brought me back in the afternoon. I hated it. I would rather have played and run around with friends.

Nonetheless, at age eleven, I took it upon myself to read the Bible from front to back. I struggled through the various books, asked questions, and when I reached the end I had no idea what any of it meant. But it pleased my mother and grandmother, who were proud of me and boasted to friends of my accomplishment.

As for my studies in school, I was a solid student. I was strong in English and Latin, but I got lost anytime the subject included math. I wish I had paid more attention to biology and science in general, subjects that came to interest me as an adult. I could have gotten better marks, but I never took a book home, never did homework. Come to think of it, neither of my parents ever looked at any of my report cards. They thought I was a good kid-and looking back, I guess I was.

Chapter 2

THE YAWN PATROL

Just before I started ninth grade, my father was transferred to Indiana and we spent a year in Crawfordsville. We took an apartment there. I came into my own. It was not a personality change as much as it was the realization that I had a personality. I also found out that I could run and jump pretty well, and I got on the freshman track team. Success on the track added to my self-confidence, including one particular day that still stands out as the most exciting of my life.

We lived across the street from Wabash College, a beautiful little school that gave the town a youthful feel. On Saturdays they hosted collegiate track meets, which our high-school coach helped officiate. I watched all the competitions. This one particular day, Wabash was running against Purdue University and I was in the stands when my coach came up to me and said that the anchorman on the Wabash team had turned his ankle and was unable to run in the race

"Do you want to run anchor?" he said.

"Are you kidding?" I replied.

"They need a man," he said.

What an offer! I was only fifteen years old, but heck, the chance to compete against college boys was one I did not want to pass up. Even though I didn't have track shoes, which were considered essential to running a good race, since in those days the tracks were layered with cinders, I jumped to my feet. Yes, I told my coach, I was ready to fill in for the Wabash team-and as anchor no less.

When I took the baton, Purdue's anchor was slightly ahead of me. I was not intimidated. We had one hundred yards ahead of us and he did not look that fast to me. I ran hard, gained ground every few steps, and passed him on the outside, with about twenty yards to go.

I heard the crowd roar and held on to the lead, crossing the tape before all the other college boys.

I won.

A high-school freshman.

Amazing.

They gave me a blue ribbon, which I took home and showed my father. He didn't believe me when I said I beat a college boy from Purdue. He thought I was lying. It was, I agreed, pretty far-fetched. The kid I beat was older and could really run. But I was faster-at least that day.

From the Hardcover edition.

STEP IN TIME

It was nighttime, February 1943, and I was standing next to my mother, thinking about the war in Europe. I had a very good relationship with my mother, so there's no need for any psychoanalysis about why I was thinking of the war. The fact was, we had finished dinner and she was washing the dishes and I was drying them, as was our routine. My father, a traveling salesman, was on the road, and my younger brother, Jerry, had run off to play.

We lived in Danville, Illinois, which was about as far away from the war as you could get. Danville was a small town in the heartland of America, and it felt very much like the heartland. It was quiet and neighborly, a place where there was a rich side of town and a poor side, but not a bad side. The streets were brick. The homes were built in the early 1900s. Everybody had a backyard; most were small but none had fences.

People left their doors open and their lights on, even when they went out. Occasionally someone down on their luck would knock on the back door and my mother would give him something to eat. Sometimes she would give him an odd job to do, too.

I had things on my mind that night. You could tell from the way I looked out the kitchen window as I did my part of the dishes. I stood six feet one inch and weighed 130 pounds, if that. I was a tall drink of water, as my grandmother said.

"I'm going to be eighteen in March," I said. "That means I'll be up for the draft. I really don't want to go-and I really don't want to be in the infantry. So I'm thinking that I ought to join now and try to get in the Air Force."

My mother let the dish she was washing slide back into the soapy water and dried her hands. She turned to me, a serious look on her face.

"I have something to tell you," she said.

"Yeah?"

"You're already eighteen," she said.

My jaw dropped. I was shocked.

"But how-"

"You were born a little premature," she explained. "You didn't have any fingernails. And there were a few other complications."

"Complications?" I said.

"Don't worry, you're fine now," she said, smiling. "But we just put your birth date forward to what would have been full term."

I wanted to know more than she was willing to reveal, so I turned to another source, my Grandmother Van Dyke. My grandparents on both sides lived nearby, but Grandmother Van Dyke was the most straightforward of the bunch. I stopped by her house one day after school and asked what she remembered about the complications that resulted from my premature birth.

She looked like she wanted to say "bullshit." She asked who had sold me a bill of goods.

"My mother," I replied.

"You weren't premature," she said.

"I wasn't?"

"You were conceived out of wedlock," she said, and then she went on to explain that my mother had gotten pregnant before she and my father married. Though it was never stated, I was probably the reason they got married. Eventually my mother confirmed the story, adding that after finding out, she and my father went to Missouri, where I was born. Then, following a certain amount of time, they returned to Danville.

It may not sound like such a big deal today, but back in 1925 it was the stuff of scandal. And eighteen years later, as I uncovered the facts, it was still pretty shocking to discover that I was a "love child."

I am still surprised the secret was kept from me for such a long time when others knew the truth. Danville was a town of thirty thousand people, and it felt as if most of them were relatives. I had a giant extended family. My great-grandparents on both sides were still alive, and I had first, second, and third cousins nearby. I could walk out of my house in any direction and hit a relative before I got tired.

There were good, industrious, upstanding, and attractive people in our family. There were no horse thieves or embezzlers. I was once given a family tree that showed the Van Dyke side was pretty unspectacular. My great-great-grandfather John Van Dyke went out west via the Donner Pass during the gold rush. After failing to find gold, he resettled in Green County, Pennsylvania.

The same family tree showed that Mother's side of the family, the McCords, could be traced back to Captain John Smith, who established the first English colony in Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607. Maybe it is true, but I never heard any talk about that when I was growing up. Nor have I fact-checked.

The part beyond dispute begins when my father, Loren, or L. W. Van Dyke, met my mother, Hazel McCord. She was a stenographer, and he was a minor-league baseball player: handsome, athletic, charming, the life of the party. And his talent did not end there. During the off-season, he played saxophone and clarinet in a jazz band. Although unable to read a note of music, he could play anything he heard.

He was enjoying the life of a carefree bon vivant until my mother informed him that she was in a family way. All of a sudden the good life as he knew it vanished. He accepted the responsibility, though, marrying my mom and getting a job as a salesman for the Sunshine Cookie Company.

He hated the work, but he always had a shine on his shoes and a smile on his face. Years later, when I saw Arthur Miller's play Death of a Salesman, I was depressed for a month. It was my dad's story.

He was saved by his sense of humor. Customers enjoyed his company when he dropped by. Known as Cookie, he was a good time wherever he went. Unfortunately for us, he was usually on the road all week and then spent weekends unwinding on the golf course or hunting with friends. At home, he would have a drink at night and smoke unfiltered Fatima cigarettes while talking to my mother.

He was more reserved around my brother and me, but we knew he loved us. We never questioned it. He was one of those men who did not know how to say the words. A joke was easy. At a party, everyone left talking about what a great guy he was. But a heart-to-heart talk with us boys was not in his repertoire. Years later, after I was married, Jerry and my dad drove to Atlanta to visit us. I asked Jerry what he and Dad had talked about on the drive. He shrugged his shoulders.

"You know Dad," he said. "Not much of anything."

My mother was the opposite. She was funny like my dad, but much more talkative. If she had a deficiency, it was a tendency toward absentmindedness. She once cooked a ham and later found it in my father's shirt drawer. I am not kidding. And when I was in my thirties, she confessed that when I was little she and my father would go to the movies and leave me at home by myself in the crib. I would be a mess when they returned.

"I don't know how I could've done that," she said.

"Me neither," I replied.

"But we were young," she said, smiling. "We didn't mean any harm. We just didn't know any better."

I was five and a half years old when my brother, Jerry, was born. It was not long before my parents moved him from a little bassinet in their room to a crib in my room and made it my job to go upstairs after dinner and gently shake the crib until he went to sleep. Within a year or two, I was given the job of babysitting. It wasn't a problem during the daytime when my mom ran errands and was gone a short time, but there were longer stretches at night when my parents went out and our old house filled with strange noises and eerie creaks, and I turned into a wreck.

Convinced that the place was haunted, I would pull a crate into the middle of the house and sit on it with an ax in my lap, ever vigilant and ready to protect my baby brother-and myself!

At six years old, I was sent to kindergarten. There was only one kindergarten in town, and it was located in the well-to-do section. The school was quite hoity-toity. Every morning my mother dressed me up and gave me two nickels. I used one for the six-mile trolley ride to Edison Elementary, and in the afternoon I used my other nickel to get back home.

For first grade, I switched to Franklin Elementary, which was on the other side of town, the side that was struggling even more than we were through the Great Depression. We didn't have much, but the families in this area did not have anything. All the boys at school wore overalls and work shoes-all of them except for me. I arrived on the first day in a Lord Fauntleroy suit, blue with a Peter Pan collar and a beret.

Since I was the only one in class with any schooling, the teacher made me the class monitor and assigned me to escort kids to the bathroom and back. It was a rough job. Some of the kids were crying. Others wanted to go home. I had my hands full all morning. Between my outfit and my job as helper, I was teased for being the teacher's pet.

At recess, I walked outside and a tough kid in overalls-his name was Al-punched me in the chest while another boy kneeled down behind me. Then Al pushed me backward, and I lost my balance and fell down. I ended up with a bloody nose and a few scratches. They also threw my beret on the roof, and for all I know, it is still there.

I was a mess when I got home after school.

"What in God's name happened to you?" my mother said.

I was too much of a little man to rat out the other kids.

I spared her the details and simply said, "Mom, I need some overalls."

As for the Depression, I remember my parents having some heated arguments about unpaid bills, and which bills to pay. They went in and out of debt and periodically got a second mortgage on the furniture. I wasn't aware of any hardship and never felt the stigma of having to watch every nickel. Everybody was poor.

Actually, we had it better than most. My maternal grandfather owned a grocery store that also sold kosher meat. He did well. He also owned our house, so we had free rent and food. My other grandfather worked in the shop at the East Illinois Railroad. The train yard was his life. He never took a vacation. If he had time off, he put up storm windows for one of us or fixed a broken door for someone. He was always busy.

On Christmas, we came downstairs in the morning and found him waiting for us, after having lit the tree, started a fire in the fireplace, and gotten everything ready. I looked up to him and, with my father on the road more often than not, he became a role model. He was a seemingly simple, industrious man, but he did a lot of thinking about things, too, and that rubbed off on me.

Thanks to my mother and her mother, there was a good measure of talk about religion in our house when I was growing up. Every summer, I went to Bible school. A bus picked me up across the street from our house early in the morning and brought me back in the afternoon. I hated it. I would rather have played and run around with friends.

Nonetheless, at age eleven, I took it upon myself to read the Bible from front to back. I struggled through the various books, asked questions, and when I reached the end I had no idea what any of it meant. But it pleased my mother and grandmother, who were proud of me and boasted to friends of my accomplishment.

As for my studies in school, I was a solid student. I was strong in English and Latin, but I got lost anytime the subject included math. I wish I had paid more attention to biology and science in general, subjects that came to interest me as an adult. I could have gotten better marks, but I never took a book home, never did homework. Come to think of it, neither of my parents ever looked at any of my report cards. They thought I was a good kid-and looking back, I guess I was.

Chapter 2

THE YAWN PATROL

Just before I started ninth grade, my father was transferred to Indiana and we spent a year in Crawfordsville. We took an apartment there. I came into my own. It was not a personality change as much as it was the realization that I had a personality. I also found out that I could run and jump pretty well, and I got on the freshman track team. Success on the track added to my self-confidence, including one particular day that still stands out as the most exciting of my life.

We lived across the street from Wabash College, a beautiful little school that gave the town a youthful feel. On Saturdays they hosted collegiate track meets, which our high-school coach helped officiate. I watched all the competitions. This one particular day, Wabash was running against Purdue University and I was in the stands when my coach came up to me and said that the anchorman on the Wabash team had turned his ankle and was unable to run in the race

"Do you want to run anchor?" he said.

"Are you kidding?" I replied.

"They need a man," he said.

What an offer! I was only fifteen years old, but heck, the chance to compete against college boys was one I did not want to pass up. Even though I didn't have track shoes, which were considered essential to running a good race, since in those days the tracks were layered with cinders, I jumped to my feet. Yes, I told my coach, I was ready to fill in for the Wabash team-and as anchor no less.

When I took the baton, Purdue's anchor was slightly ahead of me. I was not intimidated. We had one hundred yards ahead of us and he did not look that fast to me. I ran hard, gained ground every few steps, and passed him on the outside, with about twenty yards to go.

I heard the crowd roar and held on to the lead, crossing the tape before all the other college boys.

I won.

A high-school freshman.

Amazing.

They gave me a blue ribbon, which I took home and showed my father. He didn't believe me when I said I beat a college boy from Purdue. He thought I was lying. It was, I agreed, pretty far-fetched. The kid I beat was older and could really run. But I was faster-at least that day.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“In my opinion, ‘Luck’ has little to do with Dick Van Dyke’s life. It is, rather, his innate kindness and talent that have had an extraordinary effect in shaping the man. And what a fascinating self-portrait he’s given us in this book.”

—Mary Tyler Moore

“From the time I worked with Dick on the movie Bye Bye Birdie, I have admired his many talents, not the least of which is the joy and enthusiasm he shares with audiences. I’m a big fan of his……and his book.”—Ann-Margret

“Van Dyke tells a wonderful story about himself and his times. And—in an often surprsingly relevant manner—our times. We’ve always liked the performer—it’s hard not to like Dick Van Dyke—but this will will make you admire him.”--Playbill

From the Hardcover edition.

—Mary Tyler Moore

“From the time I worked with Dick on the movie Bye Bye Birdie, I have admired his many talents, not the least of which is the joy and enthusiasm he shares with audiences. I’m a big fan of his……and his book.”—Ann-Margret

“Van Dyke tells a wonderful story about himself and his times. And—in an often surprsingly relevant manner—our times. We’ve always liked the performer—it’s hard not to like Dick Van Dyke—but this will will make you admire him.”--Playbill

From the Hardcover edition.

Descriere

The "New York Times"-bestselling memoir by one of the greatest, world-class entertainers of his generation, as beloved for "The Dick Van Dyke Show" as for his roles in movies such as "Mary Poppins."